Petitioners, Respondents. AMICUS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Courses, Fall 2019

ENGLISH COURSES, FALL 2019 ENGL 102-012 English Composition II: The Gothic in Literature and Film Dr. Williams TTH 6:00-7:15 Course Description: Engl. 102 belongs to the composition requirement in the English department. However, reading good literature and watching challenging film versions is often as beneficial as taking a strictly grammatical approach and this will be the aim of the particular class offered. With reference to H.P. Lovecraft's essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature", the class will examine various aspects of the Gothic associated with the work of Edgar Allan Poe and Hammer studios. Beginning with readings from "The Fall of the House of Usher," The Pit and the Pendulum", and other works also available from youtube and public domain, the class will study visual depictions of the Gothic in the 1960s Poe/Roger Corman cycles. Following the Mercury Theatre 1938 production of DRACULA by Orson welles, the class will examine how Hammer Studios reproduced the Gothic in the late 50s and 60s with screenings of THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN, THE REVENGE OF FRANKENSTEIN, THE HORROR OF DRACULA, DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA, and DR. JEKYLL AND SISTER HYDE. All written material will be accessible from Project Gutenberg under public domain. Requirements: Five written assignments (five page minimum). ENGL 119-004 Intro to Creative Writing Professor Jordan TTH 2:00-3:15 In this introduction to creative writing course, students will concentrate on two genres—poetry and fiction. We will read contemporary poems and stories paying especial attention to the writers’ strategies for imparting information and learning how to use that craft in our own writing. -

MCOM 419: Popular Culture and Mass Communication Spring 2016 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9-10:15 A.M., UC323

MCOM 419: Popular Culture and Mass Communication Spring 2016 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9-10:15 a.m., UC323. Professor Drew Morton E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday, 10-12 p.m., UC228 COURSE DESCRIPTION AND STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: This course focuses on the theories of media studies that have broadened the scope of the field in the past thirty years. Topics and authors include: comics studies (Scott McCloud), fan culture (Henry Jenkins), gender (Lynn Spigel), new media (Lev Manovich), race (Aniko Bodrogkozy, Herman Gray), and television (John Caldwell, Raymond Williams). Before the conclusion of this course, students should be able to: 1. Exhibit an understanding of the cultural developments that have driven the evolution of American comics (mastery will be assessed by the objective midterm and short response papers). 2. Exhibit an understanding of the industrial structures that have defined the history of American comics (mastery will be assessed by the objective midterm). 3. Exhibit an understanding of the terminology and theories that help us analyze American comics as a cultural artifact and as a work of art (mastery will be assessed by classroom participation and short response papers). REQUIRED TEXTS/MATERIALS: McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (William Morrow, 1994). Moore, Alan. Watchmen (DC Comics, 2014). Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art (Phaidon, 2001). Spiegelman, Art. Maus I and II: A Survivor’s Tale (Pantheon, 1986 and 1992). Additional readings will be distributed via photocopy, PDF, or e-mail. Students will also need to have Netflix, Hulu, and/or Amazon to stream certain video titles on their own. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

GRAPHIC NOVELS in ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: a PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater a Dissertation Submi

GRAPHIC NOVELS IN ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Madeleine Grumet James Trier Jeff Greene Lucila Vargas Renee Hobbs © 2012 Cary Gillenwater ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CARY GILLENWATER: Graphic novels in advanced English/language arts classrooms: A phenomenological case study (Under the direction of Madeleine Grumet) This dissertation is a phenomenological case study of two 12th grade English/language arts (ELA) classrooms where teachers used graphic novels with their advanced students. The primary purpose of this case study was to gain insight into the phenomenon of using graphic novels with these students—a research area that is currently limited. Literature from a variety of disciplines was compared and contrasted with observations, interviews, questionnaires, and structured think-aloud activities for this purpose. The following questions guided the study: (1) What are the prevailing attitudes/opinions held by the ELA teachers who use graphic novels and their students about this medium? (2) What interests do the students have that connect to the phenomenon of comic book/graphic novel reading? (3) How do the teachers and the students make meaning from graphic novels? The findings generally affirmed previous scholarship that the medium of comic books/graphic novels can play a beneficial role in ELA classrooms, encouraging student involvement and ownership of texts and their visual literacy development. The findings also confirmed, however, that teachers must first conceive of literacy as more than just reading and writing phonetic texts if the use of the medium is to be more than just secondary to traditional literacy. -

Dissertation M.C. Cissell December 2016

ARC OF THE ABSENT AUTHOR: THOMAS PYNCHON’S TRAJECTORY FROM ENTROPY TO GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English and German Philology In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of English Philology Matthew Clayton Cissell December 2016 Director: María Felisa López Liquete Co-director: Ángel Chaparro Sainz (c)2017 MATTHEW CLAYTON CISSELL Abstract The central thesis of this dissertation is that Thomas Pynchon has come to occupy a specific position in the field of literature and that this can be seen in his latest novel, Against the Day , in which he is not so much writing about the past or even the present, but about what the present can become, about where it might be driven. Pynchon is self-consciously exploring the politics in the discursive field in which his book is situated, using the fin-de-siècle to highlight the ways that the present is geared toward catastrophe and that people, in a dans macabre , hurl themselves toward that endgame. The theoretical view and methodology behind my analysis of the novel draws to a great extent on the work of Pierre Bourdieu, specifically his sociological literary analysis. This sets an academic precedent in studies of Pynchon’s novels but it also requires applying an approach that has several necessary and onerous steps. In order to see how the social space of the novel is a refracted image of the author’s own social world one must analyse the field of power, after that the literary field and the positions of agents, next the space of possibilities, all of which help one understand the genesis of the author’s habitus and thus his trajectory and the creative project that develops. -

Primary Sources

1 Works Cited Primary Sources "Code of the Comics Magazine Association Inc." Comics Magazine Association Inc., www.visitthecapitol.gov/exhibitions/artifact/code-comics-magazine-association-america- inc-1954. Accessed 20 Oct. 2019. This website contains photo slides which provided me with pictures of the Comics Code Authority pamphlet (the barrier itself), the senate hearings, and copies of the two letters written by Robert Meridian (the child) and Eugenia Y. Genovar (the parent). I was able to deepen my understanding about the range of perspectives taking a hand in this conversation, therefore adding complexity to the topic itself. Crotty, Rob. "The Congressional Archives NARA Unit Preserves History of Legislation in the House, Senate." The Congressional Archives NARA Unit Preserves History of Legislation in House, Senate, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 2009, www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2009/fall/congressional.html. Accessed 15 Oct. 2019. This is a website which contains photographs from the Subcommittee of Juvenile Delinquency. This was used in the Senate Hearings tab, and provided details to how this testimony was “the nail to the coffin”\s his testimony provoked the committee to justify their suspicions and overall view on the subject matter, to recommend censorship on comic books. 2 “Eisenhower and McCarthy.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/eisenhower-politics/.. This website provided a photograph of Joseph Mccarthy, so readers can tie a face to the name repeated throughout the tab of Mccarthyism and the Second Red Scare “Grand Comics Database.” Grand Comics Database, Grand Comics Database, www.comics.org/. This was a database that provided all of the comic book covers in the website. -

VICTOR FOX? STARRING: EISNER • IGER BAKER • FINE • SIMON • KIRBY TUSKA • HANKS • BLUM Et Al

Roy Tho mas ’ Foxy $ Comics Fan zine 7.95 No.101 In the USA May 2011 WHO’S AFRAID OF VICTOR FOX? STARRING: EISNER • IGER BAKER • FINE • SIMON • KIRBY TUSKA • HANKS • BLUM et al. EXTRA!! 05 THE GOLDEN AGE OF 1 82658 27763 5 JACK MENDELLSOHN [Phantom Lady & Blue Beetle TM & ©2011 DC Comics; other art ©2011 Dave Williams.] Vol. 3, No. 101 / May 2011 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll OW WITH Jerry G. Bails (founder) N Ronn Foss, Biljo White 16 PAGES Mike Friedrich LOR! Proofreader OF CO Rob Smentek Cover Artist David Williams Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko Writer/Editorial – A Fanzine Is As A Fanzine Does . 2 With Special Thanks to: Rob Allen Allan Holtz/ The Education Of Victor Fox . 3 Heidi Amash “Stripper’s Guide” Richard Kyle’s acclaimed 1962 look at Fox Comics—and some reasons why it’s still relevant! Bob Andelman Sean Howe Henry Andrews Bob Hughes Superman Vs. The Wonder Man 1939 . 27 Ken Quattro presents—and analyzes—the testimony in the first super-hero comics trial ever. Ger Apeldoorn Greg Huneryager Jim Beard Paul Karasik “Cartooning Was Ultimately My Goal” . 59 Robert Beerbohm Denis Kitchen Jim Amash commences a candid conversation with Golden Age writer/artist Jack Mendelsohn. John Benson Richard Kyle Dominic Bongo Susan Liberator Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! The Mystery Of Bill Bossert & Ulla Edgar Loftin The Missing Letterer . 69 Neigenfind-Bossert Jim Ludwig Michael T. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Welcome to Online Office Hours!

Welcome to Online Office Hours! We’ll get started at 2PM ET Library of Congress Online Office Hours Welcome! We’re glad you’re here! Use the chat box to introduce yourselves. Let us know: Your first name Where you’re joining us from Grade level(s) and subject(s) you teach “Challenges to the Comics Code Authority” and a Glimpse into the Library’s Comic Arts Collection Martha Kennedy Curator of Popular & Applied Graphic Art, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Richard D. Deverell PhD Candidate, Department of History, SUNY Buffalo Library of Congress Swann Foundation Fellow, 2019-2020 Brought to you by the Library’s Learning and Innovation Office and the Library’s Prints & Photographs Division in collaboration with the Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon Comic Arts Collections at the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division holds multiple collections of original art for comics within its holdings of an estimated 129,000 original cartoon drawings and prints, including: • Swann Collection of Caricature and Cartoon • 400+ records for comic strips; 20+ comic book page drawings • Cartoon Drawings • 400+ records for comic strips; 50+ records for comic book page drawings • Wood Collection of Cartoon and Caricature Drawings • 200+ digitized comic strips to date Serials & Government Publications Division holds the largest publicly accessible collection of comic books in the United States: over 12,000 titles in all, totaling more than 140,000 issues. (Completing a Comic Book Request form is required for use of the collection.) From “Comic Art” Exhibition press release, 2019 Related Resources on the Library’s Website Selected Library of Congress exhibitions online that feature comics: • Comic Art: 120 Years of Panels and Pages • Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists • Cartoon America [Selections from the Art Wood Collection] Other Library of Congress freely accessible digital collections containing comics: • Webcomics Web Archive • Focuses specifically on comics created for the web. -

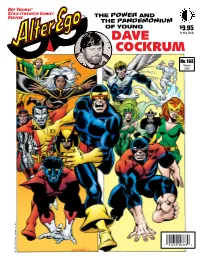

Dave Cockrum Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: the Red Planet—Mostly in Black-&-White!

Roy Thomas' Xtra-strength Comics Fanzine THE POWER AND THE PANDEMONIUM OF YOUNG $9.95 DAVE In the USA COCKRUM No. 163 March 2020 1 82658 00376 0 Art TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 163 / March 2020 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editor Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Don’t STEAL our J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Digital Editions! C’mon citizen, Comic Crypt Editor DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom Michael T. Gilbert & Pop publisher like us needs Editorial Honor Roll every sale just to survive! DON’T Jerry G. Bails (founder) DOWNLOAD Ronn Foss, Biljo White OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Mike Friedrich, Bill Schelly Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com Proofreaders or through our Apple and Google Apps! Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep Cover Artist producing great publications like this one! Dave Cockrum Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: The Red Planet—Mostly In Black-&-White! .. 2 Glenn Whitmore The Genius of Dave & Paty Cockrum .................. 3 With Special Thanks to: Joe Kramar’s 2003 conversation with one of comics’ most amazing couples. Don Allen David Hajdu Paul Allen Heritage Comics Dave Cockrum—A Model Artist....................... 11 Heidi Amash Auctions Andy Yanchus take a personal look back at his friend’s astonishing model work. Pedro Angosto Tony Isabella “One Of The Most Celebrated Richard Arndt Eric Jansen Bob Bailey Sharon Karibian Comicbook Artists Of Our Time” .................... 15 Mike W. Barr Jim Kealy Paul Allen on corresponding with young Dave Cockrum, ERB fan, in 1969-70. -

Innovators: Songwriters

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: SONGWRITERS David Galenson Working Paper 15511 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15511 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2009 The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by David Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Songwriters David Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15511 November 2009 JEL No. N00 ABSTRACT Irving Berlin and Cole Porter were two of the great experimental songwriters of the Golden Era. They aimed to create songs that were clear and universal. Their ability to do this improved throughout much of their careers, as their skill in using language to create simple and poignant images improved with experience, and their greatest achievements came in their 40s and 50s. During the 1960s, Bob Dylan and the team of John Lennon and Paul McCartney created a conceptual revolution in popular music. Their goal was to express their own ideas and emotions in novel ways. Their creativity declined with age, as increasing experience produced habits of thought that destroyed their ability to formulate radical new departures from existing practices, so their most innovative contributions appeared early in their careers. -

Comic Books, Dr. Wertham, and the Villains of Forensic Psychiatry

ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY Comic Books, Dr. Wertham, and the Villains of Forensic Psychiatry Ryan Chaloner Winton Hall, MD, and Susan Hatters Friedman, MD Comic books have been part of popular culture since the 1930s. Social activists quickly became con- cerned about the risk that comic books posed for youth, including that their content was a cause of juvenile delinquency. Dr. Fredric Wertham, a forensic psychiatrist, led efforts to protect society’s chil- dren from comic books, culminating in multiple publications, symposia, and testimony before a Senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency in 1954. During the course of his activities, and quite possibly as a backlash, comics started to represent psychiatrists and particularly forensic psychiatrists as evil, clue- less, and narcissistic characters (e.g., Dr. Hugo Strange went from being a mad scientist to a mad psychi- atrist). Clinical forensic psychiatrists who were not necessarily evil were often portrayed as inept regarding rehabilitation. There are very few positive portrayals of forensic psychiatrists in the comic book universe, and when they do occur, they often have severe character flaws or a checkered history. These negative characterizations are woven into the fabric of contemporary comic book characters, whether represented in comic books or other media offshoots such as films and television. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 48:536–44, 2020. DOI:10.29158/JAAPL.200041-20 Key words: comics; Fredric Wertham; forensic psychiatry; moral panic; popular culture; stigma Comic books in their current form came into exis- perceived harms of comic books was Dr. Fredric tence around 1935, with the superhero genre being Wertham.1–7 The intention of this article is to firmly established in 1939 with the introduction of a describe how Dr.