Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 'Women's Lib' Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

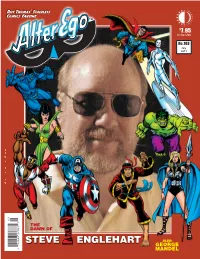

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

MCOM 419: Popular Culture and Mass Communication Spring 2016 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9-10:15 A.M., UC323

MCOM 419: Popular Culture and Mass Communication Spring 2016 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9-10:15 a.m., UC323. Professor Drew Morton E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday, 10-12 p.m., UC228 COURSE DESCRIPTION AND STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: This course focuses on the theories of media studies that have broadened the scope of the field in the past thirty years. Topics and authors include: comics studies (Scott McCloud), fan culture (Henry Jenkins), gender (Lynn Spigel), new media (Lev Manovich), race (Aniko Bodrogkozy, Herman Gray), and television (John Caldwell, Raymond Williams). Before the conclusion of this course, students should be able to: 1. Exhibit an understanding of the cultural developments that have driven the evolution of American comics (mastery will be assessed by the objective midterm and short response papers). 2. Exhibit an understanding of the industrial structures that have defined the history of American comics (mastery will be assessed by the objective midterm). 3. Exhibit an understanding of the terminology and theories that help us analyze American comics as a cultural artifact and as a work of art (mastery will be assessed by classroom participation and short response papers). REQUIRED TEXTS/MATERIALS: McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (William Morrow, 1994). Moore, Alan. Watchmen (DC Comics, 2014). Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art (Phaidon, 2001). Spiegelman, Art. Maus I and II: A Survivor’s Tale (Pantheon, 1986 and 1992). Additional readings will be distributed via photocopy, PDF, or e-mail. Students will also need to have Netflix, Hulu, and/or Amazon to stream certain video titles on their own. -

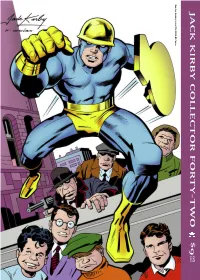

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Cvr a Andrea Sorrentino (Mr) $5.99 Aug21 7002 Batman the Imposter #1 (Of 3) Cvr B Lee Bermejo Var (Mr) $5.99

DC ENTERTAINMENT AUG21 7001 BATMAN THE IMPOSTER #1 (OF 3) CVR A ANDREA SORRENTINO (MR) $5.99 AUG21 7002 BATMAN THE IMPOSTER #1 (OF 3) CVR B LEE BERMEJO VAR (MR) $5.99 AUG21 7004 BATMAN #114 CVR A JORGE JIMENEZ (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7005 BATMAN #114 CVR B JORGE MOLINA CARD STORK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7007 BATMAN #115 CVR A JORGE JIMENEZ (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7008 BATMAN #115 CVR B JORGE MOLINA CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7010 ARKHAM CITY THE ORDER OF THE WORLD #1 (OF 6) CVR A SAM WOLFE CONNELLY $3.99 AUG21 7011 ARKHAM CITY THE ORDER OF THE WORLD #1 (OF 6) CVR B FRANCESCO MATTINA CARD STOCK VAR $4.99 AUG21 7013 BATMAN SECRET FILES PEACEKEEPER-01 #1 (ONE SHOT) CVR A RAFAEL SARMENTO (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7014 BATMAN SECRET FILES PEACEKEEPER-01 #1 (ONE SHOT) CVR B TYLER KIRKHAM CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7016 CATWOMAN #36 CVR A YANICK PAQUETTE (FEAR STATE) $3.99 AUG21 7017 CATWOMAN #36 CVR B JENNY FRISON CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7018 NIGHTWING #85 CVR A BRUNO REDONDO (FEAR STATE) $3.99 AUG21 7019 NIGHTWING #85 CVR B JAMAL CAMPBELL CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7020 DETECTIVE COMICS #1044 CVR A DAN MORA (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7021 DETECTIVE COMICS #1044 CVR B LEE BERMEJO CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7022 I AM BATMAN #2 CVR A OLIVIER COIPEL (FEAR STATE) $3.99 AUG21 7023 I AM BATMAN #2 CVR B FRANCESCO MATTINA CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7024 BATMAN URBAN LEGENDS #8 CVR A COLLEEN DORAN (FEAR STATE) $7.99 AUG21 7025 BATMAN URBAN LEGENDS #8 CVR B KHARY RANDOLPH -

The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh the Asian Conference on Arts

Diminished Power: The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most recognized characters that has become a part of the pantheon of pop- culture is Wonder Woman. Ever since she debuted in 1941, Wonder Woman has been established as one of the most familiar feminist icons today. However, one of the issues that this paper contends is that this her categorization as a feminist icon is incorrect. This question of her status is important when taking into account the recent position that Wonder Woman has taken in the DC Comics Universe. Ever since it had been decided to reset the status quo of the characters from DC Comics in 2011, the character has suffered the most from the changes made. No longer can Wonder Woman be seen as the same independent heroine as before, instead she has become diminished in status and stature thanks to the revamp on her character. This paper analyzes and discusses the diminishing power base of the character of Wonder Woman, shifting the dynamic of being a representative of feminism to essentially becoming a run-of-the-mill heroine. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org One of comics’ oldest and most enduring characters, Wonder Woman, celebrates her seventy fifth anniversary next year. She has been continuously published in comic book form for over seven decades, an achievement that can be shared with only a few other iconic heroes, such as Batman and Superman. Her greatest accomplishment though is becoming a part of the pop-culture collective consciousness and serving as a role model for the feminist movement. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung "60 Jahre Marvel

Liebe Kulturfreund*innen, bereits seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs befasst sich das Amerikahaus München mit US- amerikanischer Kultur. Als US-amerikanische Behörde war es zunächst für seine Bibliothek und seinen Lesesaal bekannt. Doch schon bald wurde das Programm des Amerikahauses durch Konzerte, Filmvorführungen und Vorträge ergänzt. Im Jahr 1957 zog das Amerika- haus in sein heutiges charakteristisches Gebäude ein und ist dort, nach einer vierjährigen Generalsanierung, seit letztem Jahr wieder zu finden. 2014 gründete sich die Stiftung Bay- erisches Amerikahaus, deren Träger der Freistaat Bayern ist. Heute bietet das Amerikahaus der Münchner Gesellschaft und über die Stadt- und Landesgrenzen hinaus ein vielfältiges Programm zu Themen rund um die transatlantischen Beziehungen – die Vereinigten Staaten, Kanada und Lateinamerika- und dem Schwerpunkt Demokratie an. Unsere einladenden Aus- stellungräume geben uns die Möglichkeit, Werke herausragender Künstler*innen zu zeigen. Mit dem Comicfestival München verbindet das Amerikahaus eine langjährige Partnerschaft. Wir freuen uns sehr, dass wir mit der Ausstellung „60 Jahre Marvel Comics Universe“ bereits die fünfte Ausstellung im Rahmen des Comicfestivals bei uns im Haus zeigen können. In der Vergangenheit haben wir mit unseren Ausstellungen einzelne Comickünstler, wie Tom Bunk, Robert Crumb oder Denis Kitchen gewürdigt. Vor zwei Jahren freute sich unser Publikum über die Ausstellung „80 Jahre Batman“. Dieses Jahr schließen wir mit einem weiteren Jubiläum an und feiern das 60-jährige Bestehen des Marvel-Verlags. Im Mainstream sind die Marvel- Helden durch die in den letzten Jahren immer beliebter gewordenen Blockbuster bekannt geworden, doch Spider-Man & Co. gab es schon lange davor. Das Comic-Heft „Fantastic Four #1“ gab vor 60 Jahren den Startschuss des legendären Marvel-Universums. -

Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women's Lib”

Wonder Woman Wears Pants: Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women’s Lib” Issue Ann Matsuuchi Envisioning the comic book superhero Wonder Woman as a feminist activist defending a women’s clinic from pro-life villains at first seems to be the kind of story found only in fan art, not in the pages of the canonical series itself. Such a radical character reworking did not seem so outlandish in the American cultural landscape of the early 1970s. What the word “woman” meant in ordinary life was undergoing unprecedented change. It is no surprise that the iconic image of a female superhero, physically and intellectually superior to the men she rescues and punishes, would be claimed by real-life activists like Gloria Steinem. In the following essay I will discuss the historical development of the character and relate it to her presentation during this pivotal era in second wave feminism. A six issue story culminating in a reproductive rights battle waged by Wonder Woman- as-ordinary-woman-in-pants was unfortunately never realised and has remained largely forgotten due to conflicting accounts and the tangled politics of the publishing world. The following account of the only published issue of this story arc, the 1972 Women’s Lib issue of Wonder Woman, will demonstrate how looking at mainstream comic books directly has much to recommend it to readers interested in popular representations of gender and feminism. Wonder Woman is an iconic comic book superhero, first created not as a female counterpart to a male superhero, but as an independent, title- COLLOQUY text theory critique 24 (2012). -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Wonder Woman by John Byrne Vol. 1 1St Edition Kindle

WONDER WOMAN BY JOHN BYRNE VOL. 1 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Byrne | 9781401270841 | | | | | Wonder Woman by John Byrne Vol. 1 1st edition PDF Book Diana met the spirit of Steve Trevor's mother, Diana Trevor, who was clad in armor identical to her own. In the s, one of the most celebrated creators in comics history—the legendary John Byrne—had one of the greatest runs of all time on the Amazon Warrior! But man, they sure were not good. Jul 08, Matt Piechocinski rated it really liked it Shelves: graphic-novels. DC Comics. Mark Richards rated it really liked it Mar 29, Just as terrifying, Wonder Woman learns of a deeper connection between the New Gods of Apokolips and New Genesis and those of her homeland of Themyscira. Superman: Kryptonite Nevermore. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. There's no telling who will get a big thrill out of tossing Batman and Robin Eternal. This story will appear as an insert in DC Comics Presents A lot of that is probably due to a general dislike for the 90s style of drawing superheroes, including the billowing hair that grows longer or shorter, depending on how much room there is in the frame. Later, she rebinds them and displays them on a platter. Animal Farm. Azzarello and Chiang hand over the keys to the Amazonian demigod's world to the just-announced husband-and-wife team of artist David Finch and writer Meredith Finch. Jun 10, Jerry rated it liked it. -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe.