Food Availability in the Poorest Households

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Environment Plan for Khunti District Jharkhand

DISTRICT ENVIRONMENT PLAN FOR KHUNTI DISTRICT JHARKHAND PREPARED BY DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION-KHUNTI CONTENT Index Page No. A. INTRODUCTION 1-2 B. CHAPTER- 1- A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF 3-6 KHUNTI DISTRICT C. CHAPTER- 2 - WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN (2.1) Solid Waste Management Plan 7-9 (2.1.1) Baseline Data 10-12 (2.1.2) Action Plan 12-13 (2.2) Plastic Waste Management Plan 14-15 (2.2.1) Baseline Data 16-17 (2.2.2) Action Plan 17-18 (2.3) C&D Waste Management Plan 18-19 (2.3.1) Baseline Data 20 (2.3.2) Action Plan 20-21 (2.4) Bio- Medical Waste Management Plan 21 (2.4.1) Baseline Data 22 (2.4.2) Action Plan 23 (2.5) Hazardous Waste Management Plan 24 (2.5.1) Baseline Data 24-25 (2.5.2) Action Plan 25 (2.6) E- Waste Management Plan 26 (2.6.1) Baseline Data 26-27 (2.6.2) Action Plan 28 D. CHAPTER- 3.1– WATER QUALITY 29 MANAGEMENT PLAN (3.1.1) Baseline Data 29-30 (3.1.2) Action Plan 31 District Environment Plan, Khunti. E. CHAPTER – 4.1 – DOMESTIC SEWAGE 32 MANAGEMENT PLAN (4.1.1) Baseline Data 32-33 (4.1.2) Action Plan 33-34 F. CHAPTER– 5.1– INDUSTRIAL WASTE WATER 35 MANAGEMENT PLAN (5.1.1) Baseline Data 35-36 G. CHAPTER – 6.1 – AIR QUALITY MANAGEMENT 37 PLAN (6.1.1) Baseline Data 37-38 (6.1.2) Action Plan 39 H. CHAPTER – 7.1 – MINING ACTIVITY 40 MANAGEMENT PLAN (7.1.1) Baseline Data 40 (7.1.2) Action Plan 40-41 I. -

District Health Society, Gumla Selected List for ANM MTC Adv

District Health Society, Gumla Selected List for ANM MTC Adv. At State O3lz0ts Total No of Post -08 Applicant Father's/Husband's Sl. No. Address Name Name t 2 3 4 Vill- Kapri,Po- Kumhari,Po+Ps- Basia Dt- t Rani Kumari Gokulnath Sahu Gumla,835229 2 Nutan Kumari Banbihari Sahu Vill+Po-Baghima,Ps-Palkot, Dt-Gum1a,835207 3 Sandhya Kurhari Mahesh Sahu Turunda,Po- Pokla gate,Ps-Kamdara,Dt- Gumla Vill-Kamdara,Tangratoli,Po+Ps- Kamdara,Dt- 4 Radhika Topno Buka Topno Gumla,835227 5 Rejina Tirkey Joseph Tirkey Vill+Po- Telgaon,Ps+Dt= Gumla,835207 6 Kiran Ekka Alexander Ekka Vill- Pugu karamdipa, Ps+Po- Gumla,835207 7 Rachna Rachita Bara Rafil Bara Vill- Tarri dipatoli,Po+Ps-Gum1a,835207 C/O Balacius Toppo,Vill-Sakeya,Po- Lasia,Ps- Basia, 8 Albina Toppo Balacius Toppo Dt- Grrmla F.?,\)11 District Health Society, Gumla Selected List for ANM - RBSK Adv. At State level OSl2OLs Total No of post - 22 Applicant Father's/Husband's Sl.No Address Name Name ,], 2 4 5 Vill- Kapri, P.O- Kumhari, P.S- Basia, Gumla 1, Rani Kumari Gokulnath Sahu 835229 Vill- Soso Kadam Toli, P.O+P.S+Dist-Gumla, 2 Jayanti Tirkey Hari Oraon 83s207 Vill+P.O- Baghima, P.S- Palkot, Gumla, 3 Nutan Kumari Ban Bihari Sahu 835207 Vill- Loyola Nagar, Gandhi Nagar, 4 Saroj Kumari Raghu Nayak P.O+P.S+Dist- G u mla, 835207 Vill- Sakya, P.O- Lasiya, P.S- Basia, Gumla, Teresa Lakra Gabriel Lakra 5 83s211 W/O- Syamsundar Thakur, Laxman Nagar, 6 Rajni Kumari Shyam Prasad Thakur P.O+P.S+Dist- G u m la, 835207 Vill- Puggu, Daud Nagar, P.O- Armai, 7 Rina Kumari Minz Gana Oraon P.S+Dist- Gu m la, -

RTC INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY Anandi, Ormanjhi, Ranchi - 835219 4 Year B.Tech Programmes

RTCIT A Premier Technical Institution RTC INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Anandi, Ormanjhi, Ranchi - 835219 4 YEAR B.TECH PROGRAMMES Civil Engineering 120 Computer Science and Engineering 60 For B.Tech : Students should have passed Intermediate, 10+2 or equivalent with minimum of 45% marks in PCM Electronics and Communication Engineering 60 (40% for SC/ST or OBC) and successful in any one of 1. JCECE conducted by Govt. of Jharkhand Electrical and Electronics Engineering 60 2. JEE (Main) by CBSE, New Delhi 3. Direct Admission to I.Sc or 10+2 passed students Lateral Entry for diploma holders in 2nd Year (3rd Information Technology 60 Semester) Mechanical Engineering 120 2 VISION DEDICATED TO DEVELOP AND FACILITATE AN EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF NATIONAL REPUTE BY SHARPENING TALENTS IN A DISCIPLINED AND CONDUCIVE ENVIRONMENT, PROVIDING QUALITY EDUCATION BY ACHIEVING EXCELLENCE. MISSION NURTURING GLOBAL TECHNOCRATS BY EMPOWERING THEM WITH QUALITY EDUCATION, HOLISTIC DEVELOPMENT AND WELL-ROUNDED PERSONALITIES 3 Our Chairman Our Guiding Sprit Essentially a Philanthropist and a visionary, a seasoned politician, Sri Ramtahal Choudhary is a person who dares to dream big and commands the ability to realize it. He dreamt of an educated elevated society and left no stone unturned in materializing the same. A four-time MP from the capital city of Ranchi, he has been looked up to as a man of utmost integrity and sincerity. He is identified as a significant force in transforming the very face of education in the state. The GAV SAMITI took shape about 36 years ago under his able leadership and went about building schools, Intermediate, degree and B. -

JHARKHAND - NOTIFIED PROTECTION OFFICERS (W.E.F

JHARKHAND - NOTIFIED PROTECTION OFFICERS (w.e.f. 11.06.2007) 1. Ms. Hema Choudhary, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Lapung, P.O. Lapung, Ranchi - 835244, Jharkhand. Ph. 9934172154 2. Smt. Abha Choudhary, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Ranchi Sadar, Kanke Road, Apar Shivpuri, Ranchi - 834008, Jhharkhand. Ph. 9431578415 3. Ms. Pushpa Tigga, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Angara, P.O. Angara, Ranchi – 835103, Jharkhand. Ph. 9431118906 4. Ms. Renu Ravi, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Chanho, P.O. Chanho, Ranchi - 835239, Jharkhand. Ph. 9431701597 5. Ms. Jyoti Kumari Prasad CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services Mandar, P.O. Mandar, Ranchi - 835214. Jharkhand Ph. 9130147188 6. Ms. Neeta Kumari Chouhan, ICDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Khijari, P.O. Namkum, Ranchi – 834010, Jharkhand. Ph. 9431465643 7. Ms. Sudha Sinha, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Bero, P.O. Berro, Ranchi – 835202, Jharkhand. Ph. 9431386449 8. Ms. Nirupama Shankar, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Ratu, P.O. Ratu, Ranchi - 835222, Jharkhand. 9. CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Bundu, P.O. Bundu, Ranchi - 835204, Jhharkhand. 10. Ms. Uma Sinha, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Tamar, P.O. Tamar, Ranchi – 835225, Jhharkhand. Ph. 9431312338 11. Ms. Surbhi Singh, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Ormanjhi, P.O. Ormanjhi, Ranchi - 835219, Jharkhand. Ph. 9431165293 12. CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Budmu, P.O. Budmu, Ranchi – 835214, Jharkhand. 13. Ms. Pooja Kumari, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Kanke, P.O. Kanke, Ranchi - 834006. Jharkhand Ph. 9431772461 14. Ms. Kanak Kumari Tirki, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Silli, P.O. Silli, Ranchi - 835103, Jharkhand. Ph. 9431325767 15. Ms. Lilavati Singh, CDPO, Integrated Child Development Services, Sonahatu, Post – Sonahatu, Ranchi - 835243, Jharkhand. -

Block Level Forecast

METEOROLOGICAL CENTRE, RANCHI INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT BLOCK LEVEL WEATHER FORECAST VALID TILL 0830 IST OF NEXT 5 DAYS AMFU, Ranchi : Districts of Central and North Eastern Plateau Zone FORECAST DISTRICTS BLOCK PARAMETERS DAY-1 DAY-2 DAY-3 DAY-4 DAY-5 17.04.21 18.04.21 19.04.21 20.04.21 21.04.21 BOKARO BOKARO Rainfall (mm) 2 0 0 0 0 Max Temperature ( deg C) 36 38 38 39 40 Min Temperature ( deg C) 25 25 23 22 24 Total cloud cover (octa) 4 3 2 0 0 Max Relative Humidity (%) 36 28 20 15 31 Min Relative Humidity (%) 9 12 11 6 6 Wind speed (kmph) 14 9 11 7 8 Wind direction (deg) 222 256 307 228 240 BOKARO BERMO Rainfall (mm) 2 0 0 0 0 Max Temperature ( deg C) 37 38 38 39 40 Min Temperature ( deg C) 25 25 23 22 24 Total cloud cover (octa) 4 3 2 0 0 Max Relative Humidity (%) 36 30 22 19 31 Min Relative Humidity (%) 9 12 11 6 6 Wind speed (kmph) 15 9 10 7 8 Wind direction (deg) 220 254 298 230 229 BOKARO CHANDANKIYARI Rainfall (mm) 2 0 0 0 0 Max Temperature ( deg C) 36 37 37 38 39 Min Temperature ( deg C) 25 24 21 22 24 Total cloud cover (octa) 3 3 2 0 0 Max Relative Humidity (%) 37 26 21 14 23 Min Relative Humidity (%) 10 12 11 7 7 Wind speed (kmph) 18 10 10 6 7 Wind direction (deg) 220 271 294 228 226 BOKARO CHANDRAPURA Rainfall (mm) 2 0 0 0 0 Max Temperature ( deg C) 36 38 38 39 40 Min Temperature ( deg C) 25 25 23 22 24 Total cloud cover (octa) 4 3 2 0 0 Max Relative Humidity (%) 36 28 20 15 31 Min Relative Humidity (%) 9 12 11 6 6 Wind speed (kmph) 14 9 11 7 8 Wind direction (deg) 222 255 306 228 239 BOKARO CHAS Rainfall (mm) 2 0 0 -

Interstate Routes in Between Odisha and Jharkhand

.,-. AIFEE LIST OF VACANT -INTERSTATE •ROUTES IN BETWEEN ODISH A AND JHARKHAND No., . Permits to No. of SI Distance of the Route in KMs Name of the routes be issued Trips Nature of No. J . by Service Jharkh W. Total Length Odisha Bihar Odisha Odisha and Bengal of the Route 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ,Bhadrak to Tata via.Balasore, 1 255 Baripada, Rairangpur, Tiring 40 0 0 295 1 1 Express Baripada to Chakulia 2 41 via.Jamsola 39 0 0 80 2 ' 4 Ordinary _ Bolani to Chaibasa via.Barbil, 3 40 Nalda, Badajamda 107 0 0 147 1 2 Ordinary Baripada to Bokaro 4 via.Rairangpur, Tiring, Tata, 118 166 0 64 348 2 2 -Express Purulia . Baripada to Musabani 5 40 via.Jamsola 45 0 0 85 3 6 Ordinary - . Chaibasa to Rairangpur 6 45 via.Tiring, Hata 120 0 . 0 165 1 • 2 Ordinary Chaibasa to Barbil via.Cha mpua, 7 65 Jayantgarh 67 0 0 132 1 2 Ordinary . Deoghar to Baripada via.Giridih, 8 Hazaribag, Ranchi, Tata, 118 500 0 0 618 2 2 •ExpFess . Rairangpur, Tiring • • 9 Gumla to Baripada via.Sisai, 118 270 0 Ranchi, Tata, Tiring, RaWangpur 388 2 2 express 10 Jharadihi to Saraikela via.Tata, Tiring 95 0 135 1 2 Ordinary Ranchi to Keonjhar via.Khunti, 11 195 0 0 Chaibasa, Champua 249 2 2 Ordinary Rourkela to Gua via.Barbil, 12 Nalda 20 0 0 194 1 2 Ordinary Simdega to Sundergarh 13 via.Subdega, Rouldega, 88 60 0 0 148 Sagbahal 1 2 Ordinary Simdega to Debgarh 14 via.Birmitrapur, Rourkela, 190 48 0 0 238 Panposh, Bonai, Barkot 1 1 Ordinary 15 Joda to Gumla via.Lasthikata, 175 130 0 0 Rourkela, Biramitrapur 305 1 1 .Express Baripada to Chatra via.Jamsola, 16 40 355 0 0 Tata, Ranchi 39'5 1 1 Express Baripada ato Daltanganj 17 via.Rairangpur, Tiring, Tata, 118 395 0 0 513 Ranchi 1 1 Express Berhampur to Tata via.Baripai 18 da, Jamsola renamed 483 235 0 0 as Berhampur to Ranchi 718 1 1 Expr-ess via.Jamsola, Tata • LIST OF VACANT INTERSTATE ROUTES PLYING BETWEEN ODISHA AND BIHAR PASSING THROUGH JHARKHAND THE . -

Ranchi District, Jharkhand State Godda BIHAR Pakur

भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका रा車ची स्जला, झारख車ड Ground Water Information Booklet Sahibganj Ranchi District, Jharkhand State Godda BIHAR Pakur Koderma U.P. Deoghar Giridih Dumka Chatra Garhwa Palamau Hazaribagh Jamtara Dhanbad Latehar Bokaro Ramgarh CHHATTISGARH Lohardaga Ranchi WEST BENGAL Gumla Khunti Saraikela Kharsawan SIMDEGA East Singhbhum West Singhbhum ORISSA के न्द्रीय भूमिजल बोड ड Central Ground water Board जल स車साधन ि車त्रालय Ministry of Water Resources (Govt. of India) (भारि सरकार) State Unit Office,Ranchi रा煍य एकक कायाडलय, रा更ची Mid-Eastern Region िध्य-पूर्वी क्षेत्र Patna पटना मसि車बर 2013 September 2013 भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका रा車ची स्जला, झारख車ड Ground Water Information Booklet Ranchi District, Jharkhand State Prepared By हﴂ टी बी एन स (वैज्ञाननक ) T. B. N. Singh (Scientist C) रा煍य एकक कायाडलय, रा更ची िध्य-पूर्वी क्षेत्र,पटना State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid Eastern Region, Patna Contents Serial no. Contents 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Administration 1.2 Drainage 1.3 Land use, Irrigation and Cropping pattern 1.4 Studies, activities carried out by C.G.W.B. 2.0 Climate 2.1 Rainfall 2.2 Temperature 3.0 Geomorphology 3.1 Physiography 3.2 Soils 4.0 Ground water scenario 4.1 Hydrogeology Aquifer systems Exploratory Drilling Well design Water levels (Pre-monsoon, post-monsoon) 4.2 Ground water Resources 4.3 Ground water quality 4.4 Status of ground water development 5.0 Ground water management strategy 6.0 Ground water related issues and problems 7.0 Awareness and training activity 8.0 Area notified by CGWA/SCGWA 9.0 Recommendations List of Tables Table 1 Water level of HNS wells in Ranchi district (2012) Table 2 Results of chemical analysis of water quality parameters (HNS) in Ranchi district Table 3 Block-wise Ground water Resources of Ranchi district (2009) List of Figures Fig. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN NO 26. MG ROAD AND ABERDEEN BAZAR , NICOBAR PORT BLAIR -744101 704412829 704412829 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR ,A & N ISLANDS PORT BLAIR IBKL0001498 8 7044128298 8 744259002 UPPER GROUND FLOOR, #6-5-83/1, ANIL ANIL NEW BUS STAND KUMAR KUMAR ANDHRA ROAD, BHUKTAPUR, 897889900 ANIL KUMAR 897889900 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD 504001 ADILABAD IBKL0001090 1 8978899001 1 1ST FLOOR, 14- 309,SREERAM ENCLAVE,RAILWAY FEDDER ROADANANTAPURA ANDHRA NANTAPURANDHRA ANANTAPU 08554- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR PRADESH R IBKL0000208 270244 D.NO.16-376,MARKET STREET,OPPOSITE CHURCH,DHARMAVA RAM- 091 ANDHRA 515671,ANANTAPUR DHARMAVA 949497979 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM DISTRICT RAM IBKL0001795 7 515259202 SRINIVASA SRINIVASA IDBI BANK LTD, 10- RAO RAO 43, BESIDE SURESH MYLAPALL SRINIVASA MYLAPALL MEDICALS, RAILWAY I - RAO I - ANDHRA STATION ROAD, +91967670 MYLAPALLI - +91967670 PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL GUNTAKAL - 515801 GUNTAKAL IBKL0001091 6655 +919676706655 6655 18-1-138, M.F.ROAD, AJACENT TO ING VYSYA BANK, HINDUPUR , ANANTAPUR DIST - 994973715 ANDHRA PIN:515 201 9/98497191 PRADESH ANANTAPUR HINDUPUR ANDHRA PRADESH HINDUPUR IBKL0001162 17 515259102 AGRICULTURE MARKET COMMITTEE, ANANTAPUR ROAD, TADIPATRI, 085582264 ANANTAPUR DIST 40 ANDHRA PIN : 515411 /903226789 PRADESH ANANTAPUR TADIPATRI ANDHRA PRADESH TADPATRI IBKL0001163 2 515259402 BUKARAYASUNDARA M MANDAL,NEAR HP GAS FILLING 91 ANDHRA STATION,ANANTHAP ANANTAPU 929710487 PRADESH ANANTAPUR VADIYAMPETA UR -

49125-001: Khunti-Tamar Road Resettlement Plan

Resettlement Plan March 2015 IND: Second Jharkhand State Road Project Khunti - Tamar Road Prepared by State Highways Authority of Jharkhand (SHAJ), Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of March 2015) Currency Unit – Indian Rupee (INR) INR 1.00 = 0.016 USD USD 1.00 = INR 62 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AHH Affected Households AP Affected Person BSR Basic Schedule of Rates CPR Common Property Resources EA Executing Agency EE Executive Engineer FGD Focus Group Discussion FHH Female Headed Household GoI Government of India GoJH Government of Jharkhand GRC Grievance Redress Committee GRM Grievance Redressal Mechanism IR Involuntary Resettlement KMS Kilometers LA Land Acquisition LARC Land Acquisition and Resettlement Commission MAW Minimum Agriculture Wage M&E Monitoring & Evaluation NGO Non-Governmental Organization NRRP National Resettlement Rehabilitation Policy PMU Project Management Unit PIU Project Implementation Unit RFCLARRA, 2013 The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 R&R Resettlement & Rehabilitation RO Resettlement Officer RP Resettlement Plan RoW Right-of-Way SC Scheduled Caste SPS Safeguard Policy Statement (ADB 2009) ST Scheduled Tribe This Resettlement Plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Of 258 SL. No. Page No. Name of Advocates Address Phone &Mobile

SL. No. Page No. Name of Advocates Enrolment No. Date of Enrol. Asso. Member Address Phone &Mobile no. 1 786 A.Sumir Kumar Sinha 617/2008 13/08/2008 16/09/2008 Amrawati Colony, Near Ranchi Railway 9835340442 Colony, South, P.O.- Chutia, P.S.-Chutia, 9576126246 Ranchi. 2 750 Aabhas Parimal D/1171/2007 1/9/2007 10/12/2007 3 248 Aashutosh Kumar 41/2001 18/4/01 30/10/01 4 205 Abbinus Oreo 182/1989 24/2/89 16/3/01 5 15 Abdul Allam, Sr.Adv. 158/1981 24/2/1981 12/7/1984 6 201 Abdul Hakim 72/1974 5/3/1974 24/1/01 7 41 Abdul Kalam Rashidi 376/1990 23/3/90 28/1/91 Lane No.-5, Sattar Colony, Bariatu, 09835536572 Ranchi-834009 09304191572 8 280 Abha Sinha 1407/2002 9/11/2002 13/1/03 9 279 Abhas Kumar Pandey 3076/2000 18/8/2k 13/1/03 92, Malti Kunj, Jyoti Path, S.P. Colony 9661879595 Road, Diebdih, Doranda, Ranchi-834002 10 262 Abhay Kumar 1271/1999 9/4/1999 10/6/2002 Page 1 of 258 SL. No. Page No. Name of Advocates Enrolment No. Date of Enrol. Asso. Member Address Phone &Mobile no. 11 19 Abhay Kumar Chaturvedy 1411/1983 16/12/1983 7/1/1985 Sukhdeo Nagar, Ratu Road, Ranchi. 0651-2282923 12 184 Abhay Kumar Mishra 2322/2000 15/5/2000 6/7/2k House No.14, Road No.-1, Birsa Nagar, 9431101731 Hatia Station Road, Hatia, Ranchi. 13 678 Abhay Kumar Tiwari 5580/1995 12/12/1995 11/5/2006 14 713 Abhay Prakash 151/2007 28/02/2007 9/4/2007 33k, Madhukum Lane, Ratu Road, Ranchi- 9431579611 5 15 5 Abhay Shankar Dayal 455/475/1976 13/7/76 13/1/1977 Dayal Niwas, Tharpakhna, Ranchi. -

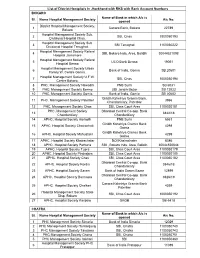

List of District Hostpitals in Jharkhand with RKS with Bank Account Numbers BOKARO Name of Bank in Which A/C Is Sl

List of District Hostpitals In Jharkhand with RKS with Bank Account Numbers BOKARO Name of Bank in which A/c is Sl. Name Hospital Management Society A/c No. opened District Hospital Management Society, 1 Canara Bank, Bokaro 22789 Bokaro Hospital Management Society Sub. 2 SBI, Chas 1000050193 Divisional Hospital Chas. Hospital Management Society Sub. 3 SBI Tenughat 1100050222 Divisional Hospital Tenughat. Hospital Management Society Referal 4 SBI, Bokaro Inds, Area, Balidih 30044521098 Hospital Jainamore Hospital Management Society Referal 5 UCO Bank Bermo 19051 Hospital Bermo Hospital Management Society Urban 6 Bank of India, Gomia SB 20601 Family W. Centre Gomia. Hospital Management Society U.F.W. 7 SBI, Chas 1000050194 Centre Bokaro. 8 PHC. Management Society Nawadih PNB Surhi SB 6531 9 PHC. Management Society Bermo UBI Jaridih Bazar SB 12022 10 PHC. Management Society Gomia Bank of India, Gomia SB 20602 Giridih Kshetriya Gramin Bank, 11 PHC. Management Society Paterber 3966 Chandankiary, Paterbar 12 PHC. Management Society Chas SBI, Chas Court Area 1100020181 PHC. Management Society Dhanbad Central Co-opp. Bank 13 3844/18 Chandankiary Chandankiary 14 APHC. Hospital Society Harladih PNB Surhi 6551 Giridih Kshetriya Gramin Bank 15 APHC. Hospital Society Chatrochati 4298 Goima Giridih Kshetriya Gramin Bank 16 APHC. Hospital Society Mahuatanr 4299 Goima 17 APHC. Hospital Society Khairachatar BOI Khairachater 8386 18 APHC. Hospital Society Pathuria SBI , Bokaro Inds. Area, Balidih 30044520844 19 APHC. Hospital Society Tupra SBI, Chas Court Area 1100050179 20 APHC. Hospital Society Pindrajora SBI, Chas Court Area 1100050180 21 APHC. Hospital Society Chas SBI, Chas Court Area 1100050182 Dhanbad Central Co-opp. -

Disparities in Infrastructural Development in Ranchi

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Disparities in Infrastructural Development in Ranchi Lochana Koirala Research Scholar (SRF), Department of Geography, Ranchi University, Ranchi, India Abstract: Infrastructure is the foundation for the development of any country; Infrastructural facilities are the wheels of development which plays a decisive role in determining the overall productivity and development of country’s economy as well as the quality of life of the citizens. This paper highlights the intra-district disparities in infrastructural facilities in Ranchi district using seven indicators viz. education, health, financial services, transport and communication and public utilities. An attempt has been made to examine the spatial disparities in infrastructural and rural development across the district, considering block as a unit of analysis, using simple multivariate method to construct a composite infrastructure development index (IDI) by combining various infrastructural facilities at the block level. The paper concludes suggesting suitable policies for developing the backward areas which would further aid in enhancing the levels of socio-economic development of Jharkhand. Keywords: Disparities, Infrastructural facilities, development 1. Introduction Efficiency, quality of these facilities is not uniform across the entire region. Disparities exist along all the hierarchical levels The word development report published in 1994 by the World of Administration from state to block level which is reflected Bank under the title “Infrastructure for development” rightly in both inter and intra forms. Disparities in economic mentions that the adequacy of infrastructure helps determine development can be explained in terms of varying level of one country‟s success and another‟s failure in diversifying infrastructural facilities to people in different regions.