Saint Benedict of Aniane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monastic Rules of Visigothic Iberia: a Study of Their Text and Language

THE MONASTIC RULES OF VISIGOTHIC IBERIA: A STUDY OF THEIR TEXT AND LANGUAGE By NEIL ALLIES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham July 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis is concerned with the monastic rules that were written in seventh century Iberia and the relationship that existed between them and their intended, contemporary, audience. It aims to investigate this relationship from three distinct, yet related, perspectives: physical, literary and philological. After establishing the historical and historiographical background of the texts, the thesis investigates firstly the presence of a monastic rule as a physical text and its role in a monastery and its relationship with issues of early medieval literacy. It then turns to look at the use of literary techniques and structures in the texts and their relationship with literary culture more generally at the time. Finally, the thesis turns to issues of the language that the monastic rules were written in and the relationship between the spoken and written registers not only of their authors, but also of their audiences. -

2-KORNELIMÜNSTER Pilgrimages in the Rhineland in the Late Middle

2-KORNELIMÜNSTER Pilgrimages in the Rhineland In the late Middle Ages, localities situated along the major pilgrimage routes, “peregrinationes maiores”, to Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela, and which themselves possessed holy relics of secondary value, began to develop as places of pilgrimage. One such locality was Aachen, on a par with the Maria Hermitage in Switzerland or Vézelay in Burgundy. By augmenting the degree of grace or indulgence they could offer, they drew more pilgrims. Already prior to the time of Charlemagne, the first pilgrims came to Aachen. In the Middle Ages, Aachen was considered the most important place of pilgrimage in the Germanic regions. Following a period of prohibition during the Enlightenment, pilgrimage picked up again in the 19 th century. Noteworthy is the Aachener Pilgrimage of 1937 which, despite attempts by the Nazis to disrupt it, still managed to mobilise 800,000 pilgrims, under the leadership of future Cardinal Clemens August Graf von Galen, in a silent protest. In the Holy Year 2000, more than 90,000 pilgrims took part in the journey to Aachen. Other pilgrimage destinations in the Rhineland are Mönchengladbach and Kornelimünster. In addition, there is a pilgrimage every seven years to the tomb of Saint Servatius in neighbouring Maastricht. The next date for this is in 2018, which is also the year in which the oldest city in the Netherlands, together with other boroughs in the Euregio Maas-Rhein, is aiming to be chosen as European Capital of Culture. Pilgrimage, motives with accents To feel the nearness of God - this is the goal of many of those believers who travel to the world’s great religious sites. -

Benedictionary.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The inspiration for this little booklet comes from two sources. The first source is a booklet developed in 1997 by Father GeorgeW. Traub, S.j., titled "Do You Speak Ignatian? A Glossary ofTerms Used in Ignatian and]esuit Circles." The booklet is published by the Ignatian Programs/Spiritual Development offICe of Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio. The second source, Beoneodicotionoal)', a pamphlet published by the Admissions Office of Benedictine University, was designed to be "a useful reference guide to help parents and students master the language of the college experience at Benedictine University." This booklet is not an alphabetical glossary but a directory to various offices and services. Beoneodicotio7loal)' II provides members of the campus community, and other interested individuals, with an opportunity to understand some of the specific terms used by Benedictine men and women. \\''hile Benedictine University makes a serious attempt to have all members of the campus community understand the "Benedictine Values" that underlie the educational work of the University, we hope this booklet will take the mystery out of some of the language used commonly among Benedictine monastics. This booklet was developed by Fr. David Turner, a,S.B., as part of the work of the Center for Mission and Identity at Benedictine University. I ABBESS The superior of a monastery of women, established as an abbey, is referred to as an abbess.. The professed members of the abbey are usually referred to as nuns. The abbess is elected to office following the norms contained in the proper law of the Congregation ohvhich the abbey is a member. -

Cluny and Gregory VII

20 CLVNY AND GBEGOBY VII Jan. Cluny and Gregory VII N the desolate years that opened the tenth century Cluny set Downloaded from I the example of religious duty and discipline and of dignity of service. Born in an age of coarse materialism, she sought to recall to men that interest in spiritual things which seemed to have been lost, and to do so by setting up an ideal in direct contradiction to the spirit rife in the world around her. The spirit of devotion http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ •which was the motive of her foundation she hoped to stimulate beyond her own walls.1 Thus from her origin she was zealous for monastic reform. Such indeed was necessary, for the invasions of the Normans had almost swept away monasticism in Gaul.2 Into Burgundy however the Normans had scarcely penetrated, and the position of Cluny made her a good centre for radiating reform. Protected by her gently swelling hills, she lay near one of the pilgrim routes to Eome, and close to the highways of the Saone at UB Giessen on July 14, 2015 and Bhone; while placed as she was on neutral ground, conveniently distant from and practically independent of both Teutonic emperor and Frankish king, the conditions were favourable for the mainten- ance of her principle of monastic autonomy. The character of her early abbots too, men of eminent virtue, made for her success, as also did the rule they adopted—the Benedictine modified by Benedict of Aniane and the Aachen capitularies.3 Not only so, but unlike the almost contemporary but more ascetic reform of the Italian hermits, who looked to the East for their inspiration, Cluny, essentially Western, stood for moderation. -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 93: St. Benedict & Western Monasticism A Devoted Life: Did You Know? Interesting and little-known facts about Benedictine monasticism. A living tradition Today there are about 25,000 Benedictine monks and nuns, as well as over 5,000 Cistercians and others who live according to the Rule of St. Benedict. In the last 40 years, these numbers have been declining, but the number of "oblates," lay people associated with monasteries, is growing rapidly and now exceeds the number of monks and nuns. Many of them are Protestants. —contributed by Hugh Feiss, OSB Walking in Benedict's steps today Visit Clear Creek Monastery in Oklahoma and you will see something as close to 12th-century Benedictine monastic life as can be found in the 21st century. It all began in 1972 when a group of University of Kansas students discovered Fontgombault, a traditional Benedictine monastery in France known for its Gregorian chant, traditional Latin liturgy, and strict adherence to the Rule of St. Benedict. Around 30 students stayed at the abbey as guests, and a handful never left. The abbot of Fontgombault called it the "American Invasion." Now Fontgombault has come to America. The students-turned-monks returned to the U.S. in the 1990s and founded Clear Creek Monastery. There, they continue to pursue a traditional Benedictine lifestyle. Talk to the hand Benedict encouraged his monks to be silent as often as possible. But of course, some form of communication is necessary in order for people to live together. In The Year 1000, Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger describe a Benedictine sign language manual from Canterbury listing no less than 127 hand signals, including signs for various people in the monastery, ordinary objects such as a pillow ("Stroke the sign of a feather inside your left hand"), and requests such as "Pass the salt" ("Stroke your hands with your three fingers together, as if you were salting something"). -

Manual Labor: the Twelfth-Century Cistercian Ideal

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1984 Manual Labor: The Twelfth-Century Cistercian Ideal Dennis R. Overman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Overman, Dennis R., "Manual Labor: The Twelfth-Century Cistercian Ideal" (1984). Master's Theses. 1525. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1525 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUAL LABOR: THE TWELFTH-CENTURY CISTERCIAN IDEAL by Dennis R. Overman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Medieval Studies Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1984 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. MANUAL LABOR: THE TWELFTH-CENTURY CISTERCIAN IDEAL Dennis R. Overman, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1984 Throughout the history of western monasticism three principal occupations were repeatedly emphasized for the monk: prayer, lectio divina (spiritual reading/meditation), and manual labor. Periodically, cultural mindsets, social structure, or even geography have produced a variation in the practice of these occupations, resulting in the dominance of one or the other, or even the disappearance of one altogether. The emergence of the Cistercian Order at the end of the eleventh century was characterized by a spirit of simplicity and austerity with a renewed emphasis on manual labor which had been a neglected element in the monastic regime in the period just prior to the Cistercians. -

Church History L6--The Monastic Movement

Who’s Who in Church History Lesson Six the Monastic Movement Benedict of Nursia Bernard of Clairvaux Why All the Monk Business? Monasteries played an essential role in the development of the Western church. This is surprising to us for a number of reasons. One of these reasons is the popularity of an overwhelmingly negative portrait that does not do justice to the monastic world. One aspect of We get our English word that portrait reduces the role of the monastery to that of “monk” from the latin word “monachus” which the “librarians of the West during the Dark Ages,” just in turn came from the holding and dutifully copying works until the bright guys Greek and means “single, of the Renaissance show up to actually read and alone, unique”. understand them. The other view portrays monasteries as some kind of asylum for anti-social misfits, for those who couldn’t cut it in the real world, or, worse, the deviant. Finally, in our society anyone who would take vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity just has to be plain silly, right? Not quite. As Christians, we can find much to be thankful for coming out of the monastic world. Monasteries were the spiritual laboratories of their day. The goal was to create stable, spiritual communities that through the application of spiritual disciplines might bring about righteousness for the individual and the larger community. The monastery was the designated place of worship; regular hours were set up so that worship might continue all day long and musical forms were developed that remain in place today. -

Abd Ar-Rahman III 188 Abhayagiri Monastery 335 Abraham 357

Index Abd ar-Rahman III 188 Baghdad 189, 192, 291, 294, 299, 354, 360 Abhayagiri monastery 335 Bahāʾal-Dīn ibn Shaddād 3 Abraham 357 Baoyu 90 Abraham ibn Ezra 194–197, 198 n. 33 Baraz, Daniel 211 Abu Zayd 307–308 Basse-Loire 208 Acre 303 Baudri of Dol 300 Adam 122–123, 130 Baumgarten, Elisheva 56 Aelred of Rievaulx, 141 Beaulieu 214 Aggabodhi V 337 n. 48 Beauvais 222–223, 227 Al-Andalus (Andalusia) 4, 11, 185, 192–198, Bede the Venerable 120–122, 124–126, 128 304 Belgium 208 Al-Azmeh, Aziz 9, 13–14, 16, 348–366 Benedict of Aniane 219 Al-Basāsīrī 360 Berlin 1 Al-Bukhārī 354 Berry 217 Alcuin of York 135–136, 219, 223 Bischoff, Bernhard 227 Alexandria 308 n. 38 Bley, Matthias 11, 16, 203–239 Alfonso, Esperanza 189, 193 Blois 217 Al-Ghazālī 362 Bombay see Mumbai Allony, Nehemia 187 Bonn 59 Al-Malik al-Kāmil 315 Bretfeld, Sven 13, 16, 320–347 Alphonse III of Asturias 226, 227 n. 106 Bristol 58 Althusser, Louis 350 Brittany 208 Amalar of Metz 135, 137 Brunettin, Giordano 313 Andalusia see al-Andalus Bruno of Asti 129–130 Andernach 58 Buddhabhadra 174 Angelo Clareno 313–316 Buddhaghosa 14, 320, 322–326, 328–335, Angelo di Castro 4, 5 344 Angenendt, Arnold 25–27, 30, 36, 118–119, 142 Calderoli, Roberto 1 Angers 210–211, 217 Cao Xueqin 102, 105 Anselm of Canterbury 139 Carrithers, Michael 330 Anselm of Laon 140 Cecilia of Spello 304 Anthony of Padua 304 Chablis 217 Antiochus IV Epiphanes 206, 278 Chanah 278 Anurādhapura 331 n. -

The Historical Development of Christian Worship

300 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF CHRISTIAN WORSHIP THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF CHRISTIAN WORSHIP. BY THE REV, A. J. MACDONALD, D.D., Rector of St. Dunstan's-in-the-West, Fleet Street. T is a mistake to suppose that Christian worship has developed I from the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, and that the central feature of worship has always been the celebration of the Eucharist. We read in the Acts that in the interval between the Resurrection and Pentecost the apostles went daily to the Temple for prayer, that is to say they continued to observe the ancient Jewish hours of prayer ; and if we read later, that they broke bread together on the first day of the week, and broke it " at home '' ; this is not evidence that the old habits of prayer, fostered by Temple and synagogue worship, were allowed to be displaced. The Eucharist in its earlier stages was a fellowship-meal, accompanied by prayers and praises, intended to conserve the social character of the Last Supper, although hallowed by a marked religious tendency. It was the Agape. In the second century, owing partly to the difficulty of catering for the growing Christian communities, the Agape fell into disuse, and the Eucharist or service of Holy Communion lost much of its original social character, and became solely an act of religious worship. This Eucharist for many decades was celebrated not more than once a week, and a survival of this practice is clearly traced in the habits of the Egyptian ascetics of the fourth and fifth centuries who did not come together for Holy Communion more than once, or sometimes twice a week. -

“A Benedictine Reader Is an Exciting Volume of Sources That Includes Key Texts from the Order’S Inception in 530 Through the Sixteenth Century

“A Benedictine Reader is an exciting volume of sources that includes key texts from the Order’s inception in 530 through the sixteenth century. These ‘Benedictine Centuries’ demonstrate the rich and varied contributions that knit together the religious, political, social, and cultural fabric of European society throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern period. Translated into fresh and readable English, each text contains a concise introduction that has an almost intuitive quality. This is a welcome addition to the field and is an excellent resource for both scholars and students alike.” —Alice Chapman Associate Professor of History Grand Valley State University “Perfectae Caritatis invited religious to enter into their original sources and primitive inspirations. A Benedictine Reader achieves this by creating a fascinating world of medieval monastic doctrine. This anthology opens up for any interested person ancient sources that fashioned monastic aggiornamento through the centuries. With quite remarkable scholarship, the wealth of footnotes in this volume introduces contemporary authorities promoting this renewal. Together these ancient monastics and contemporary scholars form a valuable treasure for a rebirth in monastic wisdom and insight.” —Thomas X. Davis, OCSO Abbot Emeritus, New Clairvaux Abbey “A Benedictine Reader brings together in a single volume the Venerable Bede, John of Fécamp, Abelard, Hildegard of Bingen, and other well-known figures of Western medieval monasticism. Also included are lesser known authors and works by anonymous voices. This virtual library of medieval Benedictine texts fills a gaping hole in monastic libraries and will be an excellent resource in monastic formation programs.” —Mark A. Scott, OCSO Abbot of New Melleray Peosta, Iowa 48 42 49 44 47 46 45 50 43 41 2 17 19 18 15 51 3 40 14 16 38 1 39 20 52 13 37 21 12 9 10 11 36 22 8 32 33 34 35 53 23 7 4 6 6 30 31 5 25 27 29 24 26 28 The Plan of St. -

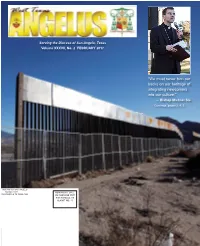

WTA2017-02.Pdf

Serving the Diocese of San Angelo, Texas Volume XXXVII, No. 2 FEBRUARY 2017 “We must never turn our backs on our heritage of integrating newcomers into our culture.” — Bishop Michael Sis Coverage, pages 2, 4, 5 DIOCESE OF SAN ANGELO PO BOX 1829 NONPROFIT ORG. SAN ANGELO TX 76902-1829 US POSTAGE PAID SAN ANGELO, TX PERMIT NO. 44 Page 2 FEBRUARY 2017 The Angelus The Inside Front Jesuit priest to share thoughts on how not to say Mass "Faith grows when it is well expressed in celebration. and the Roman Missal” (Paulist that length, Fr. Smolarski said, are hard to find and sug- Good celebrations can foster and nourish faith. Press, 2005). gested that homilies are most effective if they are no Poor celebrations may weaken it." In his book, written primarily but longer than five minutes in daily Mass and between 8- — “Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship” (USCCB 2007) not exclusively for priests, Fr. 10 minutes on Sundays. Homilies any longer, Fr. Smolarski delves into all aspects of Smolarski said, should be confined to feast days or spe- By Jimmy Patterson the liturgy from introductory rites to cial celebrations. Editor / West Texas Angelus concluding rites. Not surprisingly, “One thing priests can learn is to not overdo it,” he much attention has been given to said. “The hardest sermons to write are the shortest.” SAN ANGELO — Priests from throughout the homilies. Another good rule of thumb: Only leave those in the Diocese of San Angelo will gather February 20-21 to Fr. Smolarski quotes from Bishop pews with a maximum of 3-5 “nuggets,” as he calls hear how not to say the Mass. -

Economics of Monasticism

The Economics of Monasticism Nathan Smith September 6, 2009 ABSTRACT: Since their emergence in ancient times, Christian monasteries have proven to be among the most durable of all human institutions, and in the medieval centuries made enormous contributions to the emergence of Western civilization. They are organized internally on socialist lines: monks own no property and owe total obedience to the abbot, making the monastery a miniature ‘centrally planned economy.’ A puzzling contrast exists between the longevity of monasteries and the transience of secular socialist communes. This paper presents a theoretical model which shows why voluntary socialist communes might be viable despite ‘shirking’ problems, yet fail due to turnover, and how worship , which induces people with high ‘spiritual capital’ to self-select into the monastery and then grows that spiritual capital through ‘learning-by-doing,’ can solve the turnover problem and make a worship-based socialist commune—a monastery—stable. Monasticism, like the market, is a form of ‘spontaneous order,’ but unlike the market, it does not depend on third-party enforcement (e.g., by a state) to function: this explains why monasticism (unlike capitalism) was able to thrive in the anarchic Dark Ages. Monasteries, in principle and largely in practice, are a form of society based on consent of the governed, unlike liberal states which preach but do not practice consensual governance, and it is interesting to juxtapose the real, live ‘social contracts’ of the monasteries with the notional social contracts of liberal political theory. KEYWORDS: Religion, economic history, Middle Ages, socialism, communes, social contract, spontaneous order, liberal ideology, clubs JEL: N00, N33, N43, D02, D23, D70, P32, P50, J41, J12, B15 1 For man’s character has been moulded by his every-day work, and the material resources which he thereby procures, more than by any other influence unless it be that of his religious ideals; and the two great forming agencies of the world’s history have been the religious and the economic.