Assessing Al-Qaeda's Chemical Threat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“New” Vs. “Old” Terrorism*

The Debate over “New” vs. “Old” Terrorism* Prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, Illinois, August 30-September 2, 2007 Martha Crenshaw Center for International Security and Cooperation Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6165 [email protected] Since 9/11, many policy makers, journalists, consultants, and scholars have become convinced that the world confronts a “new” terrorism unlike the terrorism of the past.1 Thus the government and policy elites have been blamed for not recognizing the danger of the “new” terrorism in the 1990s and therefore failing to prevent the disaster of 9/11.2 Knowledge of the “old” or traditional terrorism is sometimes considered irrelevant at best, and obsolete and anachronistic, even harmful, at worst. Some of those who argue 1 Examples include Bruce Hoffman, Inside Terrorism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), although Hoffman is sometimes ambivalent; Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, The Age of Sacred Terror: Radical Islam’s War Against America (New York Random House, 2003); Walter Laqueur, The New Terrorism: Fanaticism and the Arms of Mass Destruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); and Ian O. Lesser, et al., Countering the New Terrorism (Santa Monica: The Rand Corporation, 1999). Ambassador L. Paul Bremer contributed “A New Strategy for the New Face of Terrorism” to a special issue of The National Interest (Thanksgiving 2001), pp. 23-30. A recent post 9/11 overview is Matthew J. Morgan, “The Origins of the New Terrorism,” Parameters (the journal of the U.S. Army War College), 34, 1 (Spring 2004), pp. -

The 2002 National Security Strategy: the Foundation Of

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Graduate Program in International Studies Theses & Graduate Program in International Studies Dissertations Summer 2013 The 2002 aN tional Security Strategy: The Foundation of a Doctrine of Preemption, Prevention, or Anticipatory Action Troy Lorenzo Ewing Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/gpis_etds Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, International Law Commons, Terrorism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Troy L.. "The 2002 aN tional Security Strategy: The oundF ation of a Doctrine of Preemption, Prevention, or Anticipatory Action" (2013). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, International Studies, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ 8f8q-9g35 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/gpis_etds/46 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Program in International Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Program in International Studies Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE 2002 NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY: THE FOUNDATION OF A DOCTRINE OF PREEMPTION, PREVENTION, OR ANTICIPATORY ACTION by Troy Lorenzo Ewing B.A. May 1992, Rutgers University M.B.A. May 2001, Webster University M.S.S.I. May 2007, National Intelligence University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL STUDIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2013 ABSTRACT THE 2002 NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY: THE FOUNDATION OF A DOCTRINE OF PREEMPTION, PREVENTION, OR ANTICIPATORY ACTION Troy Lorenzo Ewing Old Dominion University, 2013 Director: Dr. -

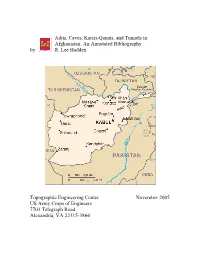

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: an Annotated Bibliography by R

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography by R. Lee Hadden Topographic Engineering Center November 2005 US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Alexandria, VA 22315-3864 Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels In Afghanistan Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE 30-11- 2. REPORT TYPE Bibliography 3. DATES COVERED 1830-2005 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER “Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats and Tunnels 5b. GRANT NUMBER In Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography” 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER HADDEN, Robert Lee 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Topographic Alexandria, VA 22315- Engineering Center 3864 9.ATTN SPONSORING CEERD / MONITORINGTO I AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Disaster Response and Biological/Chemical Terrorism

Disaster Response and Biological/Chemical Terrorism Information Packet Prepared by: Emergency Medical Services Department October 2001 Disaster Response and Biological/Chemical Terrorism Clearinghouse Information The College has been very active in disaster planning and response as well as biological/chemical terrorism preparation for a number of years. The membership section, Disaster Medicine, was the first membership section organized in 1989. They have been one of the largest in membership and one of the most active. The EMS Department maintains information for members and the public on disaster response and biological/chemical terrorism topics in a variety of formats and publications. POLICY STATEMENTS The College has current policies addressing the following: · Disaster Data Collection (Oct. 2000) · Disaster Medical Service (June 2000) · Support for National Disaster Medical System-NDMS (Mar. 1999) · Handling of Hazardous Materials (June 1999) TEXT BOOKS The College developed and published the text: Community Medical Disaster Planning and Evaluation Guide through a section grant with the Disaster Medicine Section. This is an excellent guide for developing or updating a hospital or city/county disaster plan. While biological or chemical agents are not specifically mentioned, many of the same disaster planning and response issues remain the same. This text can be ordered through the College bookstore at 1-800-798- 1822, ext. 6for $69.00, item number 513000-1020. NBC TASK FORCE The College’s nuclear, biological and chemical (NBC) Task Force recently completed a grant with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP) to develop objectives, content and competencies for the training of emergency medical technicians, emergency physicians, and emergency nurses to care for casualties resulting from nuclear, biological, or chemical (NBC) incidents. -

Volume X, Issue 2 April 2016 PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 2

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume X, Issue 2 April 2016 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 2 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editor 1 I. Articles ‘Gonna Get Myself Connected’: The Role of Facilitation in Foreign Fighter Mobilizations 2 by Timothy Holman II. Special Correspondence to Perspectives on Terrorism Why Has The Islamic State Changed its Strategy and Mounted the Paris-Brussels Attacks? 24 by David C. Rapoport III. Research Notes Analysing the Processes of Lone-Actor Terrorism: Research Findings 33 by Clare Ellis, Raffaello Pantucci, Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn, Edwin Bakker, Melanie Smith, Benoît Gomis and Simon Palombi Analysing Personal Characteristics of Lone-Actor Terrorists: Research Findings and Recommendations 42 by Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn and Edwin Bakker Evaluating CVE: Understanding the Recent Changes to the United Kingdom’s Implementation of Prevent 50 by Caitlin Mastroe In Conversation with Mubin Shaikh: From Salafi Jihadist to Undercover Agent inside the “Toronto 18” Terrorist Group 61 Interview by Stefano Bonino IV. Resources Bibliography: Terrorism Research Literature (Part 2) 73 Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes V. Book Reviews Counterterrorism Bookshelf: 30 Books on Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism-Related Subjects 103 Reviewed by Joshua Sinai ISSN 2334-3745 i April 2016 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 2 VI. Notes from the Editor Op-Ed: Competing Perspectives on Countering ISIS 118 by Hashim Al-Ribaki Conference Announcement and Call for Proposals 120 About Perspectives on Terrorism 122 ISSN 2334-3745 ii April 2016 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 2 Welcome from the Editor Dear Reader, We are pleased to announce the release of Volume X, Issue 2 (April 2016) of Perspectives on Terrorism at www.terrorismanalysts.com. -

Two Cheers for Bargaining Theory Two Cheers for David A

Two Cheers for Bargaining Theory Two Cheers for David A. Lake Bargaining Theory Assessing Rationalist Explanations of the Iraq War The Iraq War has been one of the most signiªcant events in world politics since the end of the Cold War. One of the ªrst preventive wars in history, it cost trillions of dollars, re- sulted in more than 4,500 U.S. and coalition casualties (to date), caused enor- mous suffering in Iraq, and may have spurred greater anti-Americanism in the Middle East even while reducing potential threats to the United States and its allies. Yet, despite its profound importance, the causes of the war have re- ceived little sustained analysis from scholars of international relations.1 Al- though there have been many descriptions of the lead-up to the war, the ªghting, and the occupation, these largely journalistic accounts explain how but not why the war occurred.2 In this article, I assess a leading academic theory of conºict—the rationalist approach to war or, simply, bargaining theory—as one possible explanation of the Iraq War.3 Bargaining theory is currently the dominant approach in conºict David A. Lake is Jerri-Ann and Gary E. Jacobs Professor of Social Sciences, Distinguished Professor of Political Science, and Associate Dean of Social Sciences at the University of California, San Diego. He is the author, most recently, of Hierarchy in International Relations (Cornell University Press, 2009). The author is indebted to Peter Gourevitch, Stephan Haggard, Miles Kahler, James Long, Rose McDermott, Etel Solingen, and Barbara Walter for helpful discussions on Iraq or comments on this article. -

Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons

VERSION: Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, eds., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 193-238. c h a p t e r 8 Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons Charles P. Blair CONTENTS Introduction 193 Improvised Nuclear Devices (INDs) 195 Fissile Materials 198 Weapons-Grade Uranium and Plutonium 199 Likely IND Construction 203 External Procurement of Intact Nuclear Weapons 204 State Acquisition of an Intact Nuclear Weapon 204 Nuclear Black Market 212 Incidents of Jihadist Interest in Nuclear Weapons and Weapons-Grade Nuclear Materials 213 Al-Qa‘ida 213 Russia’s Chechen-Led Jihadists 214 Nuclear-Related Threats and Attacks in India and Pakistan 215 Overall Likelihood of Jihadists Obtaining Nuclear Capability 215 Notes 216 Appendix: Toward a Nuclear Weapon: Principles of Nuclear Energy 232 Discovery of Radioactive Materials 232 Divisibility of the Atom 232 Atomic Nucleus 233 Discovery of Neutrons: A Pathway to the Nucleus 233 Fission 234 Chain Reactions 235 Notes 236 INTRODUCTION On December 1, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet made a hastily planned, clandestine trip to Pakistan. Tenet arrived in Islamabad deeply shaken by the news that less than three months earlier—just weeks before the attacks of September 11, 2001—al-Qa‘ida and Taliban leaders had met with two former Pakistani nuclear weapon scientists in a joint quest to acquire nuclear weapons. Captured documents the scientists abandoned as 193 AU6964.indb 193 12/16/08 5:44:39 PM 194 Charles P. Blair they fled Kabul from advancing anti-Taliban forces were evidence, in the minds of top U.S. -

CHEMICAL and BIOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS of JIHADI TERRORISM Animesh Roul

P a g e | 0 SSPC RESEARCH PAPER February 2016 APOCALYPTIC TERROR: CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS OF JIHADI TERRORISM Animesh Roul The threat of chemical and biological terrorism emanating from non-state actors, including the Islamic Jihadi organisations, which control large swathes of territories and resources, remains a major concern for nation states today. Over the years, the capability and intentions of Islamic jihadist groups have changed. They evidently prefer for more destructive and spectacular methods. This can be very well argued that if these weapons systems, materials or technologies were made available to them, they probably would use it against their enemy to maximize the impact and fear factor. Even though no terrorist group, including the Al Qaeda, so far has achieved success in employing these destructive and disruptive weapons systems or materials, in reality, various terrorist groups have been seeking to acquire WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction/Disruption) materials and its know-how. Apocalyptic Terror: Chemical and Biological Dimensions of Jihadi Terrorism The threat of chemical and biological terrorism emanating from non-state actors, including the Islamic Jihadi organisations, which control large swathes of territories and resources, remains a major concern for nation states today. Historically, no organised terrorist groups have perpetrated violent attacks using biological or chemical agents so far. Over the years, the capability and intentions of Islamic jihadist groups have changed. They are evidently preferring for more destructive and spectacular methods. This can be very well argued that if these weapons systems, materials or technologies were made available to them, they probably would use it against their enemy to maximize the impact and fear factor. -

High-Threat Chemical Agents: Characteristics, Effects, and Policy Implications

Order Code RL31861 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web High-Threat Chemical Agents: Characteristics, Effects, and Policy Implications Updated September 9, 2003 Dana A. Shea Analyst in Science and Technology Policy Resources, Science, and Industry Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress High-Threat Chemical Agents: Characteristics, Effects, and Policy Implications Summary Terrorist use of chemical agents has been a noted concern, highlighted after the Tokyo Sarin gas attacks of 1995. The events of September 11, 2001, increased Congressional attention towards reducing the vulnerability of the United States to such attacks. High-threat chemical agents, which include chemical weapons and some toxic industrial chemicals, are normally organized by military planners into four groups: nerve agents, blister agents, choking agents, and blood agents. While the relative military threat posed by the various chemical types has varied over time, use of these chemicals against civilian targets is viewed as a low probability, high consequence event. High-threat chemical agents, depending on the type of agent used, cause a variety of symptoms in their victims. Some cause death by interfering with the nervous system. Some inhibit breathing and lead to asphyxiation. Others have caustic effects on contact. As a result, chemical attack treatment may be complicated by the need to identify at least the type of chemical used. Differences in treatment protocols for the various high-threat agents may also strain the resources of the public health system, especially in the case of mass casualties. Additionally, chemical agents trapped on the body or clothes of victims may place first responders and medical professionals at risk. -

How States Respond to Terrorist Attacks: an Analysis of the Variance in Responses

How States Respond to Terrorist Attacks: An Analysis of the Variance in Responses A Thesis Submitted to The University of Michigan In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Bachelor of Arts Department of Political Science Lauren A Bondarenko March 2014 Advisor: Allan Stam Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………… i Acronyms/Abbreviations………………………………………………………………………………... ii Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 1: Introduction Conceptualizations………………………………………………………………………………. 4 National Security…………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Terrorism……………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Institutions……………………………………………………………………………………... 8 National Security as a Collective Action Problem……………………………… 11 American Institutional Reform………………………………………………………… 12 European Institutional Reform………………………………………………………… 15 Applying the Balance of Threat Theory…………………………………………….. 18 What the Literature is Missing…………………………………………………………. 21 Hypotheses…………………………………………………………………………………………... 22 Chapter Previews…………………………………………………………………………………. 23 Chapter 2: Methodology Use of the Global Terrorism Database…………………………………………………… 25 Reason for Database Selection…………………………………………………………. 25 Information Missing in the Database………………………………………………... 25 Creation of My Dataset…………………………………………………………………………. 27 Using GTD………………………………………………………………………………………. 27 Coding System………………………………………………………………………………… 28 Case Selection……………………………………………………………………………………… 29 A Note on Style……………………………………………………………………………………. -

Ayman Al-Zawahiri: the Ideologue of Modern Islamic Militancy

Ayman Al-Zawahiri: The Ideologue of Modern Islamic Militancy Lieutenant Commander Youssef H. Aboul-Enein, USN US Air Force Counterproliferation Center 21 Future Warfare Series No. 21 AYMAN AL-ZAWAHIRI: THE IDEOLOGUE OF MODERN ISLAMIC MILITANCY by Youssef H. Aboul-Enein The Counterproliferation Papers Future Warfare Series No. 21 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Ayman Al-Zawahiri: The Ideologue of Modern Islamic Militancy Youssef H. Aboul-Enein March 2004 The Counterproliferation Papers Series was established by the USAF Counterproliferation Center to provide information and analysis to assist the understanding of the U.S. national security policy-makers and USAF officers to help them better prepare to counter the threat from weapons of mass destruction. Copies of No. 21 and previous papers in this series are available from the USAF Counterproliferation Center, 325 Chennault Circle, Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6427. The fax number is (334) 953- 7530; phone (334) 953-7538. Counterproliferation Paper No. 21 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The Internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Author.................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgments .................................................................................... -

1. (SINF) Personal Information

SECRET 20310421 DEPARTMENTOF DEFENSE JOINTTASKFORCEGUANTANAMO GUANTANAMOBAY, CUBA APO AE 09360 JTF GTMO - CC 21 April MEMORANDUM FOR Commander, United States Southern Command, 3511 NW Avenue, Miami, FL 33172. SUBJECT: Recommendationfor ContinuedDetention Control(CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: 000121DP(S) JTF GTMO DetaineeAssessment 1. ( SINF) Personal Information : JDIMS/NDRC Reference Name: Salman S Mohammed Aliases and Current/ True Name: Sulayman Muhammad Awshan Al-Khalidi, Hussam Akida Place of Birth: Riyadh, SaudiArabia (SA) Dateof Birth: 14 January 1982 Citizenship: SaudiArabia InternmentSerial Number(ISN) : - 000121DP 2. (FOUO) Health: Detaineeis in good health. He sustained a gunshot wound to his right thigh prior to detainment. He has a history of myopia and astigmatism . He went on a hunger strike once in July 2005. He has a history of intermittent abdominalpain. 3. (SI/ NF) JTF GTMOAssessment: a . (S ) Recommendation: JTF GTMO recommendsthis detainee for Continued DetentionUnder Control (CD) . JTF GTMO previously assessed detainee as Retain in Control ( ) on 15 August 2005. b . ( SI Executive Summary: Detaineeis assessed to be a member ofAl-Qaida who traveled to Afghanistan to participate injihad. Detainee is on the Saudi MinistryofInterior General DirectorateofInvestigations (Mabahith) list ofhigh prioritydetainees. Detainee probablyparticipatedin hostilities against US and coalition forces as a member ofthe 55th CLASSIFIEDBY: MULTIPLESOURCES REASON: E.O. 12958SECTION1.5(C ) DECLASSIFYON: 20310421 SECRETI 20310421 SECRET // 20310421 JTF GTMO -CC SUBJECT : Recommendation for Continued Detention Under Control ( CD) for Guantanamo Detainee , ISN: 000121DP ( S ) Arab Brigade. He has strong familial ties to Al-Qaida . A variation of detainee’s alias appears on an Al-Qaida associated document Detainee was identified by known and assessed Al-Qaida members and admitted to residing in Taliban guesthouses.