Reading Group Guide Spotlight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Refugee Book Reading Campaign 2019 - Adult Booklist

Refugee Book Reading Campaign 2019 - Adult Booklist Read a Book About Refugees There is a great variety of books written about refugees - including award-winning fiction – and books by refugees themselves. Why not borrow one of these from your local library or buy one from your local book shop? Do you have a book club? Maybe you would consider adding one of these titles to the reading list. Fiction Sea Prayer Author: Khaled Hosseini, Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London A heart-wrenching story about a refugee family from the international bestselling author of The Kite Runner. “A truly gifted teller of tales … he's not afraid to pull every string in your heart to make it sing” – The Times Deep Sea Author: Annika Thor, Publisher: Delacorte Press. Readers of Anne of Green Gables and Hattie Ever After will love following Stephie’s story, which takes place during World War II and began with A Faraway Island and continued with The Lily Pond. Three years ago, Stephie and her younger sister, Nellie, escaped the Nazis in Vienna and fled to an island in Sweden, where they were taken in by different families. Now sixteen-year-old Stephie is going to school on the mainland. Stephie enjoys her studies, and rooming with her school friend, May. But life is only getting more complicated as she gets older. Stephie might lose the grant money that is funding her education. Her old friend Verra is growing up too fast. And back on the island, Nellie wants to be adopted by her foster family. Stephie, on the other hand, can’t stop thinking about her parents, who are in a Nazi camp in Austria. -

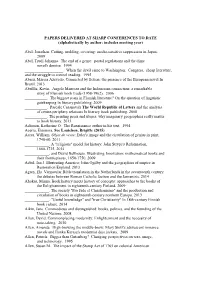

PAPERS DELIVERED at SHARP CONFERENCES to DATE (Alphabetically by Author; Includes Meeting Year)

PAPERS DELIVERED AT SHARP CONFERENCES TO DATE (alphabetically by author; includes meeting year) Abel, Jonathan. Cutting, molding, covering: media-sensitive suppression in Japan. 2009 Abel, Trudi Johanna. The end of a genre: postal regulations and the dime novel's demise. 1994 ___________________. When the devil came to Washington: Congress, cheap literature, and the struggle to control reading. 1995 Abreu, Márcia Azevedo. Connected by fiction: the presence of the European novel In Brazil. 2013 Absillis, Kevin. Angele Manteau and the Indonesian connection: a remarkable story of Flemish book trade (1958-1962). 2006 ___________. The biggest scam in Flemish literature? On the question of linguistic gatekeeping In literary publishing. 2009 ___________. Pascale Casanova's The World Republic of Letters and the analysis of centre-periphery relations In literary book publishing. 2008 ___________. The printing press and utopia: why imaginary geographies really matter to book history. 2013 Acheson, Katherine O. The Renaissance author in his text. 1994 Acerra, Eleonora. See Louichon, Brigitte (2015) Acres, William. Objet de vertu: Euler's image and the circulation of genius in print, 1740-60. 2011 ____________. A "religious" model for history: John Strype's Reformation, 1660-1735. 2014 ____________, and David Bellhouse. Illustrating Innovation: mathematical books and their frontispieces, 1650-1750. 2009 Aebel, Ian J. Illustrating America: John Ogilby and the geographies of empire in Restoration England. 2013 Agten, Els. Vernacular Bible translation in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century: the debates between Roman Catholic faction and the Jansenists. 2014 Ahokas, Minna. Book history meets history of concepts: approaches to the books of the Enlightenment in eighteenth-century Finland. -

Download Kindle \\ A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10

BJYSTRYBPPRS > Kindle A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10 A .L.A . Booklist V olume 10 Filesize: 9.13 MB Reviews This sort of pdf is everything and made me searching forward plus more. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. You may like just how the author compose this book. (Mae Jones) DISCLAIMER | DMCA B0HR27CK5I4I / PDF » A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10 A.L.A. BOOKLIST VOLUME 10 Not Avail, United States, 2012. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 246 x 189 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can download a free scanned copy of the original book (without typos) from the publisher. Not indexed. Not illustrated. 1914 Excerpt: .and to the general reader. Bibliographies (7p.) arranged according to the various writers. 804 Literature. Analytics for authors (6 cards) and bibliography 131449/10 Bullard, Arthur. The Barbary coast, by Albert Edwards. N. Y. Macmillan (S) 1913. 312p. illus. $2 net. Fieen graphic travel sketches of French North Africa, all but three written for the Outlook during the last twelve years. Besides the vivid reproduction of the physical aspects and atmosphere, the author gives interesting glimpses of the thoughts and philosophy of his eastern friends. The spirit of the region he has seized and given to us with charm and humor. 916.1 Barbary states Africa, North 13- 20787/4 Burgess, Thomas. Greeks in America. Bost.Sherman, French(0)1913. 256p. illus. $1.35 net. Discusses from the Greek s standpoint the early exodus from the mother country, the hardships, and later immigration from 1891 to 1913; the industrial, social and religious life here; and the character of communities in a number of cities. -

Incorporating Bibliotherapy Into the Classroom: a Handbook for Educators Melissa Mcencroe Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Fall 2007 Incorporating Bibliotherapy Into the Classroom: a Handbook for Educators Melissa McEncroe Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation McEncroe, Melissa, "Incorporating Bibliotherapy Into the Classroom: a Handbook for Educators" (2007). All Regis University Theses. 74. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/74 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University College for Professional Studies Graduate Programs Final Project/Thesis Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

Censorship!Censorship!

CENSORSHIP!CENSORSHIP! LDF BANNED CB K HAN BOO EE FiGhT fOr tHeD B K W FrEeDoM tO rEaD! OOK S STAFF DIRECTOR’S NOTE Charles Brownstein, Executive Director Alex Cox, Deputy Director Samantha Johns, Development Manager Happy Banned Books Week! Every year, communities come together in Kate Jones, Office Manager this national celebration of the freedom to read! This year, Banned Books Betsy Gomez, Editorial Director Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Week spotlights young adult books, which is by far the category most Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor commonly targeted for censorship. Stand up for the right to read for all Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers by becoming a part of the Banned Books Week celebration that will take place September 27 through October 3, 2015! BOARD OF DIRECTORS Larry Marder, President Milton Griepp, Vice President Launched in 1982 to draw attention to the problem of book censorship Jeff Abraham, Treasurer in the United States, Banned Books Week is held during the last week of Dale Cendali, Secretary Jennifer L. Holm September. By being a part of it, you can make a difference in protecting Reginald Hudlin the freedom to read! Katherine Keller Paul Levitz In this handbook, Comic Book Legal Defense Fund provides you with Christina Merkler Chris Powell all the tools you need to prepare your Banned Books Week celebration. Jeff Smith We’ll talk about how books are banned, show you some specific cases ADVISORY BOARD in which comics were challenged, and provide you with hands on tips to Neil Gaiman & Denis Kitchen, Co-Chairs celebrate Banned Books Week in your community. -

Leveled Book List for Home Reading

Looking for Book Ideas in Your “Just Right” Level? Booklist for 3-4 Classroom by Guided Reading Level Michelle, Alli, Cory Enclosed is a list of some great books for your children. The Guided Reading Level is the leveling system we currently use K6 at ACS to help children find “just right” / “good fit” books. Most of student’s reading should be within levels s/he control with accuracy, fluency, and comprehension (see comprehension link in our blog). 3rd Grade M Q 4th Grade Q S/T 5th Grade T V Guided Reading Level L DRA 24 Cam Jansen series by David Adler Horrible Harry series by Suzy Kline Pinky and Rex by James Howe Ricky Ricotta’s Mighty Robot series by Dav Pilkey Song Lee series by Suzy Kline Guided Reading Level M DRA 28 Bailey School Kids series by Debbie Dadey Bink and Gollie by Kate DiCamillo Blue Ribbon Blues by Jerry Spinelli Buddy: the First Seeing Eye Dog by Eva Moore Camp Sink or Swim by Gibbs Davis The Case of the Elevator Duck by Polly Brends The Chalk Box Kid by Clyde Bulla Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs by Judi Barrett The Copper Lady by Alice and Kent Ross The Drinking Gourd by Ferdinand Monjo Everybody Cooks Rice by Norah Dooley Five True Dog Stories by Margaret Davidson Five True Horse Stories by Margaret Davidson Flat Stanley by Jeff Brown The Flying Beaver Brothers series by Maxwell Eaton Freckle Juice by Judy Blume The Ghost in Tent 19 by Jim and Jane O’Connor The Haunted Library by Dori Hilestad Butler Helen Keller by Margaret Davidson Ivy and Bean by Annie Barrows Jenny Archer series by Ellen Conford Judy Moody series Megan McDonald Junie B. -

Indiana History: a Booklist for Fourth Grade

Volume 8, Number 2 (1989) /53 Indiana History: A Booklist for Fourth Grade Winnie Adler and Dianne Lawson, Youth Librarians Tippecanoe County Public Library Lafayette, IN Presenting our Hoosier heritage to connections, and other works which Indiana youngsters is a joy that have chapters on Eastern Woodland parents, teachers and librarians or Indiana Indians. Only four Lincoln share. Unfortunately, although biographies are cited in the "Famous Indiana history is studied in fourth People" section although there are grade, many of the materials that others which are appropriate. would be useful to youthful research ers are at a much higher level. To General Works help meet the demand for lower level Indiana history materials, our youth • Bailey, Bernardine. Picture Book staff reviewed our collection and Of Indiana. Albert Whitman, 1966. created a topical list to guide students. • Britannica Junior. Encyclopedia Of course this booklist is based Britannica, Inc., 1976. chiefly on our own collection and • Crout, George. Where The although we have consistently sought Ohio Flows. Benefic Press, 1964. elementary-level Indiana materials, you may well own titles which we • Crump, Claudia. Indiana Yester lack. We hope this booklist will help day and Today. Silver Burdett, 1985. you as we all try to share the good • Fradin, Dennis B. Indiana In news about Indiana's past. Words and Pictures. Children's, 1980. The topical non-fiction list is not • McCall, Edith. Forts In The annotated as most of the titles are self Wilderness. Children's, 1980. expanatory. The six categories are based on subjects suggested by a • Peek, David T. Indiana Adven- fourth grade teacher and our experi ture. -

Bibliotherapy Intervention Exposure and Level of Emotional Awareness Among Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2010 Bibliotherapy Intervention Exposure and Level of Emotional Awareness Among Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Elaine Harper Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the Education Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Harper, Elaine, "Bibliotherapy Intervention Exposure and Level of Emotional Awareness Among Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders" (2010). ETD Archive. 125. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/125 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIBLIOTHERAPY INTERVENTION EXPOSURE AND LEVEL OF EMOTIONAL AWARENESS AMONG STUDENTS WITH EMOTIONAL AND BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS ELAINE HARPER Bachelor of Arts, Psychology Case Western Reserve University August 1989 Master of Education, Severe Behavior Disorders Kent State University August 1993 Submitted in partial fulfillment for requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN URBAN EDUCATION: LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 This dissertation has been approved for The Office of Doctoral Studies, College of Education and the College of Graduate Studies by ________________________________________________________________ -

Fall 2020 Textbooks

Fall 2020 Textbooks Course Req or Pub Course Title ISBN-13 Title Author Edition Publisher ID Rec Price AC 101 Acupuncture Channels 978- Chinese Acupuncture and Cheng 3rd, 2010 Foreign Required $165 Pelzer and Points I 7119059945 Moxibustion (CAM) Language Press AC 101 Acupuncture Channels 978- Acupuncture A Comprehensive Bensky 1981 Eastland Required $75 Pelzer and Points I 0939616008 Text (Shanghai College of Press Traditional Medicine) AC 101 Acupuncture Channels 978- Manual of Acupuncture, A Deadman 2nd 2007 Eastland Required $150 Pelzer and Points I 0951054659 Press AC 101 Acupuncture Channels 978- Foundations of Chinese Maciocia 3rd, 2015 Churchill Required $175 Pelzer and Points I 0702052163 Medicine, The Livingston e AC 102 Acupuncture Channels 978- Chinese Acupuncture and Cheng 3rd, 2010 Foreign Required $165 Pelzer and Points II 7119059945 Moxibustion (CAM) Language Press AC 102 Acupuncture Channels 978- Acupuncture A Comprehensive Bensky 1981 Eastland Required $75 Pelzer and Points II 0939616008 Text (Shanghai College of Press Traditional Medicine) AC 102 Acupuncture Channels 978- Manual of Acupuncture, A Deadman 2nd 2007 Eastland Required $150 Pelzer and Points II 0951054659 Press AC 102 Acupuncture Channels 978- Foundations of Chinese Maciocia 3rd, 2015 Churchill Required $175 Pelzer and Points II 0702052163 Medicine, The Livingston e 1 6/22/2020 Fall 2020 Textbooks AC 104 Acupuncture Channels 978- Chinese Acupuncture and Cheng 3rd, 2010 Foreign Required $165 Pelzer and Points IV 7119059945 Moxibustion (CAM) Language Press -

Anuscripts on My Mind

anuscripts on my mind News from the No. 23 January 2018 ❧ Editor’s Remarks ❧ Exhibitions ❧ Queries and Musings ❧ Conferences and Symposia ❧ New Publications, etc. ❧ Editor’s Remarks ear colleagues and manuscript lovers: My best Greetings and Happy 2018! I begin this issue with Da question to all paleographers and codicologists who may chance to read it: in your opinion, how con- temporary with the manuscript itself is the mend and text replacement on the image at right? Would it coin- cide with the addition of the gloss? How skillful is/are the scribe(s) who have imitated the gloss script in the lower portion of the mend; were the replacement let- ters done by the original gloss scribe, or by a later indi- vidual? Did the tear that occasioned the repair occur at the time the gloss was being written? I am trying to un- derstand the medieval criteria for making repairs. It is in- teresting that the repairer restored not only a tie mark for the gloss, but also the decorative bracket alongside 6 lines of gloss text in the lower righthand gloss column. Have you any ideas, observations, or technical input? Is there any bibliography on medieval repair practices for Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2109, fol. 30r the manuscript page? Please send me thoughts or infor- Justinian, Institutes mation you might have by email: [email protected] The deadline for submission of proposals to the Sixth Annual Symposium on Medieval and Renaissance Stud- ies, June 18–20, 2018, at Saint Louis University has been extended to the end of January, as has the deadline for the 45th Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies that will take place within it. -

Wellbeing Collection Booklist Final 11/1/10 10:29 Page 1

Wellbeing Collection Booklist final 11/1/10 10:29 Page 1 The Wellbeing Collection ... Contact Details Address Bibliotherapy Service The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Brompton Library Adult Wellbeing Collection 210 Old Brompton Road London SW5 0BS Booklist Phone 020 7341 0729 Email [email protected] Website www.rbkc.gov.uk/libraries/bibliotherapy Wellbeing Collection Booklist final 11/1/10 10:05 Page 3 Wellbeing Collection booklist Adults What is the Wellbeing Collection? What if the book is unavailable? The Wellbeing Collection is a range of good quality self-help books which Each library has one or more copies of most books on the Wellbeing can help people understand and cope with common mental health Collection booklist. If the book you want is out on loan, a copy will problems. Using books in this way can provide people with guidance and be reserved for you free of charge and the library will let you know when support to overcome a range of emotional and psychological issues. it arrives. How does it work? How long can I borrow the book for? You can either choose a book yourself, or a health professional can A book can be borrowed for three weeks and renewed a further recommend one for you from the Wellbeing Collection booklist. four times. The complete booklist is available at the library or online at www.rbkc.gov.uk/libraries/bibliotherapy Is the service confidential? Most of the books on the Wellbeing Collection booklist are available Yes, library staff will not divulge any information about who borrowed the from any Kensington and Chelsea Library. -

FIU Law Spring 2021 Booklist Master

CAUTION: Yellow Highlight = Pending Adoption Update; List will be updated as provided by NOTES: Professor and/or Publisher. FIU LAW SPRING 2021 BOOKLIST Green Highlight = FIU Law Library, use URL provided to access Book Format = Professor’s approved format; students may use/purchase print if preferred; if not provided, print is default, see Notes for details. Blue Highlight = West Academic ebook Discount Available, see https://libanswers.law.fiu.edu/ faq/313135 Professor Class LAW # Sec ISBN eBook ISBN Book Format Title Author Publisher Edition Adoption Type Source Notes ebook discount available from West Academic, registration required through West Academic Assessment, see West Academic ebook instructions FAQ at https://libanswers.law.fiu.edu/faq/313135 eBook URL to verify your selection, not to purchase, is https://www.westacademic.com/Barrett-and- Matthew J. Barrett, Herwitzs-Accounting-for-Lawyers-Concise-5th- HESCH Accounting For Lawyers LAW 6760 U01 9781599416724 9781634598538 Any Accounting for Lawyers, Concise David R. Herwitz West Academic 5th Required Purchase 9781634598538 Bargaining for Advantage: Negotiation KLEIN ADR LAW 6310 U01 9780143036975 Any Strategies for Reasonable People G. Richard Shell Penguin Books 2nd Required Purchase No format preference. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Roger Fisher, KLEIN ADR LAW 6310 U01 9781844131464 Any Without Giving In William L. Ury Penguin Books 3rd Revised Ed. Required Purchase No format preference. Marilyn J. Berger, Trial Advocacy: Planning, Analysis, and John B. Mitchell, SMITH Advanced Trial Advocacy LAW 7364 U01 9781454841531 Any Strategy Ronald H. Clark Wolters Kluwer 4th Required Purchase No format preference. ebook from FIU Law Library via ProView at https://proview.thomsonreuters.com/launch app/title/uscl/an/fltrob/v1/document/Front SMITH Advanced Trial Advocacy LAW 7364 U01 9780314612274 9780314838483 Any Florida Trial Objections Charles W.