Nomination Form, N.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Park Sites of the George Washington Memorial Parkway

National Park Service Park News and Events U.S. Department of the Interior Virginia, Maryland and Potomac Gorge Bulletin Washington, D.C. Fall and Winter 2017 - 2018 The official newspaper of the George Washington Memorial Parkway Edition George Washington Memorial Parkway Visitor Guide Drive. Play. Learn. www.nps.gov/gwmp What’s Inside: National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior For Your Information ..................................................................3 George Washington Important Phone Numbers .........................................................3 Memorial Parkway Become a Volunteer .....................................................................3 Park Offices Sites of George Washington Memorial Parkway ..................... 4–7 Alex Romero, Superintendent Partners and Concessionaires ............................................... 8–10 Blanca Alvarez Stransky, Deputy Superintendent Articles .................................................................................11–12 Aaron LaRocca, Events ........................................................................................13 Chief of Staff Ruben Rodriguez, Park Map .............................................................................. 14-15 Safety Officer Specialist Activities at Your Fingertips ...................................................... 16 Mark Maloy, Visual Information Specialist Dawn Phillips, Administrative Officer Message from the Office of the Superintendent Jason Newman, Chief of Lands, Planning and Dear Park Visitors, -

Netherlands Carillon Rehabilitation

Delegated Action of the Executive Director PROJECT NCPC FILE NUMBER Netherlands Carillon Rehabilitation 7969 Arlington Ridge Park Arlington, Virginia NCPC MAP FILE NUMBER 1.61(73.10)44718 SUBMITTED BY United States Department of the Interior ACTION TAKEN National Park Service Approve as requested REVIEW AUTHORITY Advisory Per 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) The National Park Service (NPS) has submitted for Commission review site and building plans for the Netherlands Carillon in Arlington Ridge Park in Arlington, Virginia. The Netherlands Carillon is a 127-foot-tall open steel historic structure that sits within Arlington Ridge Park, near the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery. It was a gift from the people of the Netherlands to the people of the United States in gratitude for American aid during and after World War II, and symbolizes friendship between the two countries, and their common allegiance to the principles of freedom, justice, and democracy. The carillon is cast from a bronze alloy and features 50 bells, each carrying an emblem and verse representing a group within Dutch society. The original gift of the bells was conceived in 1950, which were completed and shipped to the United States in 1954 and hung in a temporary structure in West Potomac Park. The current structure was constructed in 1960 by Dutch architect Joost W.C. Boks, and is recognized as one of the first modernist monuments constructed in the region. The structure sits within a square plaza, and is flanked by two bronze lion sculptures. To the east of the plaza is a tulip library, also a gift from the Dutch, which was planted in 1964. -

Texas Iwo Jima Letter Jima Iwo Texas

Texas Iwo Jima Letter A new focus on the Texas Iwo Jima Memorial Our country’s most iconic Military Memorial shall deserve in some small measure the sits in the Mexican border town of Harlingen, sacrifices they made and that our efforts will be Iwo Jima Texas. By God’s Grace, via five heroic Marines, worthy of theirs. This Monument is to recognize “Uncommon Valor and one heroic Corpsman; combat photographer that the Marines ...and those who have fallen are Was A Common Joe Rosenthal and Sculptor Felix De Weldon; the remembered here as Citizens as well as fighting Virtue” original Iwo Jima Flag Raising Memorial hallows men. Citizens who sacrificed their lives for what the ground here on the campus of the Marine they believed was the Common Good.” Admiral Chester Nimitz Military Academy (MMA). That is the purpose of this newsletter, to This place of goosebumps hope we are worthy of the and eyemist, is a colossal sacrifices the Marines made on “The Iwo Jima victory came reminder of the Virtuous Iwo Jima for us. We want to call at a terrible price. By the Solidarity of men so close they attention to this Memorial which time the American troops are willing to die for one means so much to man’s good had taken the entire island, another. nature and our Common Good. over 17,000 Marines were The Memorial was dedicated The Marine Military Academy is wounded and more than here on April 16, 1982, a long led by USMC COL Glenn Hill, his 5,000 Marines and 1,200 way from Feb. -

Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 the Bottom Line C-3

INSIDE National Anthem A-2 2/3 Air Drop A-3 Recruiting Duty A-6 Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 The Bottom Line C-3 High School Cadets D-1 MVMOLUME 35, NUMBER 8 ARINEARINEWWW.MCBH.USMC.MIL FEBRUARY 25, 2005 3/3 helps secure clinic Marines maintain security, enable Afghan citizens to receive medical treatment Capt. Juanita Chang Combined Joint Task Force 76 KHOST PROVINCE, Afghanistan — Nearly 1,000 people came to Khilbasat village to see if the announcements they heard over a loud speaker were true. They heard broadcasts that coalition forces would be providing free medical care for local residents. Neither they, nor some of the coalition soldiers, could believe what they saw. “The people are really happy that Americans are here today,” said a local boy in broken English, talking from over a stone wall to a Marine who was pulling guard duty. “I am from a third-world country, but this was very shocking for me to see,” said Spc. Thia T. Valenzuela, who moved to the United States from Guyana in 2001, joined the United States Army the same year, and now calls Decatur, Ga., home. “While I was de-worming them I was looking at their teeth. They were all rotten and so unhealthy,” said Valenzuela, a dental assistant from Company C, 725th Main Support Battalion stationed out of Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. “It was so shocking to see all the children not wearing shoes,” Valenzuela said, this being her first time out of the secure military facility, or “outside the wire” as service members in Afghanistan refer to it. -

The Judge Advocate Journal, Bulletin No. 31, January, 1961

Bulletin No. 31 .January, 1961 The Judge Advocate PR R F THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL LIBRARY Published By JUDGE ADVOCATES ASSOCIATION An affiliated organization of the American Bar Association, composed of lawyers of all components of the Army, Navy, and Air Force Denrike Building Washington 5, D. C. JUDGE ADVOCATES ASSOCIATION Officers for 1960-61 REGINALD c. HARMON, Virginia..........................................................Pl'C$ident ERNEST M. BRANNON, District of Columbia................ Pirst Vice Pnsident FREDERICK R. BOLTON, Michigan ................................ Second Vice Preside11t PENROSE L. ALBRIGHT, Virginia.... ..... ..................................... .Secretary CLIFFORD A. SHELDON, District of Columbia ............................... .. Trerrnurer JOHN RITCHIE, III, Illinois .......................... ........................Dele[!Clte to AB,1 Directors Joseph A. Avery, Va.; Franklin H. Berry, N. J.; Robert G. Burke, N. Y.; Perry H. Burnham, Colo.; Charles L. Decker, D C.; John H. Finger, Calif.; Robert A. Fitch, Va.; Osmer C. Fitts, Vt.; James Gar nett, Va.; George W. Hickman, Calif.; J. Fielding Jones, Va.; Stanley 'iV. Jones, Va.; Herbert M. Kidner, Pa.; Thomas H. King, Md.; Albert M. Kuhfeld, Va.; William C. Mott, Md.; Joseph F. O'Connell, Mass.; Alexander Pirnie, N. Y.; Gordon Simpson, Texas; Clio E. Straight, Va.; Moody R. Tid\Yell, Va.; Fred Wade, Pa.; Ralph W. Yarborough, Texas. Executive Secretary and Editor RICHARD H. LOVE Washington, D. C. Bulletin No. 31 January, 1961 Publication Notice The views expressed in articles printed herein are not to be regarded as those of the Judge Advocates Association or its officers and directors or of the editor unless expressly so stated. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE The Federal Legislative Process.............................................................. 1 The 1960 Annual Meeting........................................................................ 35 Limitation of Settlements Under FTCA............................................. -

History of Roads in Fairfax County, Virginia from 1608

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. A HISTORY OF ROADS IN FAIRFAX COUNTY, VIRGINIA: 1608-1840 by Heather K. Crowl submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Anthropology Chair: Richard J. -

Figure 1) Topographic Map, Arlington Ridge Area

....... County Une Parks -Arlington Ridge Boundary 1 inch: 900 feel l!Jppt~ll'Olt'd~tAd.,glQo!Cfll'li!)'G,l!;M1N)i'lgC.~ ~d~d..,d,QJ\llf~ •50 000 Feo1 C.f'CKI 14 •I $1•~•rlnjjlt.nv.11& l0<s.pa~•I JGkl!CnN "°~' Internet, see footnote 1 Figure 1) Topographic Map, Arlington Ridge Area 34 ARLINGTON H ISTORICAL M AGAZINE On the Street Where You Live: Arlington Ridge, Virginia BY MARTY SUYDAM What's in a name of a place? How did that name get decided? Whose life is now memorialized? The story of the names of places can represent a fascinating tale about the place where we live, yet often, know little about. We live in an area named Arlington Ridge, a topographic "finger" that points to Arlington House, the Lee mansion in Arlington Cemetery, through the area of the Pentagon. In the 1800's Anthony Fraser and James Roach owned the properties. Today, the following streets, clockwise from the north, bound the area: S. Joyce St, S. Glebe Road, and Army Navy Drive. Parts of the area have been known as: Green Valley, Club Manor Estates, Aurora Hills, Virginia Highlands, and Aurora Highlands. Most of the paved roadways in the immediate surroundings of South Nash Street are less than 100 years old. Though some roads date back to the Revolu tion, most have new names. 1 So, what is the name evolution on Arlington Ridge? The area was once part of the 1,000-acre estate of Anthony Fraser. The area was known as Green Valley, likely named for James Green, who lived on the land near the present location of the clubhouse at Army Navy Country Club. -

Directory Carillons

Directory of Carillons 2014 The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America Foreword This compilation, published annually by the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America (GCNA), includes cast-bell instruments in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The listings are alphabetized by state or province and municipality. Part I is a listing of carillons. Part II lists cast- bell instruments which are activated by a motorized mechanism where the performer uses an ivory keyboard similar to that of a piano or organ. Additional information on carillons and other bell instruments in North America may be found on the GCNA website, http://gcna.org, or the website of Carl Zimmerman, http://towerbells.org. The information and photos in this booklet are courtesy of the respective institutions, carillonneurs, and contact people, or available either in the public domain or under the Creative Commons License. To request printed copies or to submit updates and corrections, please contact Tiffany Ng ([email protected]). Directory entry format: City Name of carillon Name of building Name of place/institution Street/mailing address Date(s) of instrument completion/expansion: founder(s) (# of bells) Player’s name and contact information Contact person (if different from player) Website What is a Carillon? A carillon is a musical instrument consisting of at least two octaves of carillon bells arranged in chromatic series and played from a keyboard permitting control of expression through variation of touch. A carillon bell is a cast bronze cup-shaped bell whose partial tones are in such harmonious relationship to each other as to permit many such bells to be sounded together in varied chords with harmonious and concordant effect. -

1970 Catalog Number FEHA 1924

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Finding Aid Federal Hall Memorial Associates Administrative Records, 1804 - 1970 Catalog Number FEHA 1924 National Park Service Manhattan Sites Federal Hall National Memorial Rachel M. Oleaga October 2012 This finding aid may be accessed electronically from the National Park Service Manhattan Historic Sites Archive http://www.mhsarchive.org Processing was funded by a generous donation from the Leon Levy Foundation to the National Parks of New York Harbor Conservancy. Finding Aid Federal Hall Memorial Associates Administrative Records – Catalog Number FEHA 1924 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS ................................................................................................................... 4 PROVENANCE NOTE ...................................................................................................................................... 5 HISTORICAL NOTE ......................................................................................................................................... 6 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ....................................................................................................................... 10 ARRANGEMENT NOTE ................................................................................................................................. 10 SERIES -

I.S. Antarctic Projects Officer

I.S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER VOLUME III NUMBER :J DECEMBER 1961 [December 14, 19111. At three in the afternoon a simultaneous "Flt" rang out from the drivers. They had carefully examined their sledge-meters, and they all showed the full distance -- our Pole by reckoning. The goal was reached, the journey ended. Roald Amundsen, The South Pole, vol. II, p. 121. Thursday, December 14 (1911]. However, we all lunched together after a satisfactory mornings work. In the after- noon we did still better, and camped at 6.30 with a very marked change in the land bear- ings. We must have come 11 or 12 miles (stat.). We got fearfully hot on the march, sweated through everything and stripped off jerseys. The result is we are pretty cold and clammy now, but escape from the soft snow and a good march compensate every discomfort. Captain Robert F. Scott, Scotts Last Expedition, arranged by Leonard Huxley, vol. I, p. 346. Volume III, No. 4 December 1961 CONTENTS The Month in Review 1 Ellsworth Land Traverse 1 Topo South Completed 3 Sky-Hi Station Established 4 Ninth Troop Carrier Squadron Commended 5 Note Recovered 6 Overland Expeditions to the South Pole (1910-1961) 7 Tribute to an Explorer, by James E. Mooney 11 The Hydrographic Office in the Antarctic 13 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 14 Antarctic Visitors 16 Official Foreign Representative Exchange Program 18 Material for this issue of the Bulletin was adapted from press releases issued by the Department of Defense and the National Sci- enoe Foundation and from incoming dispatches. -

A History of Residential Development, Planning, and Zoning in Arlington County, Virginia

A History of Residential Development, Planning, and Zoning in Arlington County, Virginia April 2020 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the guidance and feedback from Arlington County staff, including Mr. Russell Danao-Schroeder, Ms. Kellie Brown, Mr. Timothy Murphy, and Mr. Richard Tucker. We appreciate your time and insights. Prepared by Dr. Shelley Mastran Jennifer Burch Melissa Cameron Randy Cole Maggie Cooper Andrew De Luca Jose Delcid Dinah Girma Owain James Lynda Ramirez-Blust Noah Solomon Alex Wilkerson Madeline Youngren Cover Image Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/arlingtonva/29032004740/in/album-72157672142122411/ i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................................................ i Prepared by ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... i Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................................. ii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................................... iii Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

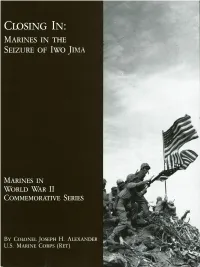

Closingin.Pdf

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead.