Scientific Exploration of Mars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selection of the Insight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript InSight Landing Site Paper v9 Rev.docx Click here to view linked References Selection of the InSight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N. Warner1,2, I. J. Daubar1, R. Fergason3, R. Kirk3, R. Beyer4, A. Huertas1, S. Piqueux1, N. E. Putzig5, B. A. Campbell6, G. A. Morgan6, C. Charalambous7, W. T. Pike7, K. Gwinner8, F. Calef1, D. Kass1, M. Mischna1, J. Ashley1, C. Bloom1,9, N. Wigton1,10, T. Hare3, C. Schwartz1, H. Gengl1, L. Redmond1,11, M. Trautman1,12, J. Sweeney2, C. Grima11, I. B. Smith5, E. Sklyanskiy1, M. Lisano1, J. Benardino1, S. Smrekar1, P. Lognonné13, W. B. Banerdt1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 2State University of New York at Geneseo, Department of Geological Sciences, 1 College Circle, Geneseo, NY 14454 3Astrogeology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001 4Sagan Center at the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 5Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302; Now at Planetary Science Institute, Lakewood, CO 80401 6Smithsonian Institution, NASM CEPS, 6th at Independence SW, Washington, DC, 20560 7Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College, South Kensington Campus, London 8German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planetary Research, 12489 Berlin, Germany 9Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA; Now at Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA 98926 10Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996 11Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 12MS GIS Program, University of Redlands, 1200 E. Colton Ave., Redlands, CA 92373-0999 13Institut Physique du Globe de Paris, Paris Cité, Université Paris Sorbonne, France Diderot Submitted to Space Science Reviews, Special InSight Issue v. -

Magnetic Planets and Magnetic Planets and How Mars Lost Its

Magnetic Planets and How Mars Lost Its Atmosphere Bob Lin Physics Department & Space Sciences Laboratory Universityyf of Calif ornia, Berkeley Also (visiting) School of Space Research Kyung Hee University, Korea Thanks to the MGS, MAVEN, and LP teams Earth’s Magnetic Field The Earth’s Magnetosphere Explorer 35 (1967) Lunar Shadowing Apollo 15 Mission -1971 Lunar Rover -> <- Jim Arnold's Gamma-ray Spectrometer <- Apollo 15 Subsatellite -> <= SIM (Scientific Instrument Module) Lunar Shadowing <= Downward electrons <= Upward electrons <= Ratio of Upward to DdltDownward electrons Electron Reflection Electron Trajectory Converging Magnetic Fields Secondary Electron ---- ---- - dv||RemotelydU SensingdB Surface MagneticB Fields by m + e + μ = 0⇒sin 2 α = LP []1- eΔU E Planetary Electron Reflection Magnetometryc (PERM) dt ds ds BSurf Apollo 15 & 16 Subsatellites Electron Reflectometry OneHowever, of the the great Apollo surprises 15 & 16 from Subsatellite Apollo was magnetic the discovery data set of paleomagneticis very sparse and fields confined in the lunar within crust 35 degrees. Their existence of the suggestsequator. Attempts that magnetic to correlate fields atsurface the Moon magnetic were muchfields with strongerspecific geologic in the past features than they were are largely today. unsuccessful. Mars Observer (1992-3) – disappeared 3 days before Mars orbit insertion Mars Global Surveyy(or (MGS) 1996-2006 MGS Mag/ER team Current state of knowledge • Very strong crustal fields measured from orbit: – Discovered by MGS: ~10 times stronger -

Oxygen Exosphere of Mars: Evidence from Pickup Ions Measured By

Oxygen Exosphere of Mars: Evidence from Pickup Ions Measured by MAVEN By Ali Rahmati Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Professor Thomas E. Cravens, Chair ________________________________ Professor Philip S. Baringer ________________________________ Professor David Braaten ________________________________ Professor Mikhail V. Medvedev ________________________________ Professor Stephen J. Sanders Date Defended: 22 January 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Ali Rahmati certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Oxygen Exosphere of Mars: Evidence from Pickup Ions Measured by MAVEN ________________________________ Professor Thomas E. Cravens, Chair Date approved: 22 January 2016 ii Abstract Mars possesses a hot oxygen exosphere that extends out to several Martian radii. The main source for populating this extended exosphere is the dissociative recombination of molecular oxygen ions with electrons in the Mars ionosphere. The dissociative recombination reaction creates two hot oxygen atoms that can gain energies above the escape energy at Mars and escape from the planet. Oxygen loss through this photochemical reaction is thought to be one of the main mechanisms of atmosphere escape at Mars, leading to the disappearance of water on the surface. In this work the hot oxygen exosphere of Mars is modeled using a two-stream/Liouville approach as well as a Monte-Carlo simulation. The modeled exosphere is used in a pickup ion simulation to predict the flux of energetic oxygen pickup ions at Mars. The pickup ions are created via ionization of neutral exospheric oxygen atoms through photo-ionization, charge exchange with solar wind protons, and electron impact ionization. -

The Reference Mission of the NASA Mars Exploration Study Team

NASA Special Publication 6107 Human Exploration of Mars: The Reference Mission of the NASA Mars Exploration Study Team Stephen J. Hoffman, Editor David I. Kaplan, Editor Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas July 1997 NASA Special Publication 6107 Human Exploration of Mars: The Reference Mission of the NASA Mars Exploration Study Team Stephen J. Hoffman, Editor Science Applications International Corporation Houston, Texas David I. Kaplan, Editor Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas July 1997 This publication is available from the NASA Center for AeroSpace Information, 800 Elkridge Landing Road, Linthicum Heights, MD 21090-2934 (301) 621-0390. Foreword Mars has long beckoned to humankind interest in this fellow traveler of the solar from its travels high in the night sky. The system, adding impetus for exploration. ancients assumed this rust-red wanderer was Over the past several years studies the god of war and christened it with the have been conducted on various approaches name we still use today. to exploring Earth’s sister planet Mars. Much Early explorers armed with newly has been learned, and each study brings us invented telescopes discovered that this closer to realizing the goal of sending humans planet exhibited seasonal changes in color, to conduct science on the Red Planet and was subjected to dust storms that encircled explore its mysteries. The approach described the globe, and may have even had channels in this publication represents a culmination of that crisscrossed its surface. these efforts but should not be considered the final solution. It is our intent that this Recent explorers, using robotic document serve as a reference from which we surrogates to extend their reach, have can continuously compare and contrast other discovered that Mars is even more complex new innovative approaches to achieve our and fascinating—a planet peppered with long-term goal. -

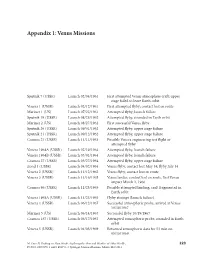

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization Clayton Knappenberger Depauw University

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2015 An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization Clayton Knappenberger DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Economics Commons, and the The unS and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Knappenberger, Clayton, "An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization" (2015). Student research. Paper 28. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization Clayton Knappenberger 2015 Sponsored by: Dr. Villinski Committee: Dr. Barreto and Dr. Brown Contents I. Why colonize Mars? ............................................................................................................................ 2 II. Can We Colonize Mars? .................................................................................................................... 11 III. What would it look like? ............................................................................................................... 16 A. National Program ......................................................................................................................... -

ROVING ACROSS MARS: SEARCHING for EVIDENCE of FORMER HABITABLE ENVIRONMENTS Michael H

PERSPECTIVE ROVING ACROSS MARS: SEARCHING FOR EVIDENCE OF FORMER HABITABLE ENVIRONMENTS Michael H. Carr* My love affair with Mars started in the late 1960s when I was appointed a member of the Mariner 9 and Viking Orbiter imaging teams. The global surveys of these two missions revealed a geological wonderland in which many of the geological processes that operate here on Earth operate also on Mars, but on a grander scale. I was subsequently involved in almost every Mars mission, both US and non- US, through the early 2000s, and wrote several books on Mars, most recently The Surface of Mars (Carr 2006). I also participated extensively in NASA’s long-range strategic planning for Mars exploration, including assessment of the merits of various techniques, such as penetrators, Mars rovers showing their evolution from 1996 to the present day. FIGURE 1 balloons, airplanes, and rovers. I am, therefore, following the results In the foreground is the tethered rover, Sojourner, launched in 1996. On the left is a model of the rovers Spirit and Opportunity, launched in 2004. from Curiosity with considerable interest. On the right is Curiosity, launched in 2011. IMAGE CREDIT: NASA/JPL-CALTECH The six papers in this issue outline some of the fi ndings of the Mars rover Curiosity, which has spent the last two years on the Martian surface looking for evidence of past habitable conditions. It is not the fi rst rover to explore Mars, but it is by far the most capable (FIG. 1). modest-sized landed vehicles. Advances in guidance enabled landing Included on the vehicle are a number of cameras, an alpha particle at more interesting and promising places, and advances in robotics led X-ray spectrometer (APXS) for contact elemental composition, a spec- to vehicles with more independent capabilities. -

Educator's Guide

EDUCATOR’S GUIDE ABOUT THE FILM Dear Educator, “ROVING MARS”is an exciting adventure that This movie details the development of Spirit and follows the journey of NASA’s Mars Exploration Opportunity from their assembly through their Rovers through the eyes of scientists and engineers fantastic discoveries, discoveries that have set the at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Steve Squyres, pace for a whole new era of Mars exploration: from the lead science investigator from Cornell University. the search for habitats to the search for past or present Their collective dream of Mars exploration came life… and maybe even to human exploration one day. true when two rovers landed on Mars and began Having lasted many times longer than their original their scientific quest to understand whether Mars plan of 90 Martian days (sols), Spirit and Opportunity ever could have been a habitat for life. have confirmed that water persisted on Mars, and Since the 1960s, when humans began sending the that a Martian habitat for life is a possibility. While first tentative interplanetary probes out into the solar they continue their studies, what lies ahead are system, two-thirds of all missions to Mars have NASA missions that not only “follow the water” on failed. The technical challenges are tremendous: Mars, but also “follow the carbon,” a building block building robots that can withstand the tremendous of life. In the next decade, precision landers and shaking of launch; six months in the deep cold of rovers may even search for evidence of life itself, space; a hurtling descent through the atmosphere either signs of past microbial life in the rock record (going from 10,000 miles per hour to 0 in only six or signs of past or present life where reserves of minutes!); bouncing as high as a three-story building water ice lie beneath the Martian surface today. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

Combinatorics in Space

Combinatorics in Space The Mariner 9 Telemetry System Mariner 9 Mission Launched: May 30, 1971 Arrived: Nov. 14, 1971 Turned Off: Oct. 27, 1972 Mission Objectives: (Mariner 8): Map 70% of Martian surface. (Mariner 9): Study temporal changes in Martian atmosphere and surface features. Live TV A black and white TV camera was used to broadcast “live” pictures of the Martian surface. Each photo-receptor in the camera measures the brightness of a section of the Martian surface about 4-5 km square, and outputs a grayness value in the range 0-63. This value is represented as a binary 6-tuple. The TV image is thus digitalized by the photo-receptor bank and is output as a stream of thousands of binary 6-tuples. Coding Needed Without coding and a failure probability p = 0.05, 26% of the image would be in error ... unacceptably poor quality for the nature of the mission. Any coding will increase the length of the transmitted message. Due to power constraints on board the probe and equipment constraints at the receiving stations on Earth, the coded message could not be much more than 5 times as long as the data. Thus, a 6-tuple of data could be coded as a codeword of about 30 bits in length. Other concerns A second concern involves the coding procedure. Storage of data requires shielding of the storage media – this is dead weight aboard the probe and economics require that there be little dead weight. Coding should therefore be done “on the fly”, without permanent memory requirements. -

Mars Exploration - a Story Fifty Years Long Giuseppe Pezzella and Antonio Viviani

Chapter Introductory Chapter: Mars Exploration - A Story Fifty Years Long Giuseppe Pezzella and Antonio Viviani 1. Introduction Mars has been a goal of exploration programs of the most important space agencies all over the world for decades. It is, in fact, the most investigated celestial body of the Solar System. Mars robotic exploration began in the 1960s of the twentieth century by means of several space probes sent by the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR). In the recent past, also European, Japanese, and Indian spacecrafts reached Mars; while other countries, such as China and the United Arab Emirates, aim to send spacecraft toward the red planet in the next future. 1.1 Exploration aims The high number of mission explorations to Mars clearly points out the impor- tance of Mars within the Solar System. Thus, the question is: “Why this great interest in Mars exploration?” The interest in Mars is due to several practical, scientific, and strategic reasons. In the practical sense, Mars is the most accessible planet in the Solar System [1]. It is the second closest planet to Earth, besides Venus, averaging about 360 million kilometers apart between the furthest and closest points in its orbit. Earth and Mars feature great similarities. For instance, both planets rotate on an axis with quite the same rotation velocity and tilt angle. The length of a day on Earth is 24 h, while slightly longer on Mars at 24 h and 37 min. The tilt of Earth axis is 23.5 deg, and Mars tilts slightly more at 25.2 deg [2]. -

Mars Field Geology, Biology, and Paleontology Workshop, Summary

MARS FIELD GEOLOGY, BIOLOGY, AND PALEONTOLOGY WORKSHOP: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS November 18–19, 1998 Space Center Houston, Houston, Texas LPI Contribution No. 968 MARS FIELD GEOLOGY, BIOLOGY, AND PALEONTOLOGY WORKSHOP: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS November 18–19, 1998 Space Center Houston Edited by Nancy Ann Budden Lunar and Planetary Institute Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 LPI Contribution No. 968 Compiled in 1999 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautcis and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This volume may be cited as Budden N. A., ed. (1999) Mars Field Geology, Biology, and Paleontology Workshop: Summary and Recommendations. LPI Contribution No. 968, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 80 pp. This volume is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Phone: 281-486-2172 Fax: 281-486-2186 E-mail: [email protected] Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost of shipping and handling. _________________ Cover: Mars test suit subject and field geologist Dean Eppler overlooking Meteor Crater, Arizona, in Mark III Mars EVA suit. PREFACE In November 1998 the Lunar and Planetary Institute, under the sponsorship of the NASA/HEDS (Human Exploration and Development of Space) Enterprise, held a workshop to explore the objectives, desired capabilities, and operational requirements for the first human exploration of Mars.