The Asian EFL Journal Professional Teaching Articles July 2015 Issue 85

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Association of Academic/Research Librarians, Inc

PHILIPPINE ASSOCIATION OF ACADEMIC/RESEARCH LIBRARIANS, INC. Rm. 301, THE NATIONAL LIBRARY BUILDING, T.M. KALAW ST., ERMITA MANILA 1000, PHILIPPINES www.paarl.org.ph EXECUTIVE BOARD 2017 President CALL FOR PAPERS ANA MARIA B. FRESNIDO De La Salle University 2401 Taft Avenue, Malate, Manila Email: [email protected] Telephone: 524-88-35 22 November 2017 Vice-President CHITO N. ANGELES Dear Colleagues and Friends: University of the Philippines Diliman Diliman, Quezon City Email: [email protected] The Philippine Association of Academic/Research Librarians, Inc. (PAARL) is pleased to Telephone: 981-85-00 loc. 2852 announce its call for papers for the 2018 Summer Conference with the theme User Secretary Experience (UX) Matters! : Looking at Library Services from a User Perspective to be held on REINA FLOR A. CASTRO 25-27 April 2018 in Palawan. The call is open to librarians/information professionals, Baliuag University Baliwag, Bulacan researchers, faculty, and students of Library and Information Science. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 766-20-45 loc. 407 The conference aims to encourage librarians, particularly library managers and Treasurer administrators, to look at how and why clients actually use libraries (as opposed to the ESTELA A. MONTEJO librarians’ perceptions of what the clients need and how they interact with the libraries) in Ateneo de Manila University Loyola Heights, Quezon City order to better understand the users’ needs and to further improve the library’s services, Email: [email protected] facilities, and resources. Telephone: 426-60-01 loc. 5566 Auditor Full papers must be emailed to [email protected] on or before 26 February FERNAN R. -

List of Private Granted with Authority for SY 2013-2014

Department of Education Region III DIVISION OF BULACAN City of Malolos LIST OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS BULACAN WITH AUTHORITY TO OPERATE FOR SCHOOL YEAR 2013-2014 (as of April 30, 2013 Authority Granted to Operate No. Name of School/Address Municipality Pre-Elementary Elementary Secondary Gov't. Recognition 1 Angat Ecumenical K/S, Sta. Cruz Angat No. E-027, s. 2006 Colegio de Sta. Monica de Angat, Gov't. Recognition No. Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition 2 Angat Poblacion E- 018, s. 1986 No E- 018, s. 1986 No S-002, s. 1991 F.D. Roosevelt Memorial School, Gov't. Recognition 3 Angat Poblacion No S-031, s. 2005 Kalinangan Integrated School, Sto. Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition 4 Angat Cristo No E- 060, s. 1994 No E-045, s. 1997 No.S-001, s. 2001 Lourdes College of Bulacan, Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition 5 Angat Sulucan No 150, s. 1975 No E-020, s. 2008 No AR- 42, s. 1980 Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Permit No. E- 6 Wisdom Jade Academy, Niugan Angat No 059, s. 2012 298, s. 2012 Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition 7 A-Z Country Day School, Borol 2nd Balagtas No. E-052, s. 2001 No. E-086, s.2001 No. S-026, s. 2002 ABACADA School of the Future Inc. , Gov't Permit Gov't Permit 8 Balagtas Wawa, SY 13-14 No. E-170, s. 2013 No. E-170, s. 2013 Gov't. Recognition Gov't. Recognition 9 Balagtas Montessori School Inc., Panginay Balagtas No. -

SEED Conference

NewsletterOfficial Publication of the Office of the Vice President for Linkages and International Affairs, San Beda University, Manila, Philippines April 2018 Volume 1 Issue 2 SEED Conference Premieres in the Philippines In this issue: Larry Javier Ambion ministrators (46), faculty (12), staff (6), and SPOTLIGHT students (58) in the said event was the school’s way of showing hospitality and at the same time expertise as some were paper SBU Hosts 1st ALN Execu- presenters and performers in the said event. tive Committee Meeting in the Philippines The conference highlighted paper presenta- tions by delegates including ALN-SEED Pro- Dr. Tita E. Branzuela is gram implementation experiences in Indone- SALT’s New Secretary sia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines. These served as an avenue for knowledge General sharing and generation of opportunities. The attendance in the conference likewise pro- LIA Humbly Flaunts vided insights into the network’s major pro- Research Prowess Prof. Em. Dato’ Ir. Dr. Zainai Bin Mohamed gram thrusts. ALN Chair delivers the keynote address Presentations on Social Enterprise and Inno- The Office of Linkages and International vation, Micro Small and Medium Enterprise, Affairs’ mission to contribute in the and Entrepreneurial Marketing took place Newsletter knowledge generation, skills development, during the conference with the distinguished transformational values acquisition was presenters from different partner universi- EDITORIAL BOARD once again achieved in the recently conclud- ties of Parahyangan Catholic University ed first ASEAN Learning Network – San Be- (Indonesia), Banking University, Ho Chi Minh da University Social Enterprise for Econom- (Vietnam), Universiti Malaysia Kelantan ic Development (SEED) International Con- (Malaysia), Prince of Songkla University Tita Evasco-Branzuela, Ph.D. -

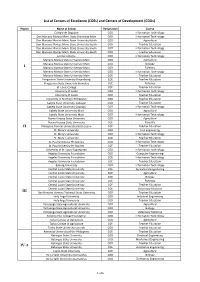

Coes) and Centers of Development (Cods) As of May 2016

Table 8. List of Centers of Excellence (COEs) and Centers of Development (CODs) as of May 2016 Region Name of Higher Education Institution (HEI) Institutional Type Designation Program NCR - National Capital Region Adamson University Private HEIs COD Chemical Engineering Civil Engineering Computer Engineering Electrical Engineering Electronics Engineering Industrial Engineering Teacher Education AMA University Private HEIs COD Information Technology Asia Pacific College Private HEIs COD Computer Engineering COE Information Technology Ateneo de Manila University Private HEIs COD Communication Electronics Engineering Environmental Science History Literature(Kagawaran ng Filipino) Political Science COE Biology Business Administration Chemistry Entrepreneurship Information Technology Literature (Dept of English) Mathematics Philosophy Physics Psychology Sociology Centro Escolar University Private HEIs COD Business Administration Optometry COE Teacher Education De La Salle College of Saint Benilde Private HEIs COE Business Administration Hotel and Restaurant Management De La Salle University Private HEIs COD Computer Engineering History Literature Political Science Statistics COE Accountancy Biology Business Administration Chemical Engineering Chemistry Civil Engineering Electronics Engineering Entrepreneurship Page 1 of 9 Region Name of Higher Education Institution (HEI) Institutional Type Designation Program Industrial Engineering Information Technology Mathematics Mechanical Engineering Physics Teacher Education Far Eastern University Private -

Deiled Department of Education Region Lll DMISION of BULACAN Malolos City

Republic of the Philippines DeilED Department of Education Region lll DMISION OF BULACAN Malolos City Mav 3,V012 DIVISION MEMORANDUM No. rM. s.2012 TRAINING OF TEACHERSON THE IIIPLEMENTANOil OF THE GRADE 7 CURRICULUM OF THE K TO 12 BASIC EDUGATION PROGRAM FOR SY2012.2013 To: Education Program SuPervisors Secondary School Heads/OlCs 1. The K to 12 Basic Education Program starts this school year 2012-2013 wifir the implementation of Grades 1 and 7. ln this regard, tre training of Grade 7 teachers for all subject areas will be conducted in two (2) Teacher Education lnstitulions namely Baliuag Univensity and Bulacan State University as per schedule shown below: DATE SUBJEGTAREA VET{UE May 7-11,2012 Science Baliuag UniversitY Baliuag, Bulacan Values Education (EsP) Bulaean State University Mapeh Malolos Cifi, Bulacan May 14-18,2012 Mathematics Baliuag University Baliuag, Bulacan Filipino Bulacan State University Araling Panlipunan Malolos City, Bulacan May ?1-25,2012 English Baliuag University Baliuag, Bulacan TLE Bulacan State Universi$ Malolos City, Bulacan 2. The faining aims to a) orient the participants on the salient features and core elements of the Kto 12 Curriculum; b) develop the partcipants' capacity to effectively and effciently implement the Gride 7 curriculum in their area of specialization. 3. Enclosure No. 1 provides the number of participants for each school as per list of grade 7 teachers submitted to this Ofiice. Head Teachers/Departnent Heads are requested to atend the said faining on a sit-in basis. 4. Participants are expected to register at the faining venues on Day 1 at 7:00 Alttl. -

Barriers to E-Learning in Developing Countries: a Comparative Study

Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 15th May 2019. Vol.97. No 9 © 2005 – ongoing JATIT & LLS ISSN: 1992-8645 www.jatit.org E-ISSN: 1817-3195 BARRIERS TO E-LEARNING IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY SOLOMON OLUYINKA, ANATALIA N. ENDOZO Faculty, College of Business Administration and Accountancy, Baliuag University, Gil Carlos St, Baliuag, 3006 Bulacan, Philippines Faculty, College of Education, Angeles University Foundation, 2009 Angeles City, Philippines Email: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Technology and its applications have given tertiary-organizations a better operating system to broaden their education, learning anywhere and at any time made flexible with adoption of technology that is globally accepted. Several studies investigated factors hindering, influencing or significant to technology acceptance. Unfortunately, comparing technology acceptance in terms of two or more developing countries seems not fully investigated, especially in the area of learning via web in the developing countries, rather than developed countries. This study employed technology acceptance model (TAM) to compare the factors affecting e-learning among the Nigeria and Philippines students, modules/part-time students in universities approved for specified technology considered as the unit of analysis. AMOS-SPSS utilized to the analyse sum of 1306 responses for the two counties. Hypothesized; electric supply, technical resources, ease to use and perceived usefulness on e-learning supported, 69% and 80% variance explained of the study achieved. Although, electric supply regressed on perceived ease not supported. Thus, recommended the replication of this study to increase the generalizability of achieved results. KEYWORDS: Technology Acceptance Model, AMOS-SPSS, Online Learning, Nigeria, Philippines 1. -

(Coes) and Centers of Development (Cods) IV-A

List of Centers of Excellence (COEs) and Centers of Development (CODs) Region Name of School Designation Course Colegio de Dagupan COD Information Technology Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-Main COD Information Technology Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-North COD Agriculture Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-North COD Teacher Education Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-South COD Information Technology Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-South COD Teacher Education Lorma Colleges COD Information Technology Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Agriculture I Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Biology Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Forestry Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Information Technology Mariano Marcos State University-Main COE Teacher Education Pangasinan State University-Bayambang COE Teacher Education Pangasinan State University-Binmaley COE Fisheries St. Louis College COE Teacher Education University of Luzon COD Information Technology University of Luzon COD Teacher Education University of Northern Philippines COD Teacher Education Isabela State University-Cabagan COD Teacher Education Isabela State University-Cauayan COD Information Technology Isabela State University-Main COD Agriculture Isabela State University-Main COD Information Technology Nueva Vizcaya State University COD Agriculture Nueva Vizcaya State University COE Forestry II Philippine Normal University-North Luzon COE Teacher Education St. Mary's University COD Civil Engineering St. Mary's University -

BEEHIVE Academic Stakeholder Database in Indonesia and the Philippines

BEEHIVE Academic Stakeholder Database in Indonesia and the Philippines No Country University Contact person's position* Partner 1 ID Universitas Surabaya (UBAYA) Vice Rector P6 2 ID Universitas Islam Sultan Agung (UNISSULA) 1. Vice Rector I P6 2. Kepala Direktorat Penjaminan Mutu 3 ID Universitas Bunda Mulina (UBM) Coordinator P6 4 ID Universitas Pakuan Entrepreneurship Coordinator P6 5 ID Universitas Sanata Dharma Kepala Biro Kerja Sama dan Hubungan Internasional P6 6 ID Universitas Katolik Atmajaya 1. Vice Rector Collaboration, Research & Strategic Planning P6 2. Faculty of Administration Business Program 7 ID Universitas Gadjah Mada Dean, Former Chairman of SMEDC – Small and Medium P6 Entreprise Development Center UGM 8 ID Universitas Nasional Secretary, Entrepreneurship Program P6 9 ID Universitas Multimedia Nusantara (UMN) Incubator Relation Officer P6 10 ID Universitas Trunojoyo Madura Head of Business Incubator P6 11 ID Universitas Islam Negeri Mataram Head of Business Center P6 12 ID Universitas Mataram Accounting and Reporting Staff P7 13 ID Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta Vice Rector II P7 14 ID UIN Walisongo Vice Dean of Faculty of Health and Psychology P7 15 ID Universitas Tadulako Vice Rector of Financial and General Affairs P7 16 ID Universitas Negeri Jakarta Vice Rector II of Financial and General Affairs P7 17 ID Universitas Negeri Semarang Vice Rector of Financial and General Affairs P7 18 ID Universitas Sebelas Maret 1.Vice Rector of Financial and General Affairs P7 2. Head of Business Administration Agency 19 ID Universitas -

Higher Education in ASEAN

Higher Education in ASEAN © Copyright, The International Association of Universities (IAU), October, 2016 The contents of the publication may be reproduced in part or in full for non-commercial purposes, provided that reference to IAU and the date of the document is clearly and visibly cited. Publication prepared by Stefanie Mallow, IAU Printed by Suranaree University of Technology On the occasion of Hosted by a consortium of four Thai universities: 2 Foreword The Ninth ASEAN Education Ministers Qualifications Reference Framework (AQRF) Meeting (May 2016, in Malaysia), in Governance and Structure, and the plans to conjunction with the Third ASEAN Plus institutionalize the AQRF processes on a Three Education Ministers Meeting, and voluntary basis at the national and regional the Third East Asia Summit of Education levels. All these will help enhance quality, Ministers hold a number of promises. With credit transfer and student mobility, as well as the theme “Fostering ASEAN Community of university collaboration and people-to-people Learners: Empowering Lives through connectivity which are all crucial in realigning Education,” these meetings distinctly the diverse education systems and emphasized children and young people as the opportunities, as well as creating a more collective stakeholders and focus of coordinated, cohesive and coherent ASEAN. cooperation in education in ASEAN and among the Member States. The Ministers also The IAU is particularly pleased to note that the affirmed the important role of education in Meeting approved the revised Charter of the promoting a better quality of life for children ASEAN University Network (AUN), better and young people, and in providing them with aligned with the new developments in ASEAN. -

TESOL International Journal Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages

TESOL International Journal Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Volume 15 Issue 2 2020 ISSN 2094-3938 Published by the TESOL International Journal http://www.tesol-international- journal.com © English Language Education Publishing Brisbane Australia This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of English Language Education Publishing. No unauthorized photocopying All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of English Language Education Publishing. Chief Editors: Dr. Custódio Martins Ramón Medriano, Jr. ISSN. 2094-3938 2020 Volume 15 Issue 2 2020 ISSN 2094-3938 TESOL International Journal Chief Editors Custódio Martins University of Saint Joseph, Macao Ramón Medriano, Jr. Pangasinan State University – School of Advanced Studies Senior Associate Editors Jun Zhao Peter Ilič Farzaneh Khodabandeh Augsuta University, The University of Aizu, Payame Noor University, USA Japan Iran Associate Editors Mário Pinharanda Nunes Sharif Alghazo Khadijeh Jafari University of Macao, China University of Jordan, Gorgan Islamic Azad Jordan University, Iran Rining Wei Harriet Lowe Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, China University of Greenwich, UK 2020 Volume 15 Issue 2 2020 ISSN 2094-3938 Editorial Board Abdel Hamid Mohamed - Lecturer, Qatar University, Kambara, Hitomi - The University -

No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address No

ANNEX B * STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address Polytechnic University of the 1 Bataan Peninsula State University All Campuses 20 Eastern Visayas State University All Campuses 39 All Campuses Philippines Ramon Magsaysay Technological 2 Batangas State University All Campuses 21 Ifugao State University All Campuses 40 All Campuses University 3 Benguet State University All Campuses 22 Isabela State University All Campuses 41 Rizal Technological University All Campuses 4 Bicol University All Campuses 23 Kalinga-Apayao State College All Campuses 42 Samar State University All Campuses 5 Bukidnon State University All Campuses 24 Leyte Normal University All Campuses 43 Sultan Kudarat State University All Campuses 6 Bulacan State University All Campuses 25 Mariano Marcos State University All Campuses 44 Tarlac College of Agriculture All Campuses Mindanao University of Science and 7 Cagayan State University All Campuses 26 All Campuses 45 Tarlac State University All Campuses Technology Mt. Province State Polytechnic Technological University of the 8 Camarines Sur Polytechnic College All Campuses 27 All Campuses 46 All Campuses College Philippines 9 Capiz State University All Campuses 28 Naval State University All Campuses 47 University of Antique All Campuses 10 Catanduanes State College All Campuses 29 Negros Oriental State University All Campuses 48 University of Eastern Philippines All Campuses 11 Cavite State University All Campuses 30 Northwest Samar State University -

International Education Guide

International Education Guide FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF EDUCATION FROM THE PHILIPPINES Welcome to the Alberta Government’s International Education Guides The International Qualifications Assessment Service (IQAS) developed the International Education Guides for educational institutions, employers and professional licensing bodies to help facilitate and streamline their decisions regarding the recognition of international credentials. These guides compare educational systems from around the world to educational standards in Canada. The assessment recommendations contained in the guides are based on extensive research and well documented standards and criteria. This research project, a first in Canada, is based on a broad range of international resources and considerable expertise within the IQAS program. Organizations can use these guides to make accurate and efficient decisions regarding the recognition of international credentials. The International Education Guides serve as a resource comparing Alberta standards with those of other countries, and will assist all those who need to make informed decisions, including: • employers who need to know whether an applicant with international credentials meets the educational requirements for a job, and how to obtain information comparing the applicant’s credentials to educational standards in Alberta and Canada • educational institutions that need to make a decision about whether a prospective student meets the education requirements for admission, and who need to find accurate and reliable information about the educational system of another country • professional licensing bodies that need to know whether an applicant meets the educational standards for licensing bodies The guides include a country overview, historical educational overview, description of school education, higher education, professional/technical/vocational education, teacher education, grading scales, documentation for educational credentials and a bibliography.