Application for Declaration of the Airside Services at Sydney Airport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

1.4. Coding and Decoding of Airlines 1.4.1. Coding Of

1.4. CODING AND DECODING OF AIRLINES 1.4.1. CODING OF AIRLINES In addition to the airlines' full names in alphabetical order the list below also contains: - Column 1: the airlines' prefix numbers (Cargo) - Column 2: the airlines' 2 character designators - Column 3: the airlines' 3 letter designators A Explanation of symbols: + IATA Member & IATA Associate Member * controlled duplication # Party to the IATA Standard Interline Traffic Agreement (see section 8.1.1.) © Cargo carrier only Full name of carrier 1 2 3 40-Mile Air, Ltd. Q5 MLA AAA - Air Alps Aviation A6 LPV AB Varmlandsflyg T9 ABX Air, Inc. © 832 GB Ada Air + 121 ZY ADE Adria Airways + # 165 JP ADR Aegean Airlines S.A. + # 390 A3 AEE Aer Arann Express (Comharbairt Gaillimh Teo) 809 RE REA Aeris SH AIS Aer Lingus Limited + # 053 EI EIN Aero Airlines A.S. 350 EE Aero Asia International Ltd. + # 532 E4 Aero Benin S.A. EM Aero California + 078 JR SER Aero-Charter 187 DW UCR Aero Continente 929 N6 ACQ Aero Continente Dominicana 9D Aero Express Del Ecuador - Trans AM © 144 7T Aero Honduras S.A. d/b/a/ Sol Air 4S Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Aero Lloyd Flugreisen GmbH & Co. YP AEF Aero Republica S.A. 845 P5 RPB Aero Zambia + # 509 Z9 Aero-Condor S.A. Q6 Aero Contractors Company of Nigeria Ltd. AJ NIG Aero-Service BF Aerocaribe 723 QA CBE Aerocaribbean S.A. 164 7L CRN Aerocontinente Chile S.A. C7 Aeroejecutivo S.A. de C.V. 456 SX AJO Aeroflot Russian Airlines + # 555 SU AFL Aeroflot-Don 733 D9 DNV Aerofreight Airlines JSC RS Aeroline GmbH 7E AWU Aerolineas Argentinas + # 044 AR ARG Aerolineas Centrales de Colombia (ACES) + 137 VX AES Aerolineas de Baleares AeBal 059 DF ABH Aerolineas Dominicanas S.A. -

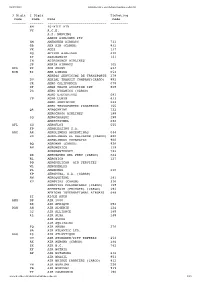

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A. -

Inquiry Into the Operation, Regulation and Funding of Air Route Service Delivery to Rural, Regional and Remote Communities

Professor Rico Merkert Professor and Chair in Transport and Supply Chain Management Deputy Director, Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies The University of Sydney Business School Sydney, 05 February 2018 Dr Jane Thomson Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee Inquiry into the operation, regulation and funding of air route service delivery to rural, regional and remote communities Dear Dr Thomson, Thank you for inviting me to make a submission to the above Inquiry. The aim of this submission is to address the operation, regulation and funding of air route service delivery to rural, regional and remote communities, with particular reference to a number of key areas that were pointed out in your letter which will form the structure of this submission. Paramount to finding equitable and efficient solutions to issues raised by the Inquiry is to recognise regional air services as being essential for the future development of Australia. The federal government has many options to improve requisite commercial viability of scheduled regional air services (i.e. through better integration at various levels and more relaxed security regulation) which should in return improve connectivity, accessibility of transport/mobility and frequency of flights and overall social, health, cultural and economic activity. 1. social and economic impacts of air route supply and airfare pricing; Aviation has a significantly positive impact on economies, businesses and communities. This has been evidenced by a large amount of empirical studies (e.g. Oxford Economics and ATAG, 2014)1. It is widely accepted that aviation plays an even more vital role in the regional, rural and remote (RRR) context. -

NSW Intrastate Regional Aviation Statistics V

NSW Intrastate Regional Aviation Statistics October 2016 | Version: 1.0 Contents 1 About the Data...........................................................................................................3 2 Notes about the data .................................................................................................4 2.1 Route related events.....................................................................................4 2.2 Non-route related events ..............................................................................5 3 Dataset description....................................................................................................7 Author: Transport Services Policy Date: October 2016 Version: 1.0 Reference: Technical Documentation Division: Freight Strategy and Planning NSW Intrastate Regional Aviation Services – October 2016 2 1 About the Data The data featured here are patronage statistics for all intrastate air services that fly to and from Sydney. This data is collected quarterly under the Air Transport Regulation 2016. The patronage data dates back to 1996/97. NSW Intrastate Regional Aviation Services – October 2016 3 2 Notes about the data This section summarises the events in the industry that may be relevant in the understanding and interpretation of this dataset: 2.1 Route related events May 2000 Horizon Airlines withdraws from the Deniliquin-Sydney route. January 2001 Yanda Airlines withdraws from Coonabarabran-Sydney, Gunnedah-Sydney, Maitland-Sydney, Scone-Sydney and Singleton-Sydney. May 2001 -

Order 7340.1Z, Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.1Z CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to change 3 of Order 7340.1Z, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; all air traffic field offices and field facilities; all airway facilities field offices; all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. February 14, 2008. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the Page Control Chart attachment. Nancy B. Kalinowski Acting Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: __________________ Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 02/14/08 7340.1Z CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM-1-1 and CAM-1-10 10/25/07 CAM-1-1 and CAM-1-2 02/14/08 1-1-1 10/25/07 1-1-1 02/14/08 3-1-15 through 3-1-18 03/15/07 3-1-15 through 3-1-18 02/14/08 3-1-35 03/15/07 3-1-35 03/15/07 3-1-36 03/15/07 3-1-36 02/14/08 3-1-45 03/15/07 3-1-45 02/14/08 3-1-46 10/25/07 3-1-46 10/25/07 3-1-47 -

Change Federal Aviation Administration Jo 7340.2 Chg 1

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION JO 7340.2 CHG 1 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. September 25, 2008. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the Page Control Chart attachment. Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 9/25/08 JO 7340.2 CHG 1 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 and CAM−1−2 . 06/05/08 CAM−1−1 and CAM−1−2 . 06/05/08 3−1−1 . 06/05/08 3−1−1 . 06/05/08 3−1−2 . 06/05/08 3−1−2 . 09/25/08 3−1−17 . 06/05/08 3−1−17 . 06/05/08 3−1−18 . 06/05/08 3−1−18 . 09/25/08 3−1−23 through 3−1−26 . -

Interim Report Air Services

NO. 446A PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL STANDING COMMITTEE ON STATE DEVELOPMENT Interim Report on Provision and operation of rural and regional air services in New South Wales Ordered to be printed Thursday 24 September 1998 REPORT NO. 20, VOLUME ONE SEPTEMBER 1998 ISBN 0-7313-9712-6 INQUIRY’S TERMS OF REFERENCE Provision and operation of rural and regional air services in New South Wales (Reference received 28 May 1998) That the Standing Committee on State Development inquire into and report on the provision and operation of rural and regional air services in New South Wales, and in particular the impact on country communities of: C landing fees at Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport; C landing fees at regional airports; C the allocation of slot times at Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport; C proposals to limit access to Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport and direct country services to Bankstown Airport; and C the impacts of deregulation of New South Wales air services on the provision of services to smaller regional centres and towns in New South Wales including consideration of measures to maintain services. CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD On 28 May 1998 the Minister for Transport, the Hon Carl Scully, MP, requested that the Standing Committee inquire into and report on the provision and operation of rural and regional air services in New South Wales. The Minister referred this matter to the Standing Committee to ensure that there would be no adverse impacts on rural and regional communities in New South Wales through proposals to deregulate intrastate air services or as a result of changes to pricing and access arrangements at Sydney Airport. -

Altéa Departure Control – Flight

Amadeus Airport IT Airport & Ground Handler Solutions optimise IT Contents Use IT to optimise your airport operations 1 Use IT to optimise your airport operations Why Amadeus? 2 The growth of worldwide airline traffic creates increasing challenges for airports and ground > Fast-growing development in Airport IT Services 4 handlers. They need to handle more and more passengers while also operating in the same space, managing increasing security constraints and improving customer satisfaction. They need to > Innovative & proven solutions 6 seamlessly connect more and more passengers with more and more flights. > New generation technology 8 Winning airports that want to attract a larger share of traffic and ground handlers that want to be selected to manage the flights and customers of demanding airlines need to assess and modernise > Migration & transformation expertise 10 their operations to offer the most customer-centric, efficient and cost-competitive airport processes. > Best-in-class IT services 12 Amadeus believes that innovative IT solutions are critical to achieving a transformation that will not only deliver cost and productivity savings in the short run, but also enable customers to adapt their > Superior value for money 14 business models in the long run. What do we offer? 16 The power of new generation IT solutions The right technology partner > Amadeus Airport IT Portfolio overview 17 IT solutions like your departure control system (DCS) and self Very few airlines and airports, and even fewer ground handlers, service system are critical to operating your business in an have the dedicated time and resources necessary to build and optimised way. implement new generation customer and flight management > Altéa Departure Control 18 They define the entire customer and flight management process solutions and achieve such a transformation on their own. -

Graduate Student Policy

National Evolutionary Synthesis Center 2024 W. Main St., Suite A200 Durham, NC 27705 USA http://www.nescent.org 919-668-4551 NESCent Graduate Student Fellowship Policy Graduate Student Fellows are supported to enable synthetic research on any aspect of evolutionary science and relevant disciplines. Fellows will work on-site at NESCent for periods of one semester (4.5 months). Fellows may also receive pre-approval to work on their proposed research at other institutions during their fellowship. This determination will be made on a case by case basis. NESCent will provide support for airfare to and from NESCent and a housing allowance up to $91/day for non-local fellows. The following information is an overview of your travel plans for your trip to NESCent. For further assistance please contact Danielle Wilson at NESCent via email [email protected] or 919- 668-4545. 1. Travel Arrangements: We can reimburse you for one round-trip, 21-day advance, economy class ticket to NESCent up to the following (in USD): Eastern - $500 Eastern Europe - $2,000 Midwest - $600 Africa - $2,250 Western - $750 Russia - $2,500 Western Europe - $1,500 Australia/New Zealand - $2,800 South America - $1,300 Travel arrangements should be made through our travel agent. Your economy class airfare will be directly billed to NESCent. Please note that as a condition of your invitation, we ask that your travel plans be ticketed no less than 21 days in advance of your arrival at NESCent. Please contact our travel agent as soon as possible to arrange your airline travel. Contact information will be provided under a separate cover.