Should Europe Help Syrian Refugees Return Home?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 Syrian Presidential Election

July 2021 The 2021 Syrian Presidential Election Political deadlock and Syrian Burnout Hadia Kawikji Introduction The legitimacy of any position is based on two main elements, first the manner in which the individual attained the position, and second is the ability of the individual to fulfill the related responsibilities. For the first point, Bashar al-Assad’s Presidency in Syria was attained through heredity within a ludicrous system following his father who seized the power via a military coup. Both father and son ruled Syria for the last half a century with de-facto legitimacy, through nominal referendums completely dominated by the Ba’ath party. This was instead of an election that reflects the Syrian people’s will. In terms of the ability to fulfill the responsibilities of the presidency, many indicators showcase the regime’s failures to the Syrians. The recent years have witnessed the collapse of the Syrian pound to unprecedented levels, along with the displacement of more than half of the Syrian population,1 and the rise of extreme poverty to 82%,2 with the fact that 37% of the Syrian territories are outside of the regime’s control. Additionally, the violation of the Syrian decision is evidenced by the control of the Lebanese “Hezbollah”, Iranian militias, and Russian troops controlling over roughly 85% of the Syrian borders, finally yet importantly, the Syrian regime’s inability to protect its territory is illustrated by the haphazard attacks by Israel on Syrian land at any given time. In March 2011, the majority of the Syrian people called for the removal of the Assad regime and the transition to a democratic country. -

Transformations in United States Policy Toward Syria Under Bashar

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses CAHSS Theses and Dissertations and Dissertations 1-1-2017 Transformations in United States Policy toward Syria Under Bashar Al Assad A Unique Case Study of Three Presidential Administrations and a Projection of Future Policy Directions Mohammad Alkahtani Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Mohammad Alkahtani. 2017. Transformations in United States Policy toward Syria Under Bashar Al Assad A Unique Case Study of Three Presidential Administrations and a Projection of Future Policy Directions. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences – Department of Conflict Resolution Studies. (103) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd/103. This Dissertation is brought to you by the CAHSS Theses and Dissertations at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Economic Sanctions Case 2011-2: EU, US V. Syrian Arab Republic (2011

Case Studies in Economic Sanctions and Terrorism Case 2011-2 EU, US v. Syrian Arab Republic (2011– : human rights, democracy) Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Peterson Institute for International Economics Jeffrey J. Schott, Peterson Institute for International Economics Kimberly Ann Elliott, Peterson Institute for International Economics Julia Muir, Peterson Institute for International Economics July 2011 © Peterson Institute for International Economics. All rights reserved. See also: Cases 86-1 US v. Syria (1986– : Terrorism) Additional country case studies can be found in Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, May 2008 Summary Post‐2000 the United States has imposed three rounds of sanctions against Syria, in response to: (1) Syria’s support for terrorist groups and terrorist activities in Iraq; (2) its pursuit of missiles and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs; and (3) the occupation of Lebanon. In May 2004, President George W. Bush issued Executive Order 13338, implementing the provisions in the Syria Accountability Act, including a freeze of assets of specified individuals and a ban on munitions and dual use items, a ban on exports to Syria other than food and medicine, and a ban on Syrian aircraft landing in or overflying the United States. Sanctions also required US financial institutions to sever correspondent accounts with the Commercial Bank of Syria because of money laundering concerns. In April 2006, Executive Order 13399 was implemented, which designates the Commercial Bank of Syria, including its subsidiary, Syrian Lebanese Commercial Bank, as a financial institution of primary money laundering concern and orders US banks to sever all ties with the institution. In February 2008 the United States issued Executive Order 13460, which freezes the assets of additional individuals. -

The Russian-Syrian Connection

The Russian-Syrian Connection: Thwarting Democracy in the Middle East and the Greater OSCE Region Wednesday, March 9, 2005 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM 226 Dirksen Senate Office Building Statement for the record of Prof. Walid Phares, Florida Atlantic University and senior fellow, Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Mr Chairman, Mr Ranking member, members of the United States Helsinki Commission. I am pleased to participate in this timely hearing on the subject of Russian involvement with Syria. I shall focus my remarks upon the impact of Russian-Syrian relations on Lebanon. I am a professor of international relations, an expert on terrorism and am originally from Lebanon. I am the Secretary-General of the World Lebanese Cultural Union, and in that capacity I have just been in New York where I met seven ambassadors to the UN Security Council (Algeria, Argentina, Brazil, France, Greece, Russia, US) and the Deputy Secretary General for Middle Eastern affairs. While I am not an international lawyer, I shall draw your attention to international legal standards which I sincerely believe Russia is not meeting. As you know, the present turmoil in Lebanon stems from the assassination of the former prime minister, Rafiq Hariri, on February 14, 2005. Mr Hariri’s murder was, however, not a bolt from the blue. Rather, his brutal removal from the political scene followed months of threats by Syria and its proxies against Lebanese who have sought the end of the Syrian occupation of Lebanon in compliance with UN Security Council Resolution 1559 of September 2, 2004 (UNSCR 1559/2004). -

London School of Economics and Political Science

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online London School of Economics and Political Science Understanding and Explaining US-Syrian Relations: Conflict and Cooperation, and the Role of Ideology Jasmine K. Gani A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2011. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the author's prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 114,900 words. (Approved word limit: 115,000). 2 Abstract This thesis is a study of US-Syrian relations, and the legacy of mistrust between the two states. While there has been a recent growth in the study of Syria’s domestic and regional politics, its foreign policy in a global systemic context remains understudied within mainstream International Relations (IR), Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA), and even Middle Eastern studies, despite Syria’s geo-political centrality in the region. -

Statement of Unrwa Commissioner-General to the Virtual Advisory Commission – 23 November 2020

STATEMENT OF UNRWA COMMISSIONER-GENERAL TO THE VIRTUAL ADVISORY COMMISSION – 23 NOVEMBER 2020 Mr. Chair, Mr. Vice-Chair, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, I am pleased to be with you here today, at this Advisory Commission meeting. Let me start by thanking the Chair, Mr. Sultan Mohammed Al Shamsi - Assistant Minister for International Development Affairs of the United Arab Emirates. I would like to acknowledge with appreciation the important role as Vice-Chair of Dr. Hassan Mneymneh - President of the Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee. And from the Subcommittee: I thank Ms. Jessica Olausson, Consul General of Sweden, Vice-Chairs: Mr. Jason Tulk, Head of Cooperation, Representative Office of Canada, Palestine, and Engineer Rafiq Khirfan, Director-General of the Department of Palestinian Affairs, Jordan. We are also honored by the presence of India and China as guests: Ambassador Sunil Kumar, the Representative of India to the State of Palestine, and Ms. Wang Xi, Counsellor at the Representative Office of China to the State of Palestine, are attending this Advisory Commission meeting. Finally, I wish to express my deep condolences on the passing of Mr. Saeb Erekat, a greatly respected Palestinian leader and tireless advocate for a just peace. I also wish to offer my deep condolences on the passing of Mr. Walid Muallem, the long-serving Foreign Minister of the Syrian Arab Republic, and a supporter of UNRWA Excellencies, distinguished delegates, On 10th November, I informed the Advisory Commission during an Extraordinary meeting that UNRWA’s core budget had run out of cash. I emphasized that the Agency faced this year a shortfall of 115 million Dollars, of which 70 million Dollars in new contributions are needed to cover November and December salaries of over 28,000 staff. -

Iraq Study Group Consultations

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRESIDENCY IRAQ STUDY GROUP Iraq Study Group Consultations (* denotes meeting took place in Iraq) Iraqi Officials and Representatives * Jalal Talabani - President * Tareq al-Hashemi - Vice President * Adil Abd al-Mahdi - Vice President * Nouri Kamal al-Maliki - Prime Minister * Salaam al-Zawbai - Deputy Prime Minister * Barham Salih - Deputy Prime Minister * Mahmoud al-Mashhadani - Speaker of the Parliament * Mowaffak al-Rubaie - National Security Advisor * Jawad Kadem al-Bolani - Minister of Interior * Abdul Qader Al-Obeidi - Minister of Defense * Hoshyar Zebari - Minister of Foreign Affairs * Bayan Jabr - Minister of Finance * Hussein al-Shahristani - Minster of Oil * Karim Waheed - Minister of Electricity * Akram al-Hakim - Minister of State for National Reconciliation Affairs * Mithal al-Alusi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ayad Jamal al-Din - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ali Khalifa al-Duleimi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Sami al-Ma'ajoon - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Muhammad Ahmed Mahmoud - Member, Commission on National Reconciliation * Wijdan Mikhael - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation Lt. General Nasir Abadi - Deputy Chief of Staff of the Iraqi Joint Forces * Adnan al-Dulaimi - Head of the Tawafuq list Ali Allawi - Former Minister of Finance * Sheik Najeh al-Fetlawi - representative of Muqtada al-Sadr * Abd al-Aziz al-Hakim - Shia Coalition Leader * Sheik Maher al-Hamraa - Ayat Allah -

Syria's Historic Decision to Establish Diplomatic Relations with Lebanon

Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center at the Israel Intelligence Heritage & Commemoration Center (IICC) November 5, 2008 Syria’s historic decision to establish diplomatic relations with Lebanon and an analysis of its implications President Bashar Assad announcing Decree No. 358, which establishes diplomatic relations between Syria and Lebanon (Syrian TV, October 14). OOOvvveeerrrvvviiieeewww 1. On October 14, 2008, Syrian president Bashar Assad issued Decree No 358, ordering the establishment of diplomatic relations between Syria and Lebanon, and the opening of a Syrian embassy in Lebanon (Syrian News Agency, October 14, 2008). The announcement of the decree was preceded by the joint agreement of the presidents of Syria and Lebanon, Bashar Assad and Michel Suleiman, during Suleiman’s visit to Damascus on August 13, 2008. After the visit, Lebanon issued Decree No. 268, for setting up a Lebanese embassy in Syria (September 13, 2008). 2. The day after the Syrian decree, Lebanese foreign minister Fawzi Salukh arrived in Syria for a visit. He met with Bashar Assad and the Syrian foreign minister, Walid Muallem. On the morning of October 15 the two ministers signed a joint announcement to the effect that diplomatic relations would be established. They said that Syria and Lebanon desired to strengthen the “excellent brotherly relations between two sister countries [sic],” based on mutual respect for the sovereignty and independence of each. In answer to a reporter’s question, the Syrian foreign minister said that an ambassador to Syria would be appointed before the end of 2008 (Syrian and Lebanon news agencies, October 15, 2008). 3. Lebanese foreign minister Fawzi Salukh: “We are pleased to announce…the The foreign ministers of Syria and Lebanon sign the establishment of diplomatic relations documents establishing of diplomatic relations (Syrian News between two sister countries.” (Syrian Agency). -

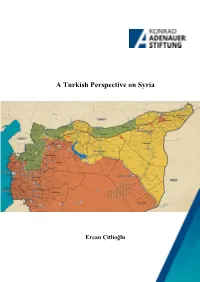

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Sanctioning Assad's Syria

DIIS REPORT 2012:13 DIIS REPORT SANCTIONING ASSAD’S SYRIA MAPPING THE ECONOMIC, SOCIOECONOMIC AND POLITICAL REPERCUSSIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SANCTIONS IMPOSED ON SYRIA SINCE MARCH 2011 Rune Friberg Lyme DIIS REPORT 2012:13 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:13 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protests in Damascus against EU sanctions. © bassim/Xinhua Press/Corbis Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-519-6 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-520-2 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk This report was commissioned by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but its findings and conclusions are entirely the responsibility of the author. Rune Friberg Lyme, Research Assistant [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:13 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 11 1.1 About this report 12 1.2 Structure of the report 12 2. The Syrian economy and power structure reconfiguration in the 2000s 14 2.1 Selective liberalisation process during the 2000s 14 2.2 The basic structure of the Syrian economy 16 2.3 Increasing social and regional inequalities 18 2.4 Reconfiguring the authoritarian powerbase 20 2.5 A decade of shifting power alliances and increasing socioeconomic inequality 23 3. -

US Move Towards Brotherhood Ban Could Upend Turkish-Qatari Strategies

UK £2 Issue 204, Year 5 May 5, 2019 EU €2.50 www.thearabweekly.com Hope after Baghdadi’s Corruption- Spanish first video fuelled unrest elections in five years in the Arab world Page 17 Pages 6,7-9 Page 4 US move towards Brotherhood ban could upend Turkish-Qatari strategies ► Support to Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated groups is a major pillar of Turkey’s and Qatar’s influence strategies in the region. Thomas Seibert in its relations with the United States. Ties are under strain by US support for Kurdish militants in Istanbul Syria, Ankara’s wish to buy Rus- sian military hardware and by plan by members of the Turkey’s determination to pursue US administration to close relations with neighbour designate the Muslim Iran despite the threat of US sanc- A Brotherhood an interna- tions. tional terrorist organisation is ex- Gunter Seufert, a Turkey expert pected to be yet another irritant at the German Institute for Inter- in troubled relations between An- national and Security Affairs, a kara and Washington. think-tank in Berlin, said a desig- The move could also put fresh nation of the Muslim Brotherhood pressure on ties between Wash- as a terrorist group would be “an- ington and Doha. Like Turkey, other point of conflict” between Qatar is a major backer of the Turkey and the United States. Muslim Brotherhood. It is also the “This would harden fronts fur- site of the largest US military base ther,” Seufert said by telephone. in the Middle East. Both Turkish US President Donald Trump’s and Qatari strategies in the region decision to consider putting the could be upended. -

Russia and the War in Syria Moscow Steps up Military Presence in Syria

September 25, 2015 3 Special Focus Russia and the war in Syria Moscow steps up military presence in Syria The Arab Weekly staff Syrian opposition figures and rebel from Turkey and Saudi Arabia to groups dismiss the moves as yet an- serve as the ground forces of the other bid to prop up the regime of US-led coalition. Beirut President Bashar Assad. Some observers say Russia wants Four Russian-made fighter jets the alliance to give the Syrian Army ussia has significantly launched more than a dozen air pride of place because it is familiar ramped up its military strikes against the city of Raqqa on with the demographics and geogra- presence in war-torn September 17th, where the city’s phy of the areas where battles with Syria under the aegis of weary inhabitants were already ISIS are raging and because the fighting Islamic State reeling from months of sorties by regime has sleeper cells in those R(ISIS) jihadists, providing advanced both the Syrian regime and the in- places. air and ground weapons that the ternational coalition mobilised to Syrian Army was quick to employ fight ISIS. Opposition figures against the notorious group. But Hospital sources said 37 people, stress that Russia mostly women and children, were has been heavily killed and 65 others wounded. Lo- cal observers said the firepower involved in the war involved was significantly greater for several years than that previously used by the regime. Entire city blocks were pul- While some opposition figures verised by the new aircraft. stress that Russia has been heav- According to Syrian political ily involved in the war for several sources, the regime has begun us- years, the recent moves do contain ing new Russian weaponry in La- new elements.