James Baldwin's Radicalism and the Evolution of His Thought on Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 9 Article 15 2009 Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement Melissa Seifert Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Seifert, Melissa (2009) "Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Seifert: Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in t Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement By: Melissa Seifert The origins of the Black Power Movement can be traced back to the civil rights movement’s sit-ins and freedom rides of the late nineteen fifties which conveyed a new racial consciousness within the black community. The initial forms of popular protest led by Martin Luther King Jr. were generally non-violent. However, by the mid-1960s many blacks were becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow pace and limited extent of progressive change. -

A Nation of Law? (1968-1971) BOBBY SEALE

A Nation of Law? (1968-1971) BOBBY SEALE: When our brother, Martin King, exhausted a means of nonviolence with his life being taken by some racist, what is being done to us is what we hate, and what happened to Martin Luther King is what we hate. You're darn right, we respect nonviolence. But to sit and watch ourselves be slaughtered like our brother, we must defend ourselves, as Malcolm X says, by any means necessary. WILLIAM O'NEAL: At this point, I question the whole purpose of the Black Panther Party. In my thinking, they were necessary as a shock treatment for white America to see black men running around with guns just like black men saw the white man running around with guns. Yeah, that was a shock treatment. It was good in that extent. But it got a lot of black people hurt. ELAINE BROWN: There was no joke about what was going on, but we believed in our hearts that we should defend ourselves. And there were so many that did do that. NARRATOR: By 1968, the Black Panther Party was part of an increasingly volatile political scene. That summer, the National Democratic Convention in Chicago was disrupted by violent clashes between demonstrators and police. The war in Vietnam polarized the nation and the political and racial upheaval at home soon became an issue in the presidential campaign. PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: This is a nation of laws and as Abraham Lincoln had said, no one is above the law, no one is below the law, and we're going to enforce the law and Americans should remember that if we're going to have law and order. -

Seize the Time: the Story of the Black Panther Party

Seize The Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party Bobby Seale FOREWORD GROWING UP: BEFORE THE PARTY Who I am I Meet Huey Huey Breaks with the Cultural Nationalists The Soul Students Advisory Council We Hit the Streets Using the Poverty Program Police-Community Relations HUEY: GETTING THE PARTY GOING The Panther Program Why We Are Not Racists Our First Weapons Red Books for Guns Huey Backs the Pigs Down Badge 206 Huey and the Traffic Light A Gun at Huey's Head THE PARTY GROWS, ELDRIDGE JOINS The Paper Panthers Confrontation at Ramparts Eldridge Joins the Panthers The Death of Denzil Dowell PICKING UP THE GUN Niggers with Guns in the State Capitol Sacramento Jail Bailing Out the Brothers The Black Panther Newspaper Huey Digs Bob Dylan Serving Time at Big Greystone THE SHIT COMES DOWN: "FREE HUEY!" Free Huey! A White Lawyer for a Black Revolutionary Coalitions Stokely Comes to Oakland Breaking Down Our Doors Shoot-out: The Pigs Kill Bobby Hutton Getting on the Ballot Huey Is Tried for Murder Pigs, Puritanism, and Racism Eldridge Is Free! Our Minister of Information Bunchy Carter and Bobby Hutton Charles R. Garry: The Lenin of the Courtroom CHICAGO: KIDNAPPED, CHAINED, TRIED, AND GAGGED Kidnapped To Chicago in Chains Cook County Jail My Constitutional Rights Are Denied Gagged, Shackled, and Bound Yippies, Convicts, and Cops PIGS, PROBLEMS, POLITICS, AND PANTHERS Do-Nothing Terrorists and Other Problems Why They Raid Our Offices Jackanapes, Renegades, and Agents Provocateurs Women and the Black Panther Party "Off the Pig," "Motherfucker," and Other Terms Party Programs - Serving the People SEIZE THE TIME Fuck copyright. -

Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2007 Radicalism in American Political Thought : Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed Christopher Thomas Cooney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African American Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cooney, Christopher Thomas, "Radicalism in American Political Thought : Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed" (2007). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3238. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3228 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Chri stopher Thomas Cooney for the Master of Science in Political Science were presented July 3 1, 2007, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Cr~ cyr, Chai( David Kinsell a Darrell Millner Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: I>' Ronald L. Tammen, Director Hatfield School of Government ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Christopher Thomas Cooney for the Master of Science in Political Science presented July 31, 2007. Title: Radicalism in American Political Thought: Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed. American Political Thought has presented somewhat of a challenge to many because of the conflict between the ideals found within the "American Creed" and the reality of America's treatment of ethnic and social minorities. -

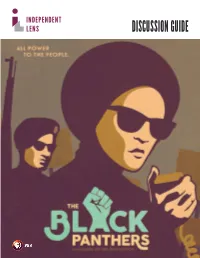

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using this Guide 1 From the Filmmaker 2 The Film 3 Framing the Context of the Black Panther Party 4 Frequently Asked Questions 6 The Black Panther Party 10-Point Platform 9 Background on Select Subjects 10 Planning Your Discussion 13 In Their Own Words 18 Resources 19 Credits 21 DISCUSSION GUIDE THE BLACK PANTHERS Using This Guide This discussion guide will help support organizations hosting Indie Lens Pop-Up events for the film The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, as well as other community groups, organizations, and educators who wish to use the film to prompt discussion and engagement with audiences of all sizes. This guide is a tool to facilitate dialogue and deepen understanding of the complex topics in the film The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. It is also an invitation not only to sit back and enjoy the show, but also to step up and take action. It raises thought-provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply and spark conversations with one another. We present suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also include valuable resources and Indie Lens Pop-Up is a neighborhood connections to organizations on the ground series that brings people together for that are fighting to make a difference. film screenings and community-driven conversations. Featuring documentaries seen on PBS’s Independent Lens, Indie Lens Pop-Up draws local residents, leaders, and organizations together to discuss what matters most, from newsworthy topics to family and relationships. -

Black Panther Party: 1966-1982

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 1-1-2000 Black Panther Party: 1966-1982 Michael X. Delli Carpini University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Delli Carpini, M. X. (2000). Black panther party: 1966-1982. In I. Ness & J. Ciment (Eds.), The encyclopedia of third parties in America (pp. 190-197). Armonke, NY: Sharpe Reference. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/1 NOTE: At the time of publication, the author Michael X. Delli Carpini was affiliated with Columbia University. Currently January 2008, he is a faculty member of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Panther Party: 1966-1982 Abstract The Black Panther party was founded in Oakland, California, in 1966. From its beginnings as a local, community organization with a handful of members, it expanded into a national and international party. By 1980, however, the Black Panther party was once again mainly an Oakland-based organization, with no more than fifty active members. In 1982, the party came to an official end. Despite itselativ r ely short history, its modest membership, and its general eschewing of electoral politics, the Black Panther party was arguably the best known and most controversial of the black militant political organizations of the 1960s, with a legacy that continues to this day. -

All Power to the People: the Black Panther Party As the Vanguard of the Oppressed

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AS THE VANGUARD OF THE OPPRESSED by Matthew Berman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in American Studies Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida May 2008 ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AS THE VANGUARD OF THE OPPRESSED by Matthew Berman This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Christopher Strain, and has been approved by the members of her/his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Christopher Strain ____________________________ Dr. Laura Barrett ______________________________ Dean, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Author would like to thank (in no particular order) Andrew, Linda, Kathy, Barbara, and Ronald Berman, Mick and Julie Grossman, the 213rd, Graham and Megan Whitaker, Zach Burks, Shawn Beard, Jared Reilly, Ian “Easy” Depagnier, Dr. Strain, and Dr. Barrett for all of their support. I would also like to thank Bobby Seale, Fred Hampton, Huey Newton, and others for their inspiration. Thanks are also due to all those who gave of themselves in the struggle for showing us the way. “Never doubt that a small group of people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead iii ABSTRACT Author: Matthew Berman Title: All Power to the People: The Black Panther Party as the Vanguard of the Oppressed Institution: Wilkes Honors College at Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. -

The Opportunity and Peril of African-American Reparations Alfreda Robinson

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 24 Issue 1 Healing the Wounds of Slavery: Can Present Article 8 Legal Remedies Cure Past Wrongs? 1-1-2004 Troubling "Settled" aW ters: The Opportunity and Peril of African-American Reparations Alfreda Robinson Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Recommended Citation Alfreda Robinson, Troubling "Settled" Waters: The Opportunity and Peril of African-American Reparations, 24 B.C. Third World L.J. 139 (2004), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol24/ iss1/8 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TROUBLING "SETTLED" WATERS: THE OPPORTUNITY AND PERIL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN REPARATIONS ALFREDA ROBINSON* Abstract: This Article explores the theme of "troubling settled waters," which represents the impact of African-American reparations on the current landscape of race relations in America. The Article outlines the current and historical debate over reparations, addressing the arguments of opponents who contend that reparations dialogue and action wastes intellectual and monetary resources, unnecessarily resurrects painful memories, and creates racial division. It also takes note of contemporary reparations efforts in the courts. as well as the theories and bases for this litigation. The Article concludes that, given the continuing pervasiveness of race and race issues in IHodern runerica, reparations are a welcome and important opportunity for achieving civil rights goals. -

Heresy in 1600 Q 329

Index of Transcribed Tapes Prepared by The Jonestown Institute (https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703) Key: Red type = Public figures/National and international names/Individuals not in Temple Blue type = Radio codes * = Voice on tape † = Died on November 18, 1978 [Notes at end] A Abedi, Agha Hasan, founder of BCCI bank in London Q 745 Abel, I.W., president of the United Steel Workers Q 153 Abercrombie, Hal, teacher at Opportunity High Q 735 Abernathy, Ralph, Civil rights worker, president of Southern Christian Leadership Conference Q 211, Q 314, Q 381, Q 382, Q 968, Q 1053-4 Abigail (reference seemingly to stateside person) Q 592 Abourezk, James, U.S. Senator, Democrat from South Dakota Q 49a, Q 198, Q 259, Q 289, Q 294, Q 314, Q 398 Abruzzo, Benjamin L., captain of the balloon Double Eagle Q 398 Ackman, Margaret, leader in Guyana’s People’s National Congress Q 50, Q 161, Q 322 Adams, John, former U.S. president Q 238 Adams, John, supporter of Dennis Banks Q 614 Adams, Norman, Guyanese official Q 724 Adams, Odell, Guyanese attorney Q 241 Adams, Paula Q 51, Q 197, Q 245*, Q 268, Q 347, Q 569, Q 570, Q 573, Q 588, Q 590, Q 598, Q 606, Q 639, Q 640, Q 662, Q 678, Q 705*, Q 781, Q 833*, Q 868 [in code], Q 933, Q 1058-3 (See also, Paula) Adams, Tom (See also, Tom) Q 708, Q 757, Q 900* Addonozio, Hugh, former Mayor of Newark, New Jersey Q 737 Adefope, Henry, Nigerian Foreign Minister Q 309 †Addison, Steve (See also, Steve ) Q 182, Q 242, Q 594*, Q 993, Q 1055-2 Aemilianus, Scipio Q 742 Africanus, Leo, map maker and explorer Q 742 Africanus, Scipio, military commander Q 742 Afshar, Amir Khosrow, Iranian Foreign Minister Q 266 Agee, Philip, former CIA agent, critic of agency Q 176, Q 184, Q 309, Q 342, Q 397 Agnes (See also, Jones, Agnes) Q 454 Agnew, Spiro, Vice President of U.S. -

Oral History Bobby Seale

Student Handout Oakland Museum of California What’s Going On? California and the Vietnam Era Lesson Plan #2 1968: Year of Social Change and Turning Point in Vietnam and the U.S. Oral History Bobby Seale Bobby Seale was a leader of the Black Panther Party. … establishment press picture with Huey and I standing in front of our Black Panther Party office at 5624 Grove Street. I lived at 57th and Grove. I lived on 57th, so it was a block or so away from my home. And I had rented that office there. But my point is I have that Army .45 in a holster, but it’s hanging over my shoulder—the belt that you would turn around your waist is hanging over my shoulder. And Huey has a high- standing shotgun that, uh, I bought. It was an $89 deal I bought that high-standing shotgun with one of my paychecks from the North Oakland Neighborhood Service Center. And I was still employed at the North Oakland Neighborhood Service Center for the city government, but, uh, that’s what we did. And we took and recruited—it took two months to recruit 14 people. Interviewer: How did you get the name, “Black Panther Party”? Oh, that’s right. I’m sorry. The Black Panther Party—the naming of the organization, the real original name of the Black Panther Party was the Black Panther Party for Self- Defense. But we had written a ten-point platform and program and it took a week to get everything refined. And one day I had received mail from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization down south, where voting rights were going on with the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. -

Black Panthers Point Plan

in Oakland, they might stop the Party dressed in all black. you and begin sharing their Ten They wore black berets, a black Black Panthers Point Plan. leather jacket, a dark shirt and Huey Newton and Bobby Seale started an organi- black pants, and usually had zation to help Africans and stop police violence. TEN POINT PLAN shinny black shoes. They also n Oakland, two men met at Merritt carried handguns and shotguns ICollege in 1966, to share their 1. We want freedom. We want power as they moved through the ideas about how to help Africans in to determine the destiny of our Black community, declaring with Oakland. The two men were Huey P. Community. fi sts raised, "Power to the Newton and Bobby Seale. They 2. We want full employment for our People!" had known each other for months people. and one day they decided to form 3. We want an end to the robbery They quickly expanded beyond a new organization. They sat down by the white man of our Black Oakland, and soon there were for an hour and wrote the ideas for Community. Black Panther chapters all their new group - their ideas formed 4. We want decent housing, fi t for over America in cities such as the "Ten Point Plan", and they shelter of human beings. Chicago, Detroit, and New York. took the name, the “Black Panther 5. We want education that teaches The chapters worked together, Party for Self Defense”. It was no us our true history and our role in the and shared information and present-day society. -

Admixture of Socio-Personal History in the Biographies of the Black Panthers

Vol. 4(10), pp. 473-479, December, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2012.0371 International Journal of English and ISSN 2141-2626 © 2013 Academic Journals Literature http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Review Admixture of socio-personal history in the biographies of The Black Panthers Sehgal Srishti Department of English and Cultural Studies, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India. Accepted 11 May, 2013 The paper is an endeavour to study the revolution brought about by the Black Panther Party through a detailed study of the two autobiographies: ‘Revolutionary Suicide’ by Huey P. Newton and ‘Seize the Time’ by Bobby Seale. Formed in 1966, in the United States of America, The Black Panther Party for self-defence was a revolutionary organisation that served the community. The Black Panther Party was not only political, but a counter cultural movement which brought about a revolution in art and literature as well. It was an iconic counter cultural movement which became the seat of revolutionary ideas. Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale were the founders of the party. The Panthers were such an organization that inspired many following generations to rise in struggle against the oppressive system. They achieved this by systematic resistance through the tools of literature, rewriting history, development of political aesthetics, but above all, a personal commitment to the organization of African-Americans. The autobiographies of the two leaders of the party, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale can provide vital insights into the revolution which strived to bring about a change in the status of African-Americans. Key words: The Black Panther Party, autobiographies, counter culture, literature as a tool for revolution, African-American Revolution.