Calder and Mondrian: an Unlikely Kinship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Liberale Opmars

ANDRÉ VERMEULEN Boom DE LIBERALE OPMARS André Vermeulen DE LIBERALE OPMARS 65 jaar v v d in de Tweede Kamer Boom Amsterdam De uitgever heeft getracht alle rechthebbenden van de illustraties te ach terhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen dat uw rechten niet zijn gehonoreerd, dan kunt u contact opnemen met Uitgeverij Boom. Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonde ringen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part ofthis book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the writtetj permission of the publisher. © 2013 André Vermeulen Omslag: Robin Stam Binnenwerk: Zeno isbn 978 90 895 3264 o nur 680 www. uitgeverij boom .nl INHOUD Vooraf 7 Het begin: 1948-1963 9 2 Groei en bloei: 1963-1982 55 3 Trammelant en terugval: 1982-1990 139 4 De gouden jaren: 1990-2002 209 5 Met vallen en opstaan terug naar de top: 2002-2013 De fractievoorzitters 319 Gesproken bronnen 321 Geraadpleegde literatuur 325 Namenregister 327 VOORAF e meeste mensen vinden politiek saai. De geschiedenis van een politieke partij moet dan wel helemaal slaapverwekkend zijn. Wie de politiek een beetje volgt, weet wel beter. Toch zijn veel boeken die politiek als onderwerp hebben inderdaad saai om te lezen. Uitgangspunt bij het boek dat u nu in handen hebt, was om de geschiedenis van de WD-fractie in de Tweede Kamer zodanig op te schrijven, dat het trekjes van een politieke thriller krijgt. -

De VVD Visueel Voerman, Gerrit

University of Groningen De VVD visueel Voerman, Gerrit IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2008 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Voerman, G. (2008). De VVD visueel: Liberale affiches in de twintigste eeuw. Boom. https://www.uitgeverijboom.nl/boeken/geschiedenis/de_vvd_visueel_9789085065395/ Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 04-10-2021 de vvd visueel gerrit voerman Met medewerking van Lucas Osterholt de vvd visueel Liberale affiches in de twintigste eeuw boom amsterdam © 2008 Gerrit Voerman, Groningen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uit- zonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of open- baar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. -

Frits Bolkestein Is Een Leergierig Ventje Van Veertien Jaar En

1 HET BEGIN: 1948-1963 rits Bolkestein is een leergierig ventje van veertien jaar en zit in de tweede klas van het prestigieuze Barlaeus Gymnasium Fin Amsterdam, Neelie Kroes speelt in Rotterdam op de kleu terschool, niet met poppen maar met houten vrachtautootjes, en ook Hans Wiegel vermaakt zich nog in de zandbak, terwijl Ed Nijpels nog geboren moet worden. Terwijl deze kinderen nog geen flauwe notie hebben van de roem die zij later in politiek en bestuur zullen vergaren, loopt de 21-jarige Schilleman Overwa ter het Amsterdamse Centraal Station uit. Het is zaterdag 24 ja nuari 1948. De snijdende en harde oostenwind maakt het met een paar graden boven nul onaangenaam koud. Gevoelstemperatuur min vijf, zouden we nu zeggen. De jongeman uit het Zuid-Hol- landse dorpje Strijen trekt zijn kraag hoog op, steekt zijn handen diep in zijn jaszakken en loopt naar de halte van lijn 1. De tram staat gelukkig al klaar en negen haltes verder stapt hij uit op het Leidseplein. Overwater heeft van tevoren goed geïnformeerd hoe hij bij Theater Bellevue moet komen; hij kent de hoofdstad niet. Het is gaan sneeuwen, grote, natte vlokken, en dat zal nog uren zo doorgaan. Gelukkig hoeft hij niet ver te lopen. Hij wandelt langs hotel-restaurant Americain, slaat rechts af de Leidselcade op en betreedt even later het zalencomplex waar ruim twaalf jaar eerder Max Euwe wereldkampioen schaken is geworden tegen de Rus Aljechin. 9 Een week daarvoor is O ver water voor het eerst van zijn leven in Amsterdam. Zijn Partij van de Vrijheid (PvdV) heeft er ver gaderd over samenwerking met het Comité-Oud. -

De Liberale Opmars 65 Jaar VVD in De Tweede Kamer

André Vermeulen DE LIBERALE OPMARS 65 jaar VVD in de Tweede Kamer Boom Amsterdam De uitgever heeft getracht alle rechthebbenden van de illustraties te ach- terhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen dat uw rechten niet zijn gehonoreerd, dan kunt u contact opnemen met Uitgeverij Boom. Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonde- ringen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. © 2013 André Vermeulen Omslag: Robin Stam Binnenwerk: Zeno ISBN 978 90 895 3264 0 NUR 680 www.uitgeverijboom.nl INHOUD Vooraf 7 1 Het begin: 1948-1963 9 2 Groei en bloei: 1963-1982 55 3 Trammelant en terugval: 1982-1990 139 4 De gouden jaren: 1990-2002 209 5 Met vallen en opstaan terug naar de top: 2002-2013 253 De fractievoorzitters 319 Gesproken bronnen 321 Geraadpleegde literatuur 325 Namenregister 327 VOORAF e meeste mensen vinden politiek saai. De geschiedenis van een politieke partij moet dan wel helemaal slaapverwekkend Dzijn. Wie de politiek een beetje volgt, weet wel beter. Toch zijn veel boeken die politiek als onderwerp hebben inderdaad saai om te lezen. Uitgangspunt bij het boek dat u nu in handen hebt, was om de geschiedenis van de VVD-fractie in de Tweede Kamer zodanig op te schrijven, dat het trekjes van een politieke thriller krijgt. -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar Visie Ontbreekt, Komt

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar visie ontbreekt, komt het volk om Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar visie ontbreekt, komt het volk om Redactie: Carla van Baalen Hans Goslinga Alexander van Kessel Johan van Merriënboer Jan Ramakers Jouke Turpijn Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Boom – Amsterdam Foto omslag: Paul Babeliowsky / Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Vormgeving: Boekhorst Design B.V., Culemborg © 2011 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem- ming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 978 94 6105 546 0 nur 680 www.uitgeverijboom.nl Inhoud Ten geleide 9 Artikelen Henri Beunders, De terugkeer van de klassenstrijd. De angst van de visieloze burgerij 15 voor ‘de massa’ lijkt op die van rond 1900 Patrick van Schie, Ferm tegenspel aan ‘flauwekul’. De liberale politiek-filosofische 29 inbreng in het Nederlandse parlement: voor individuele vrijheid en evenwichtige volksinvloed Arie Oostlander, Aan Verhaal geen gebrek. Over de noodzaak van een betrouwbaar 41 kompas voor het cda Paul Kalma, Het sociaaldemocratisch program… en hoe het in de verdrukking kwam 53 Erie Tanja, ‘Dragers van beginselen.’ De parlementaire entree van Abraham Kuyper en 67 Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis Koen Vossen, Een Nieuw Groot Verhaal? Over de ideologie van lpf en pvv 77 Hans Goslinga en Marcel ten Hooven, ‘De vraag is of de democratie blijvend is.’ Interview 89 met J.L. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

De Wederopbouw Van Rotterdam

De wederopbouw van Rotterdam www.bibliotheek.rotterdam.nl Inleiding Wederopbouw Rotterdam Wederopbouw is het begrip dat gebruikt wordt voor de herbouw van Nederland na de Deze maand ziet de kalender er iets anders uit dan jullie gewend zijn: deze speciale verwoestingen van de Tweede Wereldoorlog. In de architectuur en stedenbouw betreft editie staat in het teken van de wederopbouw van Rotterdam. Het afgelopen jaar het vooral de periode van 1945 tot ongeveer 1968. Rotterdam is dé Wederopbouwstad hebben wij veel gesprekken gevoerd met jullie en we merkten dat er veel mooie van Nederland. Hier is de wederopbouw het best zichtbaar, vooral in het centrum. verhalen waren over vroeger en dat bracht ons op het idee een oproep te plaatsen om Door het bombardement van 14 mei 1940 was het hart van de stad verwoest. Maar ook deze verhalen te delen. Wat zijn jullie ervaringen in de periode van de wederopbouw? andere steden als Middelburg, Arnhem, Nijmegen en Den Helder werden zwaar getrof- De maand mei staat in het teken van de wederopbouw. 18 mei is de symbolische fen. Rotterdam heeft de wederopbouw het meest rigoureus aangepakt en de nieuwe datum voor het vieren van de wederopbouw. Dit is de dag waarop stadsarchitect ideeën over de functionele stad het meest consequent toegepast. Rotterdam stond niet W.G. Witteveen in 1940 de opdracht kreeg voor zijn wederopbouwplan. bekend om zijn stadsschoon, dus er werd zoveel geruimd dat er ruimte ontstond voor een nieuwe, betere, mooiere stad. Tijdens de bezetting kwam de wederopbouw niet boek. Vele fotografen maakten in opdracht foto- van de grond. -

Reflections on Dutch Political Discourse

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. https://hdl.handle.net/2066/214853 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-01 and may be subject to change. the author(s) 2019 ISSN 1473-2866 (Online) ISSN 2052-1499 (Print) www.ephemerajournal.org volume 19(3): 487-512 On the (ab)use of the term ‘neoliberalism’: Reflections on Dutch political discourse Lars Cornelissen abstract This article raises some questions about the role assumed by the methodological debate surrounding the usefulness of the term ‘neoliberalism’ in relation to the broader realm of political discourse. I contend that this debate cannot be settled on an analytical register and that questions surrounding the use and abuse of the term ‘neoliberalism’ must be situated carefully with regard to specific political contexts, literatures and organisations. When we fail to do so, we risk our words being mobilised by ideologically partisan intellectuals in an attempt to interrupt the critical analysis of neoliberalism. In order to argue my case I provide a detailed discussion of the history of Dutch neoliberal politics, followed by a discussion of the history of Dutch uses of the term ‘neoliberalism’. I demonstrate that, in the context of Dutch politics, neoliberal intellectuals have in recent years been able to mobilise the scholarly debate on the analytical value of the term ‘neoliberalism’ in order to deny the existence of their own ideology. I conclude that, in the Dutch context, the stakes of this debate are different from the Anglophone setting and that what is needed in the former is rigorous historical analysis rather than an abstract methodological discussion. -

Re-Reading Dutch Architecture in Relation to Social Issues from the 1940S to the 1960S

Re-reading Dutch Architecture in Relation to Social Issues from the 1940s to the 1960s Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning Volume 14, June 2018 Re-reading Dutch Architecture in Relation to Social Issues from the 1940s to the 1960s Pat Seeumpornroj Faculty of Architecture, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand [email protected] ABSTRACT his paper seeks to connect the work of J.J.P. Oud, Aldo van Eyck, and Herman Hertzberger, the three T Dutch protagonists to the dominant social issues that occurred from the 1940s to the 1960s. They addressed the following issues: poverty, the housing shortages from the pre-World War II period, the sociopolitical issues in the collective expression of the public, rapid economy recovery, large population growth, and white-collar labor in the post-World War II period. The author will examine the role played by the Dutch government in advancing a progressive social agenda, and will demonstrate both continuities and discontinuities between them. Keywords: J.J.P. Oud, Aldo van Eyck, Herman Hertzberger, Dutch modernism, architecture culture INTRODUCTION one could say that the architectural community in the Netherlands was more open to the fresh ideas of In the aftermath of World War II, Dutch Modernism younger generations than in other countries. Via the began to catch world attention, and its architectural history, young architects unconsciously learned the movements were widely discussed in English rebellious culture in architecture. Therefore, in this writings, both its mainstream and rebellion in study, the focus is on the architectural discourses of architecture discourses. Mainstream refers to rebellion and their representative projects in relation buildings related to the ‘quantity’ of the post-war to social issues that occurred from the 1940s to the reconstruction and projects influenced by American 1960s. -

University of Groningen the Incoming Tide Hollander, Jieskje

University of Groningen The incoming tide Hollander, Jieskje IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2013 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Hollander, J. (2013). The incoming tide: Dutch reactions to the constitutionalisation of Europe. Groningen: s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 The Incoming Tide A commercial edition of this thesis will be published in summer 2013. Title: ‘Constitutionalising Europe. Dutch Reactions to an Incoming Tide.’ isbn: 978 90 8952 139 2 Publisher: Europa Law Publishing Copyright © Jieskje Hollander, 2013 Design Joost Dekker i.s.m. de ontwerpvloot Printed by Proefschriftmaken.nl | Uitgeverij BOXPress Published by Uitgeverij BOXPress, ’s-Hertogenbosch This work is part of the research programme Contested Constitutions, which is financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (nwo). -

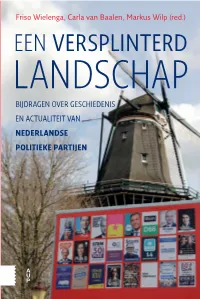

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

In Tijden Van Crisis

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2009 In tijden van crisis Boom Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2009 In tijden van crisis Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis In van crisis Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld M.H.C.H. Leenders J.C.F.J. van M erriënboer J.J.M. Ramakers J.J.B. Turpijn Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Boom - Amsterdam Foto omslag: Martijn Beekman, Den Haag Omslag en binnenwerk: Boekhorst Design, Culemborg © 2009 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem ming van de uitgever. No part ofthis book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 978 90 8506 806 8 nur 680,697 www.uitgeverijboom.nl Inhoud Lijst van afkortingen 7 Ten geleide 11 Artikelen 13 Uri Rosenthal, Crises en parlementaire bemoeienis. Hoe de regering regeert, het heft in 15 handen houdt en de Kamer het nakijken geeft Hardy Beekelaar, Uitvinding en herijking. Crises in het Nederlandse politieke bestel 27 tussen 1795 en 1848 Herman Langeveld, Grotendeels buitenspel. Het Nederlandse parlement en de crisis 37 van de jaren dertig van de twintigste eeuw Ruud Koole, Le culte de 1’incompétence! Antipolitiek, populisme en de kritiek op het 47 Nederlandse parlementaire stelsel Peter van Griensven, De zure appel in tijden van economische crisis 59 Jan Ramakers en Jouke Turpijn, De Crisiscanon 73 Bert van den Braak, Geen zelfreflectie, maar zelfbewustzijn.