Economic Contribution Analysis of Sc’S Forestry Sector, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Timber Forest Products

Agrodok 39 Non-timber forest products the value of wild plants Tinde van Andel This publication is sponsored by: ICCO, SNV and Tropenbos International © Agromisa Foundation and CTA, Wageningen, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. First edition: 2006 Author: Tinde van Andel Illustrator: Bertha Valois V. Design: Eva Kok Translation: Ninette de Zylva (editing) Printed by: Digigrafi, Wageningen, the Netherlands ISBN Agromisa: 90-8573-027-9 ISBN CTA: 92-9081-327-X Foreword Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are wild plant and animal pro- ducts harvested from forests, such as wild fruits, vegetables, nuts, edi- ble roots, honey, palm leaves, medicinal plants, poisons and bush meat. Millions of people – especially those living in rural areas in de- veloping countries – collect these products daily, and many regard selling them as a means of earning a living. This Agrodok presents an overview of the major commercial wild plant products from Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific. It explains their significance in traditional health care, social and ritual values, and forest conservation. It is designed to serve as a useful source of basic information for local forest dependent communities, especially those who harvest, process and market these products. We also hope that this Agrodok will help arouse the awareness of the potential of NTFPs among development organisations, local NGOs, government officials at local and regional level, and extension workers assisting local communities. Case studies from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Central and South Africa, the Pacific, Colombia and Suriname have been used to help illustrate the various important aspects of commercial NTFP harvesting. -

Effect of Wood Preservative Treatment of Beehives on Honey Bees Ad Hive Products

1176 J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984. 32, 1176-1180 Effect of Wood Preservative Treatment of Beehives on Honey Bees and Hive Products Martins A. Kalnins* and Benjamin F. Detroy Effects of wood preservatives on the microenvironment in treated beehives were assessed by measuring performance of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies and levels of preservative residues in bees, honey, and beeswax. Five hives were used for each preservative treatment: copper naphthenate, copper 8-quinolinolate, pentachlorophenol (PCP), chromated copper arsenate (CCA), acid copper chromate (ACC), tributyltin oxide (TBTO), Forest Products Laboratory water repellent, and no treatment (control). Honey, beeswax, and honey bees were sampled periodically during two successive summers. Elevated levels of PCP and tin were found in bees and beeswax from hives treated with those preservatives. A detectable rise in copper content of honey was found in samples from hives treated with copper na- phthenate. CCA treatment resulted in an increased arsenic content of bees from those hives. CCA, TBTO, and PCP treatments of beehives were associated with winter losses of colonies. Each year in the United States, about 4.1 million colo- honey. Harmful effect of arsenic compounds on bees was nies of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) produce approxi- linked to orchard sprays and emissions from smelters in mately 225 million pounds of honey and 3.4 million pounds a Utah study by Knowlton et al. (1947). An average of of beeswax. This represents an annual income of about approximately 0.1 µg of arsenic trioxide/dead bee was $140 million; the agricultural economy receives an addi- reported. -

A Vision for Forest Products Extension in Wisconsin

Wisconsin’s Forest Industry: Rooted in our Lives Rooted in our Economy Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Forestry Division, Forest Products Services Wisconsin forest industry overview Industry sectors and trends Emerging markets Part I: Forest Industry Overview Wisconsin’s forest industry ~1,200 establishments Over 60,000 jobs $24.1 billion in goods and services annually Approximately 14% of manufacturing jobs Wisconsin’s forest industry (cont’d) Exports total over $2.2 billion annually Top employer in 10 counties Supports employment of over 111,000 additional jobs Why should we care? . The health of Wisconsin’s economy depends upon the health of Wisconsin’s forest industry . The health of Wisconsin’s forests depends upon the health of Wisconsin’s forest industry Why should we care? . We as consumers depend on forests! Flooring Baseball bats Houses Ice cream thickener Lumber Garden stakes Furniture Toilet paper Pressboard Charcoal Crafts Broom sticks Veneer Bowling pins Roofs Imitation bacon Plywood Toys Stairways Candy wrappers Dowels Signs Cider Fruit Paper Syrup Vitamins Cutting boards Paneling Pallets Cooking utensils Desks Windows Cardboard Pencils Food packaging Doors Grocery bags Shampoo Toilet seats Railroad ties Chewing gum Oars Toothpaste Energy Paper towels Coffee filters Nuts Firewood Oil spill agents Toothpicks Magazines Christmas trees Hockey sticks Diapers Golf tees Tool handles Liquid smoke Sponges Nail polish Animal bedding Cosmetics Mulch Wood pellets Fence posts Baby foods Postage stamps AND MORE! Can -

Trends in Creosote Supply and Quality by Richard Harris, Koppers Industries

Trends in Creosote Supply and Quality by Richard Harris, Koppers Industries Introduction This paper examines the ten-year outlook for wood-preserving creosotes in North America. The major factors determining creosote availability and quality in the future will be the quantity of coal tar produced in the United States, and the economics of the competing uses for coal tar distillates. Major Uses of Coal Tar Distillates Though no two tar plants are exactly alike, in general we may say that two distillate streams are initially generated during the production of coal tar pitch (see chart). The first distillate off, representing 20 percent of the tar, is generally known as chemical oil. It is the fighter fraction, containing from 40 to 55 percent naphthalene. The second, heavier distillate is the creosote fraction used to make wood preservative and carbon black. It accounts for 30 percent of the crude tar. The remainder, about half of the tar is carbon pitch for the aluminum and graphite industries. This is the product which drives the domestic tar distillation business. Each distillate may then be processed to create value-added products. Solvent from which resins are made, naphthalene for plastics and pesticides, and "correction oil" for use in wood-preserving creosote are all derived from the chemical oil. In North America, most of the creosote fraction produced is combined with correction oil, or in some instances unprocessed chemical oil, to make AWPA-specification creosotes. The heavy distillate left over after wood preserving needs are met is sold as carbon black feedstock. In the rest of the world, this fraction is mostly used for the production of carbon black and anthracene oil. -

History and Recent Trends

Contents Part I Setting 1 Working Landscapes of the Spanish Dehesa and the California Oak Woodlands: An Introduction.......... 3 Lynn Huntsinger, Pablo Campos, Paul F. Starrs, José L. Oviedo, Mario Díaz, Richard B. Standiford and Gregorio Montero 2 History and Recent Trends ............................. 25 Peter S. Alagona, Antonio Linares, Pablo Campos and Lynn Huntsinger Part II Vegetation 3 Climatic Influence on Oak Landscape Distributions........... 61 Sonia Roig, Rand R. Evett, Guillermo Gea-Izquierdo, Isabel Cañellas and Otilio Sánchez-Palomares 4 Soil and Water Dynamics .............................. 91 Susanne Schnabel, Randy A. Dahlgren and Gerardo Moreno-Marcos 5 Oak Regeneration: Ecological Dynamics and Restoration Techniques......................................... 123 Fernando Pulido, Doug McCreary, Isabel Cañellas, Mitchel McClaran and Tobias Plieninger 6 Overstory–Understory Relationships ...................... 145 Gerardo Moreno, James W. Bartolome, Guillermo Gea-Izquierdo and Isabel Cañellas ix x Contents 7 Acorn Production Patterns ............................. 181 Walter D. Koenig, Mario Díaz, Fernando Pulido, Reyes Alejano, Elena Beamonte and Johannes M. H. Knops Part III Management, Uses, and Ecosystem Response 8 Effects of Management on Biological Diversity and Endangered Species ............................... 213 Mario Díaz, William D. Tietje and Reginald H. Barrett 9 Models of Oak Woodland Silvopastoral Management ......... 245 Richard B. Standiford, Paola Ovando, Pablo Campos and Gregorio Montero 10 Raising Livestock in Oak Woodlands ..................... 273 Juan de Dios Vargas, Lynn Huntsinger and Paul F. Starrs 11 Hunting in Managed Oak Woodlands: Contrasts Among Similarities ................................... 311 Luke T. Macaulay, Paul F. Starrs and Juan Carranza Part IV Economics 12 Economics of Ecosystem Services ........................ 353 Alejandro Caparrós, Lynn Huntsinger, José L. Oviedo, Tobias Plieninger and Pablo Campos 13 The Private Economy of Dehesas and Ranches: Case Studies ... -

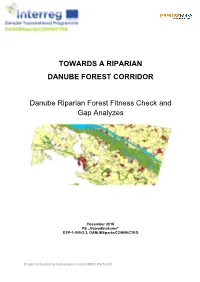

Danube Riparian Forest Corridor Fitness Check and Gap Analyses

TOWARDS A RIPARIAN DANUBE FOREST CORRIDOR Danube Riparian Forest Fitness Check and Gap Analyzes December 2018 PE „Vojvodinašume“ DTP-1-005-2.3, DANUBEparksCONNECTED Project co-funded by the European Union (ERDF, IPA funds) Table of Content 1. INTRODUCTION 2. PURPOSE OF THE DOCUMENT AND METHODOLOGY FOR ITS ELABORATION 3. GEOGRAPHICAL SCOPE 4. LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR DANUBE FOREST HABITAT CORRIDOR 5. DANUBE RIPARIAN FOREST FITNESS CHECK 5.1 Remote Land Service and GIS offise setting up 5.1.1 Cooperation platform with European Environmental Agency 5.1.2 Remote Land Service, GIS tools and GIS interpretation and gap analyses of Copernicus Monitoring Services 5.1.3 Methodology and objectives of the Fitness Check 5.1.3.1 Land use 5.1.3.2 Fragmentation, infrastructure and patchiness (patch cohesion) 5.1.3.3 Wilderness 5.1.3.4 Environmental protection (Protected areas) 5.1.3.5 Hydrological conditions, habitat patches/corridor/habitat network, Dead wood 5.1.3.6 Historic forms of forestry 5.1.3.7 Biodiversity 5.1.3.8 Population 5.1.4 Illustrative map of Riparian zones and forests along the Danube 6. LITERATURE AND REFERENCES Project co-funded by the European Union (ERDF, IPA funds) 1. INTRODUCTION Riparian forests are habitats serving multiple functions for flora, fauna and humans. In the past century, around 90% of the original Danube wetlands have been lost due to human activities. Today, most of the last remaining large-scale floodplain forest complexes are protected by the Danube Protected Areas, famous for their richness in biodiversity. Riparian forests are of great ecological importance, playing an important role in both nature and human populations. -

Longleaf Pine: an Annotated Bibliography, 1946 Through 1967

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Research Paper SO-35 longleaf pine: an annotated bibliography, 1946 through 1967 Thomas C. Croker, Jr. SOUTHERN FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION T.C. Nelson, Director FOREST SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 1968 Croker, Thomas C., Jr. 1968. Longleaf pine: an annotated bibliography, 1946 through 1967. Southern Forest Exp. Sta., New Orleans, Louisiana. 52 pp. (U. S. Dep. Agr. Forest Serv. Res. Pap. SO-35) Lists 665 publications appearing since W. G. Wahlenberg compiled the bibliography for his book, Longleaf Pine. Contents Page Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Factors of the environment. Biology........................................................................................ 2 11 Site factors, climate, situation, soil ............................................................................. 2 15 Animal ecology. Game management .......................................................................... 2 16 General botany ............................................................................................................. 2 17 Systematic botany ....................................................................................................... 6 18 Plant ecology................................................................................................................. 7 2. Silviculture............................................................................................................................... -

Pre-Feasibility Study for a Pulpwood Using Facility Siting in the State Of

Wisconsin Wood Marketing Team July 31, 2020 Pre-Feasibility Study for a Pulpwood-Using Facility Siting in the State of Wisconsin Project Director: Donald Peterson Funded by: State of Wisconsin U.S. Forest Service Wood Innovations Table of Contents Project Team ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview ....................................................................................................... 12 Scope ....................................................................................................................................................... 13 Assessment Process ................................................................................................................................ 14 Identify potential pulp and wood composite panel technologies ...................................................... 15 Define pulpwood availability ............................................................................................................. -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in the Sundarbans

Non-timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in the Sundarbans Fatima Tuz Zohora1 Abstract The Sundarbans is the largest single block of tidal halophytic mangrove forest in the world. The forest lies at the feet of the Ganges and is spread across areas of Bangladesh and West Bengal, India, forming the seaward fringe of the delta. In addition to its scenic beauty, the forest also contains a great variety of natural resources. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) play an important role in the livelihoods of local people in the Sundarbans. In this paper I investigate the livelihoods and harvesting practices of two groups of resource harvesters, the bauwalis and mouwalis. I argue that because NTFP harvesters in the Sundarbans are extremely poor, and face a variety of natural, social, and financial risks, government policy directed at managing the region's mangrove forest should take into consideration issues of livelihood. I conclude that because the Sundarbans is such a sensitive area in terms of human populations, extreme poverty, endangered species, and natural disasters, co-management for this site must take into account human as well as non-human elements. Finally, I offer several suggestions towards this end. Introduction A biological product that is harvested from a forested area is commonly termed a "non-timber forest product" (NTFP) (Shackleton and Shackleton 2004). The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines a non-timber forest product (labeled "non-wood forest product") as "A product of biological origin other than wood derived from forests, other wooded land and trees outside forests" (FAO 2006). For the purpose of this paper, NTFPs are identified as all forest plant and animal products except for timber. -

Nontimber Forest Products in the United States: an Analysis for the 2015 National Sustainable Forest Report

United States Department of Agriculture Nontimber Forest Products in the United States: An analysis for the 2015 National Sustainable Forest Report James Chamberlain, Aaron Teets, and Steve Kruger Forest Service Southern Research Station e-General Technical Report SRS-229, February 2018 Authors: James Chamberlain is a research forest products technologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Forest Inventory & Analysis, 1710 Research Center Drive, Blacksburg, VA 24060, phone (540) 231-3611; Aaron Teets, formerly a research assistant with Conservation Management Institute, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24060, is currently with the University of Maine, School of Forest Resources, Orono, ME 04469; and Steve Kruger is a Ph.D. candidate at Virginia Tech, Forest Resources & Environmental Conservation Department, College of Natural Resources & Environment, Blacksburg, VA 24060. February 2018 Southern Research Station 200 W.T. Weaver Blvd. Asheville, NC 28804 www.srs.fs.usda.gov Nontimber Forest Products in the United States: An analysis for the 2015 National Sustainable Forest Report James Chamberlain, Aaron Teets, and Steve Kruger CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 Nontimber Forest Products .................................................................................................... -

Farm Forestry in Mississippi

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Bulletins Experiment Station (MAFES) 6-1-1946 Farm forestry in Mississippi Mississippi State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/mafes-bulletins Recommended Citation Mississippi State University, "Farm forestry in Mississippi" (1946). Bulletins. 410. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/mafes-bulletins/410 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station (MAFES) at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BULLETIN 432 JUNE, 1946 FARM FORESTRY IN MISSISSIPPI mm Complied by D. W. Skelton, Coordinator Researcli Informa- tion jointly representing Mississippi State Vocational Board and : Mississippi Agricultural Experiment Station MISSISSIPPI STATE COLLEGE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION CLARENCE DORMAN, Director STATE COLLEGE MISSISSIPPI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments are made to Mr. Monty Payne, Head, Depart- ment of Forestry, Mississippi State College, School of Agriculture and Experiment Station, and his staff, Mr. R. T. ClaDp. Mr. E. G. Roberts, Mr. G. W. Abel, and Mr. W. C. Hopkins, for checking the technical content and assisting in the organization of this bulletin; to Mr. V. G. Martin, Head, Agricultural Education Department, State Corege, Mississippi, for his suggestions and assistance in the or- ganization of this bulletin ; to forest industries of Mississippi ; Ex- tension Service, State College, Mississippi ; Texas Forest Service, College Station, Texas ; United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C. ; and Mr. Monty Payne, State College, Mississippi, for photographs used in this bulletin and to all others who made contributions in any way to this bulletin. -

Non-Wood Forest Products

Non-farm income wo from non- od forest prod ucts FAO Diversification booklet 12 FAO Diversification Diversification booklet number 12 Non-farm income wo from non- od forest products Elaine Marshall and Cherukat Chandrasekharan Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders.