Non-Wood Forest Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Bulletin 147

Q 11 U563 CRLSSI BULLETIN 147 MAP U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM 's SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Bulletin 147 ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN SAMANA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC BY HERBERT W. KRIEGER Curator of Ethnology, United States National Museum UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1929 For sale by ths Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 40 Cents ADVERTISEMENT The scientific publications of the National Museum include two series, known, respectively, as Proceedings and Bulletin. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, is intended primarily as a medium for the publication of original papers, based on the collections of the National Museum, that set forth newly acquired facts in biology, anthropology, and geology, with descriptions of new forms and revisions of limited groups. Copies of each paper, in pamphlet form, are distributed as published to libraries and scientific organ- izations and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects. The dates at which these separate papers are published are recorded in the table of contents of each of the volumes. The Bulletin, the first of which was issued in 1875, consist of a series of separate publications comprising monographs of large zoological groups and other general systematic treatises (occasion- ally in several volumes), faunal works, reports of expeditions, cata- logues of type-specimens, special collections, and other material of similar nature. The majority of the volumes are octavo in size, but a quarto size has been adopted in a few instances in which large plates were regarded as indispensable. In the Bulletin series appear volumes under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herharium, in octavo form, published by the National Museum since 1902, which contain papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum. -

The Miracle Resource Eco-Link

Since 1989 Eco-Link Linking Social, Economic, and Ecological Issues The Miracle Resource Volume 14, Number 1 In the children’s book “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein the main character is shown to beneÞ t in several ways from the generosity of one tree. The tree is a source of recreation, commodities, and solace. In this parable of giving, one is impressed by the wealth that a simple tree has to offer people: shade, food, lumber, comfort. And if we look beyond the wealth of a single tree to the benefits that we derive from entire forests one cannot help but be impressed by the bounty unmatched by any other natural resource in the world. That’s why trees are called the miracle resource. The forest is a factory where trees manufacture wood using energy from the sun, water and nutrients from the soil, and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In healthy growing forests, trees produce pure oxygen for us to breathe. Forests also provide clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities to renew our spirits. Forests, trees, and wood have always been essential to civilization. In ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq), the value of wood was equal to that of precious gems, stones, and metals. In Mycenaean Greece, wood was used to feed the great bronze furnaces that forged Greek culture. Rome’s monetary system was based on silver which required huge quantities of wood to convert ore into metal. For thousands of years, wood has been used for weapons and ships of war. Nations rose and fell based on their use and misuse of the forest resource. -

International Poplar Commission Poplars, Willows and People's Wellbeing

INTERNATIONAL POPLAR COMMISSION 23rd Session Beijing, China, 27 – 30 October 2008 POPLARS, WILLOWS AND PEOPLE’S WELLBEING Synthesis of Country Progress Reports Activities Related to Poplar and Willow Cultivation and Utilization, 2004 through 2007 October 2008 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper IPC/6E Forest Management Division FAO, Rome, Italy Forestry Department Disclaimer Nineteen member countries of the IPC have provided national progress reports to the 23rd Session of the International Poplar Commission. A Synthesis has been made by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and summarizes issues, highlights status and identifies trends affecting cultivation, management and utilization of Poplars and Willows in temperate and boreal regions of the world. Comments and feedback are welcome. For further information, please contact: Mr. Jim Carle Secretary International Poplar Commission Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Viale delle Terme di Caracalla I-00153 Rome ITALY E-mail: [email protected] For quotation: FAO, October 2008. Synthesis of Country Progress Reports received, prepared for the 23rd Session of the International Poplar Commission, jointly hosted by FAO and by the Beijing Forestry University, the State Forest Administration of China and the Chinese Academy of Forestry; Beijing, China, 27-30 October 2008. International Poplar Commission, Working, Paper IPC/6. Forest Management Division, FAO, Rome (unpublished). Web references: For details relating to the International Poplar Commission as a Technical Statutory Body of FAO, including National Poplar Commissions, working parties and initiatives, can be viewed on www.fao.org/forestry/ipc, and highlights of the 23rd Session of the International Poplar Commission 2008 can be viewed on www.fao.org/forestry/ipc2008. -

LATEX for Beginners

LATEX for Beginners Workbook Edition 5, March 2014 Document Reference: 3722-2014 Preface This is an absolute beginners guide to writing documents in LATEX using TeXworks. It assumes no prior knowledge of LATEX, or any other computing language. This workbook is designed to be used at the `LATEX for Beginners' student iSkills seminar, and also for self-paced study. Its aim is to introduce an absolute beginner to LATEX and teach the basic commands, so that they can create a simple document and find out whether LATEX will be useful to them. If you require this document in an alternative format, such as large print, please email [email protected]. Copyright c IS 2014 Permission is granted to any individual or institution to use, copy or redis- tribute this document whole or in part, so long as it is not sold for profit and provided that the above copyright notice and this permission notice appear in all copies. Where any part of this document is included in another document, due ac- knowledgement is required. i ii Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is LATEX?..........................1 1.2 Before You Start . .2 2 Document Structure 3 2.1 Essentials . .3 2.2 Troubleshooting . .5 2.3 Creating a Title . .5 2.4 Sections . .6 2.5 Labelling . .7 2.6 Table of Contents . .8 3 Typesetting Text 11 3.1 Font Effects . 11 3.2 Coloured Text . 11 3.3 Font Sizes . 12 3.4 Lists . 13 3.5 Comments & Spacing . 14 3.6 Special Characters . 15 4 Tables 17 4.1 Practical . -

Pdf, 11.42 Mb

FOTO: SAMUEL PORTELA INSTITUTIONS PARTICIPATING IN THE OVERALL COORDINATION VALIDATION WORKSHOP TECHNICAL TEAM AD2M CAATINGA ASSOCIATION ADECE Daniel Fernandes ASSOCIAÇÃO CAATINGA Kelly Cristina Luana Ribeiro CAPOL Lucas Moura CARNAÚBA DO BRASIL Marília Nascimento CEROEPER Sandino Silva COETRAE Samuel Portela EMBRAPA SDA FAEC Marcílio Melo FETRAECE FIEC EMBRAPA Vicente de Paula Queiroga FONCEPI GIZ FAEC HARIBO Ivonisa Holanda INSS Ossian Dias Jucileide Nogueira MEMORIAL DA CARNAÚBA MAPA GIZ MMA Octávio Nogueira MPT-CE Louisa Lösing MPT-PI INSS MPT-RN Ruiter Lima NATURA Irisa Viana NATURAL WAX Rafael Ferreira NRSC NUTEC PONTES INDÚSTRIA DE CERA Alessandra Nascimento Souza de Oliveira RODOLFO G. MORAES - ROGUIMO Iêda Nadja Silva Montenegro SDA SEJUS MMA Daniel Barbosa SINDCARNAÚBA SRTE-CE UEBT SRTE-RN Ronaldo Freitas STDS Rodrigo de Próspero UEBT ESPECIALISTAS CONVIDADOS UECE Carolina Serra INVITED EXPERTS Jessika Sampaio GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT Luana Ribeiro e Kelly Cristina FOTO: RENATO STOCKLER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This handbook was developed through a partnership between the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply (MAPA), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Associação Caatinga, within the framework of the Private Sector Action for Biodiversity Project, as part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI). The German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) supports this initiative based on a decision taken by the Bundestag. Acronyms ABNT - Brazilian -

SURINAME: COUNTRY REPORT to the FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE on PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig,1996)

S U R I N A M E c o u n t r y r e p o r t 1 SURINAME: COUNTRY REPORT TO THE FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE ON PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig,1996) Prepared by: Ministry of Agriculture Animal Husbandry and Fisheries Paramaribo, May 31 1995 S U R I N A M E c o u n t r y r e p o r t 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the FAO International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources, Leipzig, Germany, 17-23 June 1996. The Report is being made available by FAO as requested by the International Technical Conference. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of the material and maps in this document do not imply the expression of any option whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. S U R I N A M E c o u n t r y r e p o r t 3 Table of contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCION TO SURINAME AND ITS AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 5 1.1 GEOGRAPHY AND POPULATION 5 1.2 CLIMATE AND GEOMORPHOLOGICAL LAND-DIVISION 6 1.2.1 Agriculture 7 CHAPTER 2 INDIGENOUS PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES 9 2.1 FORESTRY GENETIC RESOURCES 9 2.2 AGRICULTURAL PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES 10 2.2.1 Ananas -

Non-Timber Forest Products

Agrodok 39 Non-timber forest products the value of wild plants Tinde van Andel This publication is sponsored by: ICCO, SNV and Tropenbos International © Agromisa Foundation and CTA, Wageningen, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. First edition: 2006 Author: Tinde van Andel Illustrator: Bertha Valois V. Design: Eva Kok Translation: Ninette de Zylva (editing) Printed by: Digigrafi, Wageningen, the Netherlands ISBN Agromisa: 90-8573-027-9 ISBN CTA: 92-9081-327-X Foreword Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are wild plant and animal pro- ducts harvested from forests, such as wild fruits, vegetables, nuts, edi- ble roots, honey, palm leaves, medicinal plants, poisons and bush meat. Millions of people – especially those living in rural areas in de- veloping countries – collect these products daily, and many regard selling them as a means of earning a living. This Agrodok presents an overview of the major commercial wild plant products from Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific. It explains their significance in traditional health care, social and ritual values, and forest conservation. It is designed to serve as a useful source of basic information for local forest dependent communities, especially those who harvest, process and market these products. We also hope that this Agrodok will help arouse the awareness of the potential of NTFPs among development organisations, local NGOs, government officials at local and regional level, and extension workers assisting local communities. Case studies from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Central and South Africa, the Pacific, Colombia and Suriname have been used to help illustrate the various important aspects of commercial NTFP harvesting. -

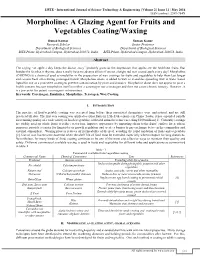

Morpholine: a Glazing Agent for Fruits and Vegetables Coating/Waxing (IJSTE/ Volume 2 / Issue 11 / 119) with Glazing Agent

IJSTE - International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering | Volume 2 | Issue 11 | May 2016 ISSN (online): 2349-784X Morpholine: A Glazing Agent for Fruits and Vegetables Coating/Waxing Rupak Kumar Suman Kapur Research Scholar Senior Professor Department of Biological Sciences Department of Biological Sciences BITS-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, Hyderabad-500078, India BITS-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, Hyderabad-500078, India Abstract The saying “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” probably gives us the impression that apples are the healthiest fruits. But besides the fact that it rhymes, does it really have no adverse effects if we eat a bright red wax coated apple every day? Morpholine (C4H9NO) is a chemical used as emulsifier in the preparation of wax coatings for fruits and vegetables to help them last longer and remain fresh even during prolonged transit. Morpholine oleate is added to wax as it enables spreading wax in water based liquid for use as a protective coating to prevent contamination by pests and diseases. Morpholine alone does not appear to pose a health concern because morpholine itself is neither a carcinogen nor a teratogen and does not cause chronic toxicity. However, it is a precursor for potent carcinogenic nitrosamines. Keywords: Carcinogen, Emulsifier, Morpholine, Teratogen, Wax Coating ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION The practice of fruit/vegetable coating was accepted long before their associated chemistries were understood, and are still practiced till date. The first wax coating was applied to citrus fruits in 12th-13th centuries in China. Today, it has expanded rapidly for retaining quality of a wide variety of foods/vegetables, with total annual revenue exceeding $100 million [1]. -

Rheological Properties of Asphalt Binders Modified with Natural Fibers and Oxidants

Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology (JMEST) ISSN: 2458-9403 Vol. 4 Issue 10, October - 2017 Rheological Properties of Asphalt Binders Modified With Natural Fibers and Oxidants T. M. F. Cunha G. Cardoso C. A. Frota Petrobras – REMAN Federal University of Sergipe Federal University of Amazonas Manaus - AM, Brazil Aracaju - SE, Brazil Manaus - AM, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The thermal and rheological A. Objective and Scope behaviors of asphalt binder modified with natural The aim of the present work is to improve the fibers and antioxidants obtained from the Amazon rheological characteristics (complex modulus, phase rain forest are analyzed through angle and viscosity) of the asphalt binder AC 50/70, Thermogravimetry (TG), Differential Scanning modifying it with raw materials from the Ama-zon Calorimetry (DSC) and Dynamical Shear biodiversity, with the perspective of sustainable use of Rheometer (DSR) tests. The addition of modifiers natural resources. The mechanical properties of AC alters considerably the physical and rheological 50/70 modified with those materials were compared properties of the modified binders. The main with those of pure AC 50/70 and that modified with results are: a good thermal stability and styrene-butadiene-styrene (SBS) copolymer. miscibility with asphalt cement (AC), significant increase of G* at low frequencies, decrease of As one of the natural modifier material we used and increase of the viscosity. The results are natural fiber obtained from the shell of a fruit compared with that of asphalt binder modified popularly known as Cutia-Chesnut (Couepia Edulis - with SBS polymer. -

A Contemporary Assessment of Tree Species in Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, Southern India

Proceedings of the International Academy of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2017, 7(2): 30-46 Article A contemporary assessment of tree species in Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, Southern India M. Sathya, S. Jayakumar Environmental Informatics and Spatial Modeling Lab, Department of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, School of Life Sciences, Pondicherry University, Puducherry 605014, India E-mail: [email protected] Received 28 December 2016; Accepted 5 February 2017; Published online 1 June 2017 Abstract Tree species inventory was carried out in five forest types of Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve (STR). The forest type was divided into homogenous vegetation strata (HVS) based on the altitude, temperature, precipitation and forest types. A total of 8 ha area was sampled using 0.1 ha (20m 50m) plot and all tree species ≥ 1cm girth at breast height (gbh) within the plot were enumerated. In all, 4614 individuals were recorded that belonged to 122 species representing 90 genera and 39 families. Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Rubiaceae, and Combretaceae were the species-rich families. The mean stand density of STR was 577 ha-1, but it varied from 180 ha-1 to 779 ha-1. Similarly, the mean basal area of the STR was 14.51 m2ha-1 which ranged between 8.41 m2 ha-1 and 26.96 m2 ha-1. The stem count was low at the lowest girth class (1-10 cm gbh) and high at 20-30 cm gbh in all the forest types. Anogeissus latifolia was the dominant species in the semi- evergreen and deciduous forest types while Chloroxylon swietenia was dominant in the thorn forest. -

+Woven Furnishings Inspired Children's Rooms

connecticut cottages connecticut cottages & gardens april 2021 | COTTAGESGARDENS.COM APRIL 2021 cottagesgardens.com WOVEN FURNISHINGS FRESH TAKE INSPIRED CHILDREN’S ON DESIGN +ROOMS WHAT’S NEW Out of the Box WRAPPED AND WOVEN—ORGANIC FURNISHINGS IN WICKER, RAFFIA, RATTAN AND ROPE | PRODUCED BY MARY FITZGERALD HANGING AROUND Inside or out, the Marina hanging chair from Arhaus invites fun and relaxation. Constructed in a powder- coated aluminum, the frame is wrapped in an all-weather rope. $2,349, SoNo Collection, Norwalk, arhaus.com. SUNNY OUTLOOK The ornate flower motif of Made Good’s Waverly mirror is formed from woven natural rattan wicker. $1,350, available through Housewarmings, Greenwich, madegoods.com. SIDE BAR The Balabac rattan sideboard from British style brand Oka is fashioned from mindi and durian wood. Rattan-wrapped doors are accented with metal ring handles. $1,650, oka.com. april 2021 cottagesgardens.com ctc&g 27 WHAT’S NEW WHAT’S NEW ROARING ’20S This rattan single CRISSCROSS PATTERN drawer bedside table The macramé effect of the Bandelier hails from Soane’s accent chair from Longaberger is Templeton collection achieved with interlaced white cowhide and was inspired by leather. The Danish- a 1920s design. The inspired design is SCREEN TIME elegant curved sides of finely crafted with Made in France, pale oak are wrapped sungkai wood in a the Scale screen in rattan. $5,125, natural finish. $459, from Atelier Vime is soane.com. longaberger.com. woven in rattan with A NEW TWIST wood and leather. Finely twisted jute is stretched over the metal frame of The French word the Manhattan pendant light from Selamat. -

Essential Oil Production Under Public Sector, Private Partnershipmodel

ESSENTIAL OIL PRODUCTION UNDER PUBLIC SECTOR, PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPMODEL - V.S. VENKATESHA GOWDA FORMER GENERAL MANAGER KARNATAKA SOAPS & DETERGENTS LTD., BANGALORE-55 1 INTRODUCTION: Definition of Essential Oil : The scented oil obtained from natural sources is called Essential oil. An essential oil may be defined as a volatile perfumery material derived from a single source of vegetable or animal origin, which has been separated from that source by a physical process. Natural Essential Oils Are The JEWELS OF NATURE – only Kings & Queens and rich persons were supposed to use these essential oils and barter with other valuables. 2 PRODUCTION OF ESSENTIAL OILS: India is already world leader as far as production and export of essential oils and their value added products are concerned. Many factors go in favour of our country, 1) Biodiversity 2) Scientific manpower 3) Processing industry 4) Huge investment in trade Unless, all these four parameters are well addressed by any country, an industry cannot grow and achieve distinction. 3 The production of essential oils can be grouped in to five categories, 1) Essential oils for processing 2) Essential oils for fragrances 3) Essential oils for flavours 4) Essential oils for aromatherapy and natural medicines 5) Essential oils for pharma oils. 4 WORLD PRODUCTION OF ESSENTIAL OILS FOR PROCESSING (2011) Essential Oil Quantity (in MTonnes) Producing Countries Basil 500 India Cederwood 3000 China, USA, India Citrodora 1000 China, Brazil, India, S.Africa Citronella 1500 China, Indonesia, India Clove Leaf 4000 Madagascar, Indonesia, Zanzibar Eucalyptus 5000 China, India, Australia Lemongrass 400 India, China, Guatemala Litsea cubeba 1500 China M.