(Instead Of) Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ljubljana Tourism

AKEYTOLJUBLJANA MANUAL FOR TRAVEL TRADE PROFESSIONALS Index Ljubljana 01 LJUBLJANA 02 FACTS 03 THE CITY Why Ljubljana ............................................................. 4 Numbers & figures.............................................. 10 Ljubljana’s history ................................................ 14 Ljubljana Tourism ................................................... 6 Getting to Ljubljana ........................................... 12 Plečnik’s Ljubljana ............................................... 16 Testimonials .................................................................. 8 Top City sights ......................................................... 18 City map ........................................................................... 9 ART & RELAX & 04 CULTURE 05 GREEN 06 ENJOY Art & culture .............................................................. 22 Green Ljubljana ...................................................... 28 Food & drink .............................................................. 36 Recreation & wellness .................................... 32 Shopping ...................................................................... 40 Souvenirs ..................................................................... 44 Entertainment ........................................................ 46 TOURS & 07 EXCURSIONS 08 ACCOMMODATION 09 INFO City tours & excursions ................................ 50 Hotels in Ljubljana .............................................. 58 Useful information ............................................ -

Fiction & Documentary

FICTION & DOCUMENTARY FICTION 2 Nightlife by Damjan Kozole 4 Mother by Vlado Škafar 6 Huston, We Have A Problem by Žiga Virc 8 Perseverance by Miha Knific 10 Nika by Slobodan Maksimović 12 A Comedy of Tears by Marko Sosič 14 Case: Osterberg by Matej Nahtigal 1 FICTION 16 Šiška Deluxe by Jan Cvitkovič IN 18 Idyll by Tomaž Gorkič FICTION PRODUCTION 32 20 Family Film by Olmo Omerzu 43 DOCUMENTARY 22 The High Sun by Dalibor Matanić IN 24 Life is a Trumpet by Antonio Nuić DOCUMENTARY PRODUCTION 58 26 Ministry of Love by Pavo Marinković 28 Lucy in the Sky by Giuseppe Petitto 30 Our Everyday Life by Ines Tanović Production: Slovenian Film Centre Editor: Inge Pangos Translation: Borut Praper Visual & design: Boštjan Lisec Print: Collegium Graphicum Print run: 700 Ljubljana, January 2016 Slovenian Film Guide_Fiction & Documentary 3 Nightlife by Damjan Kozole Nočno življenje, 2016, DCP, 1:2.35, in colour, 93 min Late at night, a renowned lawyer is found on the sidewalk of a busy street in Ljubljana. He is semi-conscious and his body is covered in blood from numerous dog bite wounds. Phy- sicians at the Ljubljana Medical Centre are fighting for his life, while his wife is coping with the shock and her deepest fears. During that night she breaks all of the moral princi- ples she has advocated all her life. Damjan Kozole (1964) is an award-winning filmmaker whose directing credits include the critically acclaimed Spare Parts, nominated for the Golden Bear at the 53th Berlin IFF, Selected Filmography and Slovenian Girl, which premiered in 2009 at Toronto, Pusan and Sarajevo IFF and has (feature) been distributed worldwide. -

Ebrochure (PDF)

Andreja Kopač, Ida Hiršenfelder EXERCISES IN NEXUS Andreja Kopač Constructions of Internal Spaces According to Neven Korda “When you have nowhere to go, when you no longer care, you will come to us, for we are leaders without adherents.” Neven Korda Defining the language of visual artist Neven Korda is a curious task, for it seems as if his anchorage points were located in some kind of vector space, in which a sought-after relation could be put into different perspectives between the vector plane and the scalar product. Since these are two complementary planes, we can assume that one dimension is represented by low-resolution visual language with it peculiar perceptual effects, while the other dimension is determined by discursive space of special enunciability, whose basic unit is formed as the minimal function of meaning. The discursive plane that is conceived in such a way is established anew every time, according to the individual internal logic of the event, which is part of current social events as well as part of the individual state of the author’s consciousness. Every event (show/performance/installation) by Neven Korda thus acquires the status of a special plane of enunciation, which on the one hand “consolidates” the discourse of one, while on the other hand it establishes a different kind of gaze every time, and through this gaze it addresses the viewer and itself. The smaller this unit, the more immediate communication with the viewer becomes. The latter often includes various technical flaws and performative privatisms, which gradually become part of the visual spectrum of low resolution, which – precisely by means of its conscious errors – resists intended representation, unambiguous interpretation or polished form in every possible way. -

Ljubljana August - September 2014

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Ljubljana August - September 2014 Emona Ljubljana’s 2000th birthday promises to be quite the celebration Ptuj Find out more about the oldest town in all of inyourpocket.com Slovenia Issue Nº37 FREE COPY city of opp ortunities In the last twenty years BtC CIty trademark has found Its plaCe under the slovene marketIng sky. today BtC CIty Is not only the BIggest shoppIng Centre, as It has also BeCome an Important BusIness Centre and a CIty wIth sports and Cultural events as well as a plaCe where CreatIve and BusIness Ideas Come to lIfe. therefore the BtC CIty trademark wIll also In the future foCus on CreatIng opportunItIes for a qualIty way of lIfe, InnovatIve Ideas and new vIsIons. www.btc-city.com BTC 2014 Oglas Corpo 143x210+5 In Your Pocket.indd 1 7/22/14 11:19 AM Argentino / Šmartinska 152 (BTC) / 1000 Ljubljana / Slovenija Typical style of an Argentinian hacienda. Always fresh meat, best quality beef from Argentina. Indulge yourself with our grilled specialities. Old Argentinian recipes, on typical grills imported from Argentina. Wine Cellar with over 130 Argentinian Wines www.argentino.si / mobile: +386 31 600 900 InYourPocket 143x210 0313.indd 1 20.3.13 9:31 Contents ESSENTIAL CIT Y GUIDES Arrival & Transport 8 Planes, trains, buses, taxis and transfers Emona 13 Happy 2000th birthday Ljubljana! Culture & Events 15 Festivals, exhibitions, music and much more Restaurants 25 Everything from A to V(egetarian) Cafés 42 Enjoy one of Ljubljana’s favourite pastimes Nightlife -

Ljubljana, Slovenia Spring Semester 2016

Travel Report Ljubljana, Slovenia Spring Semester 2016 462305 University of Ljubljana Faculty of Economics 1 1. Preparing for the exchange Slovenia is a EU-country, the requirements for EU-citizens are not too extensive. Personal top-tip: Unless you are living in the dorms (where it is a requirement), skip the residence permit. Nobody will ever ask you for it and at least for me it was quite an inconvenience to get it. I went to the agency and filled all the papers with a clerk there, however, all of it was wrong. First, I had to come again, because the form I filled (which was handed to me by the lady there) was the wrong one. Later, I had to hand in a copy of my e-card again; I only copied one side, but both sides would have been necessary. Finally, when my application was processed, they lost my residence permit card. After a week or so, they informed me that they found it in another guy’s application folder. The whole endeavour took from the beginning of February until the beginning of April and I have been to the agency about 5 times – there is always a long waiting line. Nobody ever asked me about the permit and most EU-students just never applied for one. There are multiple ways to travel from Helsinki to Ljubljana. There are no direct flights, but you can change at any bigger German Airport or in Stockholm. The flights to LJU can be quite expensive, consider also going to close Airports like Trieste, Venice, Klagenfurt (e.g. -

Dobra Slovenia! Newsletter: 21 February 2020

Newsletter 21 February 2020 DOBRA SLOVENIA! All about the art scene Edited by Monique du Plessis Featured in 2019 as part LJUBLJANA’S UNDERGROUND ART of the 33rd Biennale of SCENE the Graphic Arts in This edition will cover all things art in Slovenia. From its 33rd Graphic Arts Biennale which took place last year to its under-the-radar art scene spurred on by independent galleries and the MSUM (Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova), this issue will give you the inside scoop on this exciting up- and-coming art hub. Newsletter !1 Newsletter 21 February 2020 FRIEZE MAGAZINE: 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts and The Powerful Language of Satire By Emily Mcdermott For ‘Crack Up – Crack Down’, the 33rd Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, the collective Slavs and Tatars took satire as a thematic starting point. ‘How does graphic language, designed for clarity,’ they ask in the show’s curatorial statement, ‘allow for the ambiguity crucial for art’s affective potential as well as its infra-political resistance?’ This question is explored through the presentation of more than 100 works by 30 artists spread across nine venues in the Slovenian capital. Slavs and Tatars’ approach aligns with the original impetus of the biennial, which, from its inception in 1955, sought to use the low cost of production and portability of graphic arts to enable Nicole Wermers, Double Sand dialogue between artists on both sides of Table, 2007-18, installation view, 33rd Ljubljana Biennial, 2019 the Iron Curtain. In 1963, for example, work by Robert Rauschenberg was able to hang alongside that of Russian artist Erik Bulatov because the artists could have, theoretically, put prints in tubes and dropped them in the mail. -

Volišča Dostopna Invalidomslovenski

VE OVK SEDEŽ OVK SEDEŽ VOLIŠČA glasovalna naprava 1 1 JESENICE KRANJSKA GORA 1, OBČINA KR.GORA, KOLODVORSKA UL.1 B 1 1 JESENICE KRANJSKA GORA 2, OŠ KRANJSKA GORA, KOROŠKA ULICA 12 1 1 JESENICE KRANJSKA GORA 3, OŠ KRANJSKA GORA, KOROŠKA ULICA 12 1 1 JESENICE BELCA, HIŠA HLEBANJA, BELCA 15 1 1 JESENICE MOJSTRANA 1, OŠ 16.DECEMBER, ULICA ALOJZA RABIČA 7 1 1 JESENICE MOJSTRANA 2, OŠ 16.DECEMBER, ULICA ALOJZA RABIČA 7 1 1 JESENICE ZG. RADOVNA, HIŠA TNP, ZG. RADOVNA 21 1 1 JESENICE HRUŠICA, KULTURNI DOM NA HRUŠICI, HRUŠICA 55 A 1 1 JESENICE PLANINA POD GOLICO, STAVBA ŽUPNJIŠČA, PLANINA POD GOLICO 55 1 1 JESENICE PLANINA POD GOLICO, STAVBA ŽUPNJIŠČA, PLANINA POD GOLICO 55 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 1, DOM UPOKOJENCEV DR. F. BERGLJA, PRITLIČJE STAVBE B 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 3, PRITLIČJE OŠ TONE ČUFAR, UČILNICA 1 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 4, KOSOVA GRAŠČINA - GALERIJA, CESTA MARŠALA TITA 64 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 5, JEKO-IN, CESTA MARŠALA TITA 51 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 6, PRITLIČJE OŠ TONE ČUFAR, UČILNICA 3 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 7, PRITLIČJE OŠ TONE ČUFAR, UČILNICA 2 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 8, VRTEC A. OCEPEK, 1. VHOD, CESTA CIRILA TAVČARJA 3A 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 9, ZPIZ, CESTA MARŠALA TITA 73 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 10, VRTEC A. OCEPEK, 1. VHOD, CESTA CIRILA TAVČARJA 3A 1 1 JESENICE PLAVŽ 11, VRTEC A. OCEPEK, 2. VHOD, CESTA CIRILA TAVČARJA 3A 1 1 JESENICE SAVA 2, KRAJEVNA SKUPNOST SAVA, POD GOZDOM 2 1 1 JESENICE SAVA 4, ČAVS BAR, CESTA TONETA TOMŠIČA 70 A 1 1 JESENICE PODMEŽAKLA 1, SEJNA SOBA ŠD, LEDARSKA ULICA 4 1 1 JESENICE PODMEŽAKLA 2, KRAJEVNA SKUPNOST, MENCINGERJEVA UL. -

LIGHTING GUERRILLA the CITY!, May 25Th - June 12Th 2010, Ljubljana, Kranj, Slovenia

LIGHTING GUERRILLA THE CITY!, May 25th - June 12th 2010, Ljubljana, Kranj, Slovenia www.svetlobnagverila.net City! is the motto with which we aim to add a new dimension to the urban public space, and a tint of interesting and exciting for its residents and visitors, using installations by international authors. Each individual installation and the entire project reminds us that the city is a living, transforming organism that should not be taken for granted; and that not everything is what it seems. The city (can) offer different levels of life quality and various possibilities of spending leisure time. Our temporary interventions wish to encourage you, both residents and visitors, to take a different look, be it on the city itself, with its public spaces, or on the artist's part in co-designing the city and the quality of life in it. City! includes the AKC Metelkova mesto, the central Bus station Ljubljana, the Parki-Raj parking garage on Trdinova Street, the Miklošičev park, Nazorjeva and Čopova streets, the Dragon Bridge, The Three Bridges, the Zlata ladjicapub on Breg embankment, the Cankarjev Dom platform, the Northern park in Župančičeva jama and Hrvatski trg square, in front of St Peter's church. City! will be opened by the interactive installation with the title Human Tiles by the Portuguese group Ocubo; the piece is supplemented by the lighting objects designed by Andrej Štular, Marko A. Kovačič and Brane Ždralo. Their designs are linked to the year of the book events that invite us to bold readings of poetry, comics, etc. Aleksandra Stratimirović, a Serbian artist from Sweden, plans to release the kind spirits right in the center of the city; architect Katja Lavriša will redesign the street lamps; Marjeta Zupančič will be creating an underwater city with the help from participants of her workshop; Natan will fire up imaginations with Proerectors, the atmospherical-recycled projectors. -

1 Katja Praznik Associate Professor 241A Center for the Arts University

Katja Praznik Associate Professor 241A Center for the Arts University at Buffalo, SUNY Buffalo, NY 14260 (email) [email protected] Buffalo, Sept 8, 2020 EMPLOYMENT 2020– Associate Professor, Arts Management Program/Department of Media Study, University at Buffalo 2013–2020 Assistant professor, Arts Management Program/Department of Media Study, University at Buffalo 2012–2013 Visiting assistant professor, Arts Management Program/Department of Media Study, University at Buffalo 2009–2012 Project manager and developer, Asociacija – Association of Arts and Culture NGOs and Freelancers, Ljubljana, Slovenia 2007–2009 Editor in chief, Maska – Performing Arts Journal, Ljubljana, Slovenia EDUCATION 2013 Ph.D. in Sociology, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Dissertation: Intellectual Domination: Contemporary Art Between the East and The West; advisor: Dr. Rastko Močnik 2006 M.A. Sociology of Culture, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia 2003 B.A. Comparative Literature and Literary Theory, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia BOOKS PUBLISHED Art Work: Invisible Labor and the Legacy of Yugoslav Socialism, University of Toronto Press, 2021 (in print) Paradoks neplačanega umetniškega dela: avtonomija umetnosti, avantgarda in kulturna politika na prehodu v postsocializem [The Paradox of Unpaid Artistic Labor: The Autonomy of Art, the Avant-Garde, and Cultural Policy in the Transition to Post-Socialism]. Ljubljana: Založba Sophia, 2016. Excerpts of two chapters reprinted in a Slovene newspaper supplement vSoboto, and an online portal for art and social issues Proletter Reviews and Interviews: 1. Kristina Božič, “Zakaj ne bi zahtevali, da država uredi delovne razmere? Intervju s Katjo Praznik [Why wouldn’t we demand that the state regulates the working conditions? An Interview with Katja Praznik]”, Večer – vSoboto, vol. -

Oveview of the Scene

ART IN A WEEK FACULTY OF ARTS/APRIL 2013 Welcome DEAR ARTISTS, this is a brief introduction to the program, which will be organized during your visit to Ljubljana in April 2013. We gathered descriptions of places you will be visiting, and the information on the curators that will be guiding us through a wide variety of different galleries. A map comes in handy, so we added that as well. We hope you enjoy your visit. Friday April 4 Saturday April 5 Sincerely MUSEUM OF MODERN ART AKSIOMA GALLERY 10.00 am – 11.3o am 11.00 am – 11.45 am INTERNATIONAL CENTRE OF GALLERY CHAPEL GRAPHIC ARTS 12.15 am – 1.00 pm 11.45 am – 1.15 pm lunch break lunch break P. NEMEC GALLERY CITY ART GALLERY 2.30 pm – 3.00 pm 2.30 pm – 4.00 pm MATCH GALLERY MUSEUM OF 3.30 pm – 4.00 pm CONTEMPORARY ART 4.15 pm – 6.00 pm ALKATRAZ GALLERY 4.15 pm – Publication designed by Adrijana Petrič TINA KRALJ TIM MAVRIČ ADRIJANA PETRIČ British inter-media artist Anthony Hall My favourite exhibition was the one of Miroslav Can’t wait to see the Retrospective brought about what most of us thought was Cukovic at the MGLC, he uses the technique of exhibition in Modern gallery once again - this possible only in dreams - communication with collage in quite an interesting way: he takes time with our guests and the guidence of emptiness and makes something out of it. a fish. (In the Gallery Kapelica.) curator Marko Jenko. Museum of Modern Art, MG by Eva Malalan Beside the exhibitions MG also student established specialized library, • • • Documentation Department and ABOUT THE MG Information Centre that have The Museum of Modern Art/ become an important resource of Moderna galerija (MG) in Ljubljana information about Slovene modern is Slovene national museum of and contemporary art. -

The Key Factor for a Successful Territorial Cohesion: Cross-Border Cooperation –

European Journal of Geography Volume 11, Issue 2, pp. 123 - 136 Article Info: Received: 03/09/2020; Accepted: 12/12/2020 Corresponding Authors: * [email protected] https://doi.org/10.48088/ejg.p.kum.11.2.123.136 Hidden geographies of social justice in an urban environment: the particularities of naturally-occurring arts districts Peter KUMER1*, 1 Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, Slovenia Keywords: Abstract hidden geographies, Despite extensive research on the role arts districts play in the economic right to the city, development of cities, little is known about the dynamics of social interactions just city, within those districts and their impact on society. Drawing on 26 interviews with cultural quarters, actors and stakeholders of arts districts in Ljubljana, this paper explores the role creativity, of arts districts in creating a just city. Four dimensions of such districts, which urban geography represent the meaningful themes that emerged from the data, are examined. The first dimension is the interrelationship of artists, cultural workers and activists. The second dimension encompasses mutual support and forms of self-governance, whereas the third dimension investigates the role arts districts play in the neighbourhood. The fourth dimension seeks to define the role of arts districts as part of urban development generally driven by capital. The results show that arts districts are important in the struggle for the right to the city. Actors from these districts are committed to addressing the causes of social inequality at their root via artist-led civic engagement activities. The publication of the European Journal of Geography (EJG) is based on the European Association of Geographers’ goal to make European Geography a worldwide reference and standard. -

SKLEP O Sofinanciranju Strokovnih Vsebin Prireditev Na Podezelju

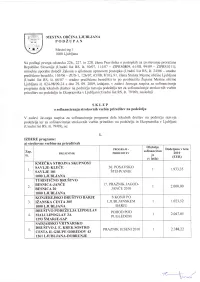

MESTNA OBCINA LJUBLJANA PODZUPAN Mestni trg I 1000 Ljubljana Na podlagi prvega odstavka 226.,227. in 228. dlena Pravilnika o postopkih za izvrievanje proraduna Republike Slovenije (Uradni list RS, 5t. 50/07, ll4107 - ZIPRS0809, 6ll08,99/09 - ZIPRSl0ll), smiselne uporabe dolodil Zakona o splo5nem upravnem postopku (Uradni list RS, 5t. 24106 - uradno predi5deno besedilo, 105/06 ZUS- l, 126107 , 65108, 8/10), 91 . dlena Statuta M-estne obdine Ljubljana (Uradni list RS, 5t. 66107 uradno prediSdeno besedilo) in po pooblastilu Zupana Mestne obdine Ljubljana #. 024-98109-24 z dne 29.09. 2009, izdajam, v zadevi Javnega razpisa za sofinanciranje programa dela lokalnih dru5tev na podrodju razvoja podeZelja ter za sofinanciranje strokovnih vsebin prireditev na podeZelju in Ekopraznika v Ljubljani (Uradni list RS, 5t. 79109), naslednji SKLEP o sofinanciranju strokovnih vsebin prireditev na podeZelju V zadevi Javnega razpisa za sofinanciranje programa dela lokalnih druStev na podrodju razvoja podeZelja ter za sofinanciranje strokovnih vsebin prireditev na podeZelju in Ekopraznika v Ljubljani (Uradni list RS, 5t. 79109), se: IZBERE programe: al strokovne vsebine na rireditvah Obdobje PROGRA}I - Dodeljeno Y letu zap. sofinanciran PRIJENINIK PRIRfDITEV ja 2010 5t. (EUR) (v letih) KMEEKA STROJNA SKUPNOST 56. POSAVSKO SAVLJE.KLEEE I I q1t t5 SAVLJf, 101 srgnvaNrE, rOOO LJUBLJANA TURISTICNO DRUSTVO BESNICA-JANCE 17. PRAZNIK JAGOD- 2. I 2.000,00 BESNICA 20 JANCE 20 I O 1OOO LJUBLJANA KONJf, REJSKO DRUSTVO BARJE S KONJI PO 3. IZANSKA CESTA 305 LJ UBLJANSKEM I 1 .023,52. IOOO LJUBLJANA BARJU nnuSTvO PONEZELJA LIPOGLAV POHOD POD ,1 1 2.041.05 MALILIPOGLAV34. PUGLEDOM 1293 SMARJE-SAP SADJARSKO VRTNARSKO DRUSTVO J.