Resecting Branchial Cysts, Fistulae and Sinuses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embryology of Branchial Region

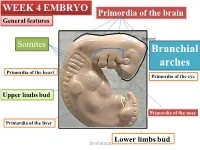

TRANSCRIPTIONS OF NARRATIONS FOR EMBRYOLOGY OF THE BRANCHIAL REGION Branchial Arch Development, slide 2 This is a very familiar picture - a median sagittal section of a four week embryo. I have actually done one thing correctly, I have eliminated the oropharyngeal membrane, which does disappear sometime during the fourth week of development. The cloacal membrane, as you know, doesn't disappear until the seventh week, and therefore it is still intact here, but unlabeled. But, I've labeled a couple of things not mentioned before. First of all, the most cranial part of the foregut, that is, the part that is cranial to the chest region, is called the pharynx. The part of the foregut in the chest region is called the esophagus; you probably knew that. And then, leading to the pharynx from the outside, is an ectodermal inpocketing, which is called the stomodeum. That originally led to the oropharyngeal membrane, but now that the oropharyngeal membrane is ruptured, the stomodeum is a pathway between the amniotic cavity and the lumen of the foregut. The stomodeum is going to become your oral cavity. Branchial Arch Development, slide 3 This is an actual picture of a four-week embryo. It's about 5mm crown-rump length. The stomodeum is labeled - that is the future oral cavity that leads to the pharynx through the ruptured oropharyngeal membrane. And I've also indicated these ridges separated by grooves that lie caudal to the stomodeum and cranial to the heart, which are called branchial arches. Now, if this is a four- week old embryo, clearly these things have developed during the fourth week, and I've never mentioned them before. -

Syndromes of the First and Second Branchial Arches, Part 1: Embryology and Characteristic REVIEW ARTICLE Defects

Syndromes of the First and Second Branchial Arches, Part 1: Embryology and Characteristic REVIEW ARTICLE Defects J.M. Johnson SUMMARY: A variety of congenital syndromes affecting the face occur due to defects involving the G. Moonis first and second BAs. Radiographic evaluation of craniofacial deformities is necessary to define aberrant anatomy, plan surgical procedures, and evaluate the effects of craniofacial growth and G.E. Green surgical reconstructions. High-resolution CT has proved vital in determining the nature and extent of R. Carmody these syndromes. The radiologic evaluation of syndromes of the first and second BAs should begin H.N. Burbank first by studying a series of isolated defects: CL with or without CP, micrognathia, and EAC atresia, which compose the major features of these syndromes and allow more specific diagnosis. After discussion of these defects and the associated embryology, we proceed to discuss the VCFS, PRS, ACS, TCS, Stickler syndrome, and HFM. ABBREVIATIONS: ACS ϭ auriculocondylar syndrome; BA ϭ branchial arch; CL ϭ cleft lip; CL/P ϭ cleft lip/palate; CP ϭ cleft palate; EAC ϭ external auditory canal; HFM ϭ hemifacial microsomia; MDCT ϭ multidetector CT; PRS ϭ Pierre Robin sequence; TCS ϭ Treacher Collins syndrome; VCFS ϭ velocardiofacial syndrome adiographic evaluation of craniofacial deformities is nec- major features of the syndromes of the first and second BAs. Ressary to define aberrant anatomy, plan surgical proce- Part 2 of this review discusses the syndromes and their radio- dures, and evaluate the effects of craniofacial growth and sur- graphic features: PRS, HFM, ACS, TCS, Stickler syndrome, gical reconstructions.1 The recent rapid proliferation of and VCFS. -

![The Pharyngeal Arches [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8257/the-pharyngeal-arches-pdf-1328257.webp)

The Pharyngeal Arches [PDF]

24.3.2015 The Pharyngeal Arches Dr. Archana Rani Associate Professor Department of Anatomy KGMU UP, Lucknow What is Pharyngeal Arch? • Rod-like thickenings of mesoderm present in the wall of the foregut. • They appear in 4th-5th weeks of development. • Contribute to the characteristic external appearance of the embryo. • As its development resembles with gills (branchia: Greek word) in fishes & amphibians, therefore also called as branchial arch. Formation of Pharyngeal Arches Lens N Pharyngeal Apparatus Pharyngeal apparatus consists of: • Pharyngeal arches • Pharyngeal pouches • Pharyngeal grooves/clefts • Pharyngeal membrane Pharyngeal Arches • Pharyngeal arches begin to develop early in the fourth week as neural crest cells migrate into the head and neck region. • The first pair of pharyngeal arches (primordium of jaws) appears as a surface elevations lateral to the developing pharynx. • Soon other arches appear as obliquely disposed, rounded ridges on each side of the future head and neck regions. Le N Pharyngeal Arches • By the end of the fourth week, four pairs of pharyngeal arches are visible externally. • The fifth and sixth arches are rudimentary and are not visible on the surface of the embryo. • The pharyngeal arches are separated from each other by fissures called pharyngeal grooves/clefts. • They are numbered in craniocaudal sequence. Pharyngeal Arch Components • Each pharyngeal arch consists of a core of mesenchyme. • Is covered externally by ectoderm and internally by endoderm. • In the third week, the original mesenchyme is derived from mesoderm. • During the fourth week, most of the mesenchyme is derived from neural crest cells that migrate into the pharyngeal arches. Structures in a Pharyngeal Arch Arrangement of nerves supplying the pharyngeal arch (in lower animals) Fate of Pharyngeal Arches A typical pharyngeal arch contains: • An aortic arch, an artery that arises from the truncus arteriosus of the primordial heart. -

Cervical Cysts and Fistulae

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1938 Cervical cysts and fistulae Frederick Dee Koehne University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Koehne, Frederick Dee, "Cervical cysts and fistulae" (1938). MD Theses. 673. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/673 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,;/'"- CERVICAL CYSTS AND F'ISTULAE FREDERICK DEE KOEHNE Senior Thesis Presented to the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, Omaha, 1938. / -- / OUTLINE I. Introduction. A. In~oductory statement B. Definition c. Classification 1. Lateral cysts and fistulae 2. Mid-line cysts and fistulae D. Purpose II. Hlsto191' III. Lateral or BM.. nchial Cysts and Fistulae. A. Embryology 1. Normal embryology of the branchial ap parat_us. 2. Cervical Sinus theory--Second branchial cleft. 3. Thymic duct theorr• 4. Any cleft and cervical sinus. B. Pathology C. · S}'Dlptoma , , diagnosis and di ff eren tial diagnosis. D. Treatment~ IV. Mid-line or Thyroglossal duct cysts and fistulae. A. Embryology 1. Normal 2. Theory -~s to origin. B. Pathology 480951 c. Symptoms, di"agnosis and differential diagnosis. D. Treatment. v • sUlllil18.17' • r 1. PAR'r I. Introduction. The subject of Cervical cysts and fistuae has, for the past century, been one for considerable speculation and controversy. -

LESSON 2 DEVELOPMENT of the PHARYNGEAL ARCHES & POUCHES Objectives by the End of This Lesson You Should Be Able To: 1

LESSON 2 DEVELOPMENT OF THE PHARYNGEAL ARCHES & POUCHES Objectives By the end of this lesson you should be able to: 1. Describe the development of pharyngeal arches 2. Describe the development of pharyngeal pouches 3. Describe the derivatives of pharyngeal arches and pouches 4. Describe the development of the tongue 5. Describe the development of the face 6. Describe the development of the thyroid gland 7. Describe the development of the nasal cavity DEVELOPMENT OF THE PHARYNGEAL APPARATUS In the 4th and 5th week of the development, the formation of the pharyngeal (branchial) arches in the head and neck region contributes greatly to the external appearance of the embryo. • The pharyngeal arches form as the masses of mesenchymal tissue which are invaded by the cranial neural crest cells. • Each pharyngeal arch is externally covered by the ectoderm and internally by the endoderm . • The pharyngeal arches are separated by deep ectodermal clefts called pharyngeal clefts (grooves) . • The endoderm of the pharynx, which lines the internal surface of pharyngeal arches, passes into evaginations called the pharyngeal pouches . Pharyngeal arches – 5th week 1. Pharyngeal arches 2. Lens placode 3. Pericardial swelling 4. Pharyngeal clefts 5. Hand bud Derivatives of pharyngeal pouches 1. External auditory meatus 2. Auditory tube 3. Primary tympanic cavity 4. Cervical sinus 5. Inferior parathyroid gland 6. Thymus 7. Palatine tonsil 8. Superior parathyroid gland 9. Ultimobranchial body pouches 1. Auditory tube 2. Foramen cecum 3. Palatine tonsil 4. Ventral side of pharynx 5. Tympanic cavity 6. Thyroid gland 7. Ultimobranchial body 8. Foregut 9. Thymus 10. Inferior parathyroid gland 11. -

Cleft Palate Are Common Defects That Result in Abnormal Facial Appearance and Defective Speech

WEEK 4 EMBRYO Primordia of the brain General features shatarat Somites Branchial arches Primordia of the heart Primordia of the eye Upper limbs bud Primordia of the nose Primordia of the liver Lower limbs bud Dr.shatarat The most important feature in the development of the head and neck is the Formation of THE PHARYNGEAL OR BRANCHIALARCHES shatarat Dr.shatarat Is it branchial or is it pharyngeal arch? development of pharyngeal arches resembles formation of gills in fish However, in the human embryo real gills (branchia) are never formed. Therefore, the term pharyngeal arches has been adopted for the human embryo Dr.shatarat shatarat THE PHARYNGEALARCHES appear in the fourth and fifth weeks of development Dr.shatarat Why the appear? Migration of cells from epiblast Dr.shatarat 1-PARAXIALMESODERM 2-LATERALPLATE MESODERM 3-NEURALCREST Dr.shatarat Migration of the cells from the occipital Myotomes into the future mouth to form the tongue Occipital somites This is an explanation to how the arches appear…. as a result of migration of the cells from the medial mesoderm (somites) into tongue the regions of the future head and neck. As we mentioned there are other reasons Dr.shatarat In a cross section of the embryo in the area of the head and neck The following can be noticed THE PHARYNGEALARCHES shatarat THE PHARYNGEALARCHES are separated by deep clefts known as PHARYNGEAL CLEFTS with development of the arches and clefts, a number of outpocketings, The pharyngeal pouches appear Dr.shatarat 1-PHARYNGEAL ARCHs Dr.shatarat 6 However, The fifth and sixth arches are rudimentary and are not visible on the surface of the embryo T h e y a re n u m b e r e d i n c r a n i o ca ud a During the fifth week, the second pharyngeal l s e arch enlarges and overgrows the third and qu fourth arches, forming the ectodermal e n c depression called cervical sinus e Dr.shatarat Each pharyngeal arch consists of: 1-surface ECTODERM 2-a core of MESENCHYMALtissue 3- epithelium of ENDODERMAL origin Each pharyngeal arch contains: 1- An artery that arises from the primordial heart A. -

Pharyngeal Arches. Pharyngeal Pouches

Multimedial Unit of Dept. of Anatomy Jagiellonian University The head and neck regions of a 4-week human embryo somewhat resemble these regions of a fish embryo of a comparable stage of development. This explains the former use of the designation „branchial apparatus” – the adjective „branchial” is derived from the Greek word branchia – the gill. The pharyngeal apparatus consists of: pharyngeal arches pharyngeal pouches pharyngeal grooves pharyngeal membranes The pharyngeal arches begin to develop early in the fourth week as neural crest cells migrate into the future head and neck regions. Drawings illustrating the human pharyngeal apparatus. The first pharyngeal arch (mandibular arch) develops two prominences the maxillary prominence (gives rise to maxilla, zygomatic bone, and squamous part of temporal bone) the mandibular prominence (forms the mandible) Drawings illustrating the human pharyngeal apparatus. Drawings illustrating the human pharyngeal apparatus. Drawings illustrating the human pharyngeal apparatus. Drawing of the head, neck, and thoracic regions of a human embryo (about 28 days), illustrating the pharyngeal apparatus. During the fifth week, the second pharyngeal arch enlarges and overgrows the third and fourth arches, forming an ectodermal depression – the cervical sinus. A - Lateral view of the head, neck, and thoracic regions of an embryo (about 32 days), showing the pharyngeal arches and cervical sinus. B - Diagrammatic section through the embryo at the level shown in A, illustrating growth of the second arch over -

Congenital Cervical Cysts, Sinuses and Fistulae Stephanie P

Otolaryngol Clin N Am 40 (2007) 161–176 Congenital Cervical Cysts, Sinuses and Fistulae Stephanie P. Acierno, MD, MPH, John H.T. Waldhausen, MD* Department of Surgery, Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, University of Washington School of Medicine, G0035, 4800 Sand Point Way, NE, Seattle, WA 98105, USA Congenital cervical cysts, sinuses, and fistulae must be considered in the diagnosis of head and neck masses in children and adults. These include, in descending order of frequency, thyroglossal duct cysts, branchial cleft anomalies, dermoid cysts, and median cervical clefts. A thorough understand- ing of the embryology and anatomy of each of these lesions is necessary to provide accurate preoperative diagnosis and appropriate surgical therapy, which are essential to prevent recurrence. The following sections review each lesion, its embryology, anatomy, common presentation, evaluation, and the key points in surgical management. Thyroglossal duct anomalies Thyroglossal duct anomalies are the second most common pediatric neck mass, behind adenopathy in frequency [1]. Thyroglossal duct remnants occur in approximately 7% of the population, although only a minority of these is ever symptomatic [1]. Embryology The thyroid gland forms from a diverticulum (median thyroid anlage) lo- cated between the anterior and posterior muscle complexes of the tongue at week 3 of gestation. As the embryo grows, the diverticulum is displaced cau- dally into the neck and fuses with components from the fourth and fifth * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] (J.H.T. Waldhausen). 0030-6665/07/$ - see front matter Ó 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2006.10.009 oto.theclinics.com 162 ACIERNO & WALDHAUSEN branchial pouches (lateral thyroid anlagen). -

26 April 2010 TE Prepublication Page 1 Nomina Generalia General Terms

26 April 2010 TE PrePublication Page 1 Nomina generalia General terms E1.0.0.0.0.0.1 Modus reproductionis Reproductive mode E1.0.0.0.0.0.2 Reproductio sexualis Sexual reproduction E1.0.0.0.0.0.3 Viviparitas Viviparity E1.0.0.0.0.0.4 Heterogamia Heterogamy E1.0.0.0.0.0.5 Endogamia Endogamy E1.0.0.0.0.0.6 Sequentia reproductionis Reproductive sequence E1.0.0.0.0.0.7 Ovulatio Ovulation E1.0.0.0.0.0.8 Erectio Erection E1.0.0.0.0.0.9 Coitus Coitus; Sexual intercourse E1.0.0.0.0.0.10 Ejaculatio1 Ejaculation E1.0.0.0.0.0.11 Emissio Emission E1.0.0.0.0.0.12 Ejaculatio vera Ejaculation proper E1.0.0.0.0.0.13 Semen Semen; Ejaculate E1.0.0.0.0.0.14 Inseminatio Insemination E1.0.0.0.0.0.15 Fertilisatio Fertilization E1.0.0.0.0.0.16 Fecundatio Fecundation; Impregnation E1.0.0.0.0.0.17 Superfecundatio Superfecundation E1.0.0.0.0.0.18 Superimpregnatio Superimpregnation E1.0.0.0.0.0.19 Superfetatio Superfetation E1.0.0.0.0.0.20 Ontogenesis Ontogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.21 Ontogenesis praenatalis Prenatal ontogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.22 Tempus praenatale; Tempus gestationis Prenatal period; Gestation period E1.0.0.0.0.0.23 Vita praenatalis Prenatal life E1.0.0.0.0.0.24 Vita intrauterina Intra-uterine life E1.0.0.0.0.0.25 Embryogenesis2 Embryogenesis; Embryogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.26 Fetogenesis3 Fetogenesis E1.0.0.0.0.0.27 Tempus natale Birth period E1.0.0.0.0.0.28 Ontogenesis postnatalis Postnatal ontogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.29 Vita postnatalis Postnatal life E1.0.1.0.0.0.1 Mensurae embryonicae et fetales4 Embryonic and fetal measurements E1.0.1.0.0.0.2 Aetas a fecundatione5 Fertilization -

Clinicopathological Characteristics of Cervical Chondrocutaneous Branchial Remnant: a Single-Institutional Experience

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10(9):9866-9877 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0059151 Original Article Clinicopathological characteristics of cervical chondrocutaneous branchial remnant: a single-institutional experience Ha Young Woo, Hyun-Soo Kim Department of Pathology, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea Received June 11, 2017; Accepted June 22, 2017; Epub September 1, 2017; Published September 15, 2017 Abstract: Cervical chondrocutaneous branchial remnant (CCBR) is an uncommon developmental anomaly typically seen on the lateral neck. We recently experienced four cases of CCBR and initiated a comprehensive review of previously published cases. During a 10-year period, four (0.4%) of the 1,096 patients who underwent excision of branchial cleft anomalies were diagnosed as having CCBR at our institution. Patient age ranged from 2-6 years and patients presented with asymptomatic cutaneous masses present since birth measuring approximately 1 cm on the lateral neck. Three patients had congenital thyroid hemiagenesis, subependymal cyst, and tongue tie, respectively. We identified 76 previously published cases of CCBR. The median age of these patients was 18 months. CCBR de- veloped more often in males (48/80; 60.0%). Most of the masses were located on the left (34/80; 42.5%) or right (18/80; 22.5%) lateral neck, whereas 23 (28.75%) involved bilateral lesions. Lesion size ranged from 0.3-3.5 cm. Grossly, the overlying skin of the masses was similar to the surrounding skin of the neck. Histologically, the lesions were covered by keratinizing squamous epithelium and had skin appendages and cartilage. -

Pharyngeal Pouches

Pharyngeal Arches Revisited and the 10. PHARYNGEAL POUCHES Letty Moss-Salentijn DDS, PhD Dr. Edwin S.Robinson Professor of Dentistry (in Anatomy and Cell Biology) E-mail: [email protected] READING ASSIGNMENT: Larsen 3rd edition: p.352; pp. 371-378; pp. 393 bottom-398 SUMMARY: The transient structures that are known as pharyngeal grooves and pharyngeal pouches disappear toward the end of the embryonic period. The first pharyngeal groove will give rise to the external auditory meatus of the adult ear. The other three grooves will disappear without having any further role in the development of adult structures. The pharyngeal pouches develop into a series of structures that include the pharyngotympanic tube, middle ear cavity, palatine tonsil, thymus, the four parathyroid glands, and the ultimobranchial bodies of the thyroid gland. The related development of the external ear by contributions of the first and second pharyngeal arches is reviewed, as is the development of the tongue, which is formed by contributions from the first through fourth arches. Finally, the development of the thyroid gland, which is spatially related to the derivatives of the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches, is discussed briefly. LEARNING OBJECTIVES You should be able to: a. List the derivatives of the first pharyngeal groove and describe the pattern of obliteration of pharyngeal grooves 2-4. b. List the derivatives of the different pharyngeal pouches. c. Describe briefly the development of the external and middle ear. d. List the different swellings and explain the process of merging of these swellings in the development of external ear and tongue. You should be able to list the pharyngeal arches that contribute to these swellings. -

Cervico-Auricular Fistulae a Review of Published Cases with a Report

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.40.210.218 on 1 April 1965. Downloaded from Arch. Dis. Childh., 1965, 40, 218. CERVICO-AURICULAR FISTULAE A REVIEW OF PUBLISHED CASES WITH A REPORT BY J. C. R. LINCOLN* From the Department ofSurgery, Hammersmith Hospital, Postgraduate Medical School ofLondon (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION JUNE 4, 1964) Congenital anomalies of the first branchial cleft or arches with four intervening clefts, the internal are rare. Approximately 32 cases of cervico- clefts being lined by foregut endoderm and the auricular fistulae have been reported in the past external clefts by ectoderm, but divided by a thin hundred years: this includes the writer's own case in layer of mesoderm. Though there is confusion in this review. The majority of sinuses and fistulae the nomenclature, the general consensus of opinion derived from the lateral cervical vestiges are con- names the pharyngeal clefts pharyngeal pouches, and cerned with the second pharyngeal pouch and its the corresponding external clefts branchial clefts. corresponding cleft. Each arch has a central core of cartilage, a main Auricular and pre-auricular fistulae are not blood vessel, and nerve. excessively rare, but cervico-auricular fistulae are still infrequently recorded. In some cases reported MAXILLARt >=j as cervico-auricular fistulae, there is little doubt from PROCESS the description that these are auricular or pre- Ist ARCH CARTILAGE copyright. 1st PHARYNGEAL ARCH auricular fistulae. - MAN1IRULAN NERVE Harding (1890) and Konig (1896) both recorded - 7th NERVE cases, but it was not until 1908 that Flint published a 2nd PHARYNGEAL ARCH , AYI well-documented case report on this condition.