The Hero of Karol Szymanowski's Opera King Roger In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2009

SUMMER 2009 • . BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR DALECHIHULY HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE 3 Elm Street, Stockbridge 413 -298-3044 www.holstengaIleries.com Olive Brown and Coral Pink Persian Set * for a Changing World They're Preparing to Change the 'I'Mi P i MISS HALL'S SCHOOL what girls have in mind 492 Holmes Road, Pittsfield, Massachusetts 01201 (413)499-1300 www.misshalls.org • e-mail: [email protected] m Final Weeks! TITIAN, TINTORETTO, VERONESE RIVALS IN RENAISSANCE VENICE " "Hot is the WOrdfor this show. —The New York Times Museum of Fine Arts, Boston March 15-August 16, 2009 Tickets: 800-440-6975 or www.mfa.ore BOSTON The exhibition is organized the Museum by The exhibition is PIONEER of Fine Arts, Boston and the Musee du sponsored £UniCredit Group by Investments* Louvre, and is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and Titian, Venus with a Mirror (detail), about 1555. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew the Humanities. W. Mellon Collection 1 937.1 .34. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 128th season, 2008-2009 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edward H. Linde, Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O'Block, Vice-Chairman Stephen Kay, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Edmund Kelly, Vice-Chairman • Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer • George D. Behrakis • Mark G. Borden • Alan Bressler • Jan Brett • Samuel B. Bruskin • Paul Buttenwieser • Eric D. -

557981 Bk Szymanowski EU

570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 16 Karol Also available: SZYMANOWSKI Harnasie (Ballet-Pantomime) Mandragora • Prince Potemkin, Incidental Music to Act V Ochman • Pinderak • Marciniec Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir • Antoni Wit 8.557981 8.570721 8.570723 16 570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 2 Karol SZYMANOWSKI Also available: (1882-1937) Harnasie, Op. 55 35:47 Text: Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) and Jerzy Mieczysław Rytard (1899-1970) Obraz I: Na hali (Tableau I: In the mountain pasture) 1 No. 1: Redyk (Driving the sheep) 5:09 2 No. 2: Scena mimiczna (zaloty) (Mimed Scene (Courtship)) 2:15 3 No. 3: Marsz zbójnicki (The Tatra Robbers’ March)* 1:43 4 No. 4: Scena mimiczna (Harna i Dziewczyna) (Mimed Scene (The Harna and the Girl))† 3:43 5 No. 5: Taniec zbójnicki – Finał (The Tatra Robbers’ Dance – Finale)† 4:42 Obraz II: W karczmie (Tableau II: In the inn) 6 No. 6a: Wesele (The Wedding) 2:36 7 No. 6b: Cepiny (Entry of the Bride) 1:56 8 No. 6c: Pie siuhajów (Drinking Song) 1:19 9 No. 7: Taniec góralski (The Tatra Highlanders’ Dance)* 4:20 0 No. 8: Napad harnasiów – Taniec (Raid of the Harnasie – Dance) 5:25 ! No. 9: Epilog (Epilogue)*† 2:39 Mandragora, Op. 43 27:04 8.557748 Text: Ryszard Bolesławski (1889-1937) and Leon Schiller (1887-1954) @ Scene 1**†† 10:38 # Scene 2†† 6:16 $ Scene 3** 10:10 % Knia Patiomkin (Prince Potemkin), Incidental Music to Act V, Op. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 122, 2002-2003

2002-2003 SEASON JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR DESIGNATE BERNARD HAJTINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR I OZAWA R LAUREATE BOSTON S Y M P H O 1ST ORCHESTRA Bring your Steinway: With floor plans from 2,300 Phase One of this magnificent to over 5,000 square feet, property is 100% sold and you can bring your Concert occupied. Phase Two is now Grand to Longyear. being offered by Sotheby's Enjoy full-service, single- International Realty and floor condominium living at its Hammond Residential Real absolute finest, all harmoniously Estate. Priced from $1,500,000. located on an extraordinary eight-acre Call Hammond Real Estate at gated community atop prestigious (617) 731-4644, ext. 410. Fisher Hill. LONGYEAR a / O^i'sJier Jfiff BROOKLINE «r a noisy world out there. ll ise above the din. r;:;^: • For almost twenty-five years, Sametz Blackstone has provided communications and design counsel to leading corporate, academic, and cultural organiza- tions-to build brand awareness, promote products and BSO, Tanglewood, Pops services, raise capital, and add measurable value. Boston Ballet FleetBoston Celebrity Series The need may be a comprehensive branding program Harvard University or a website, a capital campaign or an annual report. Through strategic consulting, thoughtful design, and Yale University innovative technology, we've helped both centenarians and start-ups to effectively communicate their messages Fairmont Hotels & Resorts offerings, and personalities-to achieve resonance-and American Ireland Fund be heard above the din. Scudder Investments / Deutsche Bank Raytheon Whitehead Institute / Genome Center Boston Public Library City of Boston Sametz Blackstone Associates Compelling communications—helping evolving organizations navigate change 40 West Newton Street Blackstone Square bla< kstone@sam< ' - ton 021 18 www.sametz.< om James Levine, Music Director Designate Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 122nd Season, 2002-2003 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

WNO Boheme Sim REORDER2 Print Spreads

WASHINGTON NATIONAL OPERA ORCHESTRA HEINZ FRICKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR Violin I Cello Clarinet Bass Trombone Oleg Rylatko, Amy Frost Baumgarten, David Jones, Principal Stephen Dunkel Concertmaster Principal Lora Ferguson, Assistant Eric Lee, Associate Elizabeth Davis,Assistant Principal Tuba/Cimbasso Concertmaster Principal Stephen Bates Michael Bunn, Principal Zino Bogachek+** Ignacio Alcover+ Joan Cataldo Amy Ward Butler Bass Clarinet Timpani Michelle Kim Timothy H. Butler** Stephen Bates Jonathan Rance, Principal Karen Lowry-Tucker Igor Zubkovsky Greg Akagi, Assistant Susan Midkiff Kerry Van Laanen* Bassoon Principal Washington National Opera’s Board of Trustees Margaret Thomas Donald Shore, Principal Charlie Whitten Bass Christopher Jewell, Percussion presents Doug Dube* Robert D’Imperio, Assistant Principal John Spirtas, Principal Jennifer Himes* Principal Nancy Stutsman Greg Akagi Patty Hurd* Frank Carnovale, Assistant Bill Richards* A Live Broadcast from Agnieszka Kowalsky* Principal Contrabassoon John Ricketts Nancy Stutsman Harp The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Violin II Jeffrey Koczela* Susan Robinson, Principal Julia Grueninger, Horn Sunday, September 23, 2007 Principal Flute Gregory Drone, Principal ADMINISTRATION Joel Fuller, Assistant Adria Sternstein Foster, John Peiffer, Assistant Principal Principal Principal Orchestra Personnel & Richard Chang+ Stephani Stang-Mc- Robert Odmark Operations Manager Xi Chen Cusker, Assistant Peter de Boor Aaron Doty Jessica Dan Fan Principal Geoffrey Pilkington Martha Kaufman -

WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide WTTW and WFMT have always synonymous with exceptional local content, and this month, we are The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT proud to bring you an especially impressive array of options – everything from three new installments Renée Crown Public Media Center of our own homegrown national music series Soundstage to an acclaimed play from Albany Park 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Theater Project and Goodman Theatre; thought-provoking documentaries about the city’s Cabrini Chicago, Illinois 60625 Green housing project and a secret WWII training exercise on Lake Michigan; an innovative film created Main Switchboard by a 12-year-old local filmmaker; and a new local series, The Interview (773) 583-5000 Show with Mark Bazer (wttw.com/interviewshow). Member and Viewer Services This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, there is something for everyone, (773) 509-1111 x 6 WFMT Radio Networks including American Masters profiles of Janis Joplin and the Highwaymen; a (773) 279-2000 new season of Genealogy Roadshow; That Bites!, a 12-year-old’s treatise on Chicago Production Center what it’s like to live with food allergies; a revealing series, Genius, hosted (773) 583-5000 by renowned physicist (and genius) Stephen Hawking; all-new webisodes Websites of Chat, Please! with David Manilow; the return of and final season with wttw.com Kenneth Branagh as the brooding Swedish detective Wallander and the wfmt.com continuation of our popular Saturday night mysteries; and two important President & CEO Independent Lens specials with town halls on gun violence in America. Daniel J. -

(KING ROGER) Opera in Three Acts by Karol Szymanowski Libretto by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz and the Composer Performed in Polish with German and English Surtitles

Premiere / First ever performance in Frankfurt KRÓL ROGER (KING ROGER) Opera in three acts by Karol Szymanowski Libretto by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz and the composer Performed in Polish with German and English surtitles Conductor: Sylvain Cambreling Director: Johannes Erath Set Designer: Johannes Leiacker Costume Designer: Jorge Jara Lighting Designer: Joachim Klein Video: Bibi Abel Chorus and Extra Chorus Master: Tilman Michael Children's Chorus Master: Markus Ehmann Dramaturge: Zsolt Horpácsy King Roger: Łukasz Goliński Roxana: Sydney Mancasola Sheperd: Gerard Schneider Edrisi: AJ Glueckert Archbishop: Alfred Reiter Deaconess: Judita Nagyová Oper Frankfurt's Chorus, Extra Chorus and Extras Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester The Polish composer Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) produced Król Roger (King Roger), the second and better known of his two operas, which received its World Premiere on June 19th 1926 at the Teatr Wielki in Warsaw. Despite its very unusual sound language it was not long before the work was being performed abroad. The libretto was written by the composer and his cousin, the poet Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, around their protagonist, King Roger II, descended of Norman noble lineage, who ruled in Sicily during the 12th century. The work, based on, amongst others, Euripides’ Bacchae, depicts a hero caught between the strict Christian church and a way of life more interested in pleasure. This is in keeping with views of the Mediterranean World, which had always fascinated Szymanowski. Interest in the work has never completely petered out, although this New Production is the first time the opera has ever been performed in Frankfurt. A young shepherd, a disciple of the god Dionysos, causes confusion at King Roger's court. -

“A New Mode of Expression”: Karol Szymanowski's First

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright “A NEW MODE OF EXPRESSION”: KAROL SZYMANOWSKI’S FIRST VIOLIN CONCERTO OP. 35 WITHIN A DIONYSIAN CONTEXT Marianne Broadfoot A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2014 I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. -

Die Meistersinger Von Nürnberg

DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG PRODUCTION TEAM BIOGRAPHY PAULE CONSTABLE, Lighting Designer Paule Constable (Lighting Designer) is an Associate Director of the National Theatre and an associate of the Lyric Hammersmith and for Matthew Bourneʼs New Adventures. She has been nominated for a further 6 Olivier awards and for a 2007 Tony Award for Coram Boy and a 2013 Tony for The Cripple of Inishmaan. She was the recipient of the Hospital Award for Contribution to Theatre and has also received the LA Drama Desk Award for Les Mis and for Warhorse; and both the New York Critics Circle Award and Drama Desk Award for both Curious Incident and Warhorse on Broadway. She was the first recipient of the Opera Award for Lighting in 2013. Opera includes Carmen, Faust, Rigoletto, The Marriage of Figaro, The Magic Flute and Macbeth for the Royal Opera House; Entfuhrung aus dem Serail, The Marriage of Figaro, The Cunning Little Vixen, Die Meistersinger, Billy Budd (also BAM), Rusalka, St Matthew Passion, Cosi Fan Tutti, Giulio Cesare (also Metropolitan Opera, New York), Carmen, The Double Bill and La Boheme at Glyndebourne; Benvenuto Cellini, Cosi fan Tutti, Medea, Idomeneo, Satyagraha (also Metropolitan Opera New York), Clemenza Di Tito, Gotterdamerung, The Rape of Lucretia ,The Rakes Progress and Manon for ENO; Cav and Pag, The Merry Widow, the Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni and Anna Bolena at the Metroplitan Opera, New York; Tales of Hoffman for Salzburg Festival; Poppea for Theatre Champs Elysees; Agrippina and A Midsummer Nightʼs Dream (La Monnaie); Cosi and The Ring Cycle for Opera National du Rhin, Tristan and Isolde for the New National Opera in Tokyo, Peter Grimes, Don Giovanni, La Traviata, Magic Flute and Rosenkavaliar for Opera North; Innes di Castro and Madama Butterfly at Scottish Opera and Don Giovanni, The Sacrifice and Katya Kabanova for WNO as well as productions throughout Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. -

Roger II, King of Heaven and Earth: an Iconological and Architectural Analysis of the Cappella Palatina in the Context of Medieval Sicily

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2018 Roger II, King of Heaven and Earth: An Iconological and Architectural Analysis of the Cappella Palatina in the Context of Medieval Sicily Mathilde Sauquet Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Sauquet, Mathilde, "Roger II, King of Heaven and Earth: An Iconological and Architectural Analysis of the Cappella Palatina in the Context of Medieval Sicily". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2018. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/741 Roger II, King of Heaven and Earth: An Iconological and Architectural Analysis of the Cappella Palatina in the Context of Medieval Sicily A Senior Thesis Presented by Mathilde Sauquet To the Art History Department In Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in Art History Advisor: Professor Kristin Triff Trinity College Hartford, Connecticut May 2018 Acknowledgments To Professor Triff, thank you for your guidance throughout my years at Trinity. It has been a pleasure working with you on this project which was so dear to my heart. Thank you to the brilliant faculty of the Art History Department for inspiring me to pursue a career in this field. To my friends, thank you for staying by my side always and offering comic relief and emotional support whenever I needed it. I could not have done it without you. To my family, thank you for believing in my dreams all these years. -

22 May 2015 Page 1 of 10

Radio 3 Listings for 16 – 22 May 2015 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 16 MAY 2015 Nederlands Kamerkoor, La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken SAT 13:00 Radio 3 Lunchtime Concert (b05vgxvc) (conductor) Musica Florea SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b05tq47b) Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra - Chaminade, 4:44 AM Czech early music ensemble Musica Florea perform sacred Mendelssohn Neruda, Johann Baptist Georg [c.1707-1780] works by Zelenka, Janacek, Tuma and Vanhal. Recorded in Concerto for horn or trumpet and strings in E flat major Rinchnach, Bavaria in 2014. Jaime Martin is the soloist in Chaminade's flute concerto and Tine Thing Helseth (trumpet), Oslo Camerata, Stephan Barratt- conducts the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Due (conductor) Mendelssohn's Fourth Symphony. With Jonathan Swain. SAT 14:00 Saturday Classics (b05vgxvf) 5:01 AM Diana Rigg 1:01 AM Andriessen, Hendrick (1892-1981) Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus [1756-1791] Concertino for cello and orchestra Dame Diana Rigg introduces a selection of music from around Concerto K.314 vers. flute & orch in D major Michael Müller (cello), Netherlands Radio Chamber Orchestra, the globe inspired by her career as an actress. She recalls some Jaime Martin (flute), Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Thierry Fischer (conductor) of the key events in her acting life with examples from the Jaime Martin (conductor) music that has often accompanied it. Her selection includes 5:12 AM music by Wolf-Ferrari, Smetana, Faure, John Barry, Mozart, 1:23 AM Handel, Georg Frideric (1685-1759) AR Ramen, Copland, Sondheim, Barber, Vaughan-Williams, Chaminade, Cecile [1857-1944] Tornami a vagheggiar - Act I Scene 15 from Alcina Karl Jenkins and Irving Berlin. -

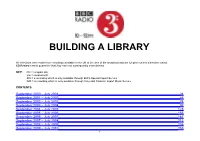

Building a Library

BUILDING A LIBRARY All selections were made from recordings available in the UK at the time of the broadcast and are full price unless otherwise stated. CD Review cannot guarantee that they have not subsequently been deleted. KEY: CD = compact disc c/w = coupled with SIS = a recording which is only available through EMI’s Special Import Service IMS = a recording which is only available through Universal Classics' Import Music Service CONTENTS September 2000 – July 2001 .................................................................................................................................. 24 September 2001 – July 2002 .................................................................................................................................. 46 September 2002 – July 2003 .................................................................................................................................. 74 September 2003 – July 2004 .................................................................................................................................. 98 September 2004 – July 2005 ................................................................................................................................ 128 September 2005 – July 2006 ................................................................................................................................ 155 September 2006 – July 2007 ............................................................................................................................... -

Cloud Light Review

same thing in trusting this revival of Il Signor Fortunately, the rest of the cast is not Cloud Light – Songs of Norbert Palej Bruschino to a young theatre group, Teatro outclassed by Netrebko’s radiance. Te great Bogdanowicz; McGillivray; Wiliford; Sotteraneo, with no previous experience in basso René Pape (Banquo) is a distinguished Woodley; Philcox opera. Te directors of the group are all in credit to a rather short role (as he gets killed Centrediscs CMCCD 22315 their 20s and full of ideas, energy and fun. quickly) and so is the tenor, Joseph Calleja Te scene for this one-act farsa giocosa is a (Macduff), but at least he survives. Serbian ! Te song or modern-day theme park complete with Coke baritone Zeljko Lucic (Macbeth) is a fine chanson or lied machines, popcorn, balloons and silly hats. character actor with a strong voice, but no died with Benjamin Tourists of all ages wander in and out snap- match for the great Italian baritones (e.g. Britten – or that is the ping photos and are invited to join in the Leo Nucci or Renato Bruson) of yesteryear. impression you might even sillier plot where everyone lies except Exciting yet sensitively refined conducting have gotten by visiting the poor put-upon protagonist, Bruschino. In by new Met principal conductor Fabio Luisi your neighbourhood fact they confuse him so much that he ends amply compensates for the still unsurpassed record store or any up wondering who he is and there is typical legendary Sinopoli reading. concert hall. While Rossinian mayhem, except for the wonderful Janos Gardonyi Brahms, Strauss, Schubert and Mahler song music and the singing.