Milwaukee County-Funded Parks and Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ald. Michael Murphy Chair, Milwaukee Arts Board

Department of City Development 809 North Broadway, Milwaukee, WI 53202 (414) 286-5794 Fax (414) 286-5467 Tom Barrett, Mayor Ald. Michael Murphy, Chair www.milwaukee.gov/MAB Contact: Ald. Michael Murphy Chair, Milwaukee Arts Board (414) 286-2074 For Immediate Release City of Milwaukee Arts Board awards $238,000 to 35 arts organizations Summer arts programs for youth, free performances of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, and a series of cross-neighborhood dinners in connection with the classic American play Our Town are among 35 projects awarded funding recently by the City of Milwaukee Arts Board. At its May meeting the MAB considered the recommendations of an eight-member citizen review panel and voted to award $238,000 in grants ranging from $3,500 to $7,000. MAB grants require a dollar-for-dollar cash match from other sources, and the combined budgets of the 35 selected projects this year is more than $3.48 million. There were a total of 41 eligible requests from Milwaukee nonprofit arts organizations to fund art, music, dance, arts education and other projects. “I’m always impressed by the quality work our local arts community puts forth,” said Ald. Michael Murphy, Milwaukee Arts Board Chair. “We’re pleased to be able to support their efforts.” This year marks the 27th annual grant awards. Since 1991, the Milwaukee Arts Board has awarded more than $4.95 million to 127 different organizations. Grantees will be honored by Mayor Tom Barrett, Ald. Murphy and others at a 4:30 p.m. reception June 12 at the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts followed by an awards program and celebration at 5 p.m. -

The Artifact

The Artifact A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America - Milwaukee Society Vol. 13 No. 2 Contents Letter from the President Letter from the President 1 - 2 Dr. Derek B. Counts, Assistant Professor of Power, Ideology, and the Emergence of the State in Classical Art and Archaeology, University of the Oaxaca Valley, Mexico 3 Wisconsin - Milwaukee The Archaeological Excavations at Kilteasheen, Ireland 4 Happy New Year and Greetings from the Blood and Power: Arena Spectacle and the Roman Milwaukee Society of the AIA. They say that Empire 5 in life few things are guaranteed; while that may be true for credit card interest rates and a The Forty Years of AIA in Milwaukee 6 - 8 Packers victory over New York, you can always count on a full and diverse annual Cyprus & the Antiquities Trade: An Interview lecture program from the Milwaukee Society! with Dr. Pavlos Flourentzos 8 - 10 On Sunday, February 10 we welcome th Professor Jason Sherman from UWM’s 109 Archaeological Institute of America Annual Meeting 11 Anthropology Department (local talent!), who will speak to us on recent archaeological work AIA-Milwaukee’s Field Trip to Oriental Institute in the Oaxaca Valley (Mexico) and what it can Museum 11 tell us about the emergence of the Zapotec state in the later first millennium B.C.E. In AIA-Milwaukee Society Lecture Calendar 12 March and April, we will host Professors Thomas Finan (Saint Louis University) and 2007-2008 Milwaukee Officers Alison Futrell (University of Arizona). On Derek Counts, President Sunday March 2, Professor Finan will [email protected] highlight the latest discoveries at Kilteasheen, Bettina Arnold, Vice-President Co. -

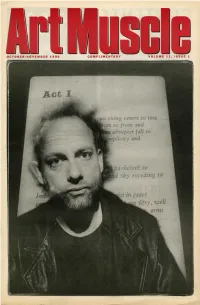

UWM Libraries Digital Collections

OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 1996 COMPLIMENTARY VOLUME 1 1, ISSUE 1 CASTS OF CONTENTS CHARACTER ;Sfe5 m wm ::ft|f liiiiiiii! isiSiiiaiia ^m W 5S** m till ®m ililii*****"" . .•li.'-ftiiiill '"* •'• : "*"****> €15116 "^""^^feiSS?**! *£& Robert Cottingham, Art (detail), 1992. MAM, Landfall Press Archive, Gift of Jack Lemon. An Exhibition Featuring the Work of Former Artists-in-Residence in the FEHTU RES John Michael Kohler Arts Center's Arts/Industry Program at Kohler Co. Reflections on the Milwaukee Art Museum 12 September 29,1996 - January 5,1997 Photographs by Francis Ford 14 A Tale of Two Cities: Milwaukee vs. Milwaukee 16 TRE' ARENZ • LAWRENCE ARGENT • NANCY DWYER It Could Have Been a Parking Lot 17 PETER FLANARY • LESLIE FRY • MICHAEL GARR Beyond Bovines 18 MARTHA GLOWACKI • RONALD GONZALEZ INDIRA FREITAS JOHNSON • KEN LITTLE A Fine Line 19 EVA MELAS • CINDI MORRISON • JOEL OTTERSON Reflections on the Haggerty Museum of Art 20 CAROLYN OTTMERS • ALBERT PFARR • PAUL SEBBEN Fixing The Leaks 21 BUSTER SIMPSON • JANET WILLIAMS • ANDY YODER Essay/Steven Foster/Studies 22 OPENING CELEBRATION DEPARTMENTS Friday, October 4,1996 • 5:30-8:30 p.m. Refreshments • Music by The Mosleys Plexus/Reflexus 4 Free Admission Grants/Opportunities 6 Post Facto 24 Concurrent Exhibitions Calendar/Out There 28 Anna Torma: Notes and Visions Madison/Chicago 33 Kate Moran: Nine Dolls Full of Color Who Understand Touch through October 27 Rudy Rotter: Mahogany to Mink November 3, 1996 - February 2, 1997 ON THE COVER Opening and Exhibition Preview Front: David Schweitzer, Director, 1986. Photograph by Francis Ford. with Rudy Rotter and Guest Curator Debra Brehmer Back: Les Petite Bon-Bon, 1971. -

Casas Grandes Ceramics at the Milwaukee Public Museum

Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology Volume 11 Article 10 2021 Casas Grandes Ceramics at the Milwaukee Public Museum Samantha A. Bomkamp University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Linguistic Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Bomkamp, Samantha A. (2021) "Casas Grandes Ceramics at the Milwaukee Public Museum," Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology: Vol. 11 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes/vol11/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology Volume 11 Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology Volume 11 Number 1 May 2021 Published by the Anthropology Student Union (ASU) at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, USA Editor-in-Chief Ann S. Eberwein Editors Ashley Brennaman Heather Brinkman Cody Schumacher Jessica Skinner Editorial Committee Karissa Annis Laya Liebeseller Bill Balco Ciaran McDonnell Sarah Boncal Cheri Price Josh Driscoll Joshua Rivers Adrienne Frie Katherine Santell Kevin Gartski Katrina Schmidt Dominic Greenlee Tony Schultz Alexis Jordan Faculty -

The Milwaukee Public Museum's Leopardi Collection

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2017 Melita in Milwaukee: the Milwaukee Public Museum’s Leopardi Collection Stephan Noureddine Hassam University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Hassam, Stephan Noureddine, "Melita in Milwaukee: the Milwaukee Public Museum’s Leopardi Collection" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1483. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1483 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MELITA IN MILWAUKEE: THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM’S LEOPARDI COLLECTION by Stephan Noureddine Hassam A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2017 ABSTRACT MELITA IN MILWAUKEE: THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM’S LEOPARDI COLLECTION by Stephan Noureddine Hassam The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold The Phoenician/Punic occupation of Malta is an important period in the nation’s history. The Phoenicians first settled the Maltese islands sometime in the early to late seventh century B.C., and their material culture left a lasting influence on the island for nearly a millennium. Beginning in the early 1600s, Phoenician material culture began to be recognized as such. Following wider trends in the Enlightenment era in Europe, Maltese nobility and clergy began collecting antiquities. -

A Preliminary Museological Analysis of the Milwaukee Public Museum's

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2015 A Preliminary Museological Analysis of the Milwaukee Public Museum's Euphrates Valley Expedition Metal Collection Jamie Patrick Henry University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Henry, Jamie Patrick, "A Preliminary Museological Analysis of the Milwaukee Public Museum's Euphrates Valley Expedition Metal Collection" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1054. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1054 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PRELIMINARY MUSEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM’S EUPHRATES VALLEY EXPEDITION METAL COLLECTION by Jamie Patrick Henry A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2015 ABSTRACT A PRELIMINARY MUSEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM’S EUPHRATES VALLEY EXPEDITION METAL COLLECTION by Jamie Patrick Henry The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold Destruction of ancient sites along the Euphrates River in northern Syria due to the construction of the Tabqa Dam and the formation of Lake Assad led to many international salvage expeditions, including those conducted between 1974 and 1978 by the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) at the site of Tell Hadidi, Syria under the direction of Dr. -

Joel W. Palka Curriculum Vitae

JOEL W. PALKA CURRICULUM VITAE CURRENT POSITION HOME ADDRESS Associate Professor 8850 S Los Feliz Dr. School of Human Evolution and Social Change Tempe, AZ 85284 Arizona State University 708-602-0154 900 S. Cady Mall, #233 1/23/2020 Tempe, AZ 85287-2402 (480) 965-1052 [email protected] POSITIONS HELD 2018-present Associate Prof., School of Human Evolution and Social ChanGe, Arizona State University (ASU) 2018 Interim Director, Latin American and Latino Studies, UIC (SprinG semester; summer) 2014-2018 Professor, Anthropology/Latin American and Latino Studies, University of Illinois-ChicaGo (UIC) 2016 ActinG Director, Latin American and Latino Studies, UIC (Spring semester) 2014-2015 ActinG Head, AnthropoloGy, University of Illinois-ChicaGo (ended Jan. 15, 2015) 2005-2014 Associate Professor, AnthropoloGy and Latin American and Latino Studies, UIC 1999-2018 Adjunct Curator, AnthropoloGy, The Field Museum 1999-2005 Assistant Professor, AnthropoloGy and Latin American and Latino Studies, UIC 1996-1999 VisitinG Assistant Professor, AnthropoloGy and Latin American Studies, UIC 1996-1999 Research Associate, AnthropoloGy, The Field Museum 1995-1996 VisitinG Assistant Professor, AnthropoloGy, Vanderbilt University RESEARCH INTERESTS Mesoamerica; Maya archaeoloGy and ethnohistory; unconquered Maya history and culture; Maya hieroGlyphs and art; culture contact and culture change; social inequality; historical archaeology; colonialism in Latin America; pilgrimaGe; indigenous archaeology and history; political collapse; anthropology of art; ceramics; -

Ald. Michael Murphy Chair, Milwaukee Arts Board

Department of City Development 809 North Broadway, Milwaukee, WI 53202 (414) 286-5794 Fax (414) 286-5467 Tom Barrett, Mayor Ald. Michael Murphy, Chair www.milwaukee.gov/MAB Contact: Ald. Michael Murphy Chair, Milwaukee Arts Board (414) 286-2074 For Immediate Release City of Milwaukee Arts Board announces 2016 Artists of the Year and Friends of the Arts Awards Della Wells and Dasha Kelly have been named 2016 Artists of the Year, the City of Milwaukee Arts Board announced recently. Thallis Hoyt Drake and Andy Nunemaker were named 2016 Friends of the Arts. They will be honored Tuesday, June 14 at a 4:30 p.m. reception in the atrium of the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts followed by an awards program and celebration at 5 p.m. Representatives of 33 city-based arts organizations who received arts board grants will also be honored. “We’re glad to shine a light on these four individuals, who have contributed so much to our entire community,” said Ald. Michael Murphy, who chairs the Milwaukee Arts Board. Della Wells is a self-taught artist who began drawing and painting in earnest at the age of 42. Her work ranges from collage and pastels to quilting. Her creative process stems from her personal experiences embellished through the art of storytelling. In 2011, an award winning play inspired by her life, '' Don't Tell Me I Can't Fly'', premiered in Milwaukee. The play was commissioned by First Stage children’s theater and written by Y York. She illustrated a children's book, "Electric Angel" by Nanci Mortimer, to be released by Wooden Nickel Press in late June. -

Editorial and Design Principles in Precursors Of

PRECURSORS TO THE RISE OF ENGLISH WORLD ATLASES; Theatres, Atlases, Cosmographies, Geographies, and Sets of Maps Dalia Varanka, Research Geographer U.S. Geological Survey 1400 Independence Road Rolla, Mo 65401 Tel. 573.308.3897 Email [email protected] Acnowledgement: This paper is based on doctoral dissertation research formulated under the supervision of J.B. Harley. The dissertation work was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation and with fellowships from the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University; the Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography, The Newberry Library; and the Graduate College of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The context of the rise of world atlases in England suggests that they were tied to wider scholarly and social issues covering the period of roughly 1630 through 1730. This short history discusses the cosmographical background and Continental foundations of the rise of world atlases in England, and a survey of relevant English precursors to those atlases. A risk exists of rooting definitions of atlases firmly in cartography, subsuming other defining concepts, such as scientific philosophy and social values. An alternative way to look at atlases is that they are part of the larger corpus of their other contemporary works. The word ‘atlas’ was applied to only a part of our extant corpus of bound or unbound collections of maps of the world made in late seventeenth- century England. A more frequent term is "set of maps," (or Tabularum Geographicarum). ‘Geography’ is also used. Bound sets of maps, which are called Atlas Factice, are almost never called atlases by their makers or producers. -

I Aeronautical Engineerfrljaer 3 I

k^B* 4% Aeronautical NASA SP-7037 (103) Engineering December 1978 A Continuing SA Bibliography with Indexes National Aeronautics and Space Administration • L- I Aeronautical EngineerfrljAer 3 i. • erjng Aeronautical Engineerjn igineering Aeronautical Engim cal Engineering Aeronautical E nautical Engineering Aeronaut Aeronautical Engineering Aen sring Aeronautical Engineerinc . gineering Aeronautical Engine ;al Engineering Aeronautical E lautical Engineering Aeronaut Aeronautical Engineering Aerc ring Aeronautical Engineering ACCESSION NUMBER RANGES Accession numbers cited in this Supplement fall within the following ranges: STAR(N-10000 Series) N78-30038—N78-32035 IAA (A-10000 Series) A78-46603—A78-50238 This bibliography was prepared by the NASA Scientific and Technical Information Facility operated for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration by Informatics Information Systems Company. NASA SP-7037(103) AERONAUTICAL ENGINEERING A Continuing Bibliography Supplement 103 A selection of annotated references to unclas- sified reports and journal articles that were introduced into the NASA scientific and tech- nical information system and announced in November 1978 m • Scientific and Technical Aerospace Reports (STAR) • International Aerospace Abstracts (IAA) Scientific and Technical Information Branch 1978 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC This Supplement is available from the National Technical Information Service (NTIS). Springfield. Virginia 22161. at the price code E02 ($475 domestic. $9.50 foreign) INTRODUCTION Under the terms of an interagency agreement with the Federal Aviation Administration this publication has been prepared by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for the joint use of both agencies and the scientific and technical community concerned with the field of aeronautical engineering. The first issue of this bibliography was published in September 1970 and the first supplement in January 1971 Since that time, monthly supplements have been issued. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 1 2 Annual Report 2005 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 www.mam.org 1 2 Annual Report 2005 Contents Board of Trustees . 4 Committees of the Board of Trustees . 4 President and Chairman’s Report . 6 Director’s Report . 9 Curatorial Report . 11 Exhibitions, Traveling Exhibitions . 14 Loans . 14 Acquisitions . 16 Publications . 35 Attendance . 36 Membership . 37 Education and Public Programs . 38 Year in Review . 39 Development . 43 Donors . 44 Support Groups . 51 Support Group Officers . 55 Staff . 58 Financial Report . 61 Financial Statements . 63 OPPOSITE: Ludwig Meidner, Self-Portrait (detail), 1912. See listing p. 16. PREVIOUS PAGE: Milwaukee Art Museum, Quadracci Pavilion designed by Santiago Calatrava as seen looking east down Wisconsin Avenue. www.mam.org 3 Board of Trustees As of August 30, 2005 BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEES OF Earlier European Arts Committee Jean Friedlander AND COMMITTEES THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jim Quirk Milton Gutglass George T. Jacobi MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair David Ritz Sheldon B. Lubar Sheldon B. Lubar Martha R. Bolles Helen Weber Chairman Chair Vice Chair and Secretary Barry Wind Andrew A. Ziegler Christopher S. Abele Barbara B. Buzard EDUCATION COMMITTEE President Donald W. Baumgartner Joanne Charlton Lori Bechthold Margaret S. Chester Christopher S. Abele Donald W. Baumgartner Frederic G. Friedman Stephen Einhorn Chair Vice President, Past President Terry A. Hueneke George A. Evans, Jr. Kim Abler Mary Ann LaBahn Eckhart Grohmann Frederic G. Friedman John Augenstein Marianne Lubar Frederick F. Hansen Assistant Secretary and James Barany P. M ichael Mahoney Avis M. Heller Legal Counsel José Chavez Betty Ewens Quadracci Arthur J. Laskin Terrence Coffman Mary Ann LaBahn James H. -

Redalyc.Contribution to a History of Mexican Dipterology Part II.- The

Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) ISSN: 0065-1737 [email protected] Instituto de Ecología, A.C. México Papavero, Nelson; Ibáñez Bernal, Sergio Contribution to a History of Mexican Dipterology Part II.- The Biologia Centrali-Americana Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), núm. 88, 2003, pp. 143 - 232 Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Xalapa, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57508806 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Acta Zool. Mex. (n.s.) 88:143-232 (2003) CONTRIBUTIONS TO A HISTORY OF MEXICAN DIPTEROLOGY. PART II.- THE BIOLOGIA CENTRALI-AMERICANA Nelson PAPAVERO1 & Sergio IBÁÑEZ-BERNAL2 1 Museu de Zoologia & Instituto de Estudos Avançados, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, BRAZIL Pesquisador do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Proc. Nº 1 300994/79) 2 Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Departamento de Entomología, km 2.5 carretera antigua a Coatepec N/ 351, Congregación El Haya, 91070, Xalapa, Veracruz, MÉXICO RESUMEN En esta segunda contribución a la historia de la Dipterología mexicana, se presentan datos generales de la obra Biologia-Centrali Americana, de sus autores, colectores y de los viajes efectuados para la obtención del material. Específicamente con respecto a Diptera, se incluyen algunos aspectos de la vida y obra de los contribuidores de este trabajo. Aquí se enlistan todos los nombres de especies de los Diptera mexicanos propuestos por Karl Robert Romanovitch Baron von den Osten Sacken (78 especies), Samuel Wendell Williston (200 especies), John Merton Aldrich (47 especies), William Morton Wheeler y Axel Leonard Melander (18 especies), y Frederik Maurits Van Der Wulp (610 especies).