Dutch Versus Portuguese Colonialism. Traders Versus Crusaders?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Construçao Do Conhecimento

MAPAS E ICONOGRAFIA DOS SÉCS. XVI E XVII 1369 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] Apêndices A armada de António de Abreu reconhece as ilhas de Amboino e Banda, 1511 Francisco Serrão reconhece Ternate (Molucas do Norte), 1511 Primeiras missões portuguesas ao Sião e a Pegu, 1. Cronologias 1511-1512 Jorge Álvares atinge o estuário do “rio das Pérolas” a bordo de um junco chinês, Junho I. Cronologia essencial da corrida de 1513 dos europeus para o Extremo Vasco Núñez de Balboa chega ao Oceano Oriente, 1474-1641 Pacífico, Setembro de 1513 As acções associadas de modo directo à Os portugueses reconhecem as costas do China a sombreado. Guangdong, 1514 Afonso de Albuquerque impõe a soberania Paolo Toscanelli propõe a Portugal plano para portuguesa em Ormuz e domina o Golfo atingir o Japão e a China pelo Ocidente, 1574 Pérsico, 1515 Diogo Cão navega para além do cabo de Santa Os portugueses começam a frequentar Solor e Maria (13º 23’ lat. S) e crê encontrar-se às Timor, 1515 portas do Índico, 1482-1484 Missão de Fernão Peres de Andrade a Pêro da Covilhã parte para a Índia via Cantão, levando a embaixada de Tomé Pires Alexandria para saber das rotas e locais de à China, 1517 comércio do Índico, 1487 Fracasso da embaixada de Tomé Pires; os Bartolomeu Dias dobra o cabo da Boa portugueses são proibidos de frequentar os Esperança, 1488 portos chineses; estabelecimento do comércio Cristóvão Colombo atinge as Antilhas e crê luso ilícito no Fujian e Zhejiang, 1521 encontrar-se nos confins -

The Ottoman Age of Exploration

the ottoman age of exploration the Ottomanof explorationAge Giancarlo Casale 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dares Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Casale, Giancarlo. Th e Ottoman age of exploration / Giancarlo Casale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-537782-8 1. Turkey—History—16th century. 2. Indian Ocean Region—Discovery and exploration—Turkish. 3. Turkey—Commerce—History—16th century. 4. Navigation—Turkey—History—16th century. I. Title. DR507.C37 2010 910.9182'409031—dc22 2009019822 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper for my several -

The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500-1800

THE PORTUGUESE, INDIAN OCEAN AND EUROPEAN BRIDGEHEADS 1500-1800: Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K.S. Mathew Edited by: Pius Malekandathif Jamal Mohammed FUNDACAO CRIENTE FUNDACAO CRIENTE Funda?ao Oriente is a Portuguese private institution that aims to carry out and support activities of a cultural, artistic, educational, philanthropic and social nature, principally in Portugal and Asia. Within these general aims, the Fundagao Oriente seeks to maintain and strengthen the historical and cultural ties between Portugal and countries of Eastern Asia, namely the People's Republic of China, India, japan, Korea, Thailand, Malayasia and Sri Lanka. The Funda^ao Oriente has its head quarters in Lisbon, with Delegations in China (Beijing and Macao) and India (Coa). © Editors ISBN 900166-5-2 The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads, 1500-1800: Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K,S. Mathew Edited by: Pius Malekandathil T. jamal Mohammed First Published in 2001 by: Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR, Post box No. 70, TeHicherry - 670101 Kerala, India. Printed at : Mar Mathews Press, Muvattupuzha - 686 661, Kerala 20 DECLINE OF THE PORTUGUESE NAVAL POWER : A STUDY BASED ON PORTUGUESE DOCUMENTS K. M. Mathew Portugal was the spearhead of European expansion. It was the Portuguese who inagurated the age of renaissance- discovery and thus initiated the maritime era of world history. There is hardly any period in world history as romantic in its appeal as this ‘ Age of Discovery ’ and hence it is of perennial interest. The Portuguese achievement in that age is a success story which has few parallels. That they achieved what they set forth - “possessing the sources of the spice-trade and its diversion to European markets” -is a great feat for a country of her size, population and resources. -

Portuguese Empire During the Period 1415-1663 and Its Relations with China and Japan – a Case of Early Globalization

JIEB-6-2018 Portuguese empire during the period 1415-1663 and its relations with China and Japan – a case of early globalization Pavel Stoynov Sofia University, Bulgaria Abstract. The Portuguese Colonial Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lived empires in world history. It existed for almost six centuries, from the capture of Ceuta in 1415, to the handover of Portuguese Macau to China in 1999. It is the first global empire, with bases in North and South America, Africa, and various regions of Asia and Oceania(Abernethy, 2000). The article considers the contacts between Portugal, China and Japan during the first imperial period of Portuguese Empire (1415-1663). Keywords: Portuguese Colonial Empire, China, Japan Introduction The Portuguese Colonial Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lived empires in world history. It existed for almost six centuries, from the capture of Ceuta in 1415, to the handover of Portuguese Macau to China in 1999. It is the first global empire, with bases in North and South America, Africa, and various regions of Asia and Oceania(Abernethy, 2000). After consecutive expeditions to south along coasts of Africa, in 1488 Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and in 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India. Over the following decades, Portuguese sailors continued to explore the coasts and islands of East Asia, establishing forts and factories as they went. By 1571 a string of naval outposts connected Lisbon to Nagasaki along the coasts of Africa, the Middle East, India and South Asia. This commercial network and the colonial trade had a substantial positive impact on Portuguese economic growth (1500–1800), when it accounted for about a fifth of Portugal's per-capita income (Wikipedia, 2018). -

UQ684634 OA.Pdf

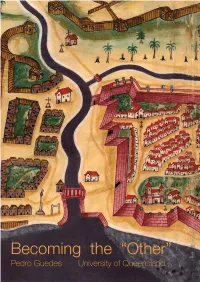

Pedro Guedes (2017) ‘Becoming the Other’, Lee Kah-Wee, Chang Jiat-Hwee, Imran bin Tajudeen (Convenors) M O D E R N I T Y ’ S ‘ O T H E R ’ Disclosing Southeast Asia’s Built Environment across the Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, 2nd SEAARC Symposium, National University of Singapore, 5-7 January, 2017, preprint. CONTENTS: Text 1 Presentation powerpoint slides 19 Conference abstracts & publication details 30 ABSTRACT Malacca (Melaka) entered the modern age violently on July 1st, 1511, when Afonso de Albuquerque salvoed his guns at the city as he blockaded the port. The siege was short and brutal. Its success, gained by 900 Portuguese and 200 Hindu mercenaries in eighteen ships, took the locals by complete surprise thinking the force puny compared to the 20,000 men with 20 war elephants and an impressive arsenal of artillery ranged against them. Even though the Portuguese had only been in Asia for just over a decade, they had been quick to appreciate Malacca’s strategic importance as a trading hub. A point of exchange for valuable cargoes from the archipelago to the South and Chinese ports to the East, it was located strategically between two legs of the monsoon trade cycles. Controlling the Straits fell in with Albuquerque’s ambition to regulate and tax all shipping on this route by the savage enforcement of safe-conduct navigational ‘cartazes’ to be issued by the Portuguese who considered the Indian Ocean and Asian seas as their Sovereign territory. To implement this regime, the Portuguese needed a strategically placed fortified base to assemble fleets and levy duties, enforced by superior naval gunnery and ruthless tactics. -

Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire Free

FREE CONQUERORS: HOW PORTUGAL FORGED THE FIRST GLOBAL EMPIRE PDF Roger Crowley | 432 pages | 04 Aug 2016 | FABER & FABER | 9780571290901 | English | London, United Kingdom Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire (Roger Crowley) • The Worthy House Afonso de Albuquerque died years ago, after spending a dozen years terrorizing coastal cities from Yemen to Malaysia. He enriched thousands of men and killed tens of thousands more. Despite never commanding more Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire a few dozen ships, he built one of the first modern intercontinental empires. Perhaps, he mused, he could destroy Islam altogether. It is a classic ripping yarn, packed with excitement, violence and cliffhangers. Its larger-than-life characters are at once extraordinary and repulsive, at one moment imagining the world in entirely new ways and at the next braying with delight over massacring entire cities. At Mombasa in the Portuguese killed Muslims with a loss of five of their own men. The biggest of these is surely how a handful of Europeans managed, for good and ill, to do so much. Crowley does not give us an explicit answer, but he provides more Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire enough information for readers to make up their own minds. Some historians have suggested that Albuquerque owed his success more to divisions within India than to any European advantages, but Crowley makes it clear that infighting among the Portuguese was even worse. The theory that Christian civilization Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire simply superior to Muslim and Hindu cultures seems equally unconvincing. -

Redalyc.CHINESE COMMODITIES on the INDIA ROUTE in the LATE 16TH – EARLY 17TH CENTURIES

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Loureiro, Rui Manuel CHINESE COMMODITIES ON THE INDIA ROUTE IN THE LATE 16TH – EARLY 17TH CENTURIES Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, vol. 20, junio, 2010, pp. 81-94 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36129852004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2010, 20, 81-94 CHINESE COMMODITIES ON THE INDIA ROUTE IN THE LATE 16TH – EARLY 17TH CENTURIES Rui Manuel Loureiro Centro de História de Além-Mar & Instituto Superior Manuel Teixeira Gomes Abstract This text briefly covers some of the issues related to the movement of Chinese goods on the India route – the Carreira da Índia – in the late 16th and early 17th cen- turies. Essentially it raises issues concerning more practical aspects of the trade in goods originating in China, from their shipment in Malacca until they reached the European ports, having travelled a very long distance by sea, a journey that could take as long as two years, with shorter or longer stopovers in Macao and Goa. Many of the records referring to this maritime trade disappeared without a trace. Most were engulfed by the infamous Lisbon earthquake of 1755 which destroyed the India House – or Casa da Índia – and its priceless archives. Alternative sources have then to be sought, a process that is attempted in this survey. -

Timeline / 400 to 1700 / PORTUGAL

Timeline / 400 to 1700 / PORTUGAL Date Country | Description 555 A.D. Portugal Reorganisation of the Suebian Church by Saint Martin of Dumes. 610 A.D. Portugal Birth of Saint Fructuosus of Braga. 633 A.D. Portugal Liturgical unification of Hispania. 711 A.D. Portugal Start of the islamicisation of al-Andalus. First incursions in al-Gharb. 763 A.D. Portugal Abbasid revolt in Beja, which quickly spreads to all of al-Gharb. 844 A.D. Portugal Normans attack the Portuguese coast. 868 A.D. Portugal Start of the Muladi revolts against their Umayyad rulers in the west of the peninsular. 929 A.D. Portugal ‘Abd al-Rahman III lays siege to Beja and Faro. Establishment of the Caliphate of Córdoba. 1013 A.D. Portugal Appearance of the first taifa kingdoms in al-Andalus. 1044 A.D. Portugal Abbasid campaigns in the south. Conquest of Lisbon and Mértola. 1064 A.D. Portugal Sisnando takes Coimbra. 1080 A.D. Portugal Council of Burgos abolishes the Mozarabic rite in favour of the Roman rite. Date Country | Description 1095 A.D. Portugal Establishment of the Portucuese Counties. 1111 A.D. Portugal Consolidation of Almoravid power in the southwest of the peninsula. Attack on Coimbra. 1128 A.D. Portugal Battle of São Mamede. Afonso Henriques takes control of the Portucuese Counties. 1143 A.D. Portugal Second taifas in al-Gharb. Afonso Henriques recognised as king at the Zamora Conference. 1147 A.D. Portugal Conquest of Lisbon and Santarém. 1153 A.D. Portugal Foundation of the abbey at Alcobaça. 1156 A.D. Portugal Almohad dominance in the south. -

Why Were the Portuguese Once Called the “Heroes of the Sea?”

FYI FEATURE Heroes of the Sea Question: Why were the Portuguese once called the “Heroes of the Sea?” A n sw er : of Africa, leading to the discovery of The Portuguese were once called several uninhabited islands and the the heroes of the sea because of the conquest of several African territories. discoveries and conquests they carried When the Portuguese navigator out some centuries ago. Bartolomeu Dias turned the Cape of During the 15th and 16th centu- Good H ope in Southern Africa in 1488, ries, Portugal experienced a golden age it opened the maritime route to I ndia of discoveries, mainly due to the push of and contradicted Christopher Columbus’ the Portuguese kings, princes and other idea of reaching I ndia from the west. As renowned navigators. a result of Dias enterprise, some years One of the main reasons for later the famous Portuguese navigator, Portugal’s expansion seawards was Vasco da Gama, sailed to I ndia where because it was impossible to expand or he arrived in Calicut on M ay 20, 1498. reach new markets except by sea, since I n 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon sighted the Brazilian coast and ten controlled the territory outside the land years later Afonso de Albuquerque borders of Portugal at the time. This conquered the I ndian State of Goa in Portuguese expansion overseas resulted the M alabar Coast, which was annexed in the first and largest colonial empire of by the Republic of I ndia in 1962. the 15th and 16th century. Besides the above mentioned The Portuguese empire began territories, the Portuguese explorers also granted independence after the 1974 around 1415 when the Portuguese fleet discovered or conquered other impor- military coup that restored democracy in organized by H enry the N avigator, tant territories in Africa, the Far East, Portugal that had been lost 47 years prince of Portugal, explored the west and Southern Asia and reached China before. -

The Role of Interpreters, Or Linguas, in the Portuguese Empire During the 16Th Century

The Role of Interpreters, or Linguas, in the Portuguese Empire During the 16th Century Dejanirah Couto École Pratique des Hautes Études Section des Sciences Historiques et Philologiques – Paris [email protected] Abstract This article analyses the different categories of interpreters (lingoas), the forms of their recruitment and the strategies of their use in the Portuguese Empire in Asia in the first half of the sixteenth century. The interpreters were as good as adventurers, convicts and natives, captives, renegades and converted slaves recruited during expeditions and military operations. Besides the social-economical status of these interpreters the article highlights the case of the territory of Macao where the necessity to answer to imperial bureaucracy determines the creation of a corps of interpreters (jurubaças) and perfectly organised family dynasties of "lingoas". Keywords Renegades, Convicts, Interpreters, Jews, New-christians Slaves, Languages, Conversions, Translation, Lingoas, Jurubaças Former renegades and captives, natives and converted slaves, Jews and new Christians, adventurers and convicts formed an important contingent of a specific category inside the frontier society of the Portuguese empire: that of the interpreters or linguas. Their functions could be executed by those who were not marginal, but the ideal profile required to competently fulfill this position presented some characteristics such as the facility to evolve in several worlds, which was not a quality found in the milieux of the imported society. Furthermore, there were several technical problems. Individuals with proficiency in Eastern languages were rare in Portugal; only some merchants, men of letters or religion who had traveled could occasionally be used as interpreters. The languages known in these milieux were also limited. -

1 Introduction 2 Revisiting the Creole Port City

Notes 1 Introduction 1 . See my book manuscript, tentatively titled “Kuala Lumpur, Myanmar City: Cosmopolitanism in an Indian Ocean Postcolony.” 2 . Incidentally, matrilineality as an Indian Ocean or Atlantic research subject seems to be scarce to nonexistent. It is, nonetheless, difficult to believe that matrilineality should never travel, even when people who are matrilineal clearly did, as in the case of the Minangkabau or the vari- ous groups, both Hindu and Muslim, of the Malabar Coast. There is an interesting historical counterpoint here between patrilineal male outsid- ers and matrilineal local female ancestors, as in the case highlighted by Ghosh (1993) for Malabar, but also in the case of Senegambian and other societies. 3 . See Assubuji and Hayes (2013) for an article on the life of Kok Nam, a Chinese Mozambican photographer belonging to the Guangdong diaspora. 4 . I must add here that Goans often cannot trace that connection either, at least not in terms of an ethnic ancestry. That is the case of the Le ã o family men- tioned above. In fact, when I once pressed Dr Má rio Le ã o about the ultimate origins of his family, he mentioned Afonso de Albuquerque’s famous policies of the 1510s (sic), whereby Portuguese men were encouraged or made to marry local women. This story is very much reminiscent of that of the ori- gin of Melakan Portuguese families, also supposedly somehow tracing their ancestry back to Albuquerque’s conquest of the city and marriages between Portuguese outsiders and local women. 2 Revisiting the Creole Port City * I am very grateful to Alain Pascal Kaly, from Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, for having introduced me to Abdoulaye Sadji’s work and also for having extensively discussed with me over the years the history and nature of Senegambian societies as well as intellectual legacies in the region, 180 Notes in addition to the deep ties between Senegambia and the Antilles. -

Holding the World in Balance: the Connected Histories of the Iberian Overseas Empires, 1500–1640

Holding the World in Balance: The Connected Histories of the Iberian Overseas Empires, 1500–1640 SANJAY SUBRAHMANYAM America bores open all her mines, and unearths her silver and her treasure, to hand them over to our own Spain, which enjoys the world’s best in every measure, from Europe, Libya, Asia, by way of San Lu´car, and through Manila, despite the Chinaman’s displeasure. Bernardo de Balbuena, Grandeza mexicana (1604)1 THE EARLY MODERN WORLD WAS FOR THE MOST PART A PATCHWORK of competing and intertwined empires, punctuated by the odd interloper in the form of a nascent “na- tion-state.” At the time of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the real contours of the political map of the world were as follows: from east to west, a China that had just been conquered by the Qing, who would make an expansive push westward; then the vast Mughal Empire, from the hills of Burma to Afghanistan; the Ottoman Empire, whose writ still effectively ran from Basra to Central Europe and Morocco; the Rus- sian Empire, by then extending well into Siberia and parts of Central Asia; the lim- ited rump of the Holy Roman Empire in Central Europe; the burgeoning commercial empires of England and the Netherlands in both Asia and America; and, last but not least, the still-extensive spread of the great empires of Spain and Portugal.2 Other states could also make some claim to imperial status, including Munhumutapa in southeastern Africa, the Burma of the Toungoo Dynasty, and Safavid Iran. The cru- cial point, however, is not just that these empires existed, but that they recognized one another, and as a consequence they often borrowed symbols, ideas, and insti- tutions across recognizable boundaries.