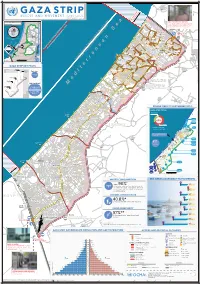

The Gaza Strip and Jericho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abuses Against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces WATCH

Occupied Palestinian Territories HUMAN No News is Good News RIGHTS Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces WATCH No News is Good News Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-759-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org April 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-759-0 No News is Good News Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 3 West Bank ....................................................................................................................... 5 Reports of Increased Harassment ............................................................................. 6 The Role of PA Security Forces ................................................................................... 7 Gaza ............................................................................................................................. -

Why the Walls of Jericho Came Tumbling Down

WHY THE WALLS OF JERICHO CAME TUMBLING DOWN SHUBERT SPERO What follows is an attempt to give a rational explanation for the fall of the walls of Jericho following the siege of the city by the Israelite forces led by 1 Joshua. The theory I wish to propose is designed not to replace the textual account but to complement it. That is, to suggest a reality that does not contradict the official version but which may have been behind it and for whose actual occurrence several hints may be found in the text. The fall of the walls of Jericho was indeed a wondrous event and the text properly sees God as the agent in the sense that it was He who inspired Joshua to come up 2 with his ingenious plan. Our theory suggests a connection between the two outstanding features of the story: (1) The adventure of the two Israelite spies in the house of Rahab the inn-keeper, before the Israelites crossed the Jordan, and (2) the mystify- ing circling of the city by the priestly procession for the seven days preceding the tumbling down of the walls. Let us first review the salient facts involved in the incident of the spies. We are told that Rahab's dwelling was part of the city wall and that in the wall she dwelt (Josh. 2:15) with a window that looked out on the area outside the city. The spies avoid capture by the Canaanite authorities through the efforts of Rahab and, in gratitude, they promise the woman that she and her family will not be harmed during the impending attack, and instruct her to gather them all into her house and hang scarlet threads in the window. -

The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

THE ORIGINS OF HAMAS: MILITANT LEGACY OR ISRAELI TOOL? JEAN-PIERRE FILIU Since its creation in 1987, Hamas has been at the forefront of armed resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the move- ment itself claims an unbroken militancy in Palestine dating back to 1935, others credit post-1967 maneuvers of Israeli Intelligence for its establishment. This article, in assessing these opposing nar- ratives and offering its own interpretation, delves into the historical foundations of Hamas starting with the establishment in 1946 of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (the mother organization) and ending with its emergence as a distinct entity at the outbreak of the !rst intifada. Particular emphasis is given to the Brotherhood’s pre-1987 record of militancy in the Strip, and on the complicated and intertwining relationship between the Brotherhood and Fatah. HAMAS,1 FOUNDED IN the Gaza Strip in December 1987, has been the sub- ject of numerous studies, articles, and analyses,2 particularly since its victory in the Palestinian legislative elections of January 2006 and its takeover of Gaza in June 2007. Yet despite this, little academic atten- tion has been paid to the historical foundations of the movement, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Gaza branch established in 1946. Meanwhile, two contradictory interpretations of the movement’s origins are in wide circulation. The !rst portrays Hamas as heir to a militant lineage, rigorously inde- pendent of all Arab regimes, including Egypt, and harking back to ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam,3 a Syrian cleric killed in 1935 while !ghting the British in Palestine. -

The Bible, the Qur'an and Science

مكتبةمكتبة مشكاةمشكاة السإلميةالسإلمية The Bible, The Qur'an and Science The Holy Scriptures Examined In The Light Of Modern Knowledge by Dr. Maurice Bucaille Translated from French by Alastair D. Pannell and The Author مكتبةمكتبة مشكاةمشكاة السإلميةالسإلمية Table of Contents Foreword.........................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................3 The Old Testament..........................................................................9 The Books of the Old Testament...................................................13 The Old Testament and Science Findings....................................23 Position Of Christian Authors With Regard To Scientific Error In The Biblical Texts...........................................................................33 Conclusions...................................................................................37 The Gospels..................................................................................38 Historical Reminder Judeo-Christian and Saint Paul....................41 The Four Gospels. Sources and History.......................................44 The Gospels and Modern Science. The General Genealogies of Jesus.........................................................................................62 Contradictions and Improbabilities in the Descriptions.................72 Conclusions...................................................................................80 -

The Working Group on the Status of Palestinian Women in Israel ______

The Working Group on the Status of Palestinian Women in Israel ____________________________________________________________ NGO Report: The Status of Palestinian Women Citizens of Israel Contents Page I. ‘The Working Group on the Status of Palestinian Women in Israel’..........................2 II. Forward - Rina Rosenberg...........................................................................................5 III. Palestinian Women in Israel - ‘Herstory’- Nabila Espanioly......................................8 IV. Political Participation, Public Life, and International Representation - Aida Toma Suliman & Nabila Espanioly..........................................................18 V. Education - Dr. Hala Espanioly Hazzan, Arabiya Mansour, & A’reen Usama Howari.................................................................................23 VI. Palestinian Women and Employment - Nabila Espanioly.........................................31 VII. Palestinian Women’s Health - Siham Badarne..........................................................45 VIII. Personal Status and Family Laws - Suhad Bishara, Advocate, & Aida Toma Suliman...........................................................................................56 IX. Violence Against Women - Iman Kandalaft & Hoda Rohana..................................63 X. Recommendations - All Members..............................................................................75 XI. Selected Bibliography................................................................................................83 -

Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014

Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014 Transport Services Logistics Cluster transportation into the Gaza Strip since activation on 30 July 2014: Total Number of Trucks 184 Total Number of Pallets 4809 Total number Organizations Supported 37 Logistics Cluster transportation into the Gaza Strip – 31 August 2014: Final Number Number of Consignor From Consignee Sector Destination of pallets Trucks Shelter Global Communities Ramallah Gaza City CHF International 30 1 Food Ministry Of Social Ministry Of Social Shelter Ramallah Gaza City 140 5 Affairs (MoSA) Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Agricultural Agricultural Food Development Development Ramallah Gaza City 52 Shelter 2 Association (PARC) Association (PARC) WASH Ramallah Gaza Union of Union of Agricultural Food Agricultural Work Work Committees Nablus Gaza City 31 Shelter 1 Committees (UAWC) WASH (UAWC) Food Hebron Food Trade Ministry Of Social Hebron Gaza City 56 Shelter 2 Association Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Food Social Welfare Ministry Of Social Bethlehem Gaza City 23 Shelter 1 Committee Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Private donation from Ministry Of Social Shelter Bethlehem Gaza City 14 Dar Salah Affairs (MoSA) Gaza Food Earth & Human Applied Research Center for Shelter Institute- Bethlehem Gaza City 2 1 researches and Food Jerusalem(ARIJ) studies (EHCRS) Social Welfare Ministry Of Social Shelter Bethlehem Gaza City 10 Committee Affairs (MoSA) Gaza Food TOTAL 358 13 Coordination/ Information Management/ GIS The Logistics Cluster is compiling information and assessing partners’ needs to determine whether the Rafah crossing can be used on a more permanent basis to support the humanitarian community transport relief items from Egypt into the Gaza Strip. www.logcluster.org Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014 Logistics Gaps and Bottlenecks The Logistics Cluster continues to monitor the impact of the ceasefire on logistics access constraints and the security of humanitarian space for the transportation and distribution of relief supplies. -

Palestine - Walking Through History

Palestine - Walking through History April 04 - 08, 2019 Cultural Touring | Hiking | Cycling | Jeep touring Masar Ibrahim Al-Khalil is Palestine’s long distance cultural walking route. Extending 330 km from the village of Rummana in the northwest of Jenin to Beit Mirsim southwest of Al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (Ibrahimi Mosque) in Hebron. The route passes through more than fifty cities and villages where travelers can experience the legendary Palestinian hospitality. Beginning with a tour of the major sites in Jerusalem, we are immediately immersed in the complex history of the region. Over the five days, we experience sections of this route, hiking and biking from the green hills of the northern West Bank passing through the desert south of Jericho to Bethlehem. Actively traveling through the varied landscapes, biodiverse areas, archaeological remains, religious sites, and modern day lively villages, we experience rich Palestinian culture and heritage. Palestinians, like their neighboring Arabs, are known for their welcoming warmth and friendliness, important values associated with Abraham (Ibrahim). There is plenty of opportunity to have valuable encounters with local communities who share the generosity of their ancestors along the way, often over a meal of delicious Palestinian cuisine. The food boasts a range of vibrant and flavorsome dishes, sharing culinary traits with Middle Eastern and East Mediterranean regions. Highlights: ● Experience Palestine from a different perspective – insights that go beyond the usual headlines ● Hike and bike through beautiful landscapes ● Witness history in Jerusalem, Sebastiya, Jericho, Bethlehem ● Map of the route ITINERARY Day 1 – 04 April 2019 - Thursday : Our trip begins today with a 8:00am pick-up at the hotel in Aqaba, the location on AdventureNEXT Near East. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain National Affairs J_ HE YEAR 1986 WAS marked by sharply contrasting trends in political and economic affairs. Notable improvement took place in labor-industrial relations, with the total of working days lost through strikes the lowest in over 20 years. By contrast, the total of 3.2 million unemployed—about 11 percent of the working population—represented only a slight decline over the previous year. Politically, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government made a remarkable late-year recovery, following some early disasters. The year began with two cabinet resignations, first that of Defense Secretary Michael Heseltine, soon after that of Secretary of Trade and Industry Leon Brittan. The two ministers had clashed over conflicting plans for saving the ailing Westland helicopter company. Following this controversy, the government retreated, in the face of opposition on patriotic grounds, on plans to sell Leyland Trucks to the General Motors Corpora- tion and Leyland Cars to the Ford Motor Company. Another threat to the govern- ment was the drop in the price of North Sea oil from $20 a barrel in January to $10 in the summer, although it recovered to $15 by the end of the year. Early in the year, public-opinion polls showed the Conservatives having 33 per- cent support, compared to Labor's 38 percent, and the Social Democratic/Liberal Alliance's 28 percent. By the end of the year the respective percentages were 41, 39, and 18. Although several Tory victories in local elections in September and October appeared to signal an upward trend, the recovery was perhaps due less to the Conservative party's achievements than to opposition to the defense policies of Labor and the Social Democratic/Liberal Alliance. -

State of Palestine Humanitarian Situation Report

State of Palestine Humanitarian Situation Report Gaza Strip State of Palestine January – June 2018 water in her home ©UNICEF/ ©UNICEF/ waterSOP/ her in home Eyad El Baba running A her from girl hands is washing Highlights • Since the start of the demonstrations associated with the “Great March of Return” on 1,300,000 # of children affected out of total 2.5m 30th March, 135 people have been killed, including 17 children in Gaza. More than people in need (UN OCHA Humanitarian HRP 15,501 people were injured, 8,221 (53%) of them hospitalized. According to MoH, 2,947 2018) children were injured, comprising 19% of total injures as of 30 June, 2018. • The current deterioration of the situation in Gaza and rising tensions in the West Bank 2,500,000 trigger urgent funding needs for child protection, health, WASH and education # of people in need (UN OCHA Humanitarian HRP 2018) interventions to address the growing humanitarian needs. Only US$ 9.1 million or 36 per cent of the initial requirements was available as of 30 June, 2018. 652,000 • A total of 718 injured children have been supported by Child Protection/Mental Health # of children to be reached and Psychosocial Services (MHPSS) working group members through home visits, and (UNICEF Humanitarian Action for Children 2018) Psychological First Aid; children in need of more specialized care were referred to case management, utilizing the child protection referral pathways. This includes those who 729,000 # of people to be reached have parents, siblings, relatives or friends injured or killed during demonstrations. (UNICEF Humanitarian Action for Children 2018) • Prepositioned essential drugs and medical consumables were released to cover emergency medical care for 111,532 children and their families. -

The Palestinian People

The Palestinian People The Palestinian People ❖ A HISTORY Baruch Kimmerling Joel S. Migdal HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2003 Copyright © 1994, 2003 by Baruch Kimmerling and Joel S. Migdal All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America An earlier version of this book was published in 1994 as Palestinians: The Making of a People Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0-674-01131-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-01129-5 (paper) To the Palestinians and Israelis working and hoping for a mutually acceptable, negotiated settlement to their century-long conflict CONTENTS Maps ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xxi Note on Transliteration xxiii Introduction xxv Part One FROM REVOLT TO REVOLT: THE ENCOUNTER WITH THE EUROPEAN WORLD AND ZIONISM 1. The Revolt of 1834 and the Making of Modern Palestine 3 2. The City: Between Nablus and Jaffa 38 3. Jerusalem: Notables and Nationalism 67 4. The Arab Revolt, 1936–1939 102 vii Contents Part Two DISPERSAL 5. The Meaning of Disaster 135 Part Three RECONSTITUTING THE PALESTINIAN NATION 6. Odd Man Out: Arabs in Israel 169 7. Dispersal, 1948–1967 214 8. The Feday: Rebirth and Resistance 240 9. Steering a Path under Occupation 274 Part Four ABORTIVE RECONCILIATION 10. The Oslo Process: What Went Right? 315 11. The Oslo Process: What Went Wrong? 355 Conclusion 398 Chronological List of Major Events 419 Notes 457 Index 547 viii MAPS 1. Palestine under Ottoman Rule 39 2. Two Partitions of Palestine (1921, 1949) 148 3. United Nations Recommendation for Two-States Solution in Palestine (1947) 149 4. -

Star Mountain Rehabilitation Center – Moravian Church December 2016

Star Mountain Rehabilitation Center – Moravian Church December 2016 A Year in Review QUARTER 4, 2016 21.12.2016 Vocational Training Program INTRODUCTION This is the first newsletter for Star Mountain Rehabilitation Center -Moravian Church, which It provides rehabilitation, training and employment will be issued on a quarterly basis starting in 2017 with the aim of connecting to our friends, brothers and sisters, everywhere. This issue is an exception, since it provides a year’s review of opportunities to 41 persons with intellectual disability from the 2016 as a whole. age of 14 years until 40 years old. They are trained on different vocational skills including agricultural work, olive soap and candle production, paper-recycling, assembly of electric Brief Background… outlets, embroidery stitches, sewing and housekeeping. Star Mountain (SMRC) is an institution of the Worldwide Moravian Church working in Palestine. It contributes in securing a life in dignity for persons with intellectual disability, Connecting trainees to companies and workshops in the through the provision of rehabilitation and training, integration and inclusion, awareness community is a main end goal. building and community mobilization, on the basis of love, dignity, justice and equality. 10.12.2016 SMRC is located in a village called Abu Qash, in Ramallah and Al-Bireh District, West Bank, Palestine, 25 km to the north of Jerusalem. SMRC trains and rehabilitates around 192 persons with intellectual disability of all ages inside and outside the center. Thirty-five qualified staff members work with great commitment and pride in this special mission. Here is a short description of each of our four rehabilitation programs: The Inclusive Kindergarten It provides rehabilitation and educational programs to children with intellectual disability from the age of 3 months until 6 years old for children who have disability, and until 4 years old for Community Work Program children without disability.