Phylogenetic Analysis of the Calvaria of Homo Floresiensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cave Radon Exposure, Dose, Dynamics and Mitigation

Chris L. Waring, Stuart I. Hankin, Stephen B. Solomon, Stephen Long, Andrew Yule, Robert Blackley, Sylvester Werczynski, and Andrew C. Baker. Cave radon exposure, dose, dynamics and mitigation. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 83, no. 1, p. 1-19. DOI:10.4311/2019ES0124 CAVE RADON EXPOSURE, DOSE, DYNAMICS AND MITIGATION Chris L. Waring1, C, Stuart I. Hankin1, Stephen B. Solomon2, Stephen Long2, Andrew Yule2, Robert Blackley1, Sylvester Werczynski1, and Andrew C. Baker3 Abstract Many caves around the world have very high concentrations of naturally occurring 222Rn that may vary dramatically with seasonal and diurnal patterns. For most caves with a variable seasonal or diurnal pattern, 222Rn concentration is driven by bi-directional convective ventilation, which responds to external temperature contrast with cave temperature. Cavers and cave workers exposed to high 222Rn have an increased risk of contracting lung cancer. The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) has re-evaluated its estimates of lung cancer risk from inhalation of radon progeny (ICRP 115) and for cave workers the risk may now (ICRP 137) be 4–6 times higher than previously recognized. Cave Guides working underground in caves with annual average 222Rn activity 1,000 Bq m3 and default ICRP assumptions (2,000 workplace hours per year, equilibrium factor F 0.4, dose conversion factor DCF 14 µSv 3 1 1 d13 (kBq h m ) could now receive a dose of 20 mSv y . Using multiple gas tracers ( C CO2, Rn and N2O), linked weather, source gas flux chambers, and convective air flow measurements a previous study unequivocally identified the external soil above Chifley Cave as the source of cave222 Rn. -

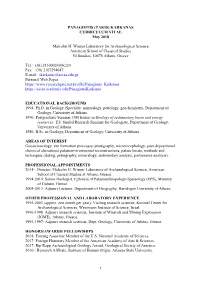

CV Karkanas 2018.Pdf

PANAGIOTIS (TAKIS) KARKANAS CURRICULUM VITAE May 2018 Malcolm H. Wiener Laboratory for Archaeological Science American School of Classical Studies 54 Soudias, 10676 Athens, Greece Tel.: (30) 2130002400x224 Fax: (30) 2107294047 E-mail: [email protected] Personal Web Pages: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Panagiotis_Karkanas https://ascsa.academia.edu/PanagiotisKarkanas EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND 1994: Ph.D. in Geology (Specialty: mineralogy, petrology, geochemistry), Department of Geology, University of Athens. 1990: Postgraduate Seminar (300 hours) in Geology of sedimentary basin and energy resources. EU funded Research Seminar for Geologists, Department of Geology, University of Athens. 1986: B.Sc. in Geology, Department of Geology, University of Athens. AREAS OF INTEREST Geoarchaeology: site formation processes (stratigraphy, micromorphology, post-depositional chemical alterations) palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, paleoclimate, methods and techniques (dating, petrography, mineralogy, sedimentary analysis, provenance analysis). PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2014-: Director, Malcolm H. Wiener Laboratory of Archaeological Science, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece. 1994-2014: Senior Geologist, Ephoreia of Palaeoanthropology-Speleology (EPS), Ministry of Culture, Greece. 2004-2013: Adjunct Lecturer, Department of Geography, Harokopio University of Athens. OTHER PROFESSIONAL AND LABORATORY EXPERIENCE 1995-2003 (approx. one month per year): Visiting research scientist, Kimmel Center for Archaeological Sciences, -

13.10 News 934-935

NEWS NATURE|Vol 437|13 October 2005 Forbidden cave: without permits, the discoverers of the hobbit are unable to continue digging at Liang Bua cave. C. TURNEY, UNIV. WOLLONGONG UNIV. TURNEY, C. More evidence for hobbit unearthed as diggers are refused access to cave Even as researchers uncover more details The study of the bones that have so far been about the ancient ‘hobbit’ people of Indonesia, recovered has already been hindered, the they fear that they may never return to Liang researchers complain. Last winter, after hold- Bua cave, where the crucial specimens were ing the remains for about four months, Jacob found in 2003. returned them to the discovery team with “My guess is that we will not work at Liang some bones broken or shattered. The bones Bua again, this year or any other year,” says may have been damaged when casts were team leader Michael Morwood, an archaeolo- attempted or during transport. Today’s article C. TURNEY, UNIV. WOLLONGONG UNIV. TURNEY, C. gist at the University of New England in was delayed by at least six months, the authors Armidale. say, because the bones were not available The latest findings from the cave reveal, for follow-up studies. The newly described among other details, that the metre-tall jaw, for instance, was broken in half between humans, known as Homo floresiensis, lived on the front teeth, and the break has obliterated the island of Flores as little as 12,000 years ago certain key structures. (see page 1012). But continued exploration at “It’s an outrage,” says team anthropologist Liang Bua is being blocked, the researchers say, Peter Brown, also based at the University of because the discovery of miniature humans New England. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

The Carnivore Remains from the Sima De Los Huesos Middle Pleistocene Site

N. Garcia & The carnivore remains from the Sima de J. L. Arsuaga los Huesos Middle Pleistocene site Departamento de Paleontologia, (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain) Facultad de Ciencias Geologicas, U.A. de Paleoantropologia & Instituto de View metadata, citation and similar papersRemain ats ocore.ac.ukf carnivores from the Sima de los Huesos sitebrought representin to you gby a t COREleast Geologia Economica, Universidad 158 adult individuals of a primitive (i.e., not very speleoid) form of Ursus Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad provided by Servicio de Coordinación de Bibliotecas de la... deningeri Von Reichenau 1906, have been recovered through the 1995 field Universitaria, 28040 Madrid, Spain season. These new finds extend our knowledge of this group in the Sierra de Atapuerca Middle Pleistocene. Material previously classified as Cuoninae T. Torres indet. is now assigned to Canis lupus and a third metatarsal assigned in 1987 to Departamento de Ingenieria Geoldgica, Panthera cf. gombaszoegensis, is in our opinion only attributable to Panthera sp. The Escuela Tecnica Superior de Ingenieros family Mustelidae is added to the faunal list and includes Maites sp. and a de Minas, Universidad Politecnica smaller species. The presence of Panthera leo cf. fossilis, Lynxpardina spelaea and de Madrid, Rios Rosas 21, Fells silvestris, is confirmed. The presence of a not very speloid Ursus deningeri, 28003 Madrid, Spain together with the rest of the carnivore assemblage, points to a not very late Middle Pleistocene age, i.e., oxygen isotope stage 7 or older. Relative frequencies of skeletal elements for the bear and fox samples are without major biases. The age structure of the bear sample, based on dental wear stages, does not follow the typical hibernation mortality profile and resembles a cata strophic profile. -

Test 3 Study Guide

Test 3 Study Guide ANATOMICALLY MODERN HUMANS- earliest fossils found in Africa dated to about 200,000 years ago, well-rounded rear of skull (no occipital bun), high skull (doesn’t slope), small brow ridges (supra orbital torus), noticeable chin, associated with Upper Paleolithic tools (some had blades and some were made of bone), created shelters and they were the first to create artistic objects (note cave drawings possible sympathetic magic-related to the desire to capture more animals). Omo- oldest known AMH found at Omo site in Ethiopia—date ~ 195,000ya. Same morphology as noted above. homo heidelbergensis- a species of archaic human w/ a brain size close to that of modern humans (~1500-1800cc’s or more) but had a larger face and lived in Africa, Europe and Asia between 800,000 and 200,000 ya. Cro-Magnon Man- found in Cro-Magnon, France…dates between 27,000-23,000ya, earliest AMH populations found in Europe, very sophisticated, fished, cured ailments, made clothing and jewelry, built rafts etc… complication: Homo Floresiensis “hobbit” Discovered in Liang Bua cave on the island of Flores in Indonesia, 3.5”, 417cc’s found w/ tools and bones, dates between 12,000 and 94,000 ya, possible dwarf species, AMH characteristics. Possible explanations= island dwarfism, microcephalic, pathology, different species= unsure of where it falls on our phylogenic tree PREHISTORIC ART (note Lascaux cave, France) >600 pictures of animals, mostly horses don’t know purpose possible sympathetic magic cultural symbolism? means of communication ideas? pictograph- painting on surface like a cave wall petroglyph- design carved into rock or other surface HUMAN ORIGINS Associated models: (from book as per your syllabus) multiregional model- evolution happened 1.8 mya in Africa from a single lineage but that changes in modern human anatomy happened by way of gene flow as archaic humans moved across the Old World. -

Isotopic Analysis of the Ecology of Herbivores and Carnivores from the Middle Pleistocene Deposits of the Sierra De Atapuerca, Northern Spain N

Isotopic analysis of the ecology of herbivores and carnivores from the Middle Pleistocene deposits of the Sierra De Atapuerca, northern Spain N. Garcia Gar~ia~,~,",R.S. FeranecC.*, J.L. ~rsua~a~,~,J.M. BermGdez de Castrod, E. Carbonelle 'Deportomento de Poleontologio, Focultod de Ciencior Geoldgicor, Univerridod Complutense de Modrid, Ciudod Univerritorio, 28040 Modrid, Spoin Centlo Mkt0 (UCM-ISUII) de Evolucidn y Comportomiento Humonor, CfSinerio Delgodo 4, Pob. 14, 29029 Modrid, Spoin 'New York Stote Museum. 3140 Culturol Education Center. Albonv. NY 12230. USA *centre Nocionol de Invertigoci6n robre 10 Evoluci6n Humono -?M, Avda de ia Pog 28, 09004 Burger, Spoin eInstitut Cotold de Poleoecologio Humono i Evoluci6 Sociol (IPHES), C/ Erconodor, r/n 43003 Torrogono, Spoin ABSTRACT Carbon and oxygen isotope values reveal resource partitioning among the large mammal fauna from three contemporaneous Middle Pleistocene hominid-bearing localities within the Sierra de Atapuerca (northern Spain). Carbon isotope values sampled from the tooth enamel of fauna present during Ata- ouerca Faunal Unit 6 show that a C?-dominated ecosvstem surrounded the area where fossils were preserved during this time. For the herbivores, Fallow deer isotope values are significantly different from Red deer and horses and show that this species did not forage in open environments at this locality. Red Keywords: deer and horses show similar feedine strateeies with less neeative carbon values imolvine use of more C-l3 Diet Ecology Enamel that this species is herbivorous. Special metabolic mechanisms involved in hibernation in U deningeri Mammal might also have influenced its isotope values. The carbon isotope values of remaining carnivores were 0-18 similar and suggest that each was typically a generalist carnivore, eating a wide variety of prey items. -

Pleistocene Cave Hyenas in the Iberian Peninsula: New Insights from Los Aprendices Cave (Moncayo, Zaragoza)

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Pleistocene cave hyenas in the Iberian Peninsula: New insights from Los Aprendices cave (Moncayo, Zaragoza) Víctor Sauqué, Raquel Rabal-Garcés, Joan Madurell-Malaperia, Mario Gisbert, Samuel Zamora, Trinidad de Torres, José Eugenio Ortiz, and Gloria Cuenca-Bescós ABSTRACT A new Pleistocene paleontological site, Los Aprendices, located in the northwest- ern part of the Iberian Peninsula in the area of the Moncayo (Zaragoza) is presented. The layer with fossil remains has been dated by amino acid racemization to 143.8 ± 38.9 ka (earliest Late Pleistocene or latest Middle Pleistocene). Five mammal species have been identified in the assemblage: Crocuta spelaea (Goldfuss, 1823) Capra pyre- naica (Schinz, 1838), Lagomorpha indet, Arvicolidae indet and Galemys pyrenaicus (Geoffroy, 1811). The remains of C. spelaea represent a mostly complete skeleton in anatomical semi-connection. The hyena specimen represents the most complete skel- eton ever recovered in Iberia and one of the most complete remains in Europe. It has been compared anatomically and biometrically with both European cave hyenas and extant spotted hyenas. In addition, a taphonomic study has been carried out in order to understand the origin and preservation of these exceptional remains. The results sug- gest rapid burial with few scavenging modifications putatively produced by a medium sized carnivore. A review of the Pleistocene Iberian record of Crocuta spp. has been carried out, enabling us to establish one of the earliest records of C. spelaea in the recently discovered Los Aprendices cave, and also showing that the most extensive geographical distribution of this species occurred during the Late Pleistocene (MIS4- 2). -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Calvaria of Homo Floresiensis Valéry Zeitoun, Véronique Barriel, Harry Widianto

Phylogenetic analysis of the calvaria of Homo floresiensis Valéry Zeitoun, Véronique Barriel, Harry Widianto To cite this version: Valéry Zeitoun, Véronique Barriel, Harry Widianto. Phylogenetic analysis of the calvaria of Homo floresiensis. Comptes Rendus Palevol, Elsevier Masson, 2016, 10.1016/j.crpv.2015.12.002. hal-01290521 HAL Id: hal-01290521 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01290521 Submitted on 18 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License G Model PALEVO-924; No. of Pages 14 ARTICLE IN PRESS C. R. Palevol xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Comptes Rendus Palevol w ww.sciencedirect.com Human palaeontology and prehistory Phylogenetic analysis of the calvaria of Homo floresiensis Analyse phylogénétique de la calvaria de Homo floresiensis a,∗ b c Valéry Zeitoun , Véronique Barriel , Harry Widianto a UMR 7207 CNRS–MNHN–Université Paris-6, Sorbonne universités, Centre de recherche sur la paléobiodiversité et les e paléoenvironnements, Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie, T. 46-56, 5 étage, case 104, 4, place Jussieu, 75252 Paris cedex 05, France b UMR 7207 CNRS–MNHN–Université Paris-6, Sorbonne universités, Centre de recherche sur la paléobiodiversité et les paléoenvironnements, 8, rue Buffon, 75252 Paris cedex 05, France c Directorate of Cultural properties and Museums, Komplek Kemdikbud, Gedung E Lt. -

Proceedings VOLUME 1

16th INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF SPELEOLOGY Proceedings VOLUME 1 Edited by Michal Filippi Pavel Bosák 16th INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF SPELEOLOGY Czech Republic, Brno July 21 –28, 2013 Proceedings VOLUME 1 Edited by Michal Filippi Pavel Bosák 2013 16th INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF SPELEOLOGY Czech Republic, Brno July 21 –28, 2013 Proceedings VOLUME 1 Produced by the Organizing Committee of the 16th International Congress of Speleology. Published by the Czech Speleological Society and the SPELEO2013 and in the co-operation with the International Union of Speleology. Design by M. Filippi and SAVIO, s.r.o. Layout by SAVIO, s.r.o. Printed in the Czech Republic by H.R.G. spol. s r.o. The contributions were not corrected from language point of view. Contributions express author(s) opinion. Recommended form of citation for this volume: Filippi M., Bosák P. (Eds), 2013. Proceedings of the 16th International Congress of Speleology, July 21–28, Brno. Volume 1, p. 453. Czech Speleological Society. Praha. ISBN 978-80-87857-07-6 KATALOGIZACE V KNIZE - NÁRODNÍ KNIHOVNA ČR © 2013 Czech Speleological Society, Praha, Czech Republic. International Congress of Speleology (16. : Brno, Česko) 16th International Congress of Speleology : Czech Republic, Individual authors retain their copyrights. All rights reserved. Brno July 21–28,2013 : proceedings. Volume 1 / edited by Michal Filippi, Pavel Bosák. -- [Prague] : Czech Speleological Society and No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any the SPELEO2013 and in the co-operation with the International form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including Union of Speleology, 2013 photocopying, recording, or any data storage or retrieval ISBN 978-80-87857-07-6 (brož.) system without the express written permission of the 551.44 * 551.435.8 * 902.035 * 551.44:592/599 * 502.171:574.4/.5 copyright owner. -

Craniofacial Morphology of Homo Floresiensis: Description, Taxonomic

Journal of Human Evolution 61 (2011) 644e682 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Craniofacial morphology of Homo floresiensis: Description, taxonomic affinities, and evolutionary implication Yousuke Kaifu a,b,*, Hisao Baba a, Thomas Sutikna c, Michael J. Morwood d, Daisuke Kubo b, E. Wahyu Saptomo c, Jatmiko c, Rokhus Due Awe c, Tony Djubiantono c a Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4-1-1 Amakubo, Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki Prefecture Japan b Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 3-1-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan c National Research and Development Centre for Archaeology, Jl. Raya Condet Pejaten No 4, Jakarta 12001, Indonesia d Centre for Archaeological Science, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia article info abstract Article history: This paper describes in detail the external morphology of LB1/1, the nearly complete and only known Received 5 October 2010 cranium of Homo floresiensis. Comparisons were made with a large sample of early groups of the genus Accepted 21 August 2011 Homo to assess primitive, derived, and unique craniofacial traits of LB1 and discuss its evolution. Prin- cipal cranial shape differences between H. floresiensis and Homo sapiens are also explored metrically. Keywords: The LB1 specimen exhibits a marked reductive trend in its facial skeleton, which is comparable to the LB1/1 H. sapiens condition and is probably associated with reduced masticatory stresses. However, LB1 is Homo erectus craniometrically different from H. sapiens showing an extremely small overall cranial size, and the Homo habilis Cranium combination of a primitive low and anteriorly narrow vault shape, a relatively prognathic face, a rounded Face oval foramen that is greatly separated anteriorly from the carotid canal/jugular foramen, and a unique, tall orbital shape. -

A Multi-Method Approach for Speleogenetic Research on Alpine Karst Caves

GEOMOR-05115; No of Pages 20 Geomorphology xxx (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph A multi-method approach for speleogenetic research on alpine karst caves. Torca La Texa shaft, Picos de Europa (Spain) Daniel Ballesteros a,⁎, Montserrat Jiménez-Sánchez a, Santiago Giralt b, Joaquín García-Sansegundo a, Mónica Meléndez-Asensio c a Department of Geology, University of Oviedo, c/Jesús Arias de Velasco s/n, 33005, Spain b Institute of Earth Sciences Jaume Almera (ICTJA, CSIC), c/Lluís Solé i Sabarís s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain c Geological Survey of Spain (IGME), c/Matemático Pedrayes 25, 33005 Oviedo, Spain article info abstract Article history: Speleogenetic research on alpine caves has advanced significantly during the last decades. These investigations Received 30 January 2014 require techniques from different geoscience disciplines that must be adapted to the methodological constraints Received in revised form 23 February 2015 of working in deep caves. The Picos de Europa mountains are one of the most important alpine karsts, including Accepted 24 February 2015 14% of the World's Deepest Caves (caves with more than 1 km depth). A speleogenetic research is currently being Available online xxxx developed in selected caves in these mountains; one of them, named Torca La Texa shaft, is the main goal of this article. For this purpose, we have proposed both an optimized multi-method approach for speleogenetic research Keywords: Cave level in alpine caves, and a speleogenetic model of the Torca La Texa shaft. The methodology includes: cave surveying, 234 230 Karst massif dye-tracing, cave geometry analyses, cave geomorphological mapping, Uranium series dating ( U/ Th) and Shaft geomorphological, structural and stratigraphical studies of the cave surroundings.