The Internal Cranial Anatomy of the Middle Pleistocene Broken Hill 1 Cranium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Evolutionary Calendar - Evolution in a Year)I------1 January • December F------{( March ) ( June September

The Human Evolutionary Calendar - Evolution in a Year)I---------1 January • December f-------{( March ) ( June September SahelanthropusTchadensi Australopithecus sediba Homo rh odes iensis Ardipithecus ramidus 7,000,000 - 6,000,000 yrs. 2,000,000 - , ,750,000 yrs. 300,000 -125,000 yrs. 3,200,000 • 4,300,000 yrs. Homo rudolfensis Orrorin tugenensis 1,900,000 - 1.750,000 yrs. Homo pekin ensi s 6, 100,000 - 5,BOO,Oci:l yrs. 700,000 - 500,000 yrs. Australopit ec us anamensis 4,200,00 - 3,900,000 yrs. Ardipithecus kadabba 5,750,000 - 5,200,000 yrs. Ho m o Ergaster 1,900,000 - 1,3,000,000 yrs. Homo heidelberge nsis 700,000 • 200,000 yrs. Australopithecus afarensis Homo erectus 3,900,000 - 2,900,000 yrs. 1,800,000 • 250,000 yrs. Ho mo antecessor Australopithecus africa nus Ho mo habilis 1,000,000 -700,000 yrs. 3,800,000 - 3,000,000 yrs. 2,350,000 - 1,450,000 yrs. Ho m o g eorgicus Kenya nthropus platyo ps 1,800,000- 1.3000,000 yrs. 3,500,000 - 3,200,000 yrs. Ho m o nea nderthalensis 200,000 · 28,000 yrs. Paranthropus bo ise i Paranthropus aethiopicu 2,275,000- 1,250,000 yrs. De nisova ho minins 2,650,000 - 2,300,000 yrs. 200,000 - 30,000 yrs. Paranthropus robustus/crass iden s Australopithecus garhi 1,750,000- 1,200,000 yrs. 2,750,000 - 2.400,000 yrs. Red Deer Cave Peo ple ?- 11,000yrs. Ho mo sa piens sapien s 200~ Ho m o fl o res iensis 100,000 • 13,000 yrs. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

The Human Cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia

G. Philip Rightmire The human cranium from Bodo, Department of Anthropology, State Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the University of New York, Binghamton, New York 13902-6000, U.S.A. Middle Pleistocene? Received 19 June 1995 The cranium found at Bodo in 1976 is derived from Middle Pleistocene Revision received 13 December deposits containing faunal remains and Acheulean artefacts. A parietal 1995 recovered later must belong to a second individual, probably representing the and accepted 30 December 1995 same taxon. The cranium includes the face, much of the frontal bone, parts of the midvault and the base anterior to the foramen magnum. It is clear that the Keywords: human evolution, Bodo hominids resemble Homo erectus in a number of characters. The facial craniofacial morphology, species, skeleton is large, especially in its breadth dimensions. The braincase is low and Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, decidedly archaic in overall appearance. Individual bones are quite thick. ‘‘archaic’’ Homo sapiens. Behind the projecting supraorbital torus, the frontal profile is flattened. The midline keel and bregmatic eminence are characteristic of H. erectus. Frontal narrowing is less pronounced than in crania from Olduvai and Koobi Fora but slightly greater than in some Sangiran specimens. The parietal displays a prominent angular torus. Whether the inferior part of the tympanic plate was substantially thickened cannot be checked, but in the placement of its petrous bone and the resulting crevice-like configuration of the foramen lacerum, the Bodo hominid resembles H. erectus. Other traits seem more clearly to be synapomorphies uniting Bodo with later Middle Pleistocene populations and recent humans. -

Cave Radon Exposure, Dose, Dynamics and Mitigation

Chris L. Waring, Stuart I. Hankin, Stephen B. Solomon, Stephen Long, Andrew Yule, Robert Blackley, Sylvester Werczynski, and Andrew C. Baker. Cave radon exposure, dose, dynamics and mitigation. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 83, no. 1, p. 1-19. DOI:10.4311/2019ES0124 CAVE RADON EXPOSURE, DOSE, DYNAMICS AND MITIGATION Chris L. Waring1, C, Stuart I. Hankin1, Stephen B. Solomon2, Stephen Long2, Andrew Yule2, Robert Blackley1, Sylvester Werczynski1, and Andrew C. Baker3 Abstract Many caves around the world have very high concentrations of naturally occurring 222Rn that may vary dramatically with seasonal and diurnal patterns. For most caves with a variable seasonal or diurnal pattern, 222Rn concentration is driven by bi-directional convective ventilation, which responds to external temperature contrast with cave temperature. Cavers and cave workers exposed to high 222Rn have an increased risk of contracting lung cancer. The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) has re-evaluated its estimates of lung cancer risk from inhalation of radon progeny (ICRP 115) and for cave workers the risk may now (ICRP 137) be 4–6 times higher than previously recognized. Cave Guides working underground in caves with annual average 222Rn activity 1,000 Bq m3 and default ICRP assumptions (2,000 workplace hours per year, equilibrium factor F 0.4, dose conversion factor DCF 14 µSv 3 1 1 d13 (kBq h m ) could now receive a dose of 20 mSv y . Using multiple gas tracers ( C CO2, Rn and N2O), linked weather, source gas flux chambers, and convective air flow measurements a previous study unequivocally identified the external soil above Chifley Cave as the source of cave222 Rn. -

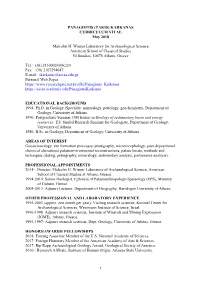

CV Karkanas 2018.Pdf

PANAGIOTIS (TAKIS) KARKANAS CURRICULUM VITAE May 2018 Malcolm H. Wiener Laboratory for Archaeological Science American School of Classical Studies 54 Soudias, 10676 Athens, Greece Tel.: (30) 2130002400x224 Fax: (30) 2107294047 E-mail: [email protected] Personal Web Pages: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Panagiotis_Karkanas https://ascsa.academia.edu/PanagiotisKarkanas EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND 1994: Ph.D. in Geology (Specialty: mineralogy, petrology, geochemistry), Department of Geology, University of Athens. 1990: Postgraduate Seminar (300 hours) in Geology of sedimentary basin and energy resources. EU funded Research Seminar for Geologists, Department of Geology, University of Athens. 1986: B.Sc. in Geology, Department of Geology, University of Athens. AREAS OF INTEREST Geoarchaeology: site formation processes (stratigraphy, micromorphology, post-depositional chemical alterations) palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, paleoclimate, methods and techniques (dating, petrography, mineralogy, sedimentary analysis, provenance analysis). PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2014-: Director, Malcolm H. Wiener Laboratory of Archaeological Science, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece. 1994-2014: Senior Geologist, Ephoreia of Palaeoanthropology-Speleology (EPS), Ministry of Culture, Greece. 2004-2013: Adjunct Lecturer, Department of Geography, Harokopio University of Athens. OTHER PROFESSIONAL AND LABORATORY EXPERIENCE 1995-2003 (approx. one month per year): Visiting research scientist, Kimmel Center for Archaeological Sciences, -

13.10 News 934-935

NEWS NATURE|Vol 437|13 October 2005 Forbidden cave: without permits, the discoverers of the hobbit are unable to continue digging at Liang Bua cave. C. TURNEY, UNIV. WOLLONGONG UNIV. TURNEY, C. More evidence for hobbit unearthed as diggers are refused access to cave Even as researchers uncover more details The study of the bones that have so far been about the ancient ‘hobbit’ people of Indonesia, recovered has already been hindered, the they fear that they may never return to Liang researchers complain. Last winter, after hold- Bua cave, where the crucial specimens were ing the remains for about four months, Jacob found in 2003. returned them to the discovery team with “My guess is that we will not work at Liang some bones broken or shattered. The bones Bua again, this year or any other year,” says may have been damaged when casts were team leader Michael Morwood, an archaeolo- attempted or during transport. Today’s article C. TURNEY, UNIV. WOLLONGONG UNIV. TURNEY, C. gist at the University of New England in was delayed by at least six months, the authors Armidale. say, because the bones were not available The latest findings from the cave reveal, for follow-up studies. The newly described among other details, that the metre-tall jaw, for instance, was broken in half between humans, known as Homo floresiensis, lived on the front teeth, and the break has obliterated the island of Flores as little as 12,000 years ago certain key structures. (see page 1012). But continued exploration at “It’s an outrage,” says team anthropologist Liang Bua is being blocked, the researchers say, Peter Brown, also based at the University of because the discovery of miniature humans New England. -

Taxonomic Tapestries the Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

The Carnivore Remains from the Sima De Los Huesos Middle Pleistocene Site

N. Garcia & The carnivore remains from the Sima de J. L. Arsuaga los Huesos Middle Pleistocene site Departamento de Paleontologia, (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain) Facultad de Ciencias Geologicas, U.A. de Paleoantropologia & Instituto de View metadata, citation and similar papersRemain ats ocore.ac.ukf carnivores from the Sima de los Huesos sitebrought representin to you gby a t COREleast Geologia Economica, Universidad 158 adult individuals of a primitive (i.e., not very speleoid) form of Ursus Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad provided by Servicio de Coordinación de Bibliotecas de la... deningeri Von Reichenau 1906, have been recovered through the 1995 field Universitaria, 28040 Madrid, Spain season. These new finds extend our knowledge of this group in the Sierra de Atapuerca Middle Pleistocene. Material previously classified as Cuoninae T. Torres indet. is now assigned to Canis lupus and a third metatarsal assigned in 1987 to Departamento de Ingenieria Geoldgica, Panthera cf. gombaszoegensis, is in our opinion only attributable to Panthera sp. The Escuela Tecnica Superior de Ingenieros family Mustelidae is added to the faunal list and includes Maites sp. and a de Minas, Universidad Politecnica smaller species. The presence of Panthera leo cf. fossilis, Lynxpardina spelaea and de Madrid, Rios Rosas 21, Fells silvestris, is confirmed. The presence of a not very speloid Ursus deningeri, 28003 Madrid, Spain together with the rest of the carnivore assemblage, points to a not very late Middle Pleistocene age, i.e., oxygen isotope stage 7 or older. Relative frequencies of skeletal elements for the bear and fox samples are without major biases. The age structure of the bear sample, based on dental wear stages, does not follow the typical hibernation mortality profile and resembles a cata strophic profile. -

Test 3 Study Guide

Test 3 Study Guide ANATOMICALLY MODERN HUMANS- earliest fossils found in Africa dated to about 200,000 years ago, well-rounded rear of skull (no occipital bun), high skull (doesn’t slope), small brow ridges (supra orbital torus), noticeable chin, associated with Upper Paleolithic tools (some had blades and some were made of bone), created shelters and they were the first to create artistic objects (note cave drawings possible sympathetic magic-related to the desire to capture more animals). Omo- oldest known AMH found at Omo site in Ethiopia—date ~ 195,000ya. Same morphology as noted above. homo heidelbergensis- a species of archaic human w/ a brain size close to that of modern humans (~1500-1800cc’s or more) but had a larger face and lived in Africa, Europe and Asia between 800,000 and 200,000 ya. Cro-Magnon Man- found in Cro-Magnon, France…dates between 27,000-23,000ya, earliest AMH populations found in Europe, very sophisticated, fished, cured ailments, made clothing and jewelry, built rafts etc… complication: Homo Floresiensis “hobbit” Discovered in Liang Bua cave on the island of Flores in Indonesia, 3.5”, 417cc’s found w/ tools and bones, dates between 12,000 and 94,000 ya, possible dwarf species, AMH characteristics. Possible explanations= island dwarfism, microcephalic, pathology, different species= unsure of where it falls on our phylogenic tree PREHISTORIC ART (note Lascaux cave, France) >600 pictures of animals, mostly horses don’t know purpose possible sympathetic magic cultural symbolism? means of communication ideas? pictograph- painting on surface like a cave wall petroglyph- design carved into rock or other surface HUMAN ORIGINS Associated models: (from book as per your syllabus) multiregional model- evolution happened 1.8 mya in Africa from a single lineage but that changes in modern human anatomy happened by way of gene flow as archaic humans moved across the Old World. -

CLOSURE of CRANIAL ARTICULATIONS in the SKULI1 of the AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINE by A

CLOSURE OF CRANIAL ARTICULATIONS IN THE SKULI1 OF THE AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINE By A. A. ABBIE, Department of Anatomy, University of Adelaide INTRODUCTION While it is well known that joint closure advances more or less progressively with age, there is still little certainty in matters of detail, mainly for lack of adequate series of documented skulls. In consequence, sundry beliefs have arisen which tend to confuse the issue. One view, now disposed of (see Martin, 1928), is that early suture closure indicates a lower or more primitive type of brain. A corollary, due to Broca (see Topinard, 1890), that the more the brain is exercised the more is suture closure postponed, is equally untenable. A very widespread belief is based on Gratiolet's statement (see Topinard, 1890; Frederic, 1906; Martin, 1928; Fenner, 1939; and others) that in 'lower' skulls the sutures are simple and commence to fuse from in front, while in 'higher' skulls the sutures are more complicated and tend to fuse from behind. This view was disproved by Ribbe (quoted from Frederic, 1906), who substituted the generalization that in dolicocephals synostosis begins in the coronal suture, and in brachycephals in the lambdoid suture. In addition to its purely anthropological interest the subject raises important biological considerations of brain-skull relationship, different foetalization in different ethnological groups (see Bolk, 1926; Weidenreich, 1941; Abbie, 1947), and so on. A survey of the literature reveals very little in the way of data on the age incidence of suture closure. The only substantial contribution accessible here comes from Todd & Lyon (1924) for Europeans, but their work is marred by arbitrary rejection of awkward material. -

A Description of Some Tasmanian Skulls

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Ramsay Smith, W., 1916. A description of some Tasmanian skulls. Records of the Australian Museum 11(2): 15–29, plates viii–xiii. [1 May 1916]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.11.1916.907 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia A "!:lESGRIPTION OF SOME TASMANIAN SKULLS. By W. RAMSAY SMITH, M.D., D.Sc., F.R.S. (Edin.). (Plates viii-xiii.) I.-INTRODUCTION. III July, 1910, the Trustees of the Aust;>alian Museum, Sydney, were good enough to send me th,' Tasmanian skulls in their collection for the purpose;, 'If meaSl.rement and description. 1'he specimens consisted of two ~omp~ete skulls and the upper portion of a third. About the sa,me time I was fortunate III obtainillg a cast of a skull from the 1'asmaniall Museum, and also, from another source the skull and most of the bones of an aged Tasmanian woman that had not previously been described. 'I'hese specimens form the subject of the present contribution. To Mr. R. Etheridge, Curator of the Australian Museum, I am much indebted for assistance in sending the Museum skulls and giving their origin and history. These description~were writtell nearly five years ago; but the leisure for putting the necessary finishing touches for publication has been long delayed. 1'he sagittal contours (PI.