Workers' Unity, the New Tendency, and Rank-And-File Organizing In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Research, Repression, and Revolution— on Montreal and the Black Radical Tradition: an Interview with David Austin

THE CLR JAMES JOURNAL 20:1-2, Fall 2014 197-232 doi: 10.5840/clrjames201492319 Research, Repression, and Revolution— On Montreal and the Black Radical Tradition: An Interview with David Austin Peter James Hudson " ll roads lead to Montreal" is the title of an essay of yours on Black Montreal in the 1960s published in the Journal of African American History. But can you describe the road that led you to both Montreal and to the historical and theoretical work that you have done on the city over the past decades. A little intellectual biography . I first arrived in Montreal from London, England in 1980 with my brother to join my family. (We had been living with my maternal grandmother in London.) I was almost ten years old and spent two years in Montreal before moving to Toronto. I went to junior high school and high school in Toronto, but Montreal was always a part of my consciousness and we would visit the city on occasion, and I also used to play a lot of basketball so I traveled to Montreal once or twice for basketball tournaments. As a high school student I would frequent a bookstore called Third World Books and Crafts and it was there that I first discovered Walter Rodney's The Groundings with My Brothers. Three chapters in that book were based on presentations delivered by Rodney in Montreal during and after the Congress of Black Writers. So that was my first indication that something unique had happened in Montreal. My older brother Andrew was a college student at the time in Toronto and one day he handed me a book entitled Let the Niggers Burn! The Sir George Williams Affair and its Caribbean Aftermath, edited by Denis Forsythe. -

THE TRAINING of an INTELLECTUAL, the MAKING of a MARXIST, by Richard Small

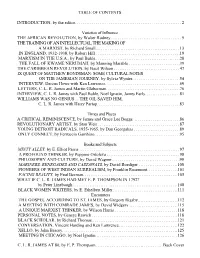

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, by the editor. ........................................................2 Varieties of Influence THE AFRICAN REVOLUTION, by Walter Rodney. ......................................5 THE TRAINING OF AN INTELLECTUAL, THE MAKING OF A MARXIST, by Richard Small...............................................13 IN ENGLAND, 1932-1938, by Robert Hill ..............................................19 MARXISM IN THE U.S.A., by Paul Buhle................................................28 THE FALL OF KWAME NKRUMAH, by Manning Marable ............................39 THE CARIBBEAN REVOLUTION, by Basil Wilson.....................................47 IX QUEST OF MATTHEW BONDSMAN: SOME CULTURAL NOTES ON THE JAMESIAN JOURNEY, by Sylvia Wynter...........................54 INTERVIEW, Darcus Howe with Ken Lawrence. ........................................69 LETTERS, C. L. R. James and Martin Glaberman. .........................................76 INTERVIEW, C. L. R. James with Paul Buhle, Noel Ignatin, James Early. ...................81 WILLIAMS WAS NO GENIUS ... THE OIL SAVED HIM, C. L. R. James with Harry Partap. .83 Times and Places A CRITICAL REMINISCENCE, by James and Grace Lee Boggs. .........................86 REVOLUTIONARY ARTIST, by Stan Weir ............................................87 YOUNG DETROIT RADICALS, 1955-1965, by Dan Georgakas . .89 ONLY CONNECT, by Ferruccio Gambino................................................95 Books and Subjects MINTY ALLEY, by E. Elliot Parris ........................................................97 -

CLR James and the American Century

#12 C.L.R. James and the American Century: 1938-1953 by Kent Worcester Columbia University El Centro de Investigaciones Sociales del Caribe y América Latina (CISCLA) de la Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico, Recinto de San Germán, fue fundado en 1961. Su objetivo fundamental es contribuir a la discusión y análisis de la problemática caribeña y latinoamericana a través de la realización de conferencias, seminarios, simposios e investigaciones de campo, con particular énfasis en problemas de desarrollo político y económico en el Caribe. La serie de Documentos de Trabajo tiene el propósito de difundir ponencias presentadas en actividades de CISCLA así como otros trabajos sobre temas prioritarios del Centro. Para mayor información sobre la serie y copies de los trabajos, de los cuales existe un número limitado para distribución gratuita, dirigir correspondencia a: Dr. Jorge Heine Director de CISCLA Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico Apartado 5100 San Germán, Puerto Rico 00753 The Caribbean Institute and Study Center for Latin America (CISCLA) of Inter American University of Puerto Rico, San Germán Campus, was founded in 1961. Its primary objective is to make a contribution to the discussion and analysis of Caribbean and Latin American issues. The Institute sponsors conferences, seminars, roundtable discussions and field research with a particular emphasis on issues of social, political and economic development in the Caribbean. The Working Paper series makes available to a wider audience work presented at the Institute, as well as other research on subjects of priority interest to CISCLA. Inquiries about the series and individual requests for Working Papers, of which a limited number of copies are available free of charge, should be addressed to: Dr. -

The New Tendency, Autonomist Marxism, and Rank-And-File Organizing in Windsor, Ontario During the 1970S

STRUGGLING FOR A NEW LEFT: THE NEW TENDENCY, AUTONOMIST MARXISM, AND RANK-AND-FILE ORGANIZING IN WINDSOR, ONTARIO DURING THE 1970S A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Sean Antaya 2018 Canadian Studies and Indigenous Studies M.A. Graduate Program September 2018 ABSTRACT Thesis Title: Struggling for a New Left: The New Tendency, Autonomist Marxism, and Rank- and-File Organizing in Windsor, Ontario during the 1970s Author’s Name: Sean Antaya Summary: This study examines the emergence of the New Left organization, The New Tendency, in Windsor, Ontario during the 1970s. The New Tendency, which developed in a number of Ontario cities, represents one articulation of the Canadian New Left’s turn towards working-class organizing in the early 1970s after the student movement’s dissolution in the late 1960s. Influenced by dissident Marxist theorists associated with the Johnson-Forest Tendency and Italian workerism, The New Tendency sought to create alternative forms of working-class organizing that existed outside of, and often in direct opposition to, both the mainstream labour movement and Old Left organizations such as the Communist Party and the New Democratic Party. After examining the roots of the organization and the important legacies of class struggle in Windsor, the thesis explores how The New Tendency contributed to working-class self activity on the shop-floor of Windsor’s auto factories and in the community more broadly. However, this New Left mobilization was also hampered by inner-group sectarianism and a rapidly changing economic context. -

The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939- 1949

The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939- 1949 Victor G. Devinatz Willie Thompson has acknowledged in his survey of the history of the world- wide left, The Left in History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century Politics, that the Trotskyists "occasionally achieved some marginal industrial influence" in the US trade unions.' However, outside of the Trotskyists' role in the Teamsters Union in Minneapolis and unlike the role of the Communist Party (CP) in the US labor movement that has been well-documented in numerous books and articles, little of a systematic nature has been written about Trotskyist activity in the US trade union movement.' This article's goal is to begin to bridge a gap in the historical record left by other historians of labor and radical movements, by examining the role of the two wings of US Trotskyism, repre- sented by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Workers Party (WP), in the United Auto Workers (UAW) from 1939 to 1949. In spite of these two groups' relatively small numbers within the auto workers' union and although neither the SWP nor the WP was particularly suc- cessful in recruiting auto workers to their organizations, the Trotskyists played an active role in the UAW as leading individuals and activists, and as an organ- ized left presence in opposition to the larger and more powerful CP. In addi- tion, these Trotskyists were able to exert an influence that was significant at times, beyond their small membership with respect to vital issues confronting the UAW. At various times throughout the 1940s, for example, these trade unionists were skillful in mobilizing auto unionists in opposition to both the no- strike pledge during World War 11, and the Taft-Hartley bill in the postwar peri- od. -

The Double Bind: the Politics of Racial & Class Inequalities in the Americas

THE DOUBLE BIND: THE POLITICS OF RACIAL & CLASS INEQUALITIES IN THE AMERICAS Report of the Task Force on Racial and Social Class Inequalities in the Americas Edited by Juliet Hooker and Alvin B. Tillery, Jr. September 2016 American Political Science Association Washington, DC Full report available online at http://www.apsanet.org/inequalities Cover Design: Steven M. Eson Interior Layout: Drew Meadows Copyright ©2016 by the American Political Science Association 1527 New Hampshire Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-878147-41-7 (Executive Summary) ISBN 978-1-878147-42-4 (Full Report) Task Force Members Rodney E. Hero, University of California, Berkeley Juliet Hooker, University of Texas, Austin Alvin B. Tillery, Jr., Northwestern University Melina Altamirano, Duke University Keith Banting, Queen’s University Michael C. Dawson, University of Chicago Megan Ming Francis, University of Washington Paul Frymer, Princeton University Zoltan L. Hajnal, University of California, San Diego Mala Htun, University of New Mexico Vincent Hutchings, University of Michigan Michael Jones-Correa, University of Pennsylvania Jane Junn, University of Southern California Taeku Lee, University of California, Berkeley Mara Loveman, University of California, Berkeley Raúl Madrid, University of Texas at Austin Tianna S. Paschel, University of California, Berkeley Paul Pierson, University of California, Berkeley Joe Soss, University of Minnesota Debra Thompson, Northwestern University Guillermo Trejo, University of Notre Dame Jessica L. Trounstine, University of California, Merced Sophia Jordán Wallace, University of Washington Dorian Warren, Roosevelt Institute Vesla Weaver, Yale University Table of Contents Executive Summary The Double Bind: The Politics of Racial and Class Inequalities in the Americas . -

Rothbard's Time on the Left

ROTHBARD'S TIME ON THE LEFT MURRAY ROTHBARD DEVOTED HIS life to the struggle for liberty, but, as anyone who has made a similar commitment realizes, it is never exactly clear how that devotion should translate into action. Conse- quently, Rothbard formed strategic alliances with widely different groups throughout his career. Perhaps the most intriguing of these alliances is the one Rothbard formed with the New Left in the rnid- 1960s, especially considering their antithetical economic views. So why would the most free market of free-market economists reach out to a gaggle of assorted socialists? By the early 1960s, Roth- bard saw the New Right, exemplified by National Review, as perpet- ually wedded to the Cold War, which would quickly turn exponen- tially hotter in Vietnam, and the state interventions that accompanied it, so he set out looking for new allies. In the New Left, Rothbard found a group of scholars who opposed the Cold War and political centralization, and possessed a mass following with high growth potential. For this opportunity, Rothbard was willing to set economics somewhat to the side and settle on common ground, and, while his cooperation with the New Left never altered or caused him to hide any of his foundational beliefs, Rothbard's rhetoric shifted distinctly leftward during this period. It should be noted at the outset that Rothbard's pro-peace stance followed a long tradition of individualist intellectuals. Writing in the early 1970s, Rothbard described the antiwar activities of turn-of-the- century economist William Graham Sumner and merchant Edward Atkinson during the American conquest of the Philippines, and noted: In taking this stand, Atkinson, Surnner, and their colleagues were not being "sports"; they were following an anti-war, anti-imperial- ist tradition as old as classical liberalism itself. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ PRECARIOUS CITY: MARGINAL WORKERS, THE STATE, AND WORKING-CLASS ACTIVISM IN POST-INDUSTRIAL SAN FRANCISCO, 1964-1979 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Laura Renata Martin March 2014 The dissertation of Laura Renata Martin is approved: ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Dana Frank, chair ------------------------------------------------------- Professor David Brundage ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Alice Yang ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Eileen Boris ------------------------------------------------------- Tyrus Miller, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents Introduction. 1 Chapter One. The War Over the War on Poverty: Civil Rights Groups, the War on Poverty, and the “Democratization” of the Great Society 53 Chapter Two. Crisis of Social Reproduction: Organizing Around Public Housing and Welfare Rights 107 Chapter Three. Policing and Black Power: The Hunters Point Riot, The San Francisco Police Department, and The Black Panther Party 171 Chapter Four. Labor Against the Working Class: The International Longshore Workers’ Union, Organized Labor, and Downtown Redevelopment 236 Chapter Five. Contesting Sexual Labor in the Post-Industrial City: Prostitution, Policing, and Sex Worker Organizing in the Tenderloin 296 Conclusion. 364 Bibliography. 372 iii Abstract Precarious City: Marginal Workers, the State, and Working-Class Activism in Post- Industrial San Francisco, 1964-1979 Laura Renata Martin This project investigates the effects of San Francisco’s transition from an industrial to a post-industrial economy on the city’s social movements between 1964 and 1979. I re-contextualize the city’s Black freedom, feminist, and gay and transgender liberation movements as struggles over the changing nature of urban working-class life and labor in the postwar period. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

“To Work, Write, Sing and Fight for Women's Liberation”

“To work, write, sing and fight for women’s liberation” Proto-Feminist Currents in the American Left, 1946-1961 Shirley Chen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 30, 2011 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For my mother Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... ii Introduction...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter I: “An End to the Neglect” ............................................................................ 10 Progressive Women & the Communist Left, 1946-1953 Chapter II: “A Woman’s Place is Wherever She Wants it to Be” ........................... 44 Woman as Revolutionary in Marxist-Humanist Thought, 1950-1956 Chapter III: “Are Housewives Necessary?” ............................................................... 73 Old Radicals & New Radicalisms, 1954-1961 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 106 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 111 Acknowledgements First, I am deeply grateful to my adviser, Professor Howard Brick. From helping me formulate the research questions for this project more than a year ago to reading last minute drafts, his -

CLR James, His Early Relationship to Anarchism and the Intellectual

This is a repository copy of A “Bohemian freelancer”? C.L.R. James, his early relationship to anarchism and the intellectual origins of autonomism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90063/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Hogsbjerg, CJ (2012) A “Bohemian freelancer”? C.L.R. James, his early relationship to anarchism and the intellectual origins of autonomism. In: Prichard, A, Kinna, R, Pinta, S and Berry, D, (eds.) Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan , Basingstoke . ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3 © 2012 Palgrave Macmillan. This is an author produced version of a chapter published in Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request.