Remapping the American Left: a History of Radical Discontinuity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Left Info Flyer

United for a left alternative in Europe United for a left alternative in Europe ”We refer to the values and traditions of socialism, com- munism and the labor move- ment, of feminism, the fem- inist movement and gender equality, of the environmental movement and sustainable development, of peace and international solidarity, of hu- man rights, humanism and an- tifascism, of progressive and liberal thinking, both national- ly and internationally”. Manifesto of the Party of the European Left, 2004 ABOUT THE PARTY OF THE EUROPEAN LEFT (EL) EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board was elected at the 4th Congress of the Party of the European Left, which took place from 13 to 15 December 2013 in Madrid. The Executive Board consists of the President and the Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and other Members elected by the Congress, on the basis of two persons of each member party, respecting the principle of gender balance. COUNCIL OF CHAIRPERSONS The Council of Chairpersons meets at least once a year. The members are the Presidents of all the member par- ties, the President of the EL and the Vice-Presidents. The Council of Chairpersons has, with regard to the Execu- tive Board, rights of initiative and objection on important political issues. The Council of Chairpersons adopts res- olutions and recommendations which are transmitted to the Executive Board, and it also decides on applications for EL membership. NETWORKS n Balkan Network n Trade Unionists n Culture Network Network WORKING GROUPS n Central and Eastern Europe n Africa n Youth n Agriculture n Migration n Latin America n Middle East n North America n Peace n Communication n Queer n Education n Public Services n Environment n Women Trafficking Member and Observer Parties The Party of the European Left (EL) is a political party at the Eu- ropean level that was formed in 2004. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

E42 Mark Blyth & David Kertzer Mixdown

Brown University Watson Institute | E42_Mark Blyth & David Kertzer_mixdown [MUSIC PLAYING] MARK BLYTH: Hello, and welcome to a special edition of Trending Globally. My name is Mark Blyth. Today, I'm interviewing David Kertzer. David is the former provost here at Brown University. But perhaps more importantly, he knows more about Italy than practically anybody else we can find. Given that the elections have just happened in Italy and produced yet another kind of populist shock, we thought is was a good idea to bring him in and have a chat. Good afternoon, David. DAVID KERTZER: Thanks for having me, Mark. MARK BLYTH: OK, so let's try and put this in context for people. Italy's kicked off. Now, we could talk about what's happening right now today, but to try and get some context on this, I want to take us back a little bit. This is not the first time the Italian political system-- indeed the whole Italian state-- has kind of blown up. I want to go back to 1994. That's the last time things really disintegrated. Start there, and then walk forward, so then we can talk more meaningfully about the election. So I'm going to invite you to just take us back to 1994. Tell us about what was going on-- the post-war political compact, and then [BLOWS RASPBERRY] the whole thing fell apart. DAVID KERTZER: Well, right after World War II, of course, it was a new political system-- the end of the monarchy. There is a republic. The Christian Democratic Party, very closely allied with the Catholic Church, basically dominated Italian politics for decades. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

House of the Beehives

2016 2017 put SEASON Loren here 24 House of the Beehives Dušan Bogdanović Canticles for Two Guitars (1998) 10 min Michael Goldberg, Marc Teicholz guitar Maurice Ravel Sonata for Violin and Cello (1922) 20 min I Allegro II Très vif III Lent IV Vif, avec entrain Anna Presler violin • Leighton Fong cello David Coll Ghost Dances (2016) 5 min WORLD PREMIERE Stacey Pelinka flute • Andrea Plesnarski oboe • Phyllis Kamrin violin Leighton Fong cello • Michael Goldberg, Marc Teicholz guitar INTERMISSION Melody Eötvös House of the Beehives for Flute, Oboe, and Electronics (2015) 19 min WINNER OF THE LCCE COMPOSITION CONTEST I Hermit (chorale) II Bees (toccata) III Into the Woods (the wall) IV The Encounter ...to see the terror and shame in her eyes V The Hermit (Like a sinking memory-go-around) Stacey Pelinka flute • Andrea Plesnarski oboe Sebastian Currier Broken Consort (1996) 15 min Stacey Pelinka flute • Andrea Plesnarski oboe • Phyllis Kamrin violin Leighton Fong cello • Michael Goldberg, Marc Teicholz guitar Left Coast gratefully acknowledges the support of San Francisco Hotel Tax Fund Grants for the Arts. Saturday, February 4, 7:30 pm The Hillside Club, Berkeley Monday, February 6, 7:30 pm San Francisco Conservatory of Music notes and biographies Dušan Bogdanović Maurice Ravel Canticles for Two Guitars (1998) Sonata for Violin and Cello (1922) anticles was commissioned in 1998 by the Gruber- he music is stripped to the bone,” said Maurice Ravel CMaklar duo. Though the influences are recognizable, Tof his Sonata for Violin and Cello. As if harmony Canticles is not necessarily based on any specific religious were some sort of seducer, he said he had rejected its chant; it is a sort of an intuitively composed spiritual “allure” in this work, and focused on melody instead. -

Special Editions 133

MILAN St. PROTIĆ BETWEEN DEMOCRACY AND POPULISM POLITICAL IDEAS OF THE PEOPLE’S RADICAL PARTY IN SERBIA (The Formative Period: 1860’s to 1903) BETWEEN AND POPULISM DEMOCRACY , Protić . t M. S ISBN 978-86-7179-094-9 BELGRADE 2015 http://www.balkaninstitut.com MILAN St. PROTIĆ BETWEEN DEMOCRACY AND POPULISM POLITICAL IDEAS OF THE PEOPLE’S RADICAL PARTY IN SERBIA (The Formative Period: 1860’s to 1903) http://www.balkaninstitut.com INSTITUTE FOR BALKAN STUDIES SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS SPECIAL EDITIONS 133 MILAN St. PROTIĆ BETWEEN DEMOCRACY AND POPULISM POLITICAL IDEAS OF THE PEOPLE’S RADICAL PARTY IN SERBIA (The Formative Period: 1860’s to 1903) Editor-in-Chief Dušan T. Bataković Director of the Institute for Balkan Studies BELGRADE 2015 http://www.balkaninstitut.com Publisher Institute for Balkan Studies Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Belgrade, Knez Mihailova 35/IV Serbia www.balkaninstitut.com e-mail: [email protected] Reviewers Vojislav Stanovčić, member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Vojislav Pavlović, Institute for Balkan Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Written in English by Author Design by Kranislav Vranić Printed by SVEN, Niš ISBN 978-86-7179-094-9 http://www.balkaninstitut.com Table of Contents Preface . 7 Prologue . 11 Chapter One THE ORIGINS . 17 Chapter Two THE HISTORY . 35 Chapter Three THE SOURCES . 61 Chapter Four THE CHARACTERISTICS . 83 Chapter Five THE STRUCTURE . 103 Chapter Six THE LEADERS . 121 EPILOGUE . 149 Bibliography. 173 Index . 185 http://www.balkaninstitut.com http://www.balkaninstitut.com PREFACE hen, upon my return from Bern, Switzerland, it was suggested to me Wto consider the publication of my Ph.D. -

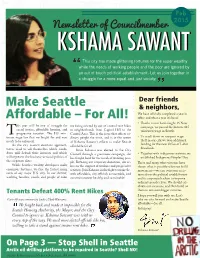

Make Seattle Affordable—For All

Feb 2015 Newsletter of Councilmember KSHAMAKSHAMA SAWANTSAWANT This city has made glittering fortunes for the super wealthy while the needs of working people and the poor are ignored by an out of touch political establishment. Let us join together in a struggle for a more equal and just society. Dear friends Make Seattle & neighbors, We have officially completed a year in Affordable – For All! office and what a year it’s been! • Thanks to our hard-fought 15 Now his year will be one of struggle for are being evicted by out-of-control rent hikes campaign, we passed the historic $15 racial justice, affordable housing, and in neighborhoods from Capitol Hill to the minimum wage in Seattle. progressive taxation. The $15 min- Central Area. This is the issue that affects -or imum wage law that we fought for and won dinary people the most, and is at the center • To crack down on rampant wage T theft in our city, we won additional needs to be enforced. of Kshama Sawant´s efforts to make Seattle funding for the new Office of Labor As the city council elections approach, affordable for all. Standards. voters need to ask themselves which candi- Since Kshama was elected to the City dates will defend their interests and which Council through a grassroots campaign, she • Together with indigenous activists, we will represent the business-as-usual politics of has fought hard for the needs of working peo- established Indigenous Peoples’ Day. the corporate elites. ple. Refusing any corporate donations, she re- These and many other victories have While Seattle’s wealthy developers make lies on the support of workers and progressive shown what is possible when we build enormous fortunes, we face the fastest rising activists. -

In Defense of Kshama Sawant

In Defense of Kshama Sawant Call it a voter-suppression effort, ex post facto. The attempt to remove Kshama Sawant from her seat on Seattle’s City Council through a recall petition is a blatant attack on the democratic rights of constituents — and on the emergence of a new socialist left as a current in American politics. Sawant is the public face of Socialist Alternative, one of numerous small Marxist organizations in the United States. But defending her from corporate and right-wing attack is an issue that everyone on the left in the United States should support. Sawant has been elected to her position three times now, running on a platform of solidarity with the Seattle’s workers — backed up by heavy and long overdue taxation of the city’s millionaires and billionaires. In the summer of 2020 she gave full support to Black Lives Matter. And that seems to have been the proverbial straw breaking the camel’s back: Sawant’s activity in solidarity with BLM features prominently in the recall campaign’s complaints about her. With hindsight, it’s clear that Sawant’s election to City Council in 2013 foreshadowed the groundswell of support for Bernie Sanders’s presidential run in 2016. The platform for her first campaign included public ownership of Washington state’s corporate behemoths, including Microsoft and Amazon. More recently, her page on the City Council website has demanded taxation “to fund immediate COVID-19 relief for working people, and then to go on in 2021 and beyond to fund a massive expansion of new, affordable, social housing and Green New Deal renovations of existing homes.” In 2019, Amazon contributed $1.5 million to a political action committee opposed to Sawant, who was reelected anyway. -

Imperialism, Racism, and Fear of Democracy in Richard Ely's Progressivism

The Rot at the Heart of American Progressivism: Imperialism, Racism, and Fear of Democracy in Richard Ely's Progressivism Gerald Friedman Department of Economics University of Massachusetts at Amherst November 8, 2015 This is a sketch of my long overdue intellectual biography of Richard Ely. It has been way too long in the making and I have accumulated many more debts than I can acknowledge here. In particular, I am grateful to Katherine Auspitz, James Boyce, Bruce Laurie, Tami Ohler, and Jean-Christian Vinel, and seminar participants at Bard, Paris IV, Paris VII, and the Five College Social History Workshop. I am grateful for research assistance from Daniel McDonald. James Boyce suggested that if I really wanted to write this book then I would have done it already. And Debbie Jacobson encouraged me to prioritize so that I could get it done. 1 The Ely problem and the problem of American progressivism The problem of American Exceptionalism arose in the puzzle of the American progressive movement.1 In the wake of the Revolution, Civil War, Emancipation, and radical Reconstruction, no one would have characterized the United States as a conservative polity. The new Republican party took the United States through bloody war to establish a national government that distributed property to settlers, established a national fiat currency and banking system, a progressive income tax, extensive program of internal improvements and nationally- funded education, and enacted constitutional amendments establishing national citizenship and voting rights for all men, and the uncompensated emancipation of the slave with the abolition of a social system that had dominated a large part of the country.2 Nor were they done. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

Portland Efiles

Offico of the Secretary. ASSJCI.A'I'ED PARl'IERS OF CALIFOPJHA Inc::,j~porated 1301 Ho"ts.rt Bu.iJ.o.in1~ - 582 IV".tarlrnt St. San F~ancisco, Calif. The following information has been received by us from many sour0es ... clippings and references. It is believed to be reliable and authentic and is forwarded to you for your information and use. Sincerely yours., ASSOCIATED FARMERS OF CALIFOTINB., nw. By: GUERNSEY FR.AZER ·- -·Executive Secretary. REPORT ON LEO GALLAGHER ACLU Bull - American Civil Liberties Union weekly bulletin. CDT - Chicago Daily Times. CT - Chicago Tribune. DM - Daily J\1aroon ( Uni versiJcy of Chicago student paper). FP - Federated Press clipsheet. ( Communist press service). LA'.!.' - Los Angeles Times LD - Labor Defender. ( Official organ of International Labor Defense). ML - Milwaukee Leader (Wdlwaukes Socialist paper). NM - Communist weekly magazine New Masses. NS - New Student ( National Student Lea6"1.1.e at Univ. of Wisconsin magazine). NYTel - New York Telegram. NYT - New York Times. SR - Student Review ( Official organ Ne.tional Student League). VA ... Voice of Action (Officid Communist Party District 12 paper at Seattle). WW - 1.'V'estern Worker ( Official Co. Party Dist. 13 pe.per, San Francisco.) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Leo Gallagher, professor of Law at Southwestern University., Los A.'lgeles, Cp_l i.fornia froJ'.'1 1922 to 1932 w-as for a number of year:; an al;tornoy for the American Civil Liberties Union in Los Angeles from which he graduated to the Communist 11 Inte:rnational Labor Defense" being the leading Communist attorney on the Pacific Coast. Ga.lla.i;;her was Treasurer of the Communist "Friends of the Soviet Union in 1930 (Page 50 Pa.rt v. -

Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions

Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions The Supreme Court case Janus v. AFSCME is poised to decimate public-sector unions—and it’s been made possible by a network of right-wing billionaires, think tanks and corporations. MARY BOTTARI FEBRUARY 22, 2018 | MARCH ISSUE In These Times THE ROMAN GOD JANUS WAS KNOWN FOR HAVING TWO FACES. It is a fitting name for the U.S. Supreme Court case scheduled for oral arguments February 26, Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Council 31, that could deal a devastating blow to public-sector unions and workers nationwide. In the past decade, a small group of people working for deep-pocketed corporate interests, conservative think tanks and right-wing foundations have bankrolled a series of lawsuits to end what they call “forced unionization.” They say they fight in the name of “free speech,” “worker rights” and “workplace freedom.” In briefs before the court, they present their public face: carefully selected and appealing plaintiffs like Illinois child-support worker Mark Janus and California schoolteacher Rebecca Friedrichs. The language they use is relentlessly pro-worker. Behind closed doors, a different face is revealed. Those same people cheer “defunding” and “bankrupting” unions to deal a “mortal blow” to progressive politics in America. A key director of this charade is the State Policy Network (SPN), whose game plan is revealed in a union-busting toolkit uncovered by the Center for Media and Democracy. The first rule of the national network of right-wing think tanks that are pushing to dismantle unions? “Rule #1: Be pro-worker, not anti-union.