Islamism, Secularism, and Public Order in the Tunisian Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ennahda's Approach to Tunisia's Constitution

BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER ANALYSIS PAPER Number 10, February 2014 CONVINCE, COERCE, OR COMPROMISE? ENNAHDA’S APPROACH TO TUNISIA’S CONSTITUTION MONICA L. MARKS B ROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high- quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its scholars. Copyright © 2014 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha TABLE OF C ONN T E T S I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 III. Diverging Assessments .................................................................................................4 IV. Ennahda as an “Army?” ..............................................................................................8 V. Ennahda’s Introspection .................................................................................................11 VI. Challenges of Transition ................................................................................................13 -

Liste Des Chaînes TV

les 4 Bouquets PaCK à La FOLIE autres Bouquets et chaînes TV jusqu’à 220 chaînes incluses thématiques dont toutes les chaînes du pack UN PEU et du pack SFR Sport, Family, Sports et Kids à la carte en option BEAUCOUP et un bouquet thématique à choix La TV selon vos affinités SFR Sport 10.–/mois LES CHAÎNES CANAL+ 55.–/mois Bouquet ALBANAIS 20.–/mois N° Chaîne HD Langue OFFERT! N° Chaîne HD Langue N° Chaîne HD Langue 141 SFR Sport 1 HD fr 100 CANAL+ HD fr 500 TVSH Sat al 142 SFR Sport 2 HD fr Un bouquet thématique SFR Sport, 101 CANAL+ CINEMA HD fr 501 Kohavision HD al 143 SFR Sport 3 HD fr FAMILY, SPORTS ou KIDS est 102 CANAL+ SPORT HD fr 502 RTV 21 HD al 145 SFR Sport 5 HD fr inclus gratuitement dans le pack 103 CANAL+ FAMILY HD fr 503 Klan Kosova HD al 104 CANAL+ DECALE HD fr 504 Arta al à la folie! 105 CANAL+ SERIES HD fr Bouquet ARABIA 10.–/mois Chaîne en option du bouquet CANAL+ 9.50/mois N° Chaîne HD Langue 106 GOLF+ HD fr 510 MBC ar 511 MBC Masr ar FAMILY 10.–/mois SPORTS 10.–/mois KIDS 10.–/mois Bouquet LES+ 20.–/mois 512 Nessma ar N° Chaîne L N° Chaîne L N° Chaîne L N° Chaîne HD Langue 513 Dubai TV ar 150 Discovery Channel fr 172 MCS Tennis fr 130 Disney Junior fr 110 CINE+ PREMIER HD fr 514 LBC ar 151 Discovery Science fr 173 MCS Bien-être fr 131 Disney Cinema fr 111 CINE+ FRISSON HD fr 515 Al Jadeed ar 152 National Geographic Wild fr 174 Eurosport 2 fr 132 Disney XD fr 112 CINE+ EMOTION HD fr 516 Mazzika ar 153 Toute l'histoire fr 175 Golf Channel fr 133 Nickelodeon fr 113 CINE+ FAMIZ -

Morocco Awards 2013″ : Promouvoir Les Marques Marocaines

MOROCCO AWARDS 2013 Revue de presse de la 5ième édition OUVERTURE DES INSCRIPTIONS Conférence de presse du 19 septembre 2013 Casablanca Annonce presse « Lancement des inscriptions aux Morocco Awards 2013 » Support : Le Matin – 21 Septembre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards 2013 : La course est ouverte ! Support : L’Economiste – 23 Septembre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards : Top départ des candidatures Support : Aujourd’hui le Maroc– 23 Septembre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards 2013 : Le Design à l’honneur Support : L’Observateur du Maroc– du 27 septembre au 03 octobre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards : La course est lancée ! Support : Food Magazine– du 15 septembre au 15 octobre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards : Présentation de la 5ème édition Support : Le Matin – 18 octobre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards 2013 : Les inscriptions bouclées ce dimanche Support : Resagro – Octobre/Novembre 2013 Titre : “Morocco Awards 2013” Ouverture des inscriptions jusqu’au 20 octobre Presse électronique Support : www.infomediaire.ma Titre : Morocco Awards 2013 : Les candidatures sont ouvertes Support : www.lnt.ma (La Nouvelle Tribune) – Septembre 2013 Titre : Morocco Awards 2013 : Promouvoir les marques marocaines “Morocco Awards 2013″ : Promouvoir les marques marocaines Support : www.financenews.press.ma Titre : Morroco Awards 2013 : Ouverture des inscriptions Support : www.liberation.ma – 24 septembre 2013 Titre : Les candidatures sont ouvertes Support : www.marqueimedia.com– Septembre 2013 Titre : Ouverture des inscriptions jusqu’au 20 octobre Support : www.resagro.com– Septembre -

LES CHAÎNES TV by Dans Votre Offre Box Très Haut Débit Ou Box 4K De SFR

LES CHAÎNES TV BY Dans votre offre box Très Haut Débit ou box 4K de SFR TNT NATIONALE INFORMATION MUSIQUE EN LANGUE FRANÇAISE NOTRE SÉLÉCTION POUR VOUS TÉLÉ-ACHAT SPORT INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE MULTIPLEX SPORT & ÉCONOMIQUE EN VF CINÉMA ADULTE SÉRIES ET DIVERTISSEMENT DÉCOUVERTE & STYLE DE VIE RÉGIONALES ET LOCALES SERVICE JEUNESSE INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE CHAÎNES GÉNÉRALISTES NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION MONDE 0 Mosaïque 34 SFR Sport 3 73 TV Breizh 1 TF1 35 SFR Sport 4K 74 TV5 Monde 2 France 2 36 SFR Sport 5 89 Canal info 3 France 3 37 BFM Sport 95 BFM TV 4 Canal+ en clair 38 BFM Paris 96 BFM Sport 5 France 5 39 Discovery Channel 97 BFM Business 6 M6 40 Discovery Science 98 BFM Paris 7 Arte 42 Discovery ID 99 CNews 8 C8 43 My Cuisine 100 LCI 9 W9 46 BFM Business 101 Franceinfo: 10 TMC 47 Euronews 102 LCP-AN 11 NT1 48 France 24 103 LCP- AN 24/24 12 NRJ12 49 i24 News 104 Public Senat 24/24 13 LCP-AN 50 13ème RUE 105 La chaîne météo 14 France 4 51 Syfy 110 SFR Sport 1 15 BFM TV 52 E! Entertainment 111 SFR Sport 2 16 CNews 53 Discovery ID 112 SFR Sport 3 17 CStar 55 My Cuisine 113 SFR Sport 4K 18 Gulli 56 MTV 114 SFR Sport 5 19 France Ô 57 MCM 115 beIN SPORTS 1 20 HD1 58 AB 1 116 beIN SPORTS 2 21 La chaîne L’Équipe 59 Série Club 117 beIN SPORTS 3 22 6ter 60 Game One 118 Canal+ Sport 23 Numéro 23 61 Game One +1 119 Equidia Live 24 RMC Découverte 62 Vivolta 120 Equidia Life 25 Chérie 25 63 J-One 121 OM TV 26 LCI 64 BET 122 OL TV 27 Franceinfo: 66 Netflix 123 Girondins TV 31 Altice Studio 70 Paris Première 124 Motorsport TV 32 SFR Sport 1 71 Téva 125 AB Moteurs 33 SFR Sport 2 72 RTL 9 126 Golf Channel 127 La chaîne L’Équipe 190 Luxe TV 264 TRACE TOCA 129 BFM Sport 191 Fashion TV 265 TRACE TROPICAL 130 Trace Sport Stars 192 Men’s Up 266 TRACE GOSPEL 139 Barker SFR Play VOD illim. -

Print This Article

ISSN: 2051-0861 Publication details, including guidelines for submissions: https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/nmes From Dictatorship to “Democracy”: Neoliberal Continuity and Its Crisis in Tunisia Author(s): Mehmet Erman Erol To cite this article: Erol, Mehmet Erman (2020) ―From Dictatorship to ―Democracy‖: Neoliberal Continuity and Its Crisis in Tunisia‖, New Middle Eastern Studies 10 (2), pp. 147- 163. Online Publication Date: 30 December 2020 Disclaimer and Copyright The NMES editors make every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information contained in the journal. However, the Editors and the University of Leicester make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness or suitability for any purpose of the content and disclaim all such representations and warranties whether express or implied to the maximum extent permitted by law. Any views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and not the views of the Editors or the University of Leicester. Copyright New Middle Eastern Studies, 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from New Middle Eastern Studies, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed, in writing. Terms and Conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

Retombees-Medias-Tunis-Forum.Pdf

Retombées Médias 5ème édition Tunis Forum Tunisie – Chine : un partenariat d’avenir Business News http://bit.ly/2tVpG7o Entreprises Magazine http://bit.ly/2v2u02i Entreprises Magazine http://bit.ly/2sW6yal ilBoursa http://bit.ly/2v2AUEO ilBoursa http://bit.ly/2uHFR6l Espace Manager http://bit.ly/2v2wuxs Espace Manager http://bit.ly/2v32GRn Tunisie Tribune http://bit.ly/2tF7UDq Maghreb Emergent http://bit.ly/2tZ8aQd Webmanagercenter http://bit.ly/2tFACEp Webmanagercenter http://bit.ly/2tFEF3k Globalnet http://bit.ly/2v2prVH L’Economiste Maghrebin http://bit.ly/2t4UAWS L’Economiste Maghrebin http://bit.ly/2v2KEP8 L’Economiste Maghrebin http://bit.ly/2tZmXKA L’Economiste Maghrebin http://bit.ly/2v3gSdk French Xinhua http://bit.ly/2t4sM4X French China http://on.china.cn/2t8syKm Tekiano http://bit.ly/2sBJD3H L’Instant M http://bit.ly/2tFxfgB Le Manager http://bit.ly/2u9bXe7 Le Manager http://bit.ly/2ucQpNX Webdo http://bit.ly/2uIaCYL Chroniques de Tunipages http://bit.ly/2v3fs2u La Presse http://bit.ly/2tYZIk2 Carthago News http://bit.ly/2u9qHdi Africa Time http://bit.ly/2tyXZ3Z Avant Première Magazine http://bit.ly/2szUsiO Le Temps http://bit.ly/2v35wpx Highlights http://bit.ly/2sWdjcl Le Point.tn http://bit.ly/2sZkjVO African Manager http://bit.ly/2tD6ydO African Manager http://bit.ly/2u3bpGd Kapitalis http://bit.ly/2t4tQ8Y Kapitalis http://bit.ly/2sVyL0S Kapitalis http://bit.ly/2v6O2Zp TAP http://bit.ly/2sWjyN0 TAP http://bit.ly/2tyW7bs TAP http://bit.ly/2v2uiWX TAP http://bit.ly/2sZzkqp TAP http://bit.ly/2t951bY TAP http://bit.ly/2ucLlJi -

Re-Configurations Contextualising Transformation Processes and Lasting Crises in the Middle East and North Africa Politik Und Gesellschaft Des Nahen Ostens

Politik und Gesellschaft des Nahen Ostens Rachid Ouaissa · Friederike Pannewick Alena Strohmaier Editors Re-Configurations Contextualising Transformation Processes and Lasting Crises in the Middle East and North Africa Politik und Gesellschaft des Nahen Ostens Series Editors Martin Beck, Institute of History, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Cilja Harders, Institut für Politikwissenschaft, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany Annette Jünemann, Institut für Internationale Politik, Helmut Schmidt Universität, Hamburg, Germany Rachid Ouaissa, Centrum für Nah- und Mittelost-Stud, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany Stephan Stetter, Institut für Politikwissenschaften, Universität der Bundeswehr München, München, Germany Die Reihe beschäftigt sich mit aktuellen Entwicklungen und Umbruchen̈ in Nor- dafrika, dem Nahen Osten, der Golfregion und darüber hinaus. Die politischen, sozialen und ökonomischen Dynamiken in der Region sind von hoher globaler Bedeutung und sie strahlen intensiv auf Europa aus. Die Reihe behandelt die gesa- mte Bandbreite soziopolitischer Themen in der Region: Veränderungen in Konfikt- mustern und Kooperationsbeziehungen in Folge der Arabischen Revolten 2010/11 wie etwa Euro-Arabische und Euro-Mediterrane Beziehungen oder den Nahost- konfikt. Auf nationaler Ebene geht es um Themen wie Reform, Transformation und Autoritarismus, Islam und Islamismus, soziale Bewegungen, Geschlechterver- hältnisse aber auch energie- und umweltpolitische Fragen, Migrationsdynamiken oder neue Entwicklungen in der Politischen Ökonomie. Der Schwerpunkt liegt auf innovativen politikwissenschaftlichen Werken, die die gesamte theoretische Breite des Faches abdecken. Eingang fnden aber auch Beiträge aus anderen sozialwissen- schaftlichen Disziplinen, die relevante politische Zusammenhänge behandeln. This book series focuses on key developments in the Middle East and North Africa as well as the Gulf and beyond. The regions’ political, economic and social dynam- ics are of high global signifcance, not the least for Europe. -

The Development of Libyan- Tunisian Bilateral Relations: a Critical Study on the Role of Ideology

THE DEVELOPMENT OF LIBYAN- TUNISIAN BILATERAL RELATIONS: A CRITICAL STUDY ON THE ROLE OF IDEOLOGY Submitted by Almabruk Khalifa Kirfaa to the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics In December 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: Almabruk Kirfaa………………………………………………………….. i Abstract Libyan-Tunisian bilateral relations take place in a context shaped by particular historical factors in the Maghreb over the past two centuries. Various elements and factors continue to define the limitations and opportunities present for regimes and governments to pursue hostile or negative policies concerning their immediate neighbours. The period between 1969 and 2010 provides a rich area for the exploration of inter-state relations between Libya and Tunisia during the 20th century and in the first decade of the 21st century. Ideologies such as Arabism, socialism, Third Worldism, liberalism and nationalism, dominated the Cold War era, which saw two opposing camps: the capitalist West versus the communist East. Arab states were caught in the middle, and many identified with one side over the other. generating ideological rivalries in the Middle East and North Africa. The anti-imperialist sentiments dominating Arab regimes and their citizens led many statesmen and politicians to wage ideological struggles against their former colonial masters and even neighbouring states. -

2019 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections in Tunisia Final Report

ELECTION REPORT ✩ 2019 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections in Tunisia Final Report ELECTION REPORT ✩ 2019 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections in Tunisia Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5100 www.cartercenter.org Contents Map of Tunisia................................. 4 The Independent High Authority Executive Summary ............................ 5 for Audiovisual Communications .............. 40 Background ................................. 6 Conclusion ................................ 41 Legal Framework ............................ 7 Candidates, Parties, and Campaigns ........... 42 Election Management ........................ 7 Campaigning in the First Round Voter Registration ........................... 8 of the Presidential Election .................. 42 Voter Education ............................. 8 Conclusion ................................ 44 Citizen Observation .......................... 8 Campaigning in the Parliamentary Election .... 44 Candidate Registration ....................... 8 Campaigning in the Second Round of the Campaign .................................. 9 Presidential Election ........................ 46 Voting and Counting ........................ 11 Campaign Finance ............................ 47 Tabulation ................................. 12 Social Media Monitoring ...................... 49 Electoral Dispute Resolution ................. 12 Legal Framework ........................... 49 Results .................................... 13 Methodology ............................. -

Tunisian Theater at the Turn of the Century: "Hammering the Same Nail" in Jalila Baccar and Fadhel Jaïbi's Theater Rafika Zahrouni Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 3-11-2014 Tunisian Theater at the Turn of the Century: "Hammering the Same Nail" in Jalila Baccar and Fadhel Jaïbi's Theater Rafika Zahrouni Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Zahrouni, Rafika, "Tunisian Theater at the Turn of the Century: "Hammering the Same Nail" in Jalila Baccar and Fadhel Jaïbi's Theater" (2014). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1274. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1274 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Program in Comparative Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: Nancy Berg, Chair Robert Hegel Robert Henke Pascal Ifri Lynne Tatlock Tunisian Theater at the Turn of the Century: “Hammering the Same Nail” in Jalila Baccar and Fadhel Jaïbi’s Theater by Rafika Zahrouni A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 St. Louis, Missouri Copyright by Rafika Zahrouni © 2014 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………….……….. iii Introduction: From Edison Theater in St. Louis to the New Theater of Tunis ….................... 1 Chapter 1: Background of Tunisian Theater History ……………………………….…......... 17 Chapter 2: The Development of the New Theater ………………………………………….. 58 Chapter 3: From Silence to Madness, from Madness to Speech: The Psychiatric Institution as Metaphor …………………………………………………………………………………. -

Political Finance and Gender Equality

Political Finance and Gender Equality Lolita Cigane and Magnus Ohman August 2014 White Paper Series Paper White TION F DA OR N E U L O E F C T L O A R N I A O L I S T Y A F Global Expertise. Local Solutions. S N T R E E M T E Sustainable Democracy. S N I S 2 5 Y E A R S Political Finance and Gender Equality Lolita Cigane and Magnus Ohman IFES White Paper August 2014 Political Finance and Gender Equality Copyright © 2014 International Foundation for Electoral Systems. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of IFES. Requests for permission should include the following information: • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, email address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW, Fifth Floor Washington, DC 20006 Email: [email protected] Fax: 202-350-6701 Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank several IFES colleagues who provided invaluable guidance and support to the development and writing of this paper, including Rola Abdul-Latif, Safia Al-Sayaghi, Nawres Cherni, Ayesha Chugh, Nicolas Kaczorowski, Grant Kippen, Danielle Monaco, Rakesh Sharma, Evan Thomas-Arnold and Ambar Zobairi. -

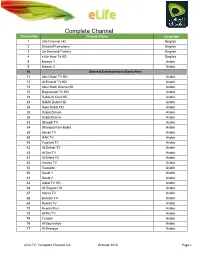

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad