Hawaiian Historical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sandokan the Tigers of Mompracem

Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem Emilio Salgari Translated by Nico Lorenzutti iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem All Rights Reserved © 2003 by Nico Lorenzutti No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permis- sion of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com SANDOKAN: The Tigers of Mompracem By Emilio Salgari Translated from the Italian by Nico Lorenzutti Edited by Dan Tidsbury Special thanks to Felice Pozzo and Claudio Gallo for their invaluable assistance in the production of this novel. Original Title: Le Tigri di Mompracem First published in serial form in “La Nuova Arena” (1883/1884) ISBN: 0-595-29133-3 Printed in the United States of America “To read is to travel without all the hassles of luggage.” Emilio Salgari (1863-1911) Contents Chapter 1: Sandokan and Yanez ......................................1 Chapter 2: Ferocity and Generosity...................................8 Chapter 3: The Cruiser...................................................16 Chapter 4: Lions and Tigers............................................20 Chapter 5: Escape and Delirium.....................................32 Chapter 6: The Pearl of Labuan ......................................38 Chapter 7: Recovery -

Sandokan: the Pirates of Malaysia

SANDOKAN The Pirates of Malaysia SANDOKAN The Pirates of Malaysia Emilio Salgari Translated by Nico Lorenzutti Sandokan: The Pirates of Malaysia By Emilio Salgari Original Title: I pirati della Malesia First published in Italian in 1896 Translated from the Italian by Nico Lorenzutti ROH Press First paperback edition Copyright © 2007 by Nico Lorenzutti All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. For information address: [email protected] Visit our website at www.rohpress.com Cover design: Nico Lorenzutti Special thanks to Felice Pozzo and Hanna Ahtonen for their invaluable advice. ISBN: 978-0-9782707-3-5 Printed in the United States of America Contents Part I: The Tiger of Malaysia Chapter 1: The Young India....................................................................1 Chapter 2: The Pirates of Malaysia .........................................................8 Chapter 3: The Tiger of Malaysia ..........................................................14 Chapter 4: Kammamuri’s Tale..............................................................21 Chapter 5: In pursuit of the Helgoland .................................................29 Chapter 6: From Mompracem to Sarawak ............................................36 Chapter 7: The Helgoland.....................................................................45 -

Prowess of Sarawak History

Prowess of Sarawak History LEE BIH NI First Edition, 2013 © Lee Bih Ni Editor: Lee Bih Ni Published by: Desktop Publisher [email protected] Translator: Lee Bih Ni Bil Content Page ________________________________________________________ Bab 1 Introduction 6 Introduction Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak Second World War and occupation Rosli Dhoby Early life Assassination of Sir Duncan George Stewart Events Death Aftermath Reburial Legacy Independence Geography Environment Demographics Population Iban people Chinese Malaysian Chinese Malay Melanau Bidayuh Orang Ulu Others Religions Demographics of Sarawak: Religions of Sarawak Government Administrative divisions Conclusion Bab 2 The White Rajahs 22 Introduction Rulers Titles Government Cession to the United Kingdom Legacy Bab 3 James Brooke, Charles Brooke & Charles Vyner Brooke 26 Early life Sarawak Burial Personal life James Brooke o Fiction o Honours o Notes Charles Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak o Biography Charles Vyner Brooke o Early life o Rajah of Sarawak o Abdication and later life o Family o Titles from birth to death Conclusion Bab 4 ROSLI DHOBI 37 Rosli Dhoby Rosli Dhoby & Sibu Who is Rosli Dhoby? Rukun 13 or Rukun Tiga Belas is a defunct Sarawakian organization that existed from 1947 until 1950. o Formation Penalty & disestablishment List of Rukun 13 members Anti-cession movement of Sarawak Factors Overview of movement Tracking Urban Struggle, Rosli Dhobi of Sibu Conclusion Bab 5 Administrative changes for self Government Sarawak -

Social Piracy in Colonial and Contemporary Southeast Asia Miles T

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2013 Social Piracy in Colonial and Contemporary Southeast Asia Miles T. Bird Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Bird, Miles T., "Social Piracy in Colonial and Contemporary Southeast Asia" (2013). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 691. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/691 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE SOCIAL PIRACY IN COLONIAL AND CONTEMPORARY SOUTHEAST ASIA SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR NIKLAS FRYKMAN AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY MILES T. BIRD FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING 2013 APRIL 29, 2013 PORTRAIT OF A PIRATE IN BRITISH MALAYA “It was a pertinent and true answer which was made to Alexander the Great by a pirate whom he had seized. When the king asked him what he meant by infesting the sea, the pirate defiantly replied: “The same as you do when you infest the whole world; but because I do it with a little ship I am called a robber, and because you do it with a great fleet, you are an emperor.” – St. Augustine1 *** Eric Hobsbawm relates confrontations between the Mesazgi brothers and the colonial Italian government in Eritrea to paint a portrait of social banditry in Bandits. The following relates the confrontation between Capt. John Dillon Northwood, a 19th-century trader based in Singapore, with Si Rahman, an Illanun pirate. This encounter illustrates the social and Hobsbawmian nature of these incidents of piracy. -

Between Frontiers: Nation and Identity in a Southeast Asian Borderland

Th e Geo-body in Transition 15 chapter one cC Th e Geo-body in Transition Spatial Turn in Southeast Asia Th e emergence of territorial states in Southeast Asia was a grandiose process of social change, marking a total transformation from the “pre-modern” to the “modern”. To understand the nature of the trans- formation, it is crucial to focus on four processes involved in the spatial turn under Western colonialism. Th e fi rst is the emergence of an ideology in the West that provided a rational for the possession of colonial space. A new and exclusive relationship between a state and a colony required an ideological basis, conceptually turning tropical territories into “no man’s land” (terra nullius). Th en through judicial declarations of land nationalization, terra nullius became an imaginary national space that had no civilized society, and vast tracts of uncultivated “waste” land fell under colo- nial governance. Th e second process required for the colonial state to realize its national space was actual policy-making with regard to the redistribu- tion of land and the marshaling of labor for cultivation of cash crops and exploitation of natural resources. Land laws, labor ordinances, and immigration acts created a social fi eld where the usufruct of land was distributed to peasants and entrepreneurs. Plural societies, where mul- tiple ethnic groups were mobilized for plantation and mining sectors are typical byproducts of colonial engineering. Th e nationalization of space and the mobilization of labor operated in tandem to make terra nullius a capitalist production site and a mercantile exchange sphere. -

Routledge Handbook of Asian Borderlands

Routledge Handbook of Asian Borderlands Edited by Alexander Horstmann, Martin Saxer, and Alessandro Rippa First published 2018 ISBN: 978-1-138-91750-7 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-68897-8 (ebk) 12 Genesis of state space Frontier commodification in Malaysian Borneo Noboru Ishikawa (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) 12 Genesis of state space Frontier commodification in Malaysian Borneo Noboru Ishikawa Introduction How is a border recognized, when spatial demarcation is not obvious, both geographically and geo- morphologically, and the state apparatus for boundary making is functionally weak? What forces, other than border control measures by the state, are at work to demarcate the line in the mental mapping of borderland peoples? To answer these questions, this chapter looks at the historical pro- cess of commodification in the borderland of western Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo as a case in point. The borderland under study has the following three characteristics. First, it has been centrally located in a web of commodity chains linking resource-rich tropics with international markets. Second, the border is inconspicuous: “altitude” and “distance” from any political center are not the crucial factors that make this borderland a distinctively nonstate space (McKinnon and Michaud 2000; Michaud 2008, 2010; Scott 2009). Third, the borderland is a space where the organizational power of the state is nominal, if not nonexistent. In the borderlands, commodification represents a process whereby value is added to products as they move across a territorial boundary. While the state attempts to generate revenue from this process, people do so illicitly. This chapter sees the genesis of the state space and boundary making within the context of long-term processes of frontier commodification, recognizing that non- timber forest produce, timber, rubber, and pepper have functioned as critical linkages connecting local society with regional and global market systems. -

3 Evading State Authority | and Secondary Sources Such As Dutch Colonial Records, Other Scholarly Literature and Oral History Collected During and After Fieldwork

3 Evading state authority The status of borders has been contingent on varying historical circum- stances, rather than being immutably rock-like. Borders shift; they leak; and they hold varying sorts of meaning for different people (Migdal 2004:5). This chapter and the subsequent Chapter 4 are a critical reading of key moments in borderland history, ranging from the latter part of the Dutch colonial period (1850s) to the end of the New Order period of former President Soeharto (1998). An underlying objective is to show the histori- cal development of the Kalimantan Iban as a border people, in particu- lar, the way the borderland, and more specifically the strategies of border inhabitants, have been shaped in relationship to colonial and postcolo- nial states and their regulative border policies. I here demonstrate that states and their borders are not static or permanent structures, separating territories and excluding people as originally intended by colonial state planners, but are the result of dynamic historical processes. The chapters unravel the continuities between these periods, describe the long-term social and economic interactions across the border, and finally discuss the implications of these historic legacies of the past for the consolidation of authority among local border elites. In order to locate the borderland in time, the historical account is di- vided into two chapters, each dealing with a specific period in borderland history (pre- and post-independence). Each period illuminates the ongo- ing ambivalent relationship between local communities and government authority (the Dutch colonial administration or the Indonesians state). The chapters argue that this ambiguity is an outcome of the particulari- ties of life at the border, of being situated between two divergent nation states and of the continuously shifting character of the border. -

SIAM and SIR JAMES BROOKE by 9\Ficholas 79Arling Universuy of Queensland B1·Isl1ane, A1tstralia

.. SIAM AND SIR JAMES BROOKE by 9\ficholas 79arling UniversUy of Queensland B1·isl1ane, A1tstralia "Sir James thoroughly understood that Eastern princes and chiefs at·e at first only influenced by fear; the fear of the consequences which might follow the neglect of the counsels of the protecting State ... " /)''ir r;'penser St. Joltn. The revolutionary impact of economic nncl social ch::mge in Southeast Asia in the nineteenth centmy was intensified by tho simnlt.aneous remodelling of its political map. 1'he frontiel'S of Sium were indeed moclitieu, and it.s old-fashioned imperial chims witlely displaced, but its economic and social history wal:! pl'ofnnndly affected by the fact that, alone ttmong South-east Asian powers, this kingrlom rettcined its political independenee. The explann.tion o:E this lies, on the one hand, in the attitude of the Siamese ruling-groups, nnd, on the other hand, in the policies of Great Britain, the predominant po\ver in the area, and a survey of Anglo-Siamese relations is essential to an understanding of modem Siam. In this survey, the mission to 13anglw1{ of Sir James Brool\e should hold a crucial place, since its failure pro duced a crisis in these relations, the prompt resolution of which re-establislwd them on a new basis and largely determined their fntnre course. 1'he conquering advance of the East India Company in India hom the late eightel'lDth centnry onwards aroused concern among the Siamese, who feared lest the ambitious Bl'itish extended their activities to the lndo.Ohincse peninsula. -

August 2006, Vol. 32 No. 3

Contents Letters: Lewis’s rifles; Plamondon’s maps; L&C $10 note 2 President’s Message: A salute to WPO and its retiring editor 6 Bicentennial Council: Thinking about the long haul 10 Eye Talk, Ear Talk 12 Sign language, translation chains, and Chinook trade jargon on the Lewis and Clark Trail By Robert R. Hunt “We eat an emensity of meat” 20 Eye talk, p. 12 How much game did the explorers consume, how many calories did they burn, and did they waste what they killed? By Kenneth C. Walcheck Lewis’s Note, Clark’s Letter 26 How the co-commanders managed to reconcile one man’s ego with the other’s own need for recognition By David Nicandri Reviews 32 Chasing Lewis and Clark across America; Rex Ziak’s foldout Columbia River guide; In Brief: Medical appendices; Nebraska guide; trail travelogue; Drouillard biography Looking Back 37 The LCTHF’s conservation roots (Part II) By Keith G. Hay L&C Roundup 39 Old Badly preserved; statues offered; For the Record Meat, p. 21 Trail Notes 40 U.S. Mint funds aid stewardship efforts On the cover As the illustration for this issue’s cover we chose Michael Haynes’s sketch of George Drouillard, the expedition’s sign-language interpreter and chief hunter, because he figures prominently in two of the three features—Robert Hunt’s “Eye Talk, Ear Talk” and Kenneth Walcheck’s “ ‘We eat an emensity of meat’,” beginning on pages 12 and 20, respectively. Drouillard is also the subject of a reissued biography by M.O. Skarsten, briefly reviewed on page 36. -

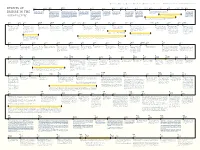

AE-Timeline I

T Tom Roberts J Jamini Roy U U Ba Nyan L Lim Cheng Hoe C Chuah Thean Teng A Awang Sitai To find out more about these artists, refer to “Six Artists' Lives and Legacies.” 1600 1757 1764 1767 1769 1770 1773 1774 1786 EVENTS OF 1577 1580 1591 1716 1775 1780 1782 1783 1784 Sir Francis Drake is the first Sir James Lancaster and George Queen Elizabeth I grants a royal charter to the newly Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar e EIC defeats Siraj-ud-daula, e EIC defeats allied In the First Anglo-Mysore James Cook, an English e EIC’s administration In the First Anglo-Maratha War against the Maratha Empire, In exchange for British Englishman to make contact with Raymond embark upon a voyage to founded East India Company (EIC) to pursue trade in establishes a decree giving the EIC the ruling Nawab of Bengal, and Mughal, Bengal and Oudh War, Mysorean forces defeat naval lieutenant, sails and of Madras and Bombay the British fail to retain any significant territorial gains in the military assistance against the Spice Islands during his the East Indies with the approval of the East Indies. e Dutch Vereenidge Oost-Indische rights to duty-free trade in India. his French allies at the Battle of forces at the Battle of Buxar. the combined armies of the maps the eastern coast of becomes subordinate to Indian subcontinent. Siam, the Sultan of Kedah EMPIRE IN THE circumnavigation of the globe. Queen Elizabeth I. Lancaster Compagnie, or United East India Company, is founded e EIC had earlier set up factories Plassey. -

Prolonged Multilingualism Among the Sebuyau: an Ethnography of Communication

Prolonged multilingualism among the Sebuyau: An ethnography of communication by Stan J. Anonby M.A. (Linguistics), University of North Dakota 1997 B.A., University of Saskatchewan 1989 B.Th., Horizon College (CPC) 1987 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Stan J. Anonby 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2020 Declaration of Committee Name: Stan J. Anonby Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Linguistics) Thesis Title: Prolonged multilingualism among the Sebuyau: An ethnography of communication Committee: Chair: Chung-hye Han Professor, Linguistics Panayiotis Pappas Supervisor Associate Professor, Linguistics John Alderete Committee Member Professor, Linguistics Donna Gerdts Committee Member Professor, Linguistics Roumiana Ilieva Internal Examiner Associate Professor, Education Lindsay Whaley External Examiner Professor Departments of Classics, Cognitive Science Program and Linguistics Program Dartmouth College ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This thesis describes the Sebuyau language and seeks to explain how this small group as maintained their culture and way of speaking in the shadow of very large languages like Malay, English and Chinese. I use the ethnographic method to study this ethnic group. Specifically, I based this ethnography of communication on two texts told by twenty-four people, who all belong to the community of practice of Keluarga Church. The study is divided into two broad areas. Part of the thesis is more synchronic linguistics, and describes the lexicon, phonology and morphology of Sebuyau. The conclusion is that Sebuyau is a variety of Iban. The lexicon exhibits considerable borrowing from languages that are no longer spoken in the area – such as Sanskrit. -

"So Strange, Novel and Fascinating": Margaret Brooke, Ranee of Sarawak

Volume 22, number 1, May 1995 Cassandra Pybus "SO STRANGE, NOVEL AND FASCINATING": MARGARET BROOKE, RANEE OF SARAWAK. They mounted the landing stage at Kuching with great fanfare, the Rajah leading a procession through the bazaar under the traditional yellow satin umbrella carried by the ancient Subu, Umbrella Bearer and Executioner to the State of Sarawak. Carrying the umbrella was Subu's only task, as there was no call for executions in the Brooke Raj. Excitement rose as the party stepped onto the green barge presented to the first Rajah, Sir James Brooke (1803-68), by the King of Siam, to be carried to the river mouth where the Rajah's yacht lay at anchor. It was September 1873. The present Rajah, Charles Brooke, and his young Ranee, Margaret, were making their first return visit to England with their children, a girl, Ghita, aged two and a half, and twin baby boys, James and Charles. The omens had been good for their departure, dispelling the mut- tering in the bazaar and kampong that twins were unlucky, especially since two months before their birth there had been an eclipse of the sun. Nothing, however, could dispel the unease caused by the new English nurse, who was seen to be cross-eyed. Later it became known that the native amah had stolen and brought on board some small idol, and, so it was said, put a curse on the Ranee and her family. Before boarding the P&O liner for London the Rajah and Ranee had been feted in Singapore, and had managed to get the children photographed despite a raging cholera epidemic.