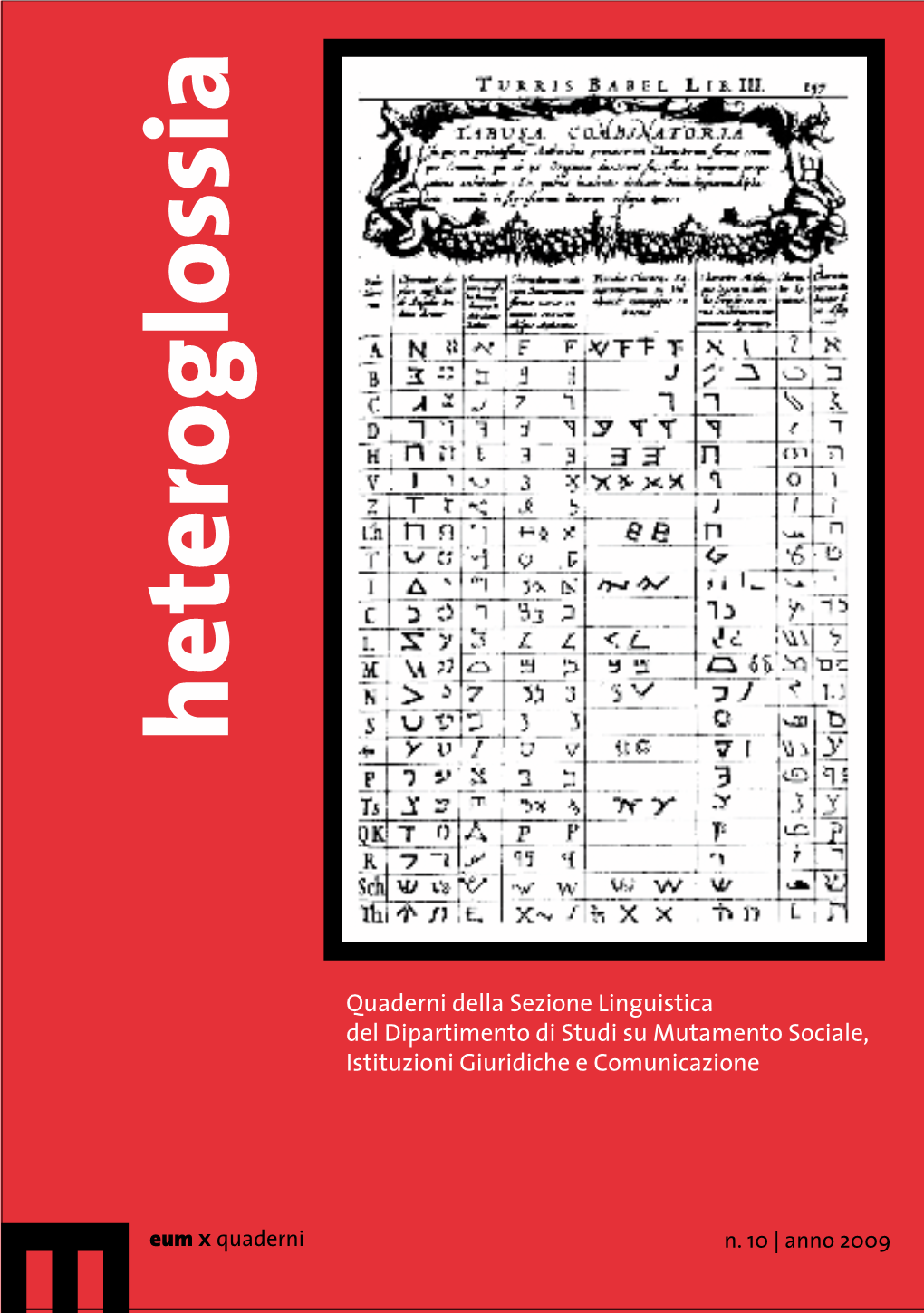

Heteroglossia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

Sandokan the Tigers of Mompracem

Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem Emilio Salgari Translated by Nico Lorenzutti iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem All Rights Reserved © 2003 by Nico Lorenzutti No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permis- sion of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com SANDOKAN: The Tigers of Mompracem By Emilio Salgari Translated from the Italian by Nico Lorenzutti Edited by Dan Tidsbury Special thanks to Felice Pozzo and Claudio Gallo for their invaluable assistance in the production of this novel. Original Title: Le Tigri di Mompracem First published in serial form in “La Nuova Arena” (1883/1884) ISBN: 0-595-29133-3 Printed in the United States of America “To read is to travel without all the hassles of luggage.” Emilio Salgari (1863-1911) Contents Chapter 1: Sandokan and Yanez ......................................1 Chapter 2: Ferocity and Generosity...................................8 Chapter 3: The Cruiser...................................................16 Chapter 4: Lions and Tigers............................................20 Chapter 5: Escape and Delirium.....................................32 Chapter 6: The Pearl of Labuan ......................................38 Chapter 7: Recovery -

Line Producer

0 INDEX Pag. 2 - DIRECTOR’S NOTE Pag. 4 - SINOPSYS Pag. 5 - TECNICAL DATA Pag. 6 - PRODUCTION PROFILE Pag. 7 - DIRECTOR Pag. 11 - SCREENWRITER Pag. 12 - CAST WISH LIST Pag. 15 - LOCATIONS Pag. 18 - SKETCHES GOLETTA AND PRAHO 1 DIRECTOR’S NOTE Many years have passed since the last Theatrical or Television production narrating the achievements of the most fascinating and exotic hero born from the imagination of a novelist and this is where our story starts, from the casual meeting between the young Emilio Salgari in a tavern at the port of Trieste and a mysterious sailor who will tell him a story, a story rich of adventure and courage, of battles and love : the story of the Tiger of Mompracem. The old sailor is Yanez De Gomera, a Portuguese pirate and Sandokan’s companion in many adventures. The idea to narrate Salgari’s character at the beginning and at the end of the story, will also give a hypothetical reading of a mystery that has always intrigued thousands of readers worldwide: how Emilio Salgari was able to describe so well and with such abundance of exciting details, lands and countries that in reality he had never seen, having never been able to travel if not with his imagination. Another innovation in comparison to the previous versions of Sandokan will be the story of the genesis of the character, the creation of its myth by the English themselves, that he will fight against for his whole life. In fact we will narrate Sandokan as a child, son of a Malayan Rajah who fights against the control of his country by the English and for this reason he is killed together with all his family by some hired assassins Dayakis paid by James Brooke the white rajah of Sarawak, a man without scruples at the service of the Crown. -

Sandokan: the Pirates of Malaysia

SANDOKAN The Pirates of Malaysia SANDOKAN The Pirates of Malaysia Emilio Salgari Translated by Nico Lorenzutti Sandokan: The Pirates of Malaysia By Emilio Salgari Original Title: I pirati della Malesia First published in Italian in 1896 Translated from the Italian by Nico Lorenzutti ROH Press First paperback edition Copyright © 2007 by Nico Lorenzutti All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. For information address: [email protected] Visit our website at www.rohpress.com Cover design: Nico Lorenzutti Special thanks to Felice Pozzo and Hanna Ahtonen for their invaluable advice. ISBN: 978-0-9782707-3-5 Printed in the United States of America Contents Part I: The Tiger of Malaysia Chapter 1: The Young India....................................................................1 Chapter 2: The Pirates of Malaysia .........................................................8 Chapter 3: The Tiger of Malaysia ..........................................................14 Chapter 4: Kammamuri’s Tale..............................................................21 Chapter 5: In pursuit of the Helgoland .................................................29 Chapter 6: From Mompracem to Sarawak ............................................36 Chapter 7: The Helgoland.....................................................................45 -

Of ODOARDOBECCARI Dedication

1864 1906 1918 Dedicated to the memory of ODOARDOBECCARI Dedication A dedication to ODOARDO BECCARI, the greatest botanist ever to study in Malesia, is long overdue. Although best known as a plant taxonomist, his versatile genius extended far beyond the basic field ofthis branch ofBotany, his wide interest leading him to investigate the laws ofevolution, the interrelations between plants and animals, the connection between vegetation and environ- cultivated ment, plant distribution, the and useful plants of Malesia and many other problems of life. plant But, even if he devoted his studies to plants, in the depth of his mind he was primarily a naturalist, and in his long, lonely and dangerousexplorations in Malesia he was attracted to all aspects ofnature and human life, assembling, besides plants, an incredibly large number of collec- tions and an invaluable wealth ofdrawings and observations in zoology, anthropologyand ethnol- He ogy. was indeed a naturalist, and one of the greatest of his time; but never in his mind were the knowledge and beauty of Nature disjoined, and, as he was a true and complete naturalist, he the time was at same a poet and an artist. His Nelleforestedi Borneo, Viaggi ericerche di un mturalista(1902), excellently translatedinto English (in a somewhatabbreviated form) by Prof. E. GioLiouandrevised and edited by F.H.H. Guillemardas Wanderingsin the great forests of Borneo (1904), is a treasure in tropical botany; it is in fact an unrivalledintroductionto tropical plant lifeand animals, man included. It is a most readable book touching on all sorts of topics and we advise it to be studied by all young people whose ambition it is to devote their life to tropical research. -

An Early History of Vireya the People, Places & Plants of the Nineteenth Century

An Early History of Vireya The People, Places & Plants of the Nineteenth Century Chris Callard The distribution of Rhododendron subgenus Vireya is centred on the botanical region known as Malesia – an area of south-east Asia encompassing the Malay Archipelago, the Philippines, Borneo, Indonesia and New Guinea and surrounding island groups. It is for this reason that vireyas have sometimes in the past been referred to as ‘Malesian Rhododendrons’, although nowadays this is not considered a strictly accurate term as a small number of the 318 species in subgenus Vireya grow outside this region and, similarly, a few species from other subgenera of Rhododendron are also to be found within its boundaries. Broadly speaking, the Vireya group extends from Taiwan in the north to Queensland, Australia in the south, and from India in the west to the Solomon Islands in the east. Much of the early recorded history of the plants of Rhododendron subgenus Vireya came about as a result of the activities of European nations, particularly Britain and Holland, pursuing their colonial ambitions across the Malay Archipelago and, later, east to New Guinea. As their Empires expanded into these previously unexplored territories, settlements were established and expeditions mounted to survey the natural wealth and geography of the land. Many of these early explorers had scientific backgrounds, although not always in botany, and collected all manner of exotic flora and fauna found in these unfamiliar surroundings, to ship back to their homelands. The Vireya story starts in June 1821 when the Scotsman, William Jack, one of “a party of gentlemen”i, set out from Bencoolen (now Bengkulu), a settlement on the south-west coast of Sumatra, to reach the summit of Gunong Benko (Bungkuk), the so-called Sugar Loaf Mountain, “not estimated to exceed 3,000 feet in height”. -

Honour List 2012 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2012

HONOUR LIST 2012 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2012 IBBY Secretariat Nonnenweg 12, Postfach CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland Tel. [int. +4161] 272 29 17 Fax [int. +4161] 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ibby.org Book selection and documentation: IBBY National Sections Editors: Liz Page and Luzmaria Stauffenegger Design and Cover: VischerVettiger, Basel Printing: Cerdik Publications, Malaysia www.ijb.de Cover illustration: Motifs from nominated books (Nos. 41, 46, 51, 67, 78, 83, 96, 101, 106, 108, 111, 134 ) We wish to kindly thank the Internation- al Youth Library, Munich for their help with the Bibliographic data and subject headings, and Cerdik Publications for their generous sponsoring of the printing of this catalogue. IBBY Honour List 2012 1 IBBY Honour List 2012 The IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of outstanding, recently published books, honour- ing writers, illustrators and translators from IBBY member countries. The first Honour List in 1956 was a selection of 15 entries from 12 countries. For the 2012 Honour List, 58 countries have sent 169 nominations in 44 different languages. Selected for the 2012 list are 65 entries in the category of Writing; 54 in the category Illustration; and 50 in the category Translation. Included for the first time is a book in Ojibwe from Canada, as well as two titles in Khmer from Cambodia and three new books on Arabic from the United Arab Emirates. This steady increase demonstrates the growth of IBBY and the continuing efforts to share good books across the world. The titles are selected by the National Sections of IBBY, who are invited to nominate books charac- teristic of their country and suitable to recommend for publication in different languages. -

Odoardo Beccari: La Vita Odoardo Beccari: His Life

sc H E D A D I A pp RO F ONDI M ENTO · In SI G H T Odoardo Beccari: la vita Odoardo Beccari: his life asce a Firenze il 16 novembre 1843 (Fig. 9) e, dopo essere Nrimasto orfano di entrambi i genitori in tenera età, viene affidato allo zio materno che vive a Lucca. Qui frequenta le scuole e, appena tredicenne, fa le prime raccolte di piante co- minciando ad interessarsi alla Botanica sotto la guida dei suoi insegnanti, l’abate Ignazio Mezzetti e Cesare Bicchi, allora Di- rettore dell’Orto Botanico di quella città. Si iscrive alla Facoltà di Scienze Naturali dell’Università di Pisa e durante gli studi kinizia ad occuparsi di crittogame, tanto da diventare un contri- butore, con le sue raccolte, della nota Serie Erbario Crittogami- co Italiano (cfr. Fig. 4, p. 203). Per incomprensioni con un suo docente, il famoso Pietro Savi, di cui era divenuto nel frattempo assistente, finisce per laurearsi a Bologna con Antonio Berto- loni nel 1864. A Bologna conosce anche il marchese Giacomo Doria, naturalista e futuro fondatore del Museo Civico di Sto- ria Naturale di Genova, con il quale decide, appena laureato, di compiere l’esplorazione del lontano Ragiato di Sarawak, in Borneo. Una volta terminati gli accurati preparativi della spe- dizione, compreso anche un soggiorno negli Erbari di Kew e del British Museum di Londra per esaminarne le raccolte della Malesia e dove ha la fortuna di conoscere grandi botanici, come gli Hooker, padre e figlio, e J. Ball, nonché C. Darwin, Beccari, non ancora ventiduenne, parte per la prima di quelle esplora- zioni nel sud-est asiatico che lo renderanno famoso in tutto il mondo. -

Prowess of Sarawak History

Prowess of Sarawak History LEE BIH NI First Edition, 2013 © Lee Bih Ni Editor: Lee Bih Ni Published by: Desktop Publisher [email protected] Translator: Lee Bih Ni Bil Content Page ________________________________________________________ Bab 1 Introduction 6 Introduction Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak Second World War and occupation Rosli Dhoby Early life Assassination of Sir Duncan George Stewart Events Death Aftermath Reburial Legacy Independence Geography Environment Demographics Population Iban people Chinese Malaysian Chinese Malay Melanau Bidayuh Orang Ulu Others Religions Demographics of Sarawak: Religions of Sarawak Government Administrative divisions Conclusion Bab 2 The White Rajahs 22 Introduction Rulers Titles Government Cession to the United Kingdom Legacy Bab 3 James Brooke, Charles Brooke & Charles Vyner Brooke 26 Early life Sarawak Burial Personal life James Brooke o Fiction o Honours o Notes Charles Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak o Biography Charles Vyner Brooke o Early life o Rajah of Sarawak o Abdication and later life o Family o Titles from birth to death Conclusion Bab 4 ROSLI DHOBI 37 Rosli Dhoby Rosli Dhoby & Sibu Who is Rosli Dhoby? Rukun 13 or Rukun Tiga Belas is a defunct Sarawakian organization that existed from 1947 until 1950. o Formation Penalty & disestablishment List of Rukun 13 members Anti-cession movement of Sarawak Factors Overview of movement Tracking Urban Struggle, Rosli Dhobi of Sibu Conclusion Bab 5 Administrative changes for self Government Sarawak -

SANDOKAN (Formerly Known As - the Black Sea of Sandokan)

Transformers Timelines Presents: THE DARK HEART OF SANDOKAN (formerly known as - The Black Sea of Sandokan) by Benson Yee Art by Jake Isenberg and Thomas Deer (Please check out Issue #13 of the Hasbro Transformers Collectors’ Club Magazine for the PROLOGUE to this story.) CHAPTER ONE The inky blackness of space was pierced by the fluid form of the Decepticon pirate ship Kalis’ Lament. Shaped like a gigantic cephalopod, the vessel did not push through space so much as it glided. Its silent movement through space was reflected on its bridge, where its crew attended to their duties in silence and complete, utter boredom. Alarms suddenly brought the crew out of their near catatonic state. The ship’s resident scientist, Brushguard was the first to report. “One of our probes is returning. I’m downloading its logs now.” The ship’s first officer, Skywarp nodded. “Put it up on the screen.” he said, eager to see what was in the probe’s logs. The Lament’s probes were periodically dispatched to nearby solar systems to locate possible targets to plunder for riches and resources. Often they returned with very little worth pursuing, but now and then they would find targets ripe for the taking. That fact alone made every probe’s return an exciting event. The probe’s log began to play back on the screen. Every member of the crew looked at the main view screen. It played a recording of the attack on the Star Arrow along with several power level readings from the ship. A more invasive scan brought up an image of the Force Chip on the screen. -

Hawaiian Historical Society

HAWAIIAN COLLECTION 116.UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY SIXTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1959 SIXTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR 1959 HONOLULU, HAWAII PUBLISHED, I960 The scope of the Hawaiian Historical Society as specified in its charter is "the collection, study, preservation and publication of all material pertaining to the history of Hawaii, Polynesia and the Pacific area." No part of this report may be reprinted unless credit is given to its author and to the Hawaiian Historical Society. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA THE ADVERTISER PUBLISHING CO., LTD., HONOLULU DU620 1959 cor>o? CONTENTS PAGE Officers and Committees for 1959 4 Officers and Committees for I960 5 The Filibuster of Walter Murray Gibson 7 The Madras Affair 33 Minutes of the 68th Annual Meeting 46 Meeting of November 19, 1959 47 Report of the President 48 Report of the Auditor 49 Statement of Financial Condition (Exhibit A) 50 Statement of Income and Expense (Exhibit B) 51 Report of the Librarian 52 List of Members 55 HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1959 President WILLIAM R. NORWOOD Vice President SIMEST.HOYT treasurer JACOB ADLER Recording Secretary AGNES C. CONRAD Corresponding Secretary and Librarian . MRS. WILLOWDEAN C. HANDY TRUSTEES THROUGH 1959 TRUSTEES THROUGH I960 Agnes C. Conrad Charles H. Hunter Simes T. Hoyt Janet E. Bell Bernice Judd Meiric K. Dutton Roswell M. Towill Donald D. Mitchell Auditor MRS. VIVIEN K. GILBERT, CP. A. COMMITTEES FOR 1959 FINANCE COMMITTEE Roswell M. Towill, Chairman Jacob Adler Simes T. Hoyt Vivien K. Gilbert EDITORIAL AND PRINTING COMMITTEE Meiric K. -

Italy's Enduring Love Affair with Emilio Salgari

Prospero Still telling tales Italy’s enduring love affair with Emilio Salgari A century after his death, the author and his creations still occupy a prominent place in the cultural imagination Prospero Jun 19th 2017 | by A.V. LAST month, Neapolitan anti-mafia investigators announced plans to indict Francesco “Sandokan” Schiavone, a local gangster, for the killing of a policeman in 1989. Naples has long been used to Mr Schiavone and his ilk: he is already in jail for murder, along with dozens of his colleagues. What distinguishes Mr Schiavone is his nickname. “Sandokan” was first conjured by Emilio Salgari, a writer who died over a century ago. That his most famous character is still considered relevant hints at his influence. WelcoXme to The Born in Verona in 1862, Salgari led a sad and quietly dramatic life. Although he was Economist. prodigious—writing more than 200 novels and stories in his short life—and Subscribe popular, Salgari struggled with poverty. He was also crippled by personal tragedy: today his wife was sent to an asylum, and his father committed suicide. Salgari to take advantage eventually took his own life, disembowelling himself in the style of a Japanese of our samurai. “You have kept me and my family in semi-penury,” he wrote to his introductory publisher. “I salute you as I break my pen.” offers and Far removed from his bleak personal enjoy Latest updates circumstances, Salgari’s stories pant with 12 How Poland’s government is weakening life. He never travelled far, but deployed his weeks' democracy access THE ECONOMIST EXPLAINS frantic imagination to render faraway A chance finding may lead to a treatment for places like the American West or the golden multiple sclerosis SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY beaches of the Caribbean.