The Excursion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

Sandokan the Tigers of Mompracem

Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem Emilio Salgari Translated by Nico Lorenzutti iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Sandokan The Tigers of Mompracem All Rights Reserved © 2003 by Nico Lorenzutti No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permis- sion of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com SANDOKAN: The Tigers of Mompracem By Emilio Salgari Translated from the Italian by Nico Lorenzutti Edited by Dan Tidsbury Special thanks to Felice Pozzo and Claudio Gallo for their invaluable assistance in the production of this novel. Original Title: Le Tigri di Mompracem First published in serial form in “La Nuova Arena” (1883/1884) ISBN: 0-595-29133-3 Printed in the United States of America “To read is to travel without all the hassles of luggage.” Emilio Salgari (1863-1911) Contents Chapter 1: Sandokan and Yanez ......................................1 Chapter 2: Ferocity and Generosity...................................8 Chapter 3: The Cruiser...................................................16 Chapter 4: Lions and Tigers............................................20 Chapter 5: Escape and Delirium.....................................32 Chapter 6: The Pearl of Labuan ......................................38 Chapter 7: Recovery -

Fedel E Costante

CORO The Sixteen Edition CORO live The Sixteen Edition Other Sixteen Edition recordings available on CORO Heroes and Heroines cor16025 Delirio Amoroso cor16030 Sarah Connolly - Handel arias Ann Murray - Handel Italian secular cantatas Harry Christophers Harry Christophers The Symphony of The Symphony of Harmony & Invention Harmony & Invention "Connolly seals her "...a dazzling revelation... reputation as our best Ann Murray sings Handel mezzo in many superlatively." years." bbc music magazine financial times Vivaldi: Gloria in D Allegri - Miserere cor16014 Fedel e Costante Bach: Magnificat in D cor16042 & Palestrina: Missa Papae Marcelli, Stabat Mater Russell, Fisher, Lotti: Crucifixus Browner, Partridge, "Christophers draws HANDEL ITALIAN CANTATAS George brilliant performances from "Singing and playing his singers, both technically on the highest level." assured and vividly Elin Manahan Thomas bbc music magazine impassioned." the guardian Principals from The Symphony To find out more about The Sixteen, concert tours, and to buy CDs, visit www.thesixteen.com cor16045 of Harmony and Invention There are many things about The Sixteen her unique amongst her peers. This live elcome to the world of four that make me very proud, above all the recital of Handel Italian Cantatas was part of women, all of whom have nurturing of future talent. Over the years, the 2006 Handel in Oxford Festival. Those Wbeen betrayed by love and its we have produced some outstanding who were actually present at that concert deceitful charms, to varying degrees and performers; among them are Carolyn were witness to a performance of captivating for numerous reasons. Sampson, Sarah Connolly, Mark Padmore, communication and sparkling intelligence. Agrippina condotta a morire pretends Christopher Purves and Jeremy White. -

11Th Grade English Worksheet Bundle: Volume Two Printable English Worksheets from Edmentum's Study Island

11th Grade English Worksheet Bundle: Volume Two Printable English worksheets from Edmentum's Study Island. Grade 11 English: Summary What’s so special about a bunch of green beans called edamame? It’s not just the name, but also the contents that make this seed a favorite among Japanese and Chinese people. Edamame is a fancy name coined for boiled soybeans. We all know how healthy and nutritious soybeans are. Eating half a cup of these tasty beans punches up the intake of protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals in a diet. An interviewer once saw Faith Hill snacking on edamame at an interview for Country Music Television. Soy is known to promote good health and prevent certain diseases. A recent study shows that soy helps reduce insulin resistance, kidney damage, and increases good cholesterol. Soy products have components that fight cancer. Isoflavone is the most active anti-cancer element in soy products. Studies show that consuming 100-200 milligrams of isoflavone a day can lower the risk of cancer. 1. What is a good summary of paragraph 2? A. Japanese and Chinese are the only people known to eat soy-based products. B. Since soy products are beneficial for one's health, celebrities eat them very regularly. C. Soy products contain isoflavone. This anti-cancer element can help reduce the risk of cancer. D. Soy is rich in vitamins and minerals. It contains a lot of proteins, vitamins, and fiber. 2. What sentence best summarizes the above selection? A. After an interviewer saw Faith Hill snacking on edamame, the bean became famous among people. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Hett-Syll-80020-19

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York History Department Hist 80200 Literature of Modern Europe II Thursdays 4:15-6:15 GC 3310A Prof. Benjamin Hett e-mail [email protected] GC office 5404 Office hours Thursdays 2:00-4:00 or by appointment Course Description: This course is intended to provide an introduction to the major themes and historians’ debates on modern European history from the 18th century to the present. We will study a wide range of literature, from what we might call classic historiography to innovative recent work; themes will range from state building and imperialism to war and genocide to culture and sexuality. After completing the course students should have a solid basic grounding in the literature of modern Europe, which will serve as a basis for preparation for oral exams as well as for later teaching and research work. Requirements: In a small seminar class of this nature effective class participation by all students is essential. Students will be expected to take the lead in class discussions: each week one student will have the job of introducing the literature for the week and to bring to class questions for discussion. Over the semester students will write a substantial historiographical paper (approximately 20 pages or 6000 words) on a subject chosen in consultation with me, due on the last day of class, May 13. The paper should deal with a question that is controversial among historians. Students must also submit two short response papers (2-3 pages) on readings for two of the weekly sessions of the course, and I will ask for annotated bibliographies for your historiographical papers on March 28. -

Antonio Salieri Stefanie Attinger, Krüger & Ko

Aufnahme / Recording: World Premiere Recordings 28./29.1.07; 29./30.9.07; 28./29.10.07 Gesellschaftshaus Heidelberg, Pfaffengrund Toningenieur und Schnitt / Sound engineer and editing: Eckhard Steiger, Tonstudio van Geest, Sandhausen Musikalischer Berater und Einführungstext / Music consultant and critical editions: Timo Jouko Herrmann English Translation: Für weitere Informationen / For further information: Dr. Miguel Carazo & Association Mannheimer Mozartorchester - Tourneebüro Foto / Photo: Classic arts gmbh · Bergstr. 31 · D-69120 Heidelberg Rosa-Frank.com Tel.: +49-(0) 6221-40 40 16 · Fax: +49-(0) 6221-40 40 17 Grafik / Coverdesign: [email protected] · www.mannheimer-mozartorchester.de Antonio Salieri Stefanie Attinger, Krüger & Ko. Vol. 1 & 2007 hänssler CLASSIC, D-71087 Holzgerlingen Ouvertüren & Ballettmusik Mit freundlicher Unterstützung von Prof. Dr. Dietrich Götze, Heidelberg Overtures & Ballet music Außerdem erschienen / Also available: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Symphony No. 1 C Minor op. 11 / String Symphony No. 8 (Version with winds) / String Symphony No. 13 (Symphonic Movement) Heidelberger Sinfoniker / Thomas Fey CD-No. 98.275 Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Symphony No. 4 „Italian“ / String Symphonies Nos. 7 & 12 Heidelberger Sinfoniker / Thomas Fey CD-No. 98.281 Eine große Auswahl von über 700 Klassik-CDs und DVDs finden Sie bei hänssler CLASSIC unter www.haenssler-classic.de, auch mit Hörbeispielen, Downloadmöglichkeiten und Künstlerinformationen. Gerne können Sie auch unseren Gesamtkatalog anfordern Mannheimer Mozartorchester unter der Bestellnummer 955.410. E-Mail-Kontakt: [email protected] Thomas Fey Enjoy a huge selection of more than 700 classical CDs and DVDs from hänssler CLASSIC at www.haenssler-classic.com, including listening samples, download and artist related information. You may as well order our printed catalogue, order no.: 955.410. -

Memoirs of a Geisha Arthur Golden Chapter One Suppose That You and I Were Sitting in a Quiet Room Overlooking a Gar-1 Den, Chatt

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html Memoirs Of A Geisha Arthur Golden Chapter one Suppose that you and I were sitting in a quiet room overlooking a gar-1 den, chatting and sipping at our cups of green tea while we talked J about something that had happened a long while ago, and I said to you, "That afternoon when I met so-and-so . was the very best afternoon of my life, and also the very worst afternoon." I expect you might put down your teacup and say, "Well, now, which was it? Was it the best or the worst? Because it can't possibly have been both!" Ordinarily I'd have to laugh at myself and agree with you. But the truth is that the afternoon when I met Mr. Tanaka Ichiro really was the best and the worst of my life. He seemed so fascinating to me, even the fish smell on his hands was a kind of perfume. If I had never known him, I'm sure I would not have become a geisha. I wasn't born and raised to be a Kyoto geisha. I wasn't even born in Kyoto. I'm a fisherman's daughter from a little town called Yoroido on the Sea of Japan. In all my life I've never told more than a handful of people anything at all about Yoroido, or about the house in which I grew up, or about my mother and father, or my older sister-and certainly not about how I became a geisha, or what it was like to be one. -

Sandokan: the Pirates of Malaysia

SANDOKAN The Pirates of Malaysia SANDOKAN The Pirates of Malaysia Emilio Salgari Translated by Nico Lorenzutti Sandokan: The Pirates of Malaysia By Emilio Salgari Original Title: I pirati della Malesia First published in Italian in 1896 Translated from the Italian by Nico Lorenzutti ROH Press First paperback edition Copyright © 2007 by Nico Lorenzutti All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. For information address: [email protected] Visit our website at www.rohpress.com Cover design: Nico Lorenzutti Special thanks to Felice Pozzo and Hanna Ahtonen for their invaluable advice. ISBN: 978-0-9782707-3-5 Printed in the United States of America Contents Part I: The Tiger of Malaysia Chapter 1: The Young India....................................................................1 Chapter 2: The Pirates of Malaysia .........................................................8 Chapter 3: The Tiger of Malaysia ..........................................................14 Chapter 4: Kammamuri’s Tale..............................................................21 Chapter 5: In pursuit of the Helgoland .................................................29 Chapter 6: From Mompracem to Sarawak ............................................36 Chapter 7: The Helgoland.....................................................................45 -

Curriculum Vitae (Updated August 1, 2021)

DAVID A. BELL SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS PROFESSOR IN THE ERA OF NORTH ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Curriculum Vitae (updated August 1, 2021) Department of History Phone: (609) 258-4159 129 Dickinson Hall [email protected] Princeton University www.davidavrombell.com Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 @DavidAvromBell EMPLOYMENT Princeton University, Director, Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies (2020-24). Princeton University, Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, Department of History (2010- ). Associated appointment in the Department of French and Italian. Johns Hopkins University, Dean of Faculty, School of Arts & Sciences (2007-10). Responsibilities included: Oversight of faculty hiring, promotion, and other employment matters; initiatives related to faculty development, and to teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences; chairing a university-wide working group for the Johns Hopkins 2008 Strategic Plan. Johns Hopkins University, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities (2005-10). Principal appointment in Department of History, with joint appointment in German and Romance Languages and Literatures. Johns Hopkins University. Professor of History (2000-5). Johns Hopkins University. Associate Professor of History (1996-2000). Yale University. Assistant Professor of History (1991-96). Yale University. Lecturer in History (1990-91). The New Republic (Washington, DC). Magazine reporter (1984-85). VISITING POSITIONS École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Visiting Professor (June, 2018) Tokyo University, Visiting Fellow (June, 2017). École Normale Supérieure (Paris), Visiting Professor (March, 2005). David A. Bell, page 1 EDUCATION Princeton University. Ph.D. in History, 1991. Thesis advisor: Prof. Robert Darnton. Thesis title: "Lawyers and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Paris (1700-1790)." Princeton University. -

First Place Flash Fiction, Grades 7-8 Lily Wissler the Ten O'clock News

First Place Flash Fiction, Grades 7-8 Lily Wissler The Ten O’clock News Jane Matthers felt her traitorous lips lift into a smile, though she did not let it drop right away. Swishing around the remainder of the drink in front of her, Jane was leaning on her elbows, balancing on the edge of her bar stool. She was antsy for something, though she would never admit to what it was. That was a secret she’d take with her to the grave. If the undisclosed were an object, she would carry it between her painstakingly sanitized hands and clutch it in front of her carefully chosen cardigan. Jane had been a cautious child. Picking and pulling apart her every movement. Her words had always been so premeditated that she often found herself saying things that belonged to future conversations. The quality showed now as she shushed her hiccupy-giggles with an ease that had been practiced for years. Jane recounted the evening’s events. The screams played over in her head like her own personal soundtrack. She had felt comfort in the stabbing and slashing. There was neatness to it like a freshly printed dictionary. Jane wasn’t as careful to withhold her giggles this time. She felt wise. She had taken care of everything, tied every loose end. What she hadn’t accounted for was the mess. Jane had to burn the cashmere sweater, but it was worth it. After the first spike of adrenaline, she knew it was worth it. With restless limbs, and soaring spirits, Jane watched the TVs before her. -

Programme19may.Pdf

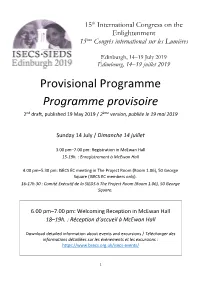

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h.