The Diaconate Renewed: Service, Word and Worship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2018 Issue

Saskatchewan anglican The newspaper of the Dioceses of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon and Qu’Appelle • A Section of the Anglican Journal • November 2018 www.facebook.com/thesaskatchewananglican — www.issuu.com/thesaskatchewananglican Lest we forget "Though an army besiege me, my heart will not fear; though war to seek him in his temple" (Psalm 27: 3-4, NIV). This grave of an un- break out against me, even then I will be confident. One thing I ask known First World War French soldier is one of many in a common- from the Lord, this only do I seek: that I may dwell in the house of wealth war graves cemetery at the Thiepval Memorial in northern the Lord all the days of my life, to gaze on the beauty of the Lord and France near the city of Amiens. Photo by Jason G. Antonio 2 The Saskatchewan Anglican November 2018 Clergy and laity Internships are opportunity together provide important support struc- tures for students to learn, for personal, parish growth while the interns deeply appreciate the investment of time and energy on their By the Rev. were a student, someone behalf. Published by the Dr. Iain Luke might drop you off in town On the other hand, Dioceses of Saskatchewan, Principal, College of in April, and pick you parishes receive benefits Saskatoon and Qu’Appelle. Emmanuel & St. Chad up in September, but in too. Having an inquisitive Published monthly between you were on your set of eyes join your except for July and August. ast month’s column own! church for a season is a identified the Students had to act the great way to learn more Whole No. -

The Companion to the 2015 Edington Music Festival

The Companion to THE EDINGTON MUSIC FESTIVAL A festival of music within the liturgy 23-30 AUGUST 2015 The PRioRy ChuRch of Saint MaRy, Saint KathaRine and All SaintS Edington, WeStbuRy, WiltShiRe THE COM PANION TO THE ED I NGTON MUSIC FESTI VAL Sunday 23 to Sunday 30 AuguSt 2015 Contents Introduction Benjamin Nicholas IntRoduction page 3 FoR Some, the fiRSt Edington MuSic FeStival in AuguSt 1956 iS Still within FeStival and geneRal infoRmation page 6 living memoRy, and it haS been wondeRful to heaR fRom Some of the SingeRS FeStival paRticipantS page 10 who weRe involved in that veRy fiRSt feStival. WhilSt the woRld outSide iS veRy, ORdeRS of SeRvice, textS and tRanSlationS page 12 veRy diffeRent, the puRpoSe of thiS unique week RemainS veRy much the Same: David TRendell page 48 a feStival of muSic within the lituRgy Sung by SingeRS fRom the fineSt CathedRal SiR David & Lady BaRbaRa Calcutt page 50 and collegiate choiRS in the land. It iS veRy good to welcome you to the Sixty yeaRS of Edington page 52 Diamond Jubilee FeStival. The Edington MuSic FeStival—commiSSioned woRkS page 54 TheRe haS been plenty to celebRate in Recent feStivalS, and the dedication of BiogRaphieS page 56 the new HaRRiSon & HaRRiSon oRgan laSt yeaR iS Still veRy much in ouR mindS. FeStival PaRticipantS fRom 1956 page 59 It may be no SuRpRiSe that the theme thiS yeaR iS inSpiRed by a cycle of oRgan woRkS by the oRganiSt-compoSeR Jean-LouiS FloRentz. The Seven movementS of hiS Suite LaUdes have influenced the StRuctuRe of the week: A call to prayer , Incantation , Sacred dance , Meditation , Sacred song , Procession and Hymn . -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Cni May 4,2021

May 4, 2021 Image of the day - St. Macartin’s, Enniskillen [email protected] Page 1 May 4, 2021 St. Macartin’s to receive £25,000 funding for repair work A much-loved Fermanagh church is to share in a £611,000 funding payout from the National Churches Trust, Victoria Johnston writes in the Impartial Reporter. A £25,000 grant will help fund urgent roof and stonework repairs and help safeguard the heritage of St Macartin’s Cathedral and enable the church to continue to serve the local community. Critical role Funding for the grant comes from the Department for Communities Historic Environment Division’s Covid-19 Culture, Languages, Arts and Heritage Support Programme. Communities Minister Deirdre Hargey said: “I am delighted that I have been able to provide this support. This will help catalyse renewal activity and animate communities affected by Covid-19 by working with them to tackle the issues faced by our historic church buildings which at the heart of our communities. Repairs “Churches have played a critical role in the Covid-19 response and it is fitting that they now become part of our renewal through increased focus on conservation- led repair of heritage fabric, together with provision of new facilities to help ensure their continued use into the future.” [email protected] Page 2 May 4, 2021 Broadcaster and journalist Huw Edwards, Vice President of The National Churches Trust, said: “I’m delighted that St Macartin’s Cathedral, Enniskillen is being helped with a £25,000 grant from the National Churches Trust thanks to the support of the Department of Communities in Northern Ireland. -

General Synod

GS 1708-09Y GENERAL SYNOD DRAFT BISHOPS AND PRIESTS (CONSECRATION AND ORDINATION OF WOMEN) MEASURE DRAFT AMENDING CANON No. 30 ILLUSTRATIVE DRAFT CODE OF PRACTICE REVISION COMMITTEE Chair: The Ven Clive Mansell (Rochester) Ex officio members (Steering Committee): The Rt Revd Nigel McCulloch, (Bishop of Manchester) (Chair) The Very Revd Vivienne Faull (Dean of Leicester) Dr Paula Gooder (Birmingham) The Ven Ian Jagger (Durham) (from 26 September 2009) The Ven Alastair Magowan (Salisbury) (until 25 September 2009) The Revd Canon Anne Stevens (Southwark) Mrs Margaret Swinson (Liverpool) Mr Geoffrey Tattersall QC (Manchester) The Rt Revd Trevor Willmott (Bishop of Dover) Appointed members: Mrs April Alexander (Southwark) Mrs Lorna Ashworth (Chichester) The Revd Dr Jonathan Baker (Oxford) The Rt Revd Pete Broadbent (Southern Suffragans) The Ven Christine Hardman (Southwark) The Revd Canon Dr Alan Hargrave (Ely) The Rt Revd Martyn Jarrett (Northern Suffragans) The Revd Canon Simon Killwick (Manchester) The Revd Angus MacLeay (Rochester) Mrs Caroline Spencer (Canterbury) Consultants: Diocesan Secretaries: Mrs Jane Easton (Diocesan Secretary of Leicester) Diocesan Registrars: Mr Lionel Lennox (Diocesan Registrar of York) The Revd Canon John Rees (Diocesan Registrar of Oxford) 1 CONTENTS Page Number Glossary 3 Preface 5 Part 1: How the journey began 8 Part 2: How the journey unfolded 15 Part 3: How the journey was completed – the Committee‟s clause by clause consideration of the draft legislation A. The draft Bishops and Priests (Consecration and Ordination of Women) Measure 32 B. Draft Amending Canon No. 30 69 Part 4: Signposts for what lies ahead 77 Appendix 1: Proposals for amendment and submissions 83 Appendix 2: Summary of proposals and submissions received which raised points of substance and the Committee‟s consideration thereof Part 1. -

Review of 2015 from the Director and Chair of Council

REVIEW OF 2015 FROM THE DIRECTOR AND CHAIR OF COUNCIL We are pleased to present the RSCM’s Annual Review for 2015, to let you, the RSCM’s affi liates, members and donors, know what we achieved during the year. Three new posts took shape in 2015, and you will see below the work that we have been able to do in training worship leaders, developing singers, encouraging music-making in rural churches, and supporting worship with instruments. We are showing this through the stories of some of those who benefi ted from these programmes. The provision of a full-time post in training clergy and lay ministers Registered Offi ce 19 The Close is a particular ‘game-changer’. The gamut of RSCM’s work continues to be backed Salisbury up with relevant publications and sustained through the invaluable help of our Wiltshire SP1 2EB local Area volunteers. In these programme changes, and through a hymn book Registered Charity Number 312828 survey feeding into revisions to Sunday by Sunday, we are listening to the needs of Company Registration Number 250031 churches and members and, we hope, matching RSCM’s resources to those needs. Royal Patron Her Majesty the Queen 2015 has seen generous giving to the RSCM especially from its members and supporters, from grant-making trusts, and in several liberal bequests. We are Patrons The Right Revd The Moderator most grateful for your gifts which help to sustain and develop our work. We look of the General Assembly of forward to your feedback on the direction the RSCM is pursuing, and on how we the Church of Scotland His Grace the Archbishop of can best serve your needs. -

The Living Church

THE [IVING CHURCH AN INDEPENDENT WEEKLY SERVING EPISCOPALIANS• JULY 25, 2004 • $2.00 l . •,, \ /;.,...,'. ' :·~ , ··,-,. '.. ·,, / f Bishop Sisk Visits China The objective of THE LIVING CHURCH magazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK Opinion 10 Editor's Column A Contemporary Traditional Challenge 11 Editorials Heroes of the Faith 12 Reader's Viewpoint The Lambeth Commission: Possible Outcomes BY TONYCLAVIER 14 Letters 7 Spiritual Maturity Needed News 6 Lambeth Chastises Bishop Chane 7 Tensions Reported within Lambeth Commission OtherDepartments 4 Sunday's Readings 5 Books 16 People & Places 12 The Cover The Rt. Rev. Mark Sisk, Bishop of New York, greets a welcoming delegation during an official visit to China, May 11-20. Bishop Sisk, his wife Karen, Archdeacon Michael Kendall, Peter Ng of the Church of Our Savior, Manhattan, and Mary Beth Diss, editor of The Episcopal New Yorker, were guests of the China Christian Council (CCC) which was interested in studying the liturgy and structure of the Episcopal Church as well as building closer ecumenical ties. The CCC is the government-owned administrative agency for all protestant denominations holding legal worship services in the country. The Episcopal Neu· Yorker photo JULY 25. 2004 ·THE LIVING CH UR.CH 3 80-tid O~k SUNDAY'SREADINGS CHOIR CHAIR BecauseYou Ask Not Everyone who asks, receives (Luke 11:10) The Eighth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 12C), July 25, 2004 Gen, 18:20-33; Psalm '138; Col. -

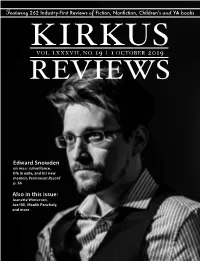

Edward Snowden Also in This Issue

Featuring 262 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVII, NO. 19 | 1 OCTOBER 2019 REVIEWS Edward Snowden on mass surveillance, life in exile, and his new memoir, Permanent Record p. 56 Also in this issue: Jeanette Winterson, Joe Hill, Maulik Pancholy, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Stories for Days HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, recently Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER told her Twitter followers that she has been reading a short story a day and [email protected] Vice President of Marketing that “it has been a deeply satisfying little project.” Lisa’s tweet reminded SARAH KALINA me of a truth I often lose sight of: You’re not required to read a story col- [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor lection cover to cover, all at once, as if it were a novel. As a result, I’ve ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] started hopscotching among stories by old favorites such as Lorrie Moore, Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Deborah Eisenberg, and Alice Munro. I’ve also turned my attention to [email protected] Children’s Editor some collections that are new this fall. Here are three: VICKY SMITH Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale edited by Lauren [email protected] Young Adult Editor Tom Beer Groff (Library of America, Oct. 1). Like so many neglected women writers of LAURA SIMEON [email protected] short fiction from the middle of the 20th century—Maeve Brennan, Edith Templeton, Mary Ladd Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE Gavell—Hale isn’t widely read today and is ripe for rediscovery. -

Annual Parochial Church Meeting Sunday 30Th April 2017

Annual Parochial Church Meeting Sunday 30th April 2017 Encountering God through transformative worship, challenging discipleship, generous hospitality & prayerful engagement. CONTENTS Dean’s Foreword 2 Cathedral Council 3 Fabric 4 Canon Chancellor 6 Education 8 Canon Precentor including Music 10 Vergers 11 TRANSFORMATIVE WORSHIP Society of Cathedral Ringers 12 Servers 13 Healing Group 13 PRAYERFUL ENGAGEMENT Junior Sing 14 Toddler Group 14 Gunwharf Chaplaincy 15 Sunyani Partnership Link 15 Hospital Wheelers 16 Food Bank Donations 16 Uniformed Groups 17 GENEROUS HOSPITALITY Churchwardens 19 Welcomers 20 Duty Chaplains 20 The Flower Guild 20 Holy Dusters 21 Friends of Portsmouth Cathedral 21 Cathedral Guides 22 Research Group 22 Cathedral Shop 23 Handbell Group 23 Craft and Chat Group 23 Memorial Garden 24 Cathedral Club 24 Parish Lunch Club 25 Social and Fundraising Events 25 CHALLENGING DISCIPLESHIP Quiet Afternoons 26 Messy Cathedral 26 Becket’s Bunch 26 1 THE DEAN’S FOREWORD Now well established, our annual theme for 2016 was particularly important. Religion is a major world issue affecting politics and community cohesion, and our theme of ‘Faiths:Connected’ enabled us to deepen relationships with our neighbours of other traditions and to learn something about each other. Using the medium of the arts allowed us to meet and interact in a relaxed way, and the artists receptions gathered people who had never been in the Cathedral before. Cathedrals are in the news! Following the critical visitation reports on Exeter and Peterborough last year, there has been much media comment. All Cathedrals face similar ambiguities ‐ they are the most successful part of the Church in terms of numbers, growth and community engagement, yet many are struggling financially. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 JANUARY 4/1 Church of England: Diocese of Chichester, Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 11/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Peter Wheatley, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Paul Williams, Bishop Jonathan Baker Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 18/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Chris Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. 25/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Tampere, Bishop Matti Repo Church of England: Diocese of Manchester, Bishop David Walker, Bishop Chris Edmondson, Bishop Mark Davies Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 FEBRUARY 1/2 Church of England: Diocese of Birmingham, Bishop David Urquhart, Bishop Andrew Watson Church of Ireland: Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, Bishop Paul Colton Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: Diocese of Elsinore, Bishop Lise-Lotte Rebel 8/2 Church in Wales: Diocese of Bangor, Bishop Andrew John Church of Ireland: Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough, Archbishop Michael Jackson 15/2 Church of England: Diocese of Worcester, Bishop John Inge, Bishop Graham Usher Church of Norway: Diocese of Hamar, Bishop Solveig Fiske 22/2 Church of Ireland: Diocese -

Communiqué 2013

The seventh meeting of the Anglican-Jewish Commission Wednesday 12 June 2013 The Anglican-Jewish Commission of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Chief Rabbinate of Israel has issued a declaration from the meeting held at the Haifa Municipality, Israel on 11 and 12 June 2013. The Commission's mandate provides for the Archbishop of Canterbury and the two Chief Rabbis (from the Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities) to meet each year alternately in England and Jerusalem. It also provides for an annual meeting of a Commission to study agreed themes together and to prepare meetings of the Archbishop and Chief Rabbis in which the Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem, The Rt Revd Suheil Dawani, also takes part. Communiqué of the Seventh Meeting of the Commission of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel and the Office of the Archbishop of Canterbury The seventh meeting of the Anglican-Jewish Commission of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel and office of the Archbishop of Canterbury was hosted by the former at the Haifa Municipality, Israel, on 11th and 12th June 2013 / 2nd and 3rd Tamuz 5773. The Commission's mandate is taken from the provisions of the joint declaration of the Archbishop and the Chief Rabbis made at Lambeth Palace on 6th September 2006 and confirmed at their subsequent meeting in Jerusalem. The meeting opened with a welcome and greeting by the Chief Rabbi Emeritus of Haifa and Chair of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel's Committee for Interreligious Dialogue, She’ar Yashuv Cohen, who has co-chaired the Anglican-Jewish Commission since its inception. The current chairs of the Commission are Archbishop Michael Jackson and Rabbi Dr Rasson Aroussi. -

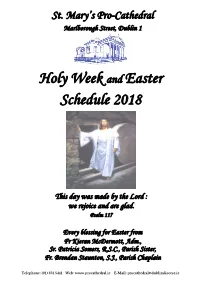

Holy Week and Easter Schedule 2018

St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral Marlborough Street, Dublin 1 Holy Week and Easter Schedule 2018 This day was made by the Lord : we rejoice and are glad. Psalm 117 Every blessing for Easter from Fr Kieran McDermott, Adm., Sr. Patricia Somers, R.S.C., Parish Sister, Fr. Brendan Staunton, S.J., Parish Chaplain Telephone: (01) 874 5441 Web: www.procathedral.ie E-Mail: [email protected] 25th March 6.00 p.m. Vigil Mass with Blessing of Palm - Cantor and Organ 9.30 a.m. Mass with Blessing of Palm St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral Girls’ Choir 11.00 a.m. Mass with Blessing of Palm and Procession Principal Celebrant - Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, D.D. Pueri Hebraeorum – Victoria, Mass XVII - Gregorian Chant, Improperium - Lassus, Christus Factus Est - Bruckner. The Palestrina Choir. Director—Blánaid Murphy. Organ Voluntary - Chorale Prelude ‘Valet will ich dir geben’ BWV 730 - J.S. Bach. Organist - Professor Gerard Gillen. Associate Organist -David Grealy. 6.00 p.m. Mass with Blessing of Palm - Pro Nuova Music Group Mass Times Monday 26th March 10.30 a.m. + 12.45 p.m. Tuesday 27th March Confessions Wednesday 28th March After 10.30 a.m. + 12.45 p.m. Masses Church closes at 2.00 p.m. on Tuesday 27th and Wednesday 28th March in order to facilitate the preparations for Holy Thursday. th - 29 March 10.30 a.m. The Chrism Mass Principal Celebrant - Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, D.D. Priests and representatives from every parish gather for Mass during which Holy Oils are blessed for the coming year and Renewal of Priestly Service.