Signature Redacted Signature Redacted___

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NMD, National Security Issues Featured at 2001 April Meeting In

April 2001 NEWS Volume 10, No. 4 A Publication of The American Physical Society http://www.aps.org/apsnews NMD, National Security Issues Featured Phase I CPU Report to be at 2001 April Meeting in Washington Discussed at Attendees of the 2001 APS April include a talk on how the news me- Meeting, which returns to Wash- dia cover science by David April Meeting ington, DC, this year, should arrive Kestenbaum, a self-described “es- The first phase of a new Na- just in time to catch the last of the caped physicist who is hiding out tional Research Council report of cherry blossom season in between at National Public Radio,” and a lec- the Committee on the Physics of scheduled sessions and special ture on entangled photons for the Universe (CPU) will be the events. The conference will run quantum information by the Uni- topic of discussion during a spe- April 28 through May 1, and will versity of Illinois’ Paul Kwiat. Other cial Sunday evening session at the feature the latest results in nuclear scheduled topics include imaging APS April Meeting in Washing- physics, astrophysics, chemical the cosmic background wave back- ton, DC. The session is intended physics, particles and fields, com- ground, searching for extra to begin the process of collect- putational physics, plasma physics, dimensions, CP violation in B me- ing input from the scientific the physics of beams, and physics sons, neutrino oscillations, and the community on some of the is- history, among other subdisci- amplification of atoms and light in The White House and (inset) some of its famous fictional sues outlined in the draft report, plines. -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

Proton Tomography Through Deeply Virtual Compton Scattering

Proton Tomography Through Deeply Virtual Compton Scattering Xiangdong Ji1, 2, ∗ 1Maryland Center for Fundamental Physics, Department of Physics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA 2INPAC, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 200240, P. R. China (Dated: November 7, 2018) Abstract In this prize talk, I recall some of the history surrounding the discovery of deeply virtual Compton scattering, and explain why it is an exciting experimental tool to obtain novel tomographic pictures of the nucleons at Jefferson Lab 12 GeV facility and the planned Electron-Ion Collider in the United States. arXiv:1605.01114v1 [hep-ph] 3 May 2016 ∗The 2016 Feshbach prize in theoretical nuclear physics talk given at APS April Meeting, Salt Lake City, Session U3: DNP Awards Session, Monday, April 18, 2016. The write-up is slightly expanded in details from the original talk. 1 It is certainly a great honor to have received the 2016 Herman Feshbach Prize in theoreti- cal nuclear physics by the American Physical Society (APS). I sincerely thank my colleagues in the Division of Nuclear Physics (DNP) to recognize the importance of some of the theoret- ical works I have done in the past, particularly their relevance to the experimental programs around the world. I. HERMAN FESHBACH AND ME Since this prize is in honor and memory of a great nuclear theorist, Herman Feshbach, it is fitting for me to start my talk by recalling some of my personal interactions with Herman. I first heard Feshbach back in 1982 when I was a freshman graduate student at Peking University before I knew anything about nuclear physics. -

William A. Fowler Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2d5nb7kj No online items Guide to the Papers of William A. Fowler, 1917-1994 Processed by Nurit Lifshitz, assisted by Charlotte Erwin, Laurence Dupray, Carlo Cossu and Jennifer Stine. Archives California Institute of Technology 1200 East California Blvd. Mail Code 015A-74 Pasadena, CA 91125 Phone: (626) 395-2704 Fax: (626) 793-8756 Email: [email protected] URL: http://archives.caltech.edu © 2003 California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Guide to the Papers of William A. Consult repository 1 Fowler, 1917-1994 Guide to the Papers of William A. Fowler, 1917-1994 Collection number: Consult repository Archives California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California Contact Information: Archives California Institute of Technology 1200 East California Blvd. Mail Code 015A-74 Pasadena, CA 91125 Phone: (626) 395-2704 Fax: (626) 793-8756 Email: [email protected] URL: http://archives.caltech.edu Processed by: Nurit Lifshitz, assisted by Charlotte Erwin, Laurence Dupray, Carlo Cossu and Jennifer Stine Date Completed: June 2000 Encoded by: Francisco J. Medina. Derived from XML/EAD encoded file by the Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics as part of a collaborative project (1999) supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. © 2003 California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: William A. Fowler papers, Date (inclusive): 1917-1994 Collection number: Consult repository Creator: Fowler, William A., 1911-1995 Extent: 94 linear feet Repository: California Institute of Technology. Archives. Pasadena, California 91125 Abstract: These papers document the career of William A. Fowler, who served on the physics faculty at California Institute of Technology from 1939 until 1982. -

Cornell Gets a New Chair

PEOPLE APPOINTMENTS & AWARDS Cornell gets a new chair Two prominent accelerator physicists and Cornell alumni, Helen T Edwards and her husband, Donald A Edwards, have endowed a chair in accelerator physics at Cornell.The chair is named after Boyce D McDaniel, pro fessor emeritus at Cornell. The first holder of the new chair is David L Rubin, professor of physics and director of accelerator physics at Cornell.The donors David Rubin is the first incumbent of the new Boyce McDaniel Chair of Physics at Cornell, asked that the new professorship should be endowed by Helen and Donald Edwards. The chair is named after Boyce D McDaniel. Left awarded to a Cornell faculty member whose to right: Boyce McDaniel, Donald Edwards, David Rubin, Helen Edwards and Maury Tigner, discipline is particle-beam physics and who director of Cornell's Laboratory of Nuclear Studies. would teach both graduate and undergradu ate students in addition to doing research. McDaniel, a previous director of nuclear ingthe commissioning of the Main Ring at Helen Edwards is a 1957 graduate of science at Cornell, was Helen Edwards' thesis Fermilab and providing advice for numerous Cornell, where she also earned her PhD in adviser. Initially a graduate student at Cornell, accelerator projects throughout the US, in 1966. She works at Fermilab and at DESY in he left during the Second World War to join the addition to his notable contributions to the Germany. She played a prominent role in the Manhattan Project and returned to complete accelerator and elementary particle physics construction of Fermilab'sTevatron and has his PhD, joining the faculty in 1946. -

Works of Love

reader.ad section 9/21/05 12:38 PM Page 2 AMAZING LIGHT: Visions for Discovery AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM IN HONOR OF THE 90TH BIRTHDAY YEAR OF CHARLES TOWNES October 6-8, 2005 — University of California, Berkeley Amazing Light Symposium and Gala Celebration c/o Metanexus Institute 3624 Market Street, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19104 215.789.2200, [email protected] www.foundationalquestions.net/townes Saturday, October 8, 2005 We explore. What path to explore is important, as well as what we notice along the path. And there are always unturned stones along even well-trod paths. Discovery awaits those who spot and take the trouble to turn the stones. -- Charles H. Townes Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. 3 Welcome Letter................................................................................................................. 5 Conference Supporters and Organizers ............................................................................ 7 Sponsors.......................................................................................................................... 13 Program Agenda ............................................................................................................. 29 Amazing Light Young Scholars Competition................................................................. 37 Amazing Light Laser Challenge Website Competition.................................................. 41 Foundational -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82197-1 - Out of the Shadows: Contributions of Twentieth-Century Women to Physics Edited by Nina Byers and Gary Williams Frontmatter More information Out of the Shadows: Contributions of Twentieth-Century Women to Physics Why are there not more prominent female physicists? Throughout history women have been denied access to higher learning and scientific laboratories. Today, traditional barriers faced by women in higher education have been breached. However, the female pioneers who overcame discrimination and became major players in their fields remain largely in the shadows. The importance of their work, achievements and contributions to science deserve recognition; the names of these pioneers deserve to be known. Out of the Shadows will help to bring a more gender-balanced perception of physicists. Here are detailed descriptions of important, original contributions made by women in the century from 1876 to 1976. Many female physicists and mathematicians, historically excluded from participation in science, emerged in this time. It was a period in which there was great progress in science and in the liberation of women from centuries of repression. This book documents both aspects of recent history. Many of the authors here are themselves distinguished scientists who have been actively engaged in the fields of physics about which they write. They write about modern developments in their fields with remarkable clarity and readability. The fields are as diverse as astrophysics, bio-molecular structure, chaos theory, geophysics, nuclear physics, particle physics, and surface physics. The writers include detailed accounts of important discoveries, place them in their historical context, give references to original papers, suggest books for further reading, and provide scientific biographies. -

Recipients of Major Scientific Awards a Descriptive And

RECIPIENTS OF MAJOR SCIENTIFIC AWARDS A DESCRIPTIVE AND PREDICTIVE ANALYSIS by ANDREW CALVIN BARBEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington December 16, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: James C. Hardy, Supervising Professor Casey Graham Brown John P. Connolly Copyright © by Andrew Barbee 2016 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. James Hardy for his willingness to serve on my committee when the university required me to restart the dissertation process. He helped me work through frustration, brainstorm ideas, and develop a meaningful study. Thank you to the other members of the dissertation committee, including Dr. Casey Brown and Dr. John Connolly. Also, I need to thank Andy Herzog with the university library. His willingness to locate needed resources, and provide insightful and informative research techniques was very helpful. I also want to thank Dr. Florence Haseltine with the RAISE project for communicating with me and sharing award data. And thank you, Dr. Hardy, for introducing me to Dr. Steven Bourgeois. Dr. Bourgeois has a gift as a teacher and is a humble and patient coach. I am thankful for his ability to stretch me without pulling a muscle. On a more personal note, I need to thank my father, Andy Barbee. He saw this day long before I did and encouraged me to pursue the doctorate. In addition, he was there during my darkest hour, this side of heaven, and I am eternally grateful for him. Thank you to our daughter Ana-Alicia. -

Mozart and Quantum Mechanics: an Appreciation of Victor Weisskopf

Physics Today Volume 56, No. 2, 43-47 (February 2003) Mozart and Quantum Mechanics: An Appreciation of Victor Weisskopf Weisskopf had a rare and harmonious blend of sentiment and intellectual rigor. He liked to say that his favorite occupations were Mozart and quantum mechanics. Kurt Gottfried and J. David Jackson Figure 1: Victor Weisskopf at about age 20 (photo courtesy of Duscha Scott Weisskopf) Victor Frederick Weisskopf, who died on 21 April 2002, was a leading figure in the second generation of theoretical physicists who expanded the reach of quantum mechanics following its discovery in 1925-26. That discovery proved to be the most profound and swift turning point in the history of physics since the time of Isaac Newton. Born in Vienna on 19 September 1908, Viki, as he was called by all who knew him, was too young to do original research in those first watershed years. But, like other outstanding members of his remarkable cohort, Viki was a fast study. He published his first landmark paper1 at the age of 22. Viki was eventually to become a major actor in a wide variety of settings, but all these roles were consequences of his achievements as a creative scientist. Therefore we devote here considerable attention to his contributions to fundamental theoretical physics. As a teenager, Viki became fascinated with astronomy and proudly listed a paper on the Perseid showers, based on a night's observation when he was not yet 15, as his first publication.2 The rich artistic and intellectual ambiance of pre-Nazi Vienna was to deeply influence his interests and attitudes throughout his life.3 Among his passions was music. -

IAS Letter Spring 2004

THE I NSTITUTE L E T T E R INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY · SPRING 2004 J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER CENTENNIAL (1904–1967) uch has been written about J. Robert Oppen- tions. His younger brother, Frank, would also become a Hans Bethe, who would Mheimer. The substance of his life, his intellect, his physicist. later work with Oppen- patrician manner, his leadership of the Los Alamos In 1921, Oppenheimer graduated from the Ethical heimer at Los Alamos: National Laboratory, his political affiliations and post- Culture School of New York at the top of his class. At “In addition to a superb war military/security entanglements, and his early death Harvard, Oppenheimer studied mathematics and sci- literary style, he brought from cancer, are all components of his compelling story. ence, philosophy and Eastern religion, French and Eng- to them a degree of lish literature. He graduated summa cum laude in 1925 sophistication in physics and afterwards went to Cambridge University’s previously unknown in Cavendish Laboratory as research assistant to J. J. the United States. Here Thomson. Bored with routine laboratory work, he went was a man who obviously to the University of Göttingen, in Germany. understood all the deep Göttingen was the place for quantum physics. Oppen- secrets of quantum heimer met and studied with some of the day’s most mechanics, and yet made prominent figures, Max Born and Niels Bohr among it clear that the most them. In 1927, Oppenheimer received his doctorate. In important questions were the same year, he worked with Born on the structure of unanswered. -

2013 Annual Report the American Physical Society Strives To

AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY TM 2013 ANNUAL REPORT THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY STRIVES TO Be the leading voice for physics and an authoritative source of physics information for the advancement of physics and the benefit of humanity Collaborate with national scientific societies for the advancement of science, science education, and the science community Cooperate with international physics societies to promote physics, to support physicists worldwide, and to foster international collaboration Have an active, engaged, and diverse membership, and support the activities of its units and members TM © 2014 American Physical Society Cover image: Sine waves. Illustration by Alan Stonebraker. FROM THE PRESIDENT his was a good year for physics, the APS, and its members. The Higgs continued to grab headlines, Twith the awarding of the Nobel Prize to François Englert and Peter Higgs. Their award-winning papers on the Higgs mechanism were published in Physical Review Letters (where else?). The DPF organized a “Higgs Fest” on Capitol Hill, attended by 10 members of Congress and several hundred others, to celebrate the Higgs and the U.S. role in discovering it. In this, the hundredth year of our publishing the Physical Review, the APS prepared to add a new jour- nal to the family—Physical Review Applied. Our newest journal will publish the highest-quality papers at the intersection of physics and engineering, in areas including materials, surface and interface science; device physics; condensed matter physics and optics. 2013 was a big year for APS global engagement. We had our first overseas Fellows receptions—in London and Tokyo—and the Executive Board held its annual retreat abroad, at the Kavli Royal Society International Centre at Chicheley Hall, just outside London. -

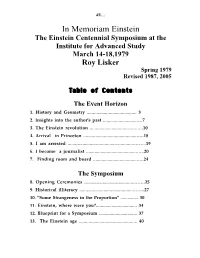

In Memoriam Einstein the Einstein Centennial Symposium at the Institute for Advanced Study March 14-18,1979 Roy Lisker Spring 1979 Revised 1987, 2005

#1... In Memoriam Einstein The Einstein Centennial Symposium at the Institute for Advanced Study March 14-18,1979 Roy Lisker Spring 1979 Revised 1987, 2005 Table of Contents The Event Horizon 1. History and Geometry ......................................... 3 2. Insights into the author's past ............................….7 3. The Einstein revolution ......................................…..10 4. Arrival in Princeton ............................................…..18 5. I am arrested ......................................................……..19 6. I become a journalist ..........................................…..20 7. Finding room and board ....................................…..24 The Symposium 8. Opening Ceremonies .........................................…….25 9. Historical illiteracy ............................................……..27 10. "Some Strangeness in the Proportion" ............... 30 11. Einstein, where were you?.................................. 34 12. Blueprint for a Symposium ................................ 37 13. The Einstein age ................................................ 40 #2... 14. Planck defenestrated : Wigner to the rescue .....…43 15. Einstein defenestrated : Dirac to the rescue .....…44 16. Dinner with Chandrasekhar ............................…….47 17. Lunch with the bureaucrats ..............................……48 18. Experimental relativity ....................................………49 19. The Cocktail Party ............................................……..52 20. Social responsibility at the IAS ..........................…..53