Chiswick House Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marble Hill Revived

MARBLE HILL REVIVED Business Plan February 2017 7 Straiton View Straiton Business Park Loanhead, Midlothian EH20 9QZ T. 0131 440 6750 F. 0131 440 6751 E. [email protected] www.jura-consultants.co.uk CONTENTS Section Page Executive Summary 1.0 About the Organisation 1. 2.0 Development of the Project 7. 3.0 Strategic Context 17. 4.0 Project Details 25. 5.0 Market Analysis 37. 6.0 Forecast Visitor Numbers 53. 7.0 Financial Appraisal 60. 8.0 Management and Staffing 84. 9.0 Risk Analysis 88. 10.0 Monitoring and Evaluation 94. 11.0 Organisational Impact 98. Appendix A Project Structure A.1 Appendix B Comparator Analysis A.3 Appendix C Competitor Analysis A.13 Marble Hill Revived Business Plan E.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E1.1 Introduction The Marble Hill Revised Project is an ambitious attempt to re-energise an under-funded local park which is well used by a significant proportion of very local residents, but which currently does very little to capitalise on its extremely rich heritage, and the untapped potential that this provides. The project is ambitious for a number of reasons – but in terms of this Business Plan, most importantly because it will provide a complete step change in the level of commercial activity onsite. Turnover will increase onsite fourfold to around £1m p.a. as a direct result of the project , and expenditure will increase by around a third. This Business Plan provides a detailed assessment of the forecast operational performance of Marble Hill House and Park under the project. -

Landscape,Associationism & Exoticism

702132/702835 European Architecture B landscape,associationism & exoticism COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice Pope's Villa at Twickenham Pevsner, Studies in Art, Architecture and Design, I, p 89 CCHISWICKHISWICK Chiswick, by Lord Burlington, begun 1725, south front Jeff Turnbull Chiswick and its garden from the west, by Pieter Rysbrack, 1748 Steven Parissien, Palladian Style (London 1994), p 99 Chiswick: drawing by Kent showing portico and garden John Harris, The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, his Villa and Garden at Chiswick (Montréal 1994), p 255 Chiswick: general view of house and garden, by P J Donowell, 1753 Jourdain, The Work of William Kent, fig 103 Doric column, Chiswick, perhaps by William Kent, c 1714 Harris, The Palladian Revival, p 71 Bagno, Chiswick, by Burlington, 1717 Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, III, p 26 Bagno and watercourse, Chiswick Jourdain, The Work of William Kent, fig 105 Chiswick: plan of the garden Architectural Review, XCV (1944), p 146. Chiswick, garden walks painting by Peter Rysbrack & engraving Lawrence Fleming & Alan Gore, The English Garden (London 1988 [1979]), pl 57. B S Allen, Tides in English Taste (1619-1800) (2 vols, New York 1958 [1937]), I, fig 33 Bagno and orange trees, Chiswick, by Rysbrack, c 1729-30 Fleming & Gore, The English Garden, pl 58 Bagno or Pantheon, Chiswick,probably by William Kent Jeff Turnbull Chiswick: design for the Cascade, by William Kent Harris, The Palladian Revival, p 14 Chiswick: the Great Walk and Exedra, by Kent. -

Landscape and Architecture COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

702132/702835 European Architecture B landscape and architecture COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice garden scene from a C15th manuscript of the Roman de la Rose Christopher Thacker, The History of Gardens (Berkeley [California] 1979), p 87 Monreale Cathedral, Palermo, Sicily, 1176-82: cloisters of the Benedictine Monastery commercial slide RENAISSANCERENAISSANCE && MANNERISMMANNERISM gardens of the Villa Borghese, Rome: C17th painting J D Hunt & Peter Willis, The Genius of the Place: the English Landscape Garden 1620-1820 (London 1975), p 61 Villa Medici di Castello, Florence, with gardens as improved by Bernardo Buontalenti [?1590s], from the Museo Topografico, Florence Monique Mosser & Georges Teyssot [eds], The History of Garden Design: The Western Tradition from the Renaissance to the Present Day (London 1991 [1990]), p 39 Chateau of Bury, built by Florimund Robertet, 1511-1524, with gardens possibly by Fra Giocondo W H Adams, The French Garden 1500-1800 (New York 1979), p 19 Chateau of Gaillon (Amboise), begun 1502, with gardens designed by Pacello de Mercogliano Adams, The French Garden, p 17 Casino di Pio IV, Vatican gardens, -

Best Wishes to All Friends for a Happy 2019!

BEST WISHES TO ALL FRIENDS FOR A HAPPY 2019! PARK WALK The next Friends event will be a walk on Sunday 3 March. Meet at the Café at 10am for a gentle explor- ation lasting about an hour and a half. Our December walk drew a friendly crowd, seen here slightly dazzled by the bright winter sun – do join us for to the next one! All welcome, just turn up. THE RETURN OF LOVEBOX AND CITADEL The CIC has agreed to the Lovebox and Citadel festivals returning to the same area of the park as 2018 on 12, 13 and 14 July. The Ealing Events announcement stated that several key aspects will be changed in the light of feed-back from residents, statutory authorities and other stakeholders. It refers to better management of pedestrian access to and from the park, improving parking arrangements and managing traffic. It promises other changes, details to come and a better consultation process with residents. Last year they brushed aside the fears of the local residents on the grounds they were highly experienced organisers, then afterwards made a series of abject apologies for the distress they created around the Park. If they are truly listening this year, the consultation meetings will be important. We will circulate the dates when we have them. 'KINGDOM OF THE ICE AGE' Animatronic woolly mammoths will be moving into the Park in the spring. The contractors will be setting up the exhibits from 27 March onwards and paying visitors will be admitted between 6 and 28 April. Everything will be off site by 7 May. -

Rare Books Special List for New York Antiquarian Book Fair April 11 – 14, 2013

Priscilla Juvelis – Rare Books Special List for New York Antiquarian Book Fair April 11 – 14, 2013 Architecture & Photography 1. Bickham, George. The beauties of Stow: or a description of pages a bit age toned at top edge but no the pleasant seat and noble gardens of the Right Honourable Lord spotting or foxing and the images clean Viscount Cobham. With above Thirty Designs, or drawings, and beautiful on vellum paper, a quite engraved on Copper-Plates, of each particular Building. London: collectable copy of a key book in early photography. E. Owen for George Bickham, M.DCC.L [1750]. $5,500 P. H. Emerson (1856-1936), born First edition complete with all 30 copperplate engravings of the gardens in Cuba to an American father and at Stow[e]. Page size: 3-7/8 x 6-½ inches; 67pp. + 3 pp. ads for other books British mother, earned a medical de- printed for George Bickham. Bound: brown calf with paneled spine, gree at Clare College, Cambridge. A lacking label on second panel, double gilt rule along all edges of front and keen ornithologist, he bought his first back panel, early ownership signatures on front pastedown, front cover camera to be used as a tool on bird- detached, pages a bit sunned and brittle but no foxing watching trips. He was involved in the at all, leaf F3 with ½ inch tear at fore edge, housed in formation of the Camera Club of Lon- marbled paper over boards slipcase with title printed don and soon after abandoned his ca- on brown leather label (probably originally on spine). -

English-Palladianism.Pdf

702132/702835 European Architecture B Palladianism COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice THETHE TRUMPETTRUMPET CALLCALL OFOF AUTHORITYAUTHORITY St George, Bloomsbury, London, by Hawksmoor, 1716- 27: portico Miles Lewis St Mary-le-Strand, London, by James Gibbs, 1714-17: in a view of the Strand Summerson, Architecture in Britain, pl 171A. In those admirable Pieces of Antiquity, we find none of the trifling, licentious, and insignificant Ornaments, so much affected by some of our Moderns .... nor have we one Precedent, either from the Greeks or the Romans, that they practised two Orders, one above another, in the same Temple in the Outside .... and whereas the Ancients were contented with one continued Pediment .... we now have no less than three in one Side, where the Ancients never admitted any. This practice must be imputed either to an entire Ignorance of Antiquity, or a Vanity to expose their absurd Novelties ... Colen Campbell, 'Design for a Church, of St Mary-le-Strand from the south-east my Invention' (1717) Miles Lewis thethe EnglishEnglish BaroqueBaroque vv thethe PalladianPalladian RevivalRevival Christopher Wren Colen Campbell -

Chiswick Gate, Factsheet

ONLY REMAINING2 HOMES A VERY LIMITED EDITION AT CHISWICK GATE Concord Court, located in one of West Chiswick itself retains a sense of village charm homes. These exceptional homes form the final London’s most sought-after residential areas, with all the convenience of city living. Residents phase of this stunning development from Berkeley. is inspired by the timeless quality of London’s will be situated close to the neo-palladium Concord Court benefits from well established garden squares. A beautifully landscaped, grandeur and extensive greenery of Chiswick facilities within the development. This includes a pedestrianised boulevard and lush garden House and Gardens, all just a short walk from square form the heart of the community, well equipped gym and a friendly concierge to the River Thames. offering tranquil green space difficult to find help with daily life. so close to the city and just moments from Concord Court at Chiswick Gate is an exclusive the charm of Chiswick High Road. collection of just nine spacious 1, 2 & 3 bedroom CITY OF THE CANARY RIVER CHISWICK HOUSE A B O U T T H E LONDON SHARD WHARF THAMES & GARDENS 7.8 MILES 8.5 MILES 11.3 MILES 0.2 MILES 0.4 MILES DEVELOPMENT Concord Court at Chiswick Gate is an exclusive collection of just nine spacious 1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments. These contemporary homes form the final phase of this exceptional development. Set within a beautifully landscaped, pedestrianised boulevard and garden square, creating a tranquil green space. Close to Chiswick High Road, for essential stores, plus an array of independent shops, TURNHAM GREEN bars and eateries UNDERGROUND 0.8 MILES A short walk to Chiswick House and Gardens The nearby River Thames is perfect for a stroll and water-based pursuits Designed by award-winning Architects, John Thompson & Partners Landscape Architects, McFarlane and Associates APARTMENT MIX CHISWICK STATION RICHMOND PARK Size Range (Sq. -

Willis Papers INTRODUCTION Working

Willis Papers INTRODUCTION Working papers of the architect and architectural historian, Dr. Peter Willis (b. 1933). Approx. 9 metres (52 boxes). Accession details Presented by Dr. Willis in several instalments, 1994-2013. Additional material sent by Dr Willis: 8/1/2009: WIL/A6/8 5/1/2010: WIL/F/CA6/16; WIL/F/CA9/10, WIL/H/EN/7 2011: WIL/G/CL1/19; WIL/G/MA5/26-31;WIL/G/SE/15-27; WIL/G/WI1/3- 13; WIL/G/NA/1-2; WIL/G/SP2/1-2; WIL/G/MA6/1-5; WIL/G/CO2/55-96. 2103: WIL/G/NA; WIL/G/SE15-27 Biographical note Peter Willis was born in Yorkshire in 1933 and educated at the University of Durham (BArch 1956, MA 1995, PhD 2009) and at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where his thesis on “Charles Bridgeman: Royal Gardener” (PhD 1962) was supervised by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner. He spent a year at the University of Edinburgh, and then a year in California on a Fulbright Scholarship teaching in the Department of Art at UCLA and studying the Stowe Papers at the Huntington Library. From 1961-64 he practised as an architect in the Edinburgh office of Sir Robert Matthew, working on the development plan for Queen’s College, Dundee, the competition for St Paul’s Choir School in London, and other projects. In 1964-65 he held a Junior Fellowship in Landscape Architecture from Harvard University at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, DC, returning to England to Newcastle University in 1965, where he was successively Lecturer in Architecture and Reader in the History of Architecture. -

Why You Should Live in London

FREE THE DEFINITIVE FAMILY GUIDE FOR WEST LONDON SUMMER 2015 ISSUE 5 SUMMER 2016 ISSUEFREE 9 ARE YOU IN OR OUT? WHY YOU SHOULD LIVE IN LONDON WHAT’S ON BOOKS EDUCATION STYLE ACTIVITIES re you in or out? I’m not talking Brexit, Remain or the EU referendum WELCOME but rather whether you are fully committed to a life in London. Sure, any A time spent on Rightmove will convince you into thinking you could have a better life in the countryside, living in a manor house, surrounded by acres of land and waited on by staff. But are we forgetting what it means to live in the city? Sophie Clowes thinks city life rocks and tells us why the capital is the best place to raise our kids. In a neat segue, we’re shining the spotlight on things to do in the big smoke with the kids in the holidays – from the best STEAM venues in London, to secret gardens in Surrey. And children’s entertainment experts Sharky & George share their ideas for alleviating boredom in the airport, on the beach and in the car. Beverley Turner reminds us why Dads rock, and Jo Pratt has some easy summer PHOTOGRAPHY & STYLING food to enjoy at home or abroad. The Little Revolution Productions [email protected] Happy Holidays! Victoria Evans SHOOT CO-ORDINATION Sarah Lancaster [email protected] citykidsmagazine.co.uk 07770 370 353 MODEL Olivia citykidswest @citykidswest To receive our newsletters, please sign up via our website at www.citykidsmagazine.co.uk INDEX 04 WE LOVE 07 WHAT’S ON 11 BEVERLEY TURNER 12 FEATURE CITY VS COUNTRY 15 FASHION 18 STYLE 19 SHARKY -

The Garter Room at Stowe House’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Michael Bevington, ‘The Garter Room at Stowe House’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XV, 2006, pp. 140–158 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2006 THE GARTER ROOM AT STOWE HOUSE MICHAEL BEVINGTON he Garter Room at Stowe House was described as the Ball Room and subsequently as the large Tby Michael Gibbon as ‘following, or rather Library, which led to a three-room apartment, which blazing, the Neo-classical trail’. This article will show Lady Newdigate noted as all ‘newly built’ in July that its shell was built by Lord Cobham, perhaps to . On the western side the answering gallery was the design of Capability Brown, before , and that known as the State Gallery and subsequently as the the plan itself was unique. It was completed for Earl State Dining Room. Next west was the State Temple, mainly in , to a design by John Hobcraft, Dressing Room, and the State Bedchamber was at perhaps advised by Giovanni-Battista Borra. Its the western end of the main enfilade. In Lady detailed decoration, however, was taken from newly Newdigate was told by ‘the person who shewd the documented Hellenistic buildings in the near east, house’ that this room was to be ‘a prodigious large especially the Temple of the Sun at Palmyra. Borra’s bedchamber … in which the bed is to be raised drawings of this building were published in the first upon steps’, intended ‘for any of the Royal Family, if of Robert Wood’s two famous books, The Ruins of ever they should do my Lord the honour of a visit.’ Palmyra otherwise Tedmor in the Desart , in . -

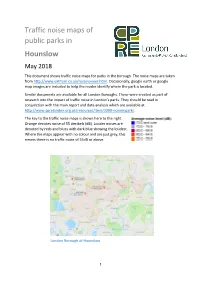

Traffic Noise Maps of Public Parks in Hounslow May 2018

Traffic noise maps of public parks in Hounslow May 2018 This document shows traffic noise maps for parks in the borough. The noise maps are taken from http://www.extrium.co.uk/noiseviewer.html. Occasionally, google earth or google map images are included to help the reader identify where the park is located. Similar documents are available for all London Boroughs. These were created as part of research into the impact of traffic noise in London’s parks. They should be read in conjunction with the main report and data analysis which are available at http://www.cprelondon.org.uk/resources/item/2390-noiseinparks. The key to the traffic noise maps is shown here to the right. Orange denotes noise of 55 decibels (dB). Louder noises are denoted by reds and blues with dark blue showing the loudest. Where the maps appear with no colour and are just grey, this means there is no traffic noise of 55dB or above. London Borough of Hounslow 1 1. Beaversfield Park 2. Bedfont Lake Country Park 3. Boston Manor Park 2 4. Chiswick Back Common 5. Crane Valley Park, South West Middlesex Crematorium Gardens, Leitrim Park 6. Dukes Meadows 3 7. Feltham Park, Blenheim Park, Feltham Arena, Glebelands Playing Fields 8. Gunnersbury Park 9. Hanworth Park 4 10. Heston Park 11. Hounslow Heath 12. Inwood Park 5 13. Jersey Gardens, Ridgeway Road North Park 14. Redlees Park 15. Silverhall Park 6 16. St John’s Gardens 17. Thornbury Park (Woodland Rd) 18. Thornbury Park (Great West Road) 7 19. Turnham Green 20. Lampton Park 21. -

Final Report BOSTON MANOR HOUSE and PARK

BOSTON MANOR HOUSE AND PARK: AN OPTIONS APPRAISAL Final Report June 2011 With financial support from English Heritage Peter McGowan Associates 7 Straiton View 57 - 59 Bread Street, Landscape Architects and Heritage Straiton Business Park Edinburgh EH3 9AH Management Consultants Loanhead, Midlothian EH20 9QZ tel: +44 (0)131 222 2900 6 Duncan Street T. 0131 440 6750 Edinburgh F. 0131 440 6751 fax: +44 (0)131 222 2901 EH9 1SZ E. [email protected] 0131 662 1313 www.jura-consultants.co.uk [email protected] CONTENTS Section Page Executive Summary i. 1. Introduction 1. 2. Conservation Management Plan – Boston Manor House 5. 3. Conservation Management Plan – Boston Manor Park 17. 4. Summary of Consultation 31. 5. Summary of Strategic Context 41. 6. User Market Appraisal 51. 7. Options 61. 8. Options Appraisal 101. 9. Conclusions and Recommendations 111. Appendix A List of Previous Studies Appendix B Market Appraisal Boston Manor House and Park EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E1.0 INTRODUCTION Jura Consultants was appointed by London Borough of Hounslow (LBH) to carry out an options appraisal for Boston Manor House and Park. The options appraisal has considered each element of the House and the Park to identify the most appropriate means of achieving the agreed vision set out in the Conservation Management Plans (CMP) for the House and Park developed in partnership with LDN Architects and Peter McGowan Associates respectively. E1.1 Background London Borough of Hounslow commissioned the options appraisal for Boston Manor House and Park to evaluate existing and potential uses for the House (and ancillary buildings) and the Park, and to determine the ability to sustain a long-term future for the House and Park.