An Engagement of Some Severity 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Cemeteries Name of Muhlple Property Ustlng Stale

it .-.'.'l-: . ~';"N PS WAS'-O~>~o,,",. ,.:::...::'"".,..,.",,),1..:" ,,,"-,', c;.·'''3i'''ci:;''';·2'-O'-C'=3'7'; 3':':"'''1:-'''8:'::';:':'6''''''''''';' ""~.'"-'-""=c' .'" ..;c, .... "'-. -'-:N~O:::cV'C-·"='2 71 "'.9""4~~15F"'~~'3 BNO>oi6>"P~'02'; 2 F' { f\J(l L. " No, l0U-0018 NPS Form 1().8OO.b :~. "'.~•• ~~' OMB (Reviled March 1992) United Stataa Dapal1menl of tha Interior National Pllrtc Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form NA'f'lONAI. REGISTSR Thlt form It uN<! for documentlll9 multlplo property groupo rolo~ng to on. or _eral hll10rle contexlS. ate InllluCllonl In How fa C<>mp/ere the MuIIip/e "'-'Y OocurrlMltaiJon I'omt (National Regll10r Bull8l1n 18S). C<>m~o each hem bY'"nte,ing tho r~uolled Inform.tlon, For .. ~ apace, use continuation _a (Form 1().9O().a), Use. typewriter, word proceoaor. or,wmputar to complota all hom •. -X. Nw 6ubmlttlon _ Amended SubmlSJIon A, . Name of Multiple Property Llatlng Civil War Era National Cemateries B, Auoclated Hlelorlo Contexte (Nome oach uaocl.ted hltlorlo context, Idonllfyjng thoma, geographlc.1 a,ea, and chronol~1 period for each.) Initial Development or Permanent Memorials to Civil War Sol diers Who Died in »efense of the Union - 1861 to 188l nameJtllle Therese T, Sammartino. Sraff Assistant date ___________ organlzatl(ln IJepartment of V~tcrnns Affl1irs street & number 810 Vermont AV(lnue. N, W. telephone (202) 523-3895 state _________ cltyortown W,~shitlglon. J).C. Zip code _~2~04"_'2'_"O'--___ D. CertIfication loA Iht dMlgnated SUlhodl)' Undet the Notional HlltoriO P.... /Vltlon Act of 1811e, at IrnoIMIId, I hfroby cortlfy that thll dOCumentatton form __ ~.. -

RICHMOND Battlefields UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Stewart L

RICHMOND Battlefields UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER THIRTY-THREE This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D.C. Price 25 cents. RICHMOND National Battlefield Park Virginia by Joseph P. Cullen NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES NO. 33 Washington, D.C., 1961 The National Park System, of which Richmond National Battlefield Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people. Contents Page Richmond 1 The Army of the Potomac 2 PART ONE THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, SUMMER 1862 On to Richmond 3 Up the Peninsula 4 Drewry's Bluff 5 Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) 6 Lee Takes Command 9 The Seven Days Begins 12 Beaver Dam Creek (Ellerson's Mill) 13 Gaines' Mill 16 Savage Station 18 Glendale (Frayser's Farm) 21 Malvern Hill 22 End of Campaign 24 The Years Between 27 PART TWO THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR RICHMOND, 1864-65 Lincoln's New Commander 28 Cold Harbor 29 Fort Harrison 37 Richmond Falls 40 The Park 46 Administration 46 Richmond, 1858. From a contemporary sketch. HE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR was unique in many respects. One Tof the great turning points in American history, it was a national tragedy op international significance. -

The Antietam and Fredericksburg

North :^ Carolina 8 STATE LIBRARY. ^ Case K3€X3Q£KX30GCX3O3e3GGG€30GeS North Carolina State Library Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/antietamfredericOOinpalf THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG- Norff, Carof/na Staie Library Raleigh CAMPAIGNS OF THE CIVIL WAR.—Y. THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG BY FEAISrCIS WmTHEOP PALFEEY, BREVET BRIGADIER GENERAL, U. 8. V., AND FORMERLY COLONEL TWTENTIETH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY ; MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETF, AND OF THE MILITARY HIS- TORICAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS. NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNEE'S SONS 743 AND 745 Broadway 1893 9.73.733 'P 1 53 ^ Copyright bt CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1881 PEEFAOE. In preparing this book, I have made free use of the material furnished by my own recollection, memoranda, and correspondence. I have also consulted many vol- umes by different hands. As I think that most readers are impatient, and with reason, of quotation-marks and foot-notes, I have been sparing of both. By far the lar- gest assistance I have had, has been derived from ad- vance sheets of the Government publication of the Reports of Military Operations During the Eebellion, placed at my disposal by Colonel Robert N. Scott, the officer in charge of the War Records Office of the War Department of the United States, F, W. P. CONTENTS. PAGE List of Maps, ..«.••• « xi CHAPTER I. The Commencement of the Campaign, .... 1 CHAPTER II. South Mountain, 27 CHAPTER III. The Antietam, 43 CHAPTER IV. Fredeeicksburg, 136 APPENDIX A. Commanders in the Army of the Potomac under Major-General George B. -

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park Virginia

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park Virginia by Joseph P. Cullen (cover of 1961 edition) National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 33 Washington, D.C. 1961 Contents a. Richmond b. The Army of the Potomac PART ONE THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, SUMMER 1862 c. On to Richmond d. Up the Peninsula e. Drewry's Bluff f. Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) g. Lee Takes Command h. The Seven Days Begins i. Beaver Dam Creek (Ellerson's Mill) j. Gaines' Mill k. Savage Station l. Glendale (Frayser's Farm) m. Malvern Hill n. End of Campaign o. The Years Between PART TWO THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR RICHMOND, 1864-65 p. Lincoln's New Commander q. Cold Harbor r. Fort Harrison s. Richmond Fall's t. The Park u. Administration For additional information, visit the Web site for Richmond National Battlefield Park Historical Handbook Number Thirty-Three 1961 This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D.C. Price 25 cents The National Park System, of which Richmond National Battlefield Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director Richmond, 1858. From a contemporary sketch. THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR was unique in many respects. -

Autographs and Americana Early American Currency Stocks and Bonds

AUTOGRAPHS AND AMERICANA EARLY AMERICAN CURRENCY STOCKS AND BONDS MAIL AND PHONE AUCTION CLOSING FRIDAY, JUNE 27, 2003 AT 8:00 P.M. E.S.T Scott J. Winslow Associates, Inc. Post Office Box 10240 Bedford, New Hampshire 03110 Toll Free in USA (800) 225-6233 Outside USA (603) 641-8292 Fax (603) 641-5583 TERMS OF SALE 1.) A 10% BUYERS PREMIUM WILL BE ADDED TO THE FINAL HAMMER PRICE. 2.) All items are guaranteed to be authentic. If an item is found not to be authentic, the full sale price will be refunded. 3.) All accounts are payable in full upon receipt of invoice unless other arrangements have been made prior to the sale. Any special credit terms should be made as early as possible. Title does not pass until full payment has been received. 4.) No “Buy” or unlimited bids will be accepted. 5.) We reserve the right to reject any bid we feel is not made in good faith. 6.) In the case of tie bids on the book, the earliest received shall take precedence. 7.) This is not an approval sale. Lots may not be returned except for reasons of authenticity or a material error in the catalog description. 8.) Please bid in U.S. dollars and only in whole dollar amounts. Fractions of a dollar will be rounded down to the nearest dollar. 9.) Some lots may be subject to a reserve. 10.) Shipping charges will be added to all invoices. 11.) The placing of a bid shall constitute the bidders acceptance of these terms of sale. -

BAB Manual EBOOK.Pdf

Contents 1. IntroduCtion to Brother against Brother 5 1.1. Overview 5 1.2. System Requirements 7 1.3. Installing the Game 8 1.4. Uninstalling the Game 8 1.5. Product Updates, Bonus Content and Registering your Game 8 1.6. Game Forums 10 1.7. Technical Support 10 1.8. Multi-player registration 10 2. Loading the Game 10 2.1. Main Menu 11 2.2. “Setup Local Game” Screen 12 3. What You see When the Scenario Begins 12 3.1. Map 13 3.2. Mini-map 14 3.3. Top of Screen 14 3.4. Game Buttons and Menus 15 3.5. Order Of Battle (OOB) Display or “Unit Roster” 20 3.6. Units 20 4. What You see after selectInG a unit 23 4.1. Control Box 23 4.2. Echelon Window 25 4.3. Map 26 5. Unit types, properties and StatuSes 27 5.1. Dynamic Statistics 28 5.2. Static Unit Characteristics 29 5.3. Unit Statuses 29 6. Commanding groups and units 32 6.1. Containers 32 6.2. Commanders 32 6.3. Headquarters Units 33 6.4. The Echelon Window and Commanding Brigades, Divisions, Corps and Armies 34 6.5. Automatic Functions of Corps, Divisions and Brigades 41 6.6. Selecting and Commanding Units 44 6.7. Commanding Independent Units 48 6.8. Automatic Functions of Unit Commanders 49 6.9. Temporary Brigade Attachments 49 6.10. The Effects of Going Out-of-Command 50 6.11. Misinterpreted Commands 51 7. tips on Finding the enemy 51 8. evaluating enemY StrenGth and Fighting CapaCity 52 9. -

The Antietam Manuscript of Ezra Ayres Carman

General Ezra Ayres Carman The Antietam Manuscript of Ezra Ayres Carman "Ezra Ayres Carman was Lt. Colonel of the 7th Regiment of New Jersey Volunteers during the Civil War. He volunteered at Newark, NJ on 3 Sept 1861, and was honorably discharged at Newark on 8 Jul 1862 (This discharge was to accommodate his taking command of another Regiment). Wounded in the line of duty at Williamsburg, Virginia on 5 May 1862 by a gunshot wound to his right arm in action. He also served as Colonel of the 13th Regiment of New Jersey Volunteers from 5 August 1862 to 5 June 1865. He was later promoted to the rank of Brigadier General." "Ezra Ayes Carman was Chief Clerk of the United States Department of Agriculture from 1877 to 1885. He served on the Antietam Battlefield Board from 1894 to 1898 and he is acknowledged as probably the leading authority on that battle . In 1905 he was appointed chairman of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park Commission." "The latest Civil War computer game from Firaxis is Sid Meier's "Antietam". More significant is the inclusion of the previously unpublished manuscript of Ezra Carman, the commanding officer of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers during the battle of Antietam. His 1800-page handwritten account of the battle has sat in the National Archives since it was penned and its release is of interest to people other than gamers." "As an added bonus, the game includes the previously unpublished Civil War manuscript of Ezra Carman, the commanding officer of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers. -

Military History Anniversaries 0916 Thru 093019

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 September Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Third Friday of Sep – National POW/MIA day to pay tribute to the lives and contributions of the more than 83,000 Americans who are still listed as Prisoners of War or Missing in Action. Sep 16 1776 – American Revolution: Battle of Harlem Heights » The Continental Army, under Commander-in-chief General George Washington, Major General Nathanael Greene, and Major General Israel Putnam, totaling around 9,000 men, held a series of high ground positions in upper Manhattan. Immediately opposite was the vanguard of the British Army totaling around 5,000 men under the command of Major General Henry Clinton. An early morning skirmish between a patrol of Knowlton's Rangers (an elite reconnaissance and espionage detachment of the Continental Army established by George Washington) and British light infantry pickets developed into a running fight as the British pursued the Americans back through woods towards Washington's position on Harlem Heights. The overconfident British light troops, having advanced too far from their lines without support, had exposed themselves to counter-attack. Washington, seeing this, ordered a flanking maneuver which failed to cut off the British force but in the face of this attack and pressure from troops arriving from the Harlem Heights position, the outnumbered British retreated. Meeting reinforcements coming from the south and with the added support of a pair of field pieces, the British light infantry turned and made a stand in open fields on Morningside Heights. -

Regimental History

650 Thirteenth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry. (THREE YEARS.) By S. MILLETT THOMPSON, late Second Lieutenant Thirteenth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, and Historian of tlie Regiment. THIS i-egiment volunteered under the call of Jul}' i, 1862, for 300,000 men. Gathered personally by their officers to be, two companies each were formed in Rockingham, Hillsborough, and Strafford counties; and one each in Grafton, Merrimack, Carroll, and Coos — all coming into Camp Colby, near Concord, between September 11 and 15. The muster-in of the rank and file was completed on September 20, and of the field and stafl", with the exception of Assistant-Surgeon John Sullivan, on September 23. militarj' outfit, including The colors were received on the afternoon of October 5 ; and at the same time a Springfield rifles, muzzle-loading, calibre 58. Space does not admit fairly of extended mention of individuals. This was at first almost wholly a regiment of native Americans and of New Hampshire's representative young men, many of them lineal descendants of the patriots of 1776 who fought in the Revolution. The average age was a little under twenty-five years, average height five feet and eight inches, and the most were of the dark blonde type. Its companies were fellow townsmen, and its members were in almost every trade and calling — many of whom, too, since the war closed, have gained prominent positions, commercial, professional, and in the Legislatures of States and Nation. The detachments, at the front, of its officers and men, upon special and staff duties, because of their intelligence and eflSciency, were very numerous — exceeding that of any regiment near and associated with it in the service. -

THE CHANCBI.LOR8VILLB Camraicn

CAVALRY OPIRATIONS AND '111111 SmCTS 01 THE CHANCBI.LOR8VILLB CAMrAICN A Che.i. pl'e••ced CO CIa. rAQ1I1ey of ella U... Am'! co-.d _ G.aral Staff Col1e.e ill ,.~ti.l fulfil1_t of tlae "equir_ca of tbe cle.r.e MAIDa or HlLITAIt aT AID SCIDCI by CHAlLIS I.. SMITH, JI... NAJOI., U. 8. MAlIKB CORPS B.8., Kortb Carolina State Oniv.rlity, 1961 Port L••veaworth, lAD'.' 1976 Document Title: Cavahy Operations and their Effects on the Chancellorsville Campaign, AD Number: ADA029993 Subject Categories: MILITARY OPERATIONS, STRATEGY AND TACTICS Corporate Author: ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLL FORT LEAVENWORTH KANS Title: Cavalry Operations and their Effects on the Chancellorsville Campaign, Descriptive Note: Final rept., Personal Authors: Smith,Charles ; Report Date: 11 JUN 1976 Pages: 139 PAGES Supplementary Note: Master's thesis. Descriptors: *VIRGINIA, *ARMY OPERATIONS, COMBAT EFFECTIVENESS, DEPLOYMENT, DECISION MAKING, LEADERSHIP, INFANTRY, THESES, HISTORY, MANEUVERS, MILITARY TACTICS, RECONNAISSANCE, MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS. Identifiers: Cavalry, Civil war(United States), Lessons learned, Chancellorsville campaign Abstract: The purpose of the study is to establish the effects of cavalry operations, both Federal and Confederate, on the Chancellorsville Campaign of the American Civil War. The primary source used for the study was the 'War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Confederate and Union Armies.' In analyzing the campaign, several factors emerge which help to explain Lee's victory and Hooker's defeat. One ofthese -

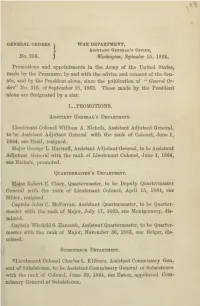

General Orders

GENERAL ORDERS WAR DEPARTMENT, Adjutant General’s Office, No. 256. Washington, September 15, 1864. Promotions and appointments in the Army of the United States, made by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Sen- ate, and by the President alone, since the publication of “ General Or- ders” No. 316, of September 18, 1863. Those made by the President alone are designated by a star. I..PROMOTIONS. Adjutant General’s Department. Lieutenant Colonel William A. Nichols, Assistant Adjutant General, to be Assistant Adjutant General with the rank of Colonel, June 1, 1864, vice Buell, resigned. Major GeorgeL. Hartsuff, Assistant Adjutant General, to be Assistant Adjutant General with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, June 1, 1864, vice Nichols, promoted. Quartermaster’s Department. Major Robert E. Clary, Quartermaster, to be Deputy Quartermaster General jvith the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, April 15, 1864, vice Sibley, resigned. Captain John C. McFerran, Assistant Quartermaster, to be Quarter- master with the rank of Major, July 17, 1863, vice Montgomery, dis- missed. Captain Winfield S. Hancock, Assistant Quartermaster, to be Quarter- master with the rank of Major, November 30, 1863, vice Belger, dis- missed. Subsistence Department. Colonel CharlesL. Kilburn, Assistant Commissary Gen. eral of Subsistence, to be Assistant Commissary General of Subsistence with the rank of Colonel, June 29, 1864, vice Eaton, appointed Com- missary General of Subsistence. 2 Major Henry F. Clarke, Commissary of Subsistence, to be Assistant Commissary General of Subsistence with the rank of Lieutenant Col - onel, June 29, 1864, vice Kilburn, promoted. JohnKellogg, Commissary of Subsistence, tobe Commissary of Subsistence with the rank of Major, June 29, 1864, vice Clarke, pro- moted. -

Maine GAR Posts & History

Grand Army of the Republic Posts - Historical Summary National GAR Records Program - Historical Summary of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Posts by State MAINE Prepared by the National Organization SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR INCORPORATED BY ACT OF CONGRESS No. Alt. Post Name Location County Dept. Post Namesake Meeting Place(s) Organized Last Mentioned Notes Source(s) No. PLEASE NOTE: The GAR Post History section is a work in progress (begun 2013). More data will be added at a future date. 000 (Department) N/A N/A ME Org. 10 January Ended 1947 Provisional Department organized December 1867; Permanent Beath, 1889; Carnahan, 1893; 1868 Department organized 10 January 1868 with 14 Posts. The National Encampment Department came to an end in 1947 with the death of its last Proceedings, 1948 members. 001 Post 1 Bath Sagadahoc ME (predates the practice of Org. 28 June Maine Farmer (Augusta), 14 assigning Post namesakes) 1867 Nov. 1867; Beath, 1889 001 Isaac C. Campbell Pembroke Washington ME 2LT Isaac C. Campbell (1841- Must'd 20 Oct. According to research by John ("JD") Rule, a lodge building built Dept. Proceedings, 1916 1864), Co. F, 6th Maine Inf., KIA 1873 by the Sons of Temperance and the Masons was owned -- in part -- at Spotsylvania Court House, VA, by the Isaac C. Campbell Post until 1919, when the Post sold its on 10 May 1864. Resident of share to Crescent Lodge, No. 78, AF&AM. A provision of the sale Pembroke, local hero. was that the Post artifact be allowed to remain in the building.