Building the New Kuwait Vision 2035 and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Role of Oil in the Growth Process of the Arab Gulf

Master’s Degree in Global Development and Entrepreneurship Final Thesis On the role of oil in the growth process of the Arab Gulf Supervisor Ch. Prof. Antonio Paradiso Graduand Sara Idda 853857 Academic Year 2018 / 2019 2 On the role of oil in the growth process of the Arab Gulf 3 A mia mamma e mio papà, che mi hanno insegnato ad essere forte nel rialzarmi dopo ogni caduta, ad avere il coraggio di vincere ogni sfida, dedico questo mio traguardo! Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Antonio Paradiso, the supervisor of my thesis, for his great availability and professionalism in these months of work and for always encouraging me; I also thank Prof. Silvia Vianello who has been a strong inspiration for me and a source of valuable advice. 4 Summary Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 9 1. Macroeconomic overview with some background about countries under-study: United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait. .................................................................................................. 11 1.1 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES: A brief focus on the principal points deal with ....................... 11 1.1.1 Some background of United Arab Emirates ............................................................... 12 1.1.2 The discovery of black gold ........................................................................................ 13 1.1.3 From the new oil boom to the Arab revolts of 2011 ................................................ -

Chatham House Corporate Members

CHATHAM HOUSE CORPORATE MEMBERS Partners AIG Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.a. Asfari Foundation JETRO London Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Leonardo S.p.a BP plc MAVA Foundation Carnegie Corporation of New York Ministry of Defence, UK Chevron Ltd Nippon Foundation Clifford Chance LLP Open Society Foundations Crescent Petroleum Robert Bosch Stiftung Department for International Development, UK Royal Dutch Shell European Commission Statoil ExxonMobil Corporation Stavros Niarchos Foundation Foreign & Commonwealth Office, UK Major Corporate Members AIA Group KPMG LLP Anadarko Kuwait Petroleum Corporation BAE Systems plc LetterOne Bank of America Merrill Lynch Liberty Global BV Barclays Linklaters Bayer Lockheed Martin UK BBC Makuria Investment Management BHP Mitsubishi Corporation Bloomberg Morgan Stanley BNP Paribas MS Amlin British Army Nomura International plc Brown Advisory Norinchukin Bank BT Group plc PricewaterhouseCoopers Caxton Asset Management Rabobank Casey Family Programs Rio Tinto plc Citi Royal Bank of Scotland City of London S&P Global CLP Holdings Limited Santander Control Risks Saudi Center for International and Strategic Partnerships Credit Suisse Saudi Petroleum Overseas Ltd Deloitte Schlumberger Limited Department for International Trade, UK Société Générale Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), The Standard Chartered Bank Diageo Stroz Friedberg Eni S.p.A. Sumitomo Corporation Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer Telstra Gardaworld The Economist GlaxoSmithKline Thomson Reuters Goldman Sachs International Toshiba Corporation -

Eirseptember 4, 2009 Vol

Executive Intelligence Review EIRSeptember 4, 2009 Vol. 36 No. 34 www.larouchepub.com $10.00 Blair’s Name Attached to Every Evil Obama Policy Obama Reappoints ‘Bailout Ben’: U.S. Will Pay the Price Will the President Jump on the LaRouche Lifeboat? Mars: The Next Fifty Years Keep Up with 21st CENTURY SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY Featured in the Spring 2009 issue 2009 (#10 out of 130 years) .46 2005 (#4) .62 • The Sun, Not Man, .9 .8 Still Rules Our Climate .7 .6 by Zbigniew Jaworowski .5 A leading scientist dissects the false “fi ngerprint” .4 of man-made warming and the Malthusian hand .3 promoting it. .2 2007 (#1) .74 –4 –2 –1 –.6 –.2 .2 .6 1 2 4 10 Ts Anomaly (˚C) • How Developing Countries Record High Can Produce Emergency Food And Gain Self-Suffi ciency 2009 2005 by Mohd Peter Davis and N. Yogendran 2007 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Month Malaysia’s revolutionary–4.8 –4 Deep–2 –1 Tropical–.6 –.2 .2 agricultural.6 1 2 4 6.6 system is a model for feeding the world—fast— and bringing the developing nations out of feudal poverty. • Stimulate the Economy: Build New Nuclear Plants! by Marsha Freeman Nuclear power is essential for the United States to recover from the ongoing breakdown crisis and become economically productive again. • SPECIAL REPORT: Water to Green Mexico’s Farmland On the PLHINO-PHLIGON, a great infrastructure project to move water from the mountains of the south to nourish the abundant farmland of Mexicos dry north, by Alberto Vizcarra Osuna. -

Blair Lands Another Deal

points – Tourist Organisation of Bel of Organisation –Tourist points distribution biggest paper’s the of out of distribution points distribution of out kicked Insight Belgrade Blair. Tony Fart EnglishGay titled abook of asaneditor listed was he cian that politi British the of critic anoutspoken such once was and war the during minister tion informa was who Vučić, Aleksandar ister, T Emma Lawrence Ivan Emirates. Arab United by befunded to believed deal under critic, his outspoken once Vučić, Aleksandar Serbian PM Blair willcounsel Serbia advising deal: another Blair lands grade centres. grade A BIRN. against campaign government-led the of acontinuation appears -inwhat centres Belgrade of Organisation Tourist at and airport Belgrade at stopped hasbeen Insight Belgrade of Distribution Blair will counsel the Serbian prime min Serbian prime the Blair willcounsel ANGELOVSKI GRAHAM-HARRISON MARZOUK ing of Belgrade in1999. Belgrade of ing bomb the of proponent chief asthe hisrole despite advise, to ispaid he countries of list the Serbiato Blairhasadded ony Continued on on Continued be distributed at one one at be distributed longer no will Insight, Belgrade newspaper, English language BIRN’s February, of s page 3 Vietnamese Vietnamese +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Belgrade Belgrade - - - - - student student Page 5 ‘home’ makes makes Opposition politicians say Blair is a “bizarre” choice of adviser for Vučić. ofadviserfor choice Blairisa“bizarre” Opposition politicianssay tourist locations in more than60coun inmore locations tourist other and seaports, at cruiseon liners, inairports, shops 1,700 over operates ongoing. remain this company with negotiations Airport, Tesla Nikola at outlets Dufry at has alsohalted paper Dufry, a global travel retailer that that retailer travel aglobal Dufry, news free the of distribution While Issue No. -

Changing a System from Within: Applying the Theory

CHANGING A SYSTEM FROM WITHIN: APPLYING THE THEORY OF COMMUNICATIVE ACTION FOR FUNDAMENTAL POLICY CHANGES IN KUWAIT A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Nasser Almujaibel May 10, 2018 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Nancy Morris, Advisory Chair, MSP / Media and Communication Dr. Brian Creech, Journalism. Media & Communication Dr. Wazhmah Osman, MSP/ Media & Communication Dr. Sean L. Yom, External Member, Political Science ABSTRACT Political legitimacy is a fundamental problem in the modern state. According to Habermas (1973), current legitimation methods are losing the sufficiency needed to support political systems and decisions. In response, Habermas (1987) developed the theory of communicative action as a new method for establishing political legitimacy. The current study applies the communicative action theory to Kuwait’s current political transformation. This study addresses the nature of the foundation of Kuwait, the regional situation, the internal political context, and the current economic challenges. The specific political transformation examined in this study is a national development project known as Vision of 2035 supported by the Amir as the head of the state. The project aims to develop a third of Kuwait’s land and five islands as special economic zones (SEZ). The project requires new legislation that would fundamentally change the political and economic identity of the country. The study applies the communicative action theory in order to achieve a mutual understanding between different groups in Kuwait regarding the project’s features and the legislation required to achieve them. ii DEDICATION ﻟﻠﺤﺎﻟﻤﯿﻦ ﻗﺒﻞ اﻟﻨﻮم ... اﻟﻌﺎﻣﻠﯿﻦ ﺑﻌﺪه iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my parents, my wife Aminah, and my children Lulwa, Bader, and Zaina: Your smiles made this journey easier every day. -

Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer?

Research Paper Mehran Kamrava, Gerd Nonneman, Anastasia Nosova and Marc Valeri Middle East and North Africa Programme | November 2016 Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Summary • The pre-eminent role of nationalized oil and gas resources in the six Gulf monarchies has resulted in a private sector that is highly dependent on the state. This has crucial implications for economic and political reform prospects. • All the ruling families – from a variety of starting points – have themselves moved much more extensively into business activities over the past two decades. • Meanwhile, the traditional business elites’ socio-political autonomy from the ruling families (and thus the state) has diminished throughout the Gulf region – albeit again from different starting points and to different degrees today. • The business elites’ priority interest in securing and preserving benefits from the rentier state has led them to reinforce their role of supporter of the incumbent regimes and ruling families. In essence, to the extent that business elites in the Gulf engage in policy debate, it tends to be to protect their own privileges. This has been particularly evident since the 2011 Arab uprisings. • The overwhelming dependence of these business elites on the state for revenues and contracts, and the state’s key role in the economy – through ruling family members’ personal involvement in business as well as the state’s dominant ownership of stocks in listed companies – means that the distinction between business and political elites in the Gulf monarchies has become increasingly blurred. -

Forklifts & Boom Lifts Lifts & Escalators Quarrying Railways Lighting

Reg No. 1 GC 027 • VOL 41 • No. 06 • June 2020 • BD3.5 | KD3 | RO3.5 | QR35 | SR35 | Dh35 www.gulfconstructiononline.com Forklifts & Boom Lifts Lifts & Escalators Quarrying Railways Lighting KUWAIT gulfconstructiononline.com Kuwait means halted progress completely, confirms a top official at a leading international mul- WAITING FOR VISION tidisciplinary firm based in Kuwait. “Like every other sector and industry, the construction sector now finds itself grap- TO MATERIALISE pling with a changed world, where projec- tions have been lowered, spending has been downsized and the project pipeline seems The health crisis created by the novel coronavirus and the record a little less robust,” Tarek Shuaib, CEO of low prices of oil have added to the manifold issues that Kuwait has Pace, tells Gulf Construction. faced over the years. However, given its significant sovereign wealth The Covid-19 pandemic has served a reserves, experts believe Kuwait will weather the storms well. double whammy to Kuwait, which is still hugely dependent on oil revenues, with oil prices having recently dropped to historic lows, and the resultant dive in business confidence. Since Kuwait instituted lock- downs to reduce the spread of the Covid-19 virus last March, around 39 per cent of businesses in the construction, contract- ing, architecture sector have shut down operations, revealed a busi- ness impact survey published by Bensirri PR (BPR), an independ- ent corporate, financial and polit- ical communications firm based in Kuwait. Nearly 31 per cent saw revenue drop by more than 80 per cent but were still operating when the sur- vey was conducted. -

China's Relations with the Arab and Gulf States

27 March 2020 China's relations with the Arab and Gulf States Author: COL Saud AlHasawi, KWT Army, CSAG CCJ5 The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of a number of international officers within the Combined Strategic Analysis Group (CSAG) and do not necessarily reflect the views of United States Central Command, nor of the nations represented within the CSAG or any other governmental agency. Key Points China has significantly increased its economic, political, and (marginally) security footprint in the Middle East in the past decade, becoming the biggest trade partner and external investor for many Arab and Gulf countries in the Central region. China still has a limited appetite for challenging the US-led security architecture in the Middle East or playing a significant role in regional politics. Yet the country’s growing economic presence is likely to pull it into wider engagement with the region in ways that could significantly affect US interests. The US should monitor China’s growing influence on regional stability and political dynamics, especially in relation to sensitive issues such as surveillance technology and arms sales. The US should seek opportunities for cooperative engagement with China in the Middle East, aiming to influence its economic role on constructive and security/stability initiatives. Background Information Although distant neighbors, China and the Arab countries have a rather ancient relationship that dates back to the first centuries of the Common Era, long before the advent of Islam. Nonetheless, until the end of the Twentieth Century, China and the Arab States only had a very limited trade relationship (spices, textiles etc). -

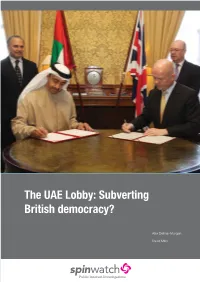

The UAE Lobby: Subverting British Democracy?

The UAE Lobby: Subverting British democracy? Alex Delmar-Morgan David Miller ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHORS Thanks to the Arab Organisation for Human Alex Delmar-Morgan Rights for its financial support for this report. is a freelance journalist in London and has written Thanks also to all those who have shared for a range of national titles information with us about or related to the UAE including The Guardian, lobby. We are indebted to a wide variety of people The Daily Telegraph, and who have shared stories and information with us, The Independent. He is the most of whom must remain nameless. We also former Qatar and Bahrain correspondent for thank Hilary Aked, Izzy Gill, Tom Griffin, Tom Mills. the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones. On a personal note, thanks to Narzanin Massoumi for her many contributions to this work. David Miller is a director of Public Interest Investigations, of which Spinwatch.org and CONFLICT OF INTEREST Powerbase.info are projects. He STATEMENT is also Professor of Sociology at the University of Bath in No external person had any role in the study, England. From 2013-2016 design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of he was RCUK Global Uncertainties Leadership data, or writing of the report. For the transparency Fellow leading a project on Understanding and policy of Public Interest Investigations and a list of explaining terrorism expertise in practice. grants received see: http://www.spinwatch.org/ index.php/about/funding Recent publications include: • The Quilliam Foundation: How ‘counter- PUBLIC INTEREST extremism’ works, (co-author, Public interest INVESTIGATIONS Investigations, 2018); • Islamophobia in Europe: counter-extremism Public Interest Investigations (PII) is an policies and the counterjihad movement, independent non-profit making organisation. -

Sovereign Wealth Funds in the Context of Subordinate Financialisation: the Turkey Wealth Fund in a Comparative Perspective

SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS IN THE CONTEXT OF SUBORDINATE FINANCIALISATION: THE TURKEY WEALTH FUND IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ALİ MERT İPEK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION SEPTEMBER 2019 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Ayata Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Galip YalmaN Supervisor Prof. Dr. Ebru Voyvoda (METU,ECON) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Galip YalmaN (METU, ADM) Prof. Dr. Hasibe Şebnem Oğuz (Başkent Üni., SBUİ) ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Ali Mert İpek Signature : iii ABSTRACT SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS IN THE CONTEXT OF SUBORDINATE FINANCIALISATION: THE TURKEY WEALTH FUND IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE İpek, Ali Mert M.S., Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Galip YalmaN September 2019, 182 pages As state-owned investment institutions, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are important actors in today’s global finance. -

730 Kuwait.Pdf

A GLOBAL / COUNTRY STUDY AND REPORT ON “Microanalysis of Different Industries of Kuwait” Submitted to Gujarat Technological University IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT OF THE AWARD FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Faculty Guide (Meetali Saxena) Submitted by Batch: 2011-13 L.J.Institute of Computer Applications MBA SEMESTER IV MBA PROGRAMME Gujarat Technological University Ahmedabad May, 2013 Students’ Declaration We, Students of L.J.Institute of Computer Application, Section : D , hereby declare that the report for Global/Country Study Report entitled “ Microanalysis Of Different Industries in kuwait is a result of our own work and our indebtedness to other work publications, references, if any, have been duly acknowledged. Place: Ahmedabad (Signature) Akash Tiwari Date : (Class Representative) Institute’s Certificate “Certified that this Global /Country Study and Report Titled “Microanalysis of Industries Of Kuwait” is the bonafide work of Students of L.J.Institute of Computer Application, who carried out the research under my supervision. I also certify further, that to the best of my knowledge the work reported herein does not form part of any other project report or dissertation on the basis of which a degree or award was conferred on an earlier occasion on this or any other candidate. Director Faculty Guide 2 (Dr. P. K. Mehta) (Meetali Saxena) Place: Ahmedabad Date : Executive summary 3 This report describes the findings and outlook of the business volume, products, and investment analysis of Kuwait. Kuwait is in Middle East, bordering the Arabian Gulf, between Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Climate of Kuwait Dry desert; short, cool winters; intensely hot summers. -

Un-Vaccinated 91.1% of COVID Dead

olympics Pages 15 & 16 THE FIRST ENGLISH LANGUAGE DAILY IN FREE KUWAIT markets Established in 1977 / www.arabtimesonline.com Page 9 FRIDAY-SATURDAY, AUGUST 6-7, 2021 / ZUL-HIJJAH 27-28, 1442 AH emergency number 112 NO. 17756 16 PAGES 150 FILS CDC PUTS KUWAIT IN HIGH-RISK CATEGORY FOR COVID Un-vaccinated 91.1% of COVID dead New cases 718 Opinion Kuwait likely to implement VAT KUWAIT CITY, Aug 5, (Agencies): Some KUWAIT CITY, Aug 5, (Agencies): Kuwait will most likely imple- According to the report, the oil exports and local gas consumption 91.1 per cent of the Any chance to get ment the Value Added Tax (VAT) this year or next year, says the will continue to be the driving forces behind the economic growth of latest World Bank report on the economies of the member-nations of Kuwait as the country still relies on oil as its main source of income. people who died from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). As part of measures taken in view of the corona pandemic, the GCC COVID-19 in July out of the dilemma? The World Bank also predicted that the economy of Kuwait will countries provided unemployment insurance; while fi ve of them includ- were not vaccinated, increase by 2.4 percent within 2021; followed by a projected 3.2 per- ed health insurance in their support measures, that is, except Kuwait. Kuwait Health Minis- cent growth in the next two years — 2022 and 2023. These measures somehow mitigated the dire consequences of shortened It presented projections for Kuwait on the following economic in- work hours and closures in a bid to curb the spread of corona.