Architecture, Design and Conservation Danish Portal for Artistic and Scientific Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESIGN DESIGN Traditionel Auktion 899

DESIGN DESIGN Traditionel Auktion 899 AUKTION 10. december 2020 EFTERSYN Torsdag 26. november kl. 11 - 17 Fredag 27. november kl. 11 - 17 Lørdag 28. november kl. 11 - 16 Søndag 29. november kl. 11 - 16 Mandag 30. november kl. 11 - 17 eller efter aftale Bredgade 33 · 1260 København K · Tlf. +45 8818 1111 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.dk 899_design_s001-276.indd 1 12.11.2020 17.51 Vigtig information om auktionen og eftersynet COVID-19 har ændret meget i Danmark, og det gælder også hos Bruun Rasmussen. Vi følger myndig- hedernes retningslinjer og afholder den Traditionelle Auktion og det forudgående eftersyn ud fra visse restriktioner og forholdsregler. Oplev udvalget og byd med hjemmefra Sikkerheden for vores kunder er altafgørende, og vi anbefaler derfor, at flest muligt går på opdagelse i auktionens udbud via bruun-rasmussen.dk og auktionskatalogerne. Du kan også bestille en konditions- rapport eller kontakte en af vores eksperter, der kan fortælle dig mere om specifikke genstande. Vi anbefaler ligeledes, at flest muligt deltager i auktionen uden at møde op i auktionssalen. Du har flere muligheder for at følge auktionen og byde med hjemmefra: • Live-bidding: Byd med på hjemmesiden via direkte videotransmission fra auktionssalen. Klik på det orange ikon med teksten ”LIVE” ud for den pågældende auktion. • Telefonbud: Bliv ringet op under auktionen af en af vores medarbejdere, der byder for dig, mens du er i røret. Servicen kan bestilles på hjemmesiden eller via email til [email protected] indtil tre timer før auktionen. • Kommissionsbud: Afgiv et digitalt kommissionsbud senest 24 timer inden auktionen ud for det pågældende emne på hjemmesiden. -

The Danish Sense of 'Design Better'

ENTREPRENEURSHIP PLATFORM COPENHAGEN BUSINESS SCHOOL enter #1 October 2013 Professor Robert Austin from the De partment of Management, Politics and Philosophy at CBS has studied the Danish company VIPP to explore why some services and products, like the VIPP trash bins, stand out in a crowd. Photo: VIPP PR photo The Danish sense of ‘design better’ Professor Robert Austin from the Department of Management, the Power of Plot to Create Extraordinary Products, which is ba- Politics and Philosophy at Copenhagen Business School heads sed on case studies of these companies. up the newly established Design and Entrepreneurship cluster He discovered, among other things, that VIPP ‘works harder on of the Entrepreneurship Platform. In his view, Denmark is one the intangibles that surround their physical products – the stories, of the best places in the world to understand how companies the imagery, the casual associations – than many other compa- become good at the deep and multifaceted sense of ‘design nies, and this helps them create meaning for their products. And better’ that makes products like VIPP’s trash bins stand out. He thus products that stand out as better and more desirable,’ he says. believes that there are new textbooks to be written about mana New cluster brings together design entrepreneurship ging creative businesses, and that some of this work involves competencies at CBS flipping ideas around to the opposite. ‘In the industrial society, Today, Robert Austin lives in Denmark and heads up the newly outliers were something companies tried to kill off. Today, har established Design and Entrepreneurship cluster of the Entrepre- vesting valuable outliers is at the core of innovation,’ he argues. -

81 Danish Modern, Then and Now Donlyn Lyndon

Peer Reviewed Title: Danish Modern, Then and Now -- The AIA Committee on Design, Historic Resources Committee [Forum] Journal Issue: Places, 20(3) Author: Lyndon, Donlyn FAIA Publication Date: 2008 Publication Info: Places Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/812847nf Acknowledgements: This article was originally produced in Places Journal. To subscribe, visit www.places-journal.org. For reprint information, contact [email protected]. Keywords: places, placemaking, architecture, environment, landscape, urban design, public realm, planning, design, volume 20, issue 3, forum, AIA, Donlyn, Lyndon, Danish, modern, then, now, historic, resources Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Forum Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA Danish Modern, Then and Now The American Institute of Architects Committee on Design Historic Resources Committee These Forum pages were printed under an agreement between Places/Design History Foundation and The American Institute of Architects. They report on the conference “Danish Modern: Then and Now,” held in Copenhagen, Denmark, in September, jointly sponsored by the Committee on Design (2008 Chair, Carol Rusche Bentel, FAIA) and the Historic Resources Committee (2008 Chair, Sharon Park, FAIA). T. Gunny Harboe, AIA, served as Conference Chair. For additional conference documentation and photos, go to: http://aiacod.ning.com/. In 2009, the COD theme will be “The Roots of Modernism and Beyond” (2009 Chair, Louis R. -

A Danish Museum Art Library: the Danish Museum of Decorative Art Library*

INSPEL 33(1999)4, pp. 229-235 A DANISH MUSEUM ART LIBRARY: THE DANISH MUSEUM OF DECORATIVE ART LIBRARY* By Anja Lollesgaard Denmark’s library system Most libraries in Denmark are public, or provide public access. The two main categories are the public, local municipal libraries, and the public governmental research libraries. Besides these, there is a group of special and private libraries. The public municipal libraries are financed by the municipal government. The research libraries are financed by their parent institution; in the case of the art libraries, that is, ultimately, the Ministry of Culture. Most libraries are part of the Danish library system, that is the official library network of municipal and governmental libraries, and they profit from and contribute to the library system as a whole. The Danish library system is founded on an extensive use of inter-library lending, deriving from the democratic principle that any citizen anywhere in the country can borrow any particular book through the local public library, free of charge, never mind where, or in which library the book is held. Some research libraries, the national main subject libraries, are obliged to cover a certain subject by acquiring the most important scholarly publications, for the benefit not only of its own users but also for the entire Danish library system. Danish art libraries Art libraries in Denmark mostly fall into one of two categories: art departments in public libraries, and research libraries attached to colleges, universities, and museums. Danish art museum libraries In general art museum libraries are research libraries. Primarily they serve the curatorial staff in their scholarly work of documenting artefacts and art historical * Paper presented at the Art Library Conference Moscow –St. -

The Danish Design Industry Annual Mapping 2005

The Danish Design Industry Annual Mapping 2005 Copenhagen Business School May 2005 Please refer to this report as: ʺA Mapping of the Danish Design Industryʺ published by IMAGINE.. Creative Industries Research at Copenhagen Business School. CBS, May 2005 A Mapping of the Danish Design Industry Copenhagen Business School · May 2005 Preface The present report is part of a series of mappings of Danish creative industries. It has been conducted by staff of the international research network, the Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics, (www.druid.dk), as part of the activities of IMAGINE.. Creative Industries Research at the Copenhagen Business School (www.cbs.dk/imagine). In order to assess the future potential as well as problems of the industries, a series of workshops was held in November 2004 with key representatives from the creative industries covered. We wish to thank all those who gave generously of their time when preparing this report. Special thanks go to Nicolai Sebastian Richter‐Friis, Architect, Lundgaard & Tranberg; Lise Vejse Klint, Chairman of the Board, Danish Designers; Steinar Amland, Director, Danish Designers; Jan Chul Hansen, Designer, Samsøe & Samsøe; and Tom Rossau, Director and Designer, Ichinen. Numerous issues were discussed including, among others, market opportunities, new technologies, and significant current barriers to growth. Special emphasis was placed on identifying bottlenecks related to finance and capital markets, education and skill endowments, labour market dynamics, organizational arrangements and inter‐firm interactions. The first version of the report was drafted by Tina Brandt Husman and Mark Lorenzen, the Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics (DRUID) and Department of Industrial Economics and Strategy, Copenhagen Business School, during the autumn of 2004 and finalized for publication by Julie Vig Albertsen, who has done sterling work as project leader for the entire mapping project. -

Scandi Navian Design Catalog

SCANDI NAVIAN DESIGN CATALOG modernism101 rare design books Years ago—back when I was graphic designing—I did some print advertising work for my friend Daniel Kagay and his business White Wind Woodworking. During our collaboration I was struck by Kagay’s insistent referral to himself as a Cabinet Maker. Hunched over my light table reviewing 35mm slides of his wonderful furniture designs I thought Cabinet Maker the height of quaint modesty and humility. But like I said, that was a long time ago. Looking over the material gathered under the Scandinavian Design um- brella for this catalog I now understand the error of my youthful judgment. The annual exhibitions by The Cabinet-Makers Guild Copenhagen— featured prominently in early issues of Mobilia—helped me understand that Cabinet-Makers don’t necessarily exclude themselves from the high- est echelons of Furniture Design. In fact their fealty to craftsmanship and self-promotion are constants in the history of Scandinavian Design. The four Scandinavian countries, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland all share an attitude towards their Design cultures that are rightly viewed as the absolute apex of crafted excellence and institutional advocacy. From the first issue of Nyt Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri published by The Danish Society of Arts and Crafts in 1928 to MESTERVÆRKER: 100 ÅRS DANSK MØBELSNEDKERI [Danish Art Of Cabinetmaking] from the Danske Kunstindustrimuseum in 2000, Danish Designers and Craftsmen have benefited from an extraordinary collaboration between individuals, manufacturers, institutions, and governments. The countries that host organizations such as The Association of Danish Furniture Manufacturers, The Association of Furniture Dealers in Denmark, The Association of Interior Architects, The Association of Swedish Furni- ture Manufacturers, The Federation of Danish Textile Industries, Svenska Slojdforeningen, The Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo put the rest of the globe on notice that Design is an important cultural force deserv- ing the height of respect. -

The Other Side of DANISH MODERN

ICONIC STYLE The other side of DANISH MODERN The Danish design movement was alive and very well in the decades before its acknowledged reign of supremacy. Jason Mowen highlights a few of its leading lights and their star pieces. Philip Arctander’s Clam chair (left) and Flemming Lassen’s The Tired Man armchair, in the petit salon of French interior designer Pierre Yovanovitch’s 17th-century chateau in Provence. IMAGE COURTESY PIERRE YOVANOVITCH PIERRE COURTESY IMAGE VOGUELIVING.COM.AU 69 ICONIC STYLE from left: Kaare Klint’s Faaborg chair (1915) and a rare daybed in Cuban mahogany (1917), one of only two produced. The daybed sold at Danish auction house Bruun Rasmussen in 2015 for 598,000 Danish krone (around $117,300); a pair of Klint’s early Easy armchairs in Cuban mahogany and Niger leather sold at Phillips in London in 2016 for £56,250 (around $92,580). OTHING IN THE VOCABULARY OF 20TH-CENTURY DESIGN is quite so reductive as ‘Danish Modern’, a phrase that conjures images of retro-looking armchairs, teak sideboards and ceramic table lamps, many of which are not even Danish. Whether it is the result of poor geographic knowledge N on our part or the enduring legacy of Denmark’s prolific design output during the 1950s and ’60s, a particularly golden era of Danish design from the interwar years is often overlooked. It was an era born of Modernism without mass-production and its KAARE KLINT virtue lies therein: furniture was designed and handcrafted slowly, No story on Danish Modern would be possible without the love child of a generation of Danish architects and the brilliant mention of Kaare Klint, whose 1915 Faaborg chair is cabinetmakers with whom they collaborated. -

Furniture Designer, Craftsman and Modernist Poul Kjærholm Occupies a Prominent Position in the Exclusive Company of Architects

POUL KJÆRHOLM (1929-1980) – A MASTER OF DETAIL Furniture designer, craftsman and modernist Poul Kjærholm occupies a prominent position in the exclusive company of architects and designers behind the classic and internationally acclaimed furniture from Fritz Hansen. During his 32-year career span, Kjærholm created a string of what have now become classic and exclusive icons in furniture, all born out of a perpetual, ambitious and challenging search for a minimalist ideal. Danish Poul Kjærholm was born in the small village of Øster Vrå in northern Jutland on January 8, 1929. At only 15 years of age he embarked on the journey that would eventually lead him to international fame when he was apprenticed to local master cabinetmaker Th. Grønbech in the neighbouring town of Hjørring. Having obtained his certificate of completed apprenticeship and a bronze medal for “a finely crafted mahogany- polished secretary”, as stated on the certificate, young Kjærholm decided to leave his childhood region and go to Copenhagen where he was admitted to study at The Danish School of Arts and Crafts in Frederiksberg the following year. At the school Poul Kjærholm studied under Hans J. Wegner while also following the lectures of Professor Kaare Klint at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. For a short period of time he studied under architect Jørn Utzon as well, but beyond that he was heavily influenced by international designers such as Americans Charles and Ray Eames, Bauhaus icon Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and the radical, Dutch minimalist Gerrit Rietveld. Poul Kjærholm proved his unique talent already in his early years at the Arts and Crafts school, when he engaged in bold and visionary experiments with novel materials and production technologies. -

Church Chair 48 About Church Chair 50 Pilot and Co-Pilot Chair 52 Dk3 6 Sideboard 54

No. 5 Contents About dk3 4 The Contemporary Collection 6 Jewel Table 8 LowLight Table 12 Tree Table 20 About Tree Table 22 dk3_3 Table 24 BlackWhite Table 26 Less Is More Table 28 Plank Sofa 34 About Plank Sofa 36 Plank Sofa 38 Tree and dk3_3 Coffee Table 40 BM2 Chair 42 Shaker Table 44 BM1 Chair 46 Church Chair 48 About Church Chair 50 Pilot and Co-Pilot Chair 52 dk3_6 Sideboard 54 ROYAL SYSTEM® 58 About RoyAL SysteM® and designer Poul Cadovius 60 RoyAL SysteM® 62 Designers 78 Detailed informations 80 dk3 wood 82 Thank you 84 Notes 86 2 ”The true aesthetic is natural, not man made” dk3 is a furniture design concept that emphasizes natural aesthetics. We create uniquely designed furniture that is shaped by nature and crafted by true enthusiasts. Always with a focus on personality, pride and sustainability. It is a vision of uniting the finest carpentry traditions with modern and classical furniture design through the fusion of timeless steel or brass components and high quality wood. The love of the organic material and uncompromising focus on quality is evident throughout the process, from the first design sketches to working in the carpentries in Denmark, where the furniture is finished and surface treated by hand. established in 2009, dk3 is exporting to more than 25 countries. dk3 is available in the finest lifestyle boutiques in New York City, London, Paris, Oslo, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Tokyo, Taipei, Seoul, Sydney, Mexico City and many more cities and it is with great pride, that we manufacture furniture pieces from such great Danish designers as Kaare Klint, Børge Mogensen, Poul Cadovius and more. -

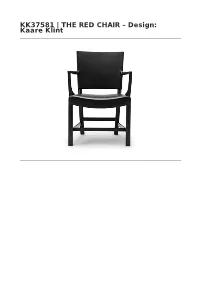

KK37581 | the RED CHAIR – Design: Kaare Klint BESCHREIBUNG

KK37581 | THE RED CHAIR – Design: Kaare Klint BESCHREIBUNG Klint war der festen Überzeugung, dass bestehende Archetypen moderne Designs beeinflussen können und sollten. Daher studierte er sorgfältig verschiedene englische Stuhldesigns - darunter das Chippendale-Design. Er kombinierte verschiedene Elemente und erschuf eine neue Konstruktion mit modernem Ausdruck und optimaler Tragkraft. Das erste Modell der Kollektion war der Red Chair Large (1927), das für den Hörsaal des Designmuseums Danmark entworfen wurde. 1930 stattete Klint den Red Chair Large für das Büro des dänischen Premierministers mit Armlehnen aus. Zudem entwarf er ein Sofa, um dem historischen Ambiente im Schloss Christiansborg gerecht zu werden. Für verschiedene Esstischgrößen konzipierte Klint zudem den Red Chair Small (1928) und den Red Chair Medium (1933). Der Stuhl ist aus Massivholz gefertigt. Sitzfläche und Rückenlehne sind mit Leder ausgestattet. DER DESIGNER Das Genie, das hinter Ikonen wie dem Faaborg Chair von 1914 und dem weltbekannten Safari Chair von 1933 steht, untermauerte 1929 seinen Status mit dem Gesamtentwurf des dänischen Pavillons für die Weltausstellung in Barcelona. Design und Architektur spielten schon früh eine große Rolle in Klints Leben. Als Sohn des Architekten Peder Vilhelm Jensen-Klint, zu dessen Werken die Grundtvigskirche in Kopenhagen zählt, entwickelte Kaare Klint schon früh ein Interesse daran, Funktion und Ästhetik miteinander in Einklang zu bringen. 1924 war er an der Gründung des Fachbereichs für Möbel- und Raumgestaltung an der Königlich-Dänischen Akademie der Künste beteiligt, an der er im folgenden Jahr als außerordentlicher Professor und dann schließlich als Professor arbeitete. Als Dozent und Designer war Klint eine Inspirationsquelle und legte den Grundstein für eine Generation der renommiertesten dänischen Möbeldesigner - darunter Hans J. -

Danish Vernacular – Nationalism and History Shaping Education

Danish Vernacular – Nationalism and History Shaping Education Inger Berling Hyams Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark ABSTRACT: Despite the number of internationally successful Danish architects like Jacobsen, Utzon and in recent years Ingels just to name a few, Danish architecture has always leaned greatly on international architectural history and theory. This is only natural for a small nation. However, since the beginning of Danish architecture as a professional discipline, there has also been a formation of a certain Danish vernacular. This paper explores how the teaching of and interest in Danish historical buildings could have marked the education of Danish architecture students. Through analysis of the drawings of influential teachers in the Danish school, particularly Nyrop, this development is tracked. This descriptive and analytic work concludes in a perspective on the backdrop of Martin Heidegger’s differentiation between Historie and Geschichte – how history was used in the curriculum and what sort of impact the teachers had on their students. Such a perspective does not just inform us of past practices but could inspire to new ones. KEYWORDS: Danish architecture education, National Romanticism, Martin Nyrop, Kay Fisker Figur 1: Watercolor by Arne Jacobsen, depicting the SAS hotel, Tivoli Gardens and City Hall in Copenhagen. Is there a link between functionalism and Danish vernacular? INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS VERNACULAR? Despite a long and proud tradition of Danish design, there has been very little research into Danish architecture and design education and it was discovering this lack that sparked my research. Through an investigation of different educational practices in the 20th century I am concerned with answering how knowledge is produced and transferred through the act of drawing. -

OW149 | COLONIAL CHAIR – Design: Ole Wanscher

OW149 | COLONIAL CHAIR – Design: Ole Wanscher DESCRIPTION The Colonial Chair is a beautiful easy chair with a simple and refined expression. Despite the chair´s slim and elegant dimensions, the chair is very stable. It is ideal in rooms where flexibility and lightness is desired. It has an elegant and timeless expression with its visible solid wood frame and softly rounded cushions providing great comfort. The seat is made of hand woven cane and can be removed from the frame of the chair and replaced if so needed. The cushions consist of cold foam and can be upholstered in fabric or leather upon request. The cushions are turn-able in fabric - but not in leather. HISTORY Designed by Ole Wanscher in 1949. Ole Wanscher designed the Colonial Chair in 1949 but it wasn´t until the mid-1950´s that the chair was put in to production by the Danish cabinetmaker, PJ Furniture. The name of the chair, "Colonial", relates to Wanschers fascination with 1700-century English furniture design. The Colonial Chair is by far Ole Wanschers most known piece of furniture. THE DESIGNER Ole Wanscher (1903-1985), was born in Copenhagen in 1903 and was an architect and professor of architecture with furniture designs as his specialty. He came to shape Danish furniture, both as an active designer and as a master teacher. His furniture designs are now considered to be modern classics - sophisticated and functional with an exquisite attention to detail. Construction and form was of the utmost importance to Ole Wanscher, treating furniture design as if it was a branch of architecture.