Zimbabwe: Getting the Transition Back on Track

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival Events 1

H.E. Lieutenant-General Olusegun Obasanjo, Head of State of Nigeria and Festival Patron. (vi) to facilitate a periodic 'return to origin' in Africa by Black artists, writers and performers uprooted to other continents. VENUE OFEVENTS The main venue is Lagos, capital of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. But one major attraction, the Durbar. will take place in Kaduna, in the northern part basic facts of the country. REGISTRATION FEES Preparations are being intensified for the Second World There is a registration fee of U.S. $10,000 per partici- Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture to be held pating country or community. in Nigeria from 15th January to 12th February, 1977. The First Festival was held in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966. GOVERNING BODY It was then known simply as the World Festival of Negro The governing body for the Festival is the International Arts. Festival Committee representing the present 16 Festival At the end of that First Festival in 1966, Nigeria was Zones into which the Black African world has been invited to host the Second Festival in 1970. Nigeria divided. These 16 Zones are: South America, the accepted the invitation, but because of the internal Caribbean countries, USA/Canada, United Kingdom and situation in the country, it was not possible to hold the Ireland, Europe, Australia/Asia, Eastern Africa, Southern Festival that year. Africa, East Africa (Community), Central Africa I and II, At the end of the Nigerian civil war, the matter was WestAfrica (Anglophone), West Africa (Francophone) I resuscitated, and the Festival was rescheduled to be held and II, North Africa and the Liberation Movements at the end of 1975. -

The Sinister Political Life of Community

NIGER DELTA ECONOMIES OF VIOLENCE WORKING PAPERS Working Paper No. 3 THE SINISTER POLITICAL LIFE OF COMMUNITY Economies of Violence and Governable Spaces in the Niger Delta, Nigeria Michael Watts Director, Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, USA 2004 Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, USA The United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC, USA Our Niger Delta, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 1 The Sinister Political Life of Community: Economies of Violence and Governable Spaces in the Niger Delta, Nigeria Michael Watts We seek to recover the . life of the community, as neither the “before” nor the “after” picture of any great human transformation. We see “communities” as creatures with an extraordinary and actually . quite sinister political life in the ground of real history. Kelly and Kaplan (2001:199) “Community” is an archetypal keyword in the sense deployed by Raymond Williams (1976). A “binding” word, suturing certain activities and their interpretation, community is also “indicative” (Williams’s term once again) in certain forms of thought. Deployed in the language for at least five hundred years, community has carried a range of senses denoting actual groups (for example “commoners” or “workers”) and connoting specific qualities of social relationship (as in communitas). By the nineteenth century, community was, of course, invoked as a way of talking about much larger issues, about modernity itself. Community—and its sister concepts of tradition and custom—now stood in sharp contrast to the more abstract, instrumental, individuated, and formal properties of state or society in the modern sense. A related shift in usage subsequently occurred in the twentieth century, when community came to refer to a form or style of politics distinct from the formal repertoires of national or local politics. -

Chronological Table

Chronological Table Date Contemporary events Publications 1834 Abolition of slavery in Tennyson, '0 Mother the British empire Britain Lift Thou Up' 1837 Accession of Queen McCulloch, Statistical Victoria; Canadian Account of the British Rebellions Empire 1838 Apprenticeship system in Thackeray, the West Indies abolished Tremendous Adventures of Major Gahagan 1839 Lord Durham's Report; Carlyle, Chartism; Aden annexed; First Taylor, Confessions of Afghan War (1839-42) a Thug 1840 New Zealand annexed; Buxton, The African Union of the two Canadas Slave Trade; Taylor, Tippoo Sultaun 1841 Livingstone in Africa; Carlyle, Heroes & Buxton's Niger Hero Worship; expedition; Retreat from Marryat, Masterman Kabul Ready; Merivale, Lectures on Colonization and Colonies 1842 Hong Kong annexed Tennyson, Poems 1843 Natal annexed; Carlyle, Past & Present 183 184 The Imperial Experience Maori Wars (1843--47); Sind conquered 1845 First Sikh War Martineau, Dawn Island 1846 Kaffraria and Labuan annexed 1847 Governor of Cape Dickens, Dombey & Colony becomes High Son; Disraeli, Tancred; Commissioner for South Longfellow, Africa 'Evangeline'; Thackeray, Vanity Fair 1848 Transvaal and Orange Ballantyne, Hudson Free State annexed; Bay; Mill, Principles of Second Sikh War; Sa tara, Political Economy; Jaipur & Sambalpur 'lapse' Thackeray, History of to the British crown Pendennis 1849 Navigation Acts abolished Carlyle, 'The Nigger Question'; Dickens, David Copperfield; Lytton, The Caxtons; Wakefield, View of the Art of Colonization 1850 Australian Colonies Carlyle, Latter-Day Government Act; Baghat Pamphlets; Knox, Races lapses of Men 1851 Great Exhibition; Australian gold rush; Victoria becomes a separate colony 1852 Sand River Convention; Burton, Miss ion to Lower Burma annexed; Gelele; Dickens, Bleak Udaipur lapses House; Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin Chronological Table 185 1853 Jhansi lapses Dickens, 'The Noble Savage'; Thackeray, The N ewcomes 1854 Bloemfontein Convention; N agpur lapses; Crimean War (1854-6) 1855 New constitutions for C. -

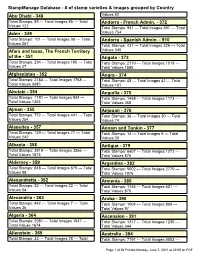

Stampmanage Database

StampManage Database - # of stamp varieties & images grouped by Country Abu Dhabi - 348 Values 82 Total Stamps: 89 --- Total Images 85 --- Total Andorra - French Admin. - 372 Values 122 Total Stamps: 941 --- Total Images 587 --- Total Aden - 349 Values 754 Total Stamps: 101 --- Total Images 98 --- Total Andorra - Spanish Admin. - 910 Values 267 Total Stamps: 437 --- Total Images 326 --- Total Afars and Issas, The French Territory Values 340 of the - 351 Angola - 373 Total Stamps: 294 --- Total Images 180 --- Total Total Stamps: 2170 --- Total Images 1019 --- Values 27 Total Values 1580 Afghanistan - 352 Angra - 374 Total Stamps: 2184 --- Total Images 1768 --- Total Stamps: 48 --- Total Images 42 --- Total Total Values 3485 Values 101 Aitutaki - 354 Anguilla - 375 Total Stamps: 1191 --- Total Images 934 --- Total Stamps: 1468 --- Total Images 1173 --- Total Values 1303 Total Values 365 Ajman - 355 Anjouan - 376 Total Stamps: 772 --- Total Images 441 --- Total Total Stamps: 36 --- Total Images 30 --- Total Values 254 Values 74 Alaouites - 357 Annam and Tonkin - 377 Total Stamps: 139 --- Total Images 77 --- Total Total Stamps: 14 --- Total Images 6 --- Total Values 242 Values 28 Albania - 358 Antigua - 379 Total Stamps: 3919 --- Total Images 3266 --- Total Stamps: 6607 --- Total Images 1273 --- Total Values 1873 Total Values 876 Alderney - 359 Argentina - 382 Total Stamps: 848 --- Total Images 675 --- Total Total Stamps: 5002 --- Total Images 2770 --- Values 88 Total Values 7076 Alexandretta - 362 Armenia - 385 Total Stamps: 32 --- Total -

Unity in Diversity: a Comparative Study of Selected Idioms in Nembe (Nigeria) and English

Intercultural Communication Studies XXIII: 2 (2014) TEILANYO Unity in Diversity: A Comparative Study of Selected Idioms in Nembe (Nigeria) and English Diri I. TEILANYO University of Benin, Nigeria Abstract: Different linguistic communities have unique ways of expressing certain ideas. These unique expressions include idioms (as compared with proverbs), often being fixed in lexis and structure. Based on assumptions and criticisms of the Sapir-Whorfian Hypothesis with its derivatives of cultural determinism and cultural relativity, this paper studies certain English idioms that have parallels in Nembe (an Ijoid language in Nigeria’s Niger Delta). It is discovered that while the codes (vehicles) of expression are different, the same propositions and thought patterns run through the speakers of these different languages. However, each linguistic community adopts the concepts and nuances in its environment. It is concluded that the concept of linguistic universals and cultural relativity complement each other and provide a forum for efficient communication across linguistic, cultural and racial boundaries. Keywords: Idioms, proverbs, Nembe, English, proposition, equivalence, Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, linguistic universals, cultural relativity 1. Introduction: Language and Culture (Unity or Diversity) The fact that differences in culture are reflected in the patterns of the languages of the relevant cultures has been recognized over time. In this regard, one of the weaknesses modern linguists find in classical (traditional) grammar is the “logical fallacy” (Levin, 1964, p. 47) which assumed “the immutability of language” (Ubahakwe & Obi, 1979, p. 3) on the basis of which attempts were made to telescope the patterns of modern European languages (most of which are at least in past “analytic”) into the structure of the classical languages like Greek and Latin which were largely “synthetic”. -

20019 DBQ 1A: Score of a 8 for Years After the Berlin Conference

20019 DBQ 1A: Score of a 8 For years after the Berlin Conference, various European powers raced to occupy and colonize land in Africa. It was a time of growth for Europe, but what was it for Africa? Africa’s fate was being decided for it by the European invaders. Not all Africans just stood by and watched, however. There was a wide range of actions and reactions to the scramble for Africa from the Africans themselves, from giving in peacefully to fighting back with all of their might. Many Africans were afraid of European power, so they just gave in to the scramble without a fight. In 1886, the British government commissioned the Royal Niger Company to administer and develop the Niger River delta. Many African rulers just signed their land away (doc 1). This document is official and provides no personal report, so it is possible that the rulers did not give in entirely peacefully, all we know is that they gave in. A personal record of the Niger River delta dealings would help immensely to tell how easily the rulers signed. Ashanti leader Pyempeh I turned down a British offer of protectorate status, but he said that the Ashanti would always remain friendly with “all White men” (doc 2). Ndansi Kumalo, an African veteran of the Ndansi Rebellion tells how at first his people surrendered to the British and tried to continue living their lives as they always had (doc 4). Samuel Manherero, a Herero leader, wrote to another African leader about how the Herero people were trying to be obedient and patient with the Germans (doc 7). -

Author: Title: Year

This work is made freely available under open access. AUTHOR: TITLE: YEAR: OpenAIR citation: This work was submitted to- and approved by Robert Gordon University in partial fulfilment of the following degree: _______________________________________________________________________________________________ OpenAIR takedown statement: Section 6 of the “Repository policy for OpenAIR @ RGU” (available from http://www.rgu.ac.uk/staff-and-current- students/library/library-policies/repository-policies) provides guidance on the criteria under which RGU will consider withdrawing material from OpenAIR. If you believe that this item is subject to any of these criteria, or for any other reason should not be held on OpenAIR, then please contact [email protected] with the details of the item and the nature of your complaint. This thesis is distributed under a CC ____________ license. ____________________________________________________ A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF CORPORATE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT (CCE) IN THE NIGER DELTA Olushola Emmanuel Ajide HND (Ilorin), PGD (Awka), MSc. (Coventry), PGCert (RGU) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Robert Gordon University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 Author: Olushola Emmanuel Ajide Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD. Title: A Critical Assessment of Corporate Community Engagement (CCE) In The Niger Delta: A Stakeholder Perspective of The Nigerian Oil And Gas Industry Abstract This thesis makes a new contribution to the field of corporate social responsibility in the area of corporate community engagement (CCE) and public relations in the area of organization-public relationships (OPRs). The thesis focuses on the Nigerian oil and gas industry community relationship in the Niger Delta region. This study provides valuable insights into how CCE works for enhancing stakeholder relationship and other desirable outcomes and thereby contributes to the growing body of knowledge on CSR in public relations. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

4 P H I L a T E L I C C H R O N I C L E ...A N D F L D O E R T I S E R

. O r • ♦ 4 " 4 * 4 - Philatelic Chronicle . .V X♦ * -AK*- ♦ . and fldoertiser. t 4 * VOLUME VIII. ( 1 8 9 8 — 18 9 9 . > /J s- A >’ & A 4 ^ 4 * 4 * X A * r A V M i 4 ^ t r R I M F n i,’»lt JHK Ji A lt ^ y A 4 * K A NDAL 1- il K U T 11 L IM, A s t o s P i u n t i m . W o r k s , A r t v s t r o s s . B iiim is i. h \m . 4 * X t a :.ii 1 i r-tistil.r m A 4- * r 'MIL I’ ll 1 L A 1 LL i ( i’ l' |; L I 5 11 I N G Co, * 4 t i F u M'HAM U u AU, H a MJSUu Ii i h , IJ IKMINL-HAM. 4-’> r 4 - 4 ^ A ' A j # 7^ tv. THE PHILATELIC CHRONICLE AND ADVERTISER. COMPARE OUR PRICES WITH OTHER DEALERS’1 M IDLAND 5TAM P CO., 11, Norttiam pton St*, B IR M IN G H A M , UNUSED STAMPS. CHEAP SETS. 1 1 2 i set. Doz. sets. 8. d. 3. d . s . d . a. d . British Beohuanaland, surcharged on Bavaria, 17 variouB . 0 5 4 0 English, |d., Id., 2d., 4d., 6d. and Borneo, 1897, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 .. 0 10 9 6 1/-, set of 6 3 6 Brazil, 22 various.. .. 0 10 7 0 Dominica, Id. .; 1 4 Belgium, 40 various . 0 6 5 6 „ *d. -

Sir Frederick Lugard, World War I and the Amalgamation of Nigeria 1914-1919

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1966 Sir Frederick Lugard, World War I and the Amalgamation of Nigeria 1914-1919 John F. Riddick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Riddick, John F., "Sir Frederick Lugard, World War I and the Amalgamation of Nigeria 1914-1919" (1966). Master's Theses. 3848. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3848 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIR FREDERICK LUGARD, WORLD WAR I. AND - THE AMALGAMATION OF NIGERIA 1914-1919/ by John I<'. Riddick A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August, 1966 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation for the co-operation of the following research institutions: Boston University Library, Boston, Massachusetts Kalamazoo College Library, Kalamazoo, Michigan Michigan State University Library, East Lansing, Michigan Northwestern University Library, Evanston, Illinois The University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan The Western Michigan University Library, Kalamazoo, Michigan I am most grateful for the encouragement, advice, and criticism of' Dr. H. Nicholas Hamner, who directed the entire project. A debt of thanks is also due to Mrs. Ruth Allen, who typed the finished product, and to my wife, who assisted me in every way. -

Download Download

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Administering the Empire, 1801-1968: A Guide to the Records of the Colonial Office in the National Archives of the UK by Mandy Banton http://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/administering-the- empire-1801-1968 DOI: 10.14296/0920.9781912702787 ***** This edition published 2020 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-78-7 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses A Guide to the Records of the Colonial Office in The National Archives of the UK Archives National The Office in of the Colonial to the Records A Guide 1801–1968Administering the Empire, Administering the Empire, 1801-1968 is an indispensable introduction to British colonial rule during Administering the Empire, 1801–1968 the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It provides an essential guide to the records of the British Colonial Office, and those of other departments responsible for colonial administration, which are A Guide to the Records of the Colonial Office in now held in The National Archives of the United Kingdom. The National Archives of the UK As a user-friendly archival guide, Administering the Empire explains the organisation of these records, the information they provide, and how best to explore them using contemporary finding aids. -

Crisis and Conflict Resolution in Brass Province Before 1960

CRISIS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION IN BRASS PROVINCE BEFORE 1960 ONYEJIUWA, CHRISTOPHER IFEANYICHUKWU AND OKAFOR, GERALD IFEANYICHUKWU ABSTRACT This work is aimed at explaining the origin of Brass people and the villages that made up of the present Ijaw nation. It also attempts to give an overview of conflict resolution in Brass province before independence of 1960. Among other things, it attempts to disclose how judicial system in the area became instrumental to boundary disputes and the approaches taken to resolve them. This work made effective use of primary and secondary sources of research methodology. Under the primary sources, interviews were conducted with elderly people, academia and civil servants whereas, under secondary sources, literature that related to the topic were liberally used. In the course of this research, we found out that a lot of administrative blunders took place during the period understudy but were either recorded and lost or deliberately overlooked. Again, reports of some colonial officers which were gotten from the opinions of some prominent Ijaw natives were distorted to favour the colonial government. Also, history of the Brass people was controversial and unclear, thus making research in them more imaginative. Among other problems, we discovered that there was few literature on the judicial practices in the Brass province. INTRODUCTION The Brass Province during the period under study was a Colonial territory of the Great Britain located in the coastal region of what is called South-South on Niger-Delta region of modern day Nigeria. Ab- 78 | International Journal of Humanities initio, the Portuguese were the first Europeans that had contact with the natives based on commerce.