Les Chefferies Traditionnelles Au Nigeria NIGERIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.10, No.3, 2020 Primordial Niger Delta, Petroleum Development in Nigeria and the Niger Delta Development Commission Act: A Food For Thought! Edward T. Bristol-Alagbariya* Associate Dean & Senior Multidisciplinary Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Port Harcourt, NIGERIA; Affiliate Visiting Fellow, University of Aberdeen, UNITED KINGDOM; and Visiting Research Fellow, Centre for Energy, Petroleum & Mineral Law and Policy (CEPMLP), Graduate School of Natural Resources Law, Policy & Management, University of Dundee, Scotland, UNITED KINGDOM * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The historic and geographic ethnic minority Delta region of Nigeria, which may be called the Nigerian Delta region or the Niger Delta region, has been in existence from time immemorial, as other primordial ethnic nationality areas and regions, which were in existence centuries before the birth of modern Nigeria. In the early times, the people of the Niger Delta region established foreign relations between and among themselves, as people of immediate neigbouring primordial areas or tribes. They also established long-distance foreign relations with distant tribes that became parts and parcels of modern Nigeria. The Niger Delta region, known as the Southern Minorities area of Nigeria as well as the South-South geo-political zone of Nigeria, is the primordial and true Delta region of Nigeria. The region occupies a very strategic geographic location between Nigeria and the rest of the world. For example, with regard to trade, politics and foreign relations, the Nigerian Delta region has been strategic throughout history, ranging, for instance, from the era of the Atlantic trade to the ongoing era of petroleum resources development in Nigeria. -

Annual Report of the Colonies. Nigeria 1898

This document was created by the Digital Content Creation Unit University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2010 COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL. No. 284. LAGOS, REPORT FOR 1898. (For Report for 1897, see No. 832.) tyimnti* to totf) tyQum of ^aiclianunt b# OIomman& of pjt fflawtfr December, 1899. 1 LONDON. PRINTED FOE HER MAJESTTS STATIONERY OFPIOB, BY DARLING & SON, LTD., 1-3, GREAT ST THOMAS APOSTLE, 1S.O. And to be purchased, either directly w th- %ny Bookseller, from E'iiiE & SPOTTISWOODE. EAS" TARI>IN'.J- SI: J. FLEET 8?ss*-r, AJ.O. tad 82, ABINODOH STREET, "WEd-*v;n,3I:J.8T S.W.; or JOHN MENZIES & Co., 12, HANOVER STREET, EDINB&BOH, tad DO, WEST ±!ILE STREET, GLASGOW ; or HODGES, FIGGIS, & Co., LIMIT J>, 104, GBJUTTOX grant, A>TOU* 1890. COLONIAL REPORTS. The following, among other, reports relating to Her Majesty's Colonial Possessions have been issued, and may be obtained for a few pence from the sources indicated on the title page :— ANNUAL. No. Colony. Year. 255 Basutoland • • • • • • • • • 1897-98 256 Newfoundland - •»• 1896-97 257 Cocos-Keeling and Christmas Islands 1898 258 British New Guinea ... •» • * • • • • • 1897-98 259 Bermuda • * * • • e • • • 1898 260 Niger.—West African Frontier \ Force 1897-98 261 Jamaica ... • • • ft 262 Barbados .. • • • • • • • • • 1898 263 Falkland Islands • • • • *« * • • * )>t 264 Gambia ... • • • • • • • • • f* 265 St. Helena • • • • • • * • • ft 266 Leeward Islands ... • • • ft 267 St. Lucia... • • • ••• 1* 268 JEP&j x • • • • • • * *» • • • • •«• »•# t'l 269 Tarks and Caicos Islands • * • ••* ••• ft 270 Al£vlt& ••• • • <* • 6-0. • • • ft 271 Gold Coast • • • •0* ft 272 Trinidad • • • «*• • *f 273 Sierra Leone • • • 0 * • • * • ft 274 Ceylon ... • • • ff • • • • • ft 275 British Solomon Islands • • • « ft » • • • 1898-99 276 Gibraltar f • * 1898 277 Bahamas tf 278 British Honduras ...... -

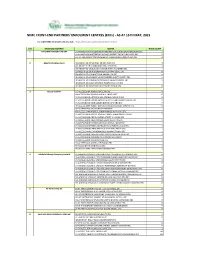

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

The Harem 19Th-20Th Centuries”

Pt.II: Colonialism, Nationalism, the Harem 19th-20th centuries” Week 11: Nov. 27-9; Dec. 2 “Northern Nigeria: from Caliphate to Colony” Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • Early 19th C. Jihad established Sokoto Caliphate: • Uthman dan Fodio • Born to scholarly family (c.1750) • Followed conservative Saharan brotherhood (Qadiriyya) Northern Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1790s – 1804: growing reputation as teacher • Preaching against Hausa Islam: state we left in discussion of Kano Palace18th c. (Nast) • ‘corruption’: illegal imposition various taxes • ‘paganism’: continued practice ‘pre-Islamic’ rituals (especially Bori spirit cult) • Charged political opponent, Emir of Gobir as openly supporting: first ‘target’ of jihad Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1804: beginning of jihad • Long documented correspondence/debate between them • Emir of Gobir did not accept that he was ‘bad Muslim’ who needed to ‘convert’ – dan Fodio ‘disagreed’ • Declared ‘Holy War’ Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • Drew in surrounding regions: why attracted? • marginalization vis-à-vis central Hausa provinces • exploited by excessive taxation • attraction of dan Fodio’s charisma, genuine religious fervour Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1817, Uthman dan Fodio died: • Muhamed Bello (son) took over as ‘caliph’ • nature of jihad changed fundamentally: became one of ‘the heart and mind’ • ‘conquest’ only established fragile boundaries of state • did not create the Islamic regime envisaged by dan Fodio Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • New ‘Islamic state’ carved out of pre-existing Muslim society: needed full legitimization • Key ‘tool’ to shaping new society -- ‘educating people to understand the Revolution’ -- was education Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nana Asma’u (1793 – 1864): - educated daughter of Uthman dan Fodio - fluent in Arabic, Fulfulbe, Hausa, Tamechek [Tuareg] - sister Mohamed Bello Nigeria: 19th-20th C. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Ink 12 2 Full Journal FM 09 Jan.Backup.Fm

Inkanyiso 1 The Journal of Humanities and Social Science ISSN 2077-2815 Volume 12 Number 2 2020 Editor-in-Chief Prof. Dennis N. Ocholla, PhD University of Zululand, [email protected]. Editorial committee Prof. Catherine Addison, Dr. Neil Evans, Prof. Myrtle Hooper, Prof. Thandi Nzama; Prof. Jabulani Thwala Editorial advisory board Johannes Britz, Professor of Information Studies, Provost and Vice-Chancellor, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA – [email protected]. Rafael Capurro, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy and Ethics, Hochschule se Medien (HdM) Stuttgart, Germany – [email protected]. Stephen Edwards, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, University of Zululand, South Africa - [email protected] . Christopher Isike, PhD, Professor of African Politics, African Development and International Relations, University of Pretoria – [email protected] Trywell Kalusopa, PhD, Professor of Records Management, University of Namibia, Namibia - [email protected] Mogomme Masoga, PhD, Professor and Dean , Faculty of Arts, University of Zululand, South Africa - [email protected] Peter Matu, PhD, Professor and Executive Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences and Technology, Technical University of Kenya, Kenya – [email protected] Elliot Mncwango, PhD, Senior Lecturer and Interim Head of the Department of General Linguistics and European Languages, University of Zululand, South Africa – [email protected] . Berrington Ntombela, PhD Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of English, University of Zululand, South Africa – [email protected] -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

The Sinister Political Life of Community

NIGER DELTA ECONOMIES OF VIOLENCE WORKING PAPERS Working Paper No. 3 THE SINISTER POLITICAL LIFE OF COMMUNITY Economies of Violence and Governable Spaces in the Niger Delta, Nigeria Michael Watts Director, Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, USA 2004 Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, USA The United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC, USA Our Niger Delta, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 1 The Sinister Political Life of Community: Economies of Violence and Governable Spaces in the Niger Delta, Nigeria Michael Watts We seek to recover the . life of the community, as neither the “before” nor the “after” picture of any great human transformation. We see “communities” as creatures with an extraordinary and actually . quite sinister political life in the ground of real history. Kelly and Kaplan (2001:199) “Community” is an archetypal keyword in the sense deployed by Raymond Williams (1976). A “binding” word, suturing certain activities and their interpretation, community is also “indicative” (Williams’s term once again) in certain forms of thought. Deployed in the language for at least five hundred years, community has carried a range of senses denoting actual groups (for example “commoners” or “workers”) and connoting specific qualities of social relationship (as in communitas). By the nineteenth century, community was, of course, invoked as a way of talking about much larger issues, about modernity itself. Community—and its sister concepts of tradition and custom—now stood in sharp contrast to the more abstract, instrumental, individuated, and formal properties of state or society in the modern sense. A related shift in usage subsequently occurred in the twentieth century, when community came to refer to a form or style of politics distinct from the formal repertoires of national or local politics. -

Unity in Diversity: a Comparative Study of Selected Idioms in Nembe (Nigeria) and English

Intercultural Communication Studies XXIII: 2 (2014) TEILANYO Unity in Diversity: A Comparative Study of Selected Idioms in Nembe (Nigeria) and English Diri I. TEILANYO University of Benin, Nigeria Abstract: Different linguistic communities have unique ways of expressing certain ideas. These unique expressions include idioms (as compared with proverbs), often being fixed in lexis and structure. Based on assumptions and criticisms of the Sapir-Whorfian Hypothesis with its derivatives of cultural determinism and cultural relativity, this paper studies certain English idioms that have parallels in Nembe (an Ijoid language in Nigeria’s Niger Delta). It is discovered that while the codes (vehicles) of expression are different, the same propositions and thought patterns run through the speakers of these different languages. However, each linguistic community adopts the concepts and nuances in its environment. It is concluded that the concept of linguistic universals and cultural relativity complement each other and provide a forum for efficient communication across linguistic, cultural and racial boundaries. Keywords: Idioms, proverbs, Nembe, English, proposition, equivalence, Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, linguistic universals, cultural relativity 1. Introduction: Language and Culture (Unity or Diversity) The fact that differences in culture are reflected in the patterns of the languages of the relevant cultures has been recognized over time. In this regard, one of the weaknesses modern linguists find in classical (traditional) grammar is the “logical fallacy” (Levin, 1964, p. 47) which assumed “the immutability of language” (Ubahakwe & Obi, 1979, p. 3) on the basis of which attempts were made to telescope the patterns of modern European languages (most of which are at least in past “analytic”) into the structure of the classical languages like Greek and Latin which were largely “synthetic”. -

South – West Zone

South – West Zone Ogun State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08033251216 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Abigi Abisi Main Garage 2 Aiyepe Ikenne Local Government Secretariat, Ikenne 1 3 Aiyepe Ikenne Local Government Secretariat, Ikenne 2 4 Aiyepe Ikenne Ilisan Palace 5 Aiyetoro Ayetoro Palace 6 Ake Itoku Market 7 Ake Ake Palace 8 Ake Osile Palace 9 Ake Olumo Tourist Center 10 Atan Ijebu Igbo (Abusi College) 11 Atan Ago Iwoye (Ebumawe Palace) 12 Atan Atan Local Government Secretariat 13 Atan Alasa Market 14 Atan Oba’s Palace 15 Atan Alaga Market 16 Ewekoro Itori, Near Local Government Secretariat 1 17 Ewekoro Itori, Near Local Government Secretariat 2 18 Ifo Ogs Plaza, Ajuwon 19 Ifo Ijoko Last Bus Stop 20 Ifo Akute Market 21 Ifo Ifo Market 22 Ifo Agbado, Rail Crossing 23 Ifo Agbado/Opeilu, Junction 1 24 Ifo Agbado/Opeilu, Junction 2 25 Ijebu Igbo Oru Garage, Oru 1 26 Ijebu Igbo Station 27 Sagamu Portland Cement Gate 28 Sagamu Moresimi 29 Sagamu NNPC Gate 30 Ota Covenant University Gate 31 Ota Covenant Central Auditorium 32 Ota Covenant University Female Hostel 1 33 Ota Covenant University Male Hostel 1 34 Redeem Camp Redeemers University Gate 35 Redeem Camp Redeemers University Admin Office 36 Redeem Camp Main Gate 37 Ogere Old Toll Gate (Lagos Side) 38 Ogere Old Toll Gate (Ibadan Side) 39 UNAAB University Of Agriculture Gate 40 UNAAB UNAAB Student Building 41 Odogbolu Government College, Odogbolu 42 Osu Ogun State University Gate 43 Osu Ogun State University Main Campus 44 Ijebu Igbo Oru Garage, Oru 2 45 Ilaro Ilaro, Sayedero 46 Ilaro Orita -

Reflections on Alagbariya, Asimini and Halliday-Awusa As Selfless

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.10, No.3, 2020 Natural Law as Bedrock of Good Governance: Reflections on Alagbariya, Asimini and Halliday-Awusa as Selfless Monarchs towards Good Traditional Governance and Sustainable Community Development in Oil-rich Bonny Kingdom Edward T. Bristol-Alagbariya * Associate Dean & Senior Multidisciplinary Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Port Harcourt, NIGERIA; Affiliate Visiting Fellow, University of Aberdeen, UNITED KINGDOM; and Visiting Research Fellow, Centre for Energy, Petroleum & Mineral Law and Policy (CEPMLP), Graduate School of Natural Resources Law, Policy & Management, University of Dundee, Scotland, UNITED KINGDOM * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Oil-rich Ancient Grand Bonny Kingdom, founded before or about 1,000AD, was the economic and political centre of the Ancient Niger Delta region and a significant symbol of African civilisation, before the creation of Opobo Kingdom out of it (in 1870) and the eventual evolution of modern Nigeria (in 1914). The people and houses of this oil-rich Kingdom of the Nigerian Delta region invest more in traditional rulership, based on house system of governance. The people rely more on their traditional rulers to foster their livelihoods and cater for their wellbeing and the overall good and prosperity of the Kingdom. Hence, there is a need for good traditional governance (GTG), more so, when the foundations of GTG and its characteristic features, based on natural law and natural rights, were firmly established during the era of the Kingdom’s Premier Monarchs (Ndoli-Okpara, Opuamakuba, Alagbariya and Asimini), up to the reign of King Halliday-Awusa.