Cassiterite Solubility and Tin Speciation in Supercritical Chloride Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taylor Creek Tin Distrisl

tions such as Paramount Canyon, the veins TaylorCreek tin distrisl- may reach three to four centimeters in width and a few meters in height and length. A dis- seminated cassiterite halo has been noted stratigraphy,structure, around the veins in Squaw Creek. A recently discoveredrhyolite porphyry has andtiming of mineralizationintensely altered the surrounding country rock near NM-59 where the road crossesthe Conti- byTed L. Egglestonand David L Norman,New Mexico lnstitute of Miningand Technology, Socorro, NM nental Divide. This porphyry is locally quartz- sericite altered and contains as much as I go pyrite. Similar intrusives have been mapped Introduction The Taylor Creek tin district is located in by Woodard (1982) southeast of the Taylor Primary tin depositscommonly are found in the north-central Black Range some 80 km Creek region. granitic plutonic environments where the tin west of Truth or Consequences,New Mexico occurs as cassiterite in greisen veins and as (fig. l). Cassiteritenuggets were first found in Regional geology disseminations in altered granite (Taylor, placers (Fries, 1940a). in the district in 1909 The tin-bearing Taylor Creek Rhyolite is 1979).In southwest New Mexico, however, tin Shortly wood tin thereafter, cassiterite and located in the Mogollon-Datil volcanic field, a occurs as cassiterite in hematite-cassiterite were porphyritic found in vein depositsin rhy- mid-Tertiary volcanic field consisting of inter- veins which cut Tertiary rhyolite domes and placer (Hill, olite lavas as well as in deposits mediate to -

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalj of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the , » Commission Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota By DOUGLAS M. SHERllDAN, HAL G. STEPHENS, MORTIMER H. STAATZ and JAMES J. NORTON PEGMATITES AND OTHER PRECAMBRIAN ROCKS IN THE SOUTHERN BLACK HILLS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1957 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.50 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.__________________________________________ 1 Geology Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 1 Peerless pegmatite Continued Location_____________________________________ 1 Chemical composition......____________ 17 History and production________________________ 2 Origin________ ____________________ _. 18 Past and present investigations.__________________ 3 Mineral deposits_____________________________ 21 Acknowledgments__________________________ 4 Mica__ _________ _________________________ 21 Mine workings _____________________________________ -

Cassiterite Recovery from a Sulfide Ore Flotation Tailing by Combined Gravity and Flotation Separations

Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process., 57(1), 2021, 206-215 Physicochemical Problems of Mineral Processing ISSN 1643-1049 http://www.journalssystem.com/ppmp © Wroclaw University of Science and Technology Received August 11, 2020; reviewed; accepted November 29, 2020 Cassiterite recovery from a sulfide ore flotation tailing by combined gravity and flotation separations Limin Zhang, Sultan an Khoso, Mengjie Tian, Wei Sun School of Minerals Processing and Bioengineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China Key Laboratory of Hunan Province for Clean and Efficient Utilization of Strategic Calcium-containing Mineral Resources, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China Corresponding author: [email protected] (Mengjie Tian) Abstract: Cassiterite (SnO2), which is the most important Sn-containing mineral, is extensively found in large quantities in discarded tailings. The recovery of cassiterite from discarded sulfide ore flotation tailings can reduce resource wastage and environmental pollution. The gravity separation technique can recover multiple valuable minerals, such as cassiterite, whose densities considerably differ from those of their associated gangue minerals. However, its recovery efficiency rapidly decreases as the mineral particle grain size decreases. To recover the finer valuable mineral particles from gravity separation tailings, flotation separation can be used as a supplementary method. In this study, the gravity and flotation separation techniques are combined to recover cassiterite from a sulfide ore tailing. The Sn grade and recovery of the final concentrate is 31.40% and 88.05%, respectively, thus indicating a highly efficient recovery of cassiterite by using the combined gravity and flotation separation technique. This study can be an important reference for recovering cassiterite from low-Sn-grade tailings. -

Porphyry Deposits

PORPHYRY DEPOSITS W.D. SINCLAIR Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth St., Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0E8 E-mail: [email protected] Definition Au (±Ag, Cu, Mo) Mo (±W, Sn) Porphyry deposits are large, low- to medium-grade W-Mo (±Bi, Sn) deposits in which primary (hypogene) ore minerals are dom- Sn (±W, Mo, Ag, Bi, Cu, Zn, In) inantly structurally controlled and which are spatially and Sn-Ag (±W, Cu, Zn, Mo, Bi) genetically related to felsic to intermediate porphyritic intru- Ag (±Au, Zn, Pb) sions (Kirkham, 1972). The large size and structural control (e.g., veins, vein sets, stockworks, fractures, 'crackled zones' For deposits with currently subeconomic grades and and breccia pipes) serve to distinguish porphyry deposits tonnages, subtypes are based on probable coproduct and from a variety of deposits that may be peripherally associat- byproduct metals, assuming that the deposits were econom- ed, including skarns, high-temperature mantos, breccia ic. pipes, peripheral mesothermal veins, and epithermal pre- Geographical Distribution cious-metal deposits. Secondary minerals may be developed in supergene-enriched zones in porphyry Cu deposits by weathering of primary sulphides. Such zones typically have Porphyry deposits occur throughout the world in a series significantly higher Cu grades, thereby enhancing the poten- of extensive, relatively narrow, linear metallogenic tial for economic exploitation. provinces (Fig. 1). They are predominantly associated with The following subtypes of porphyry deposits are Mesozoic to Cenozoic orogenic belts in western North and defined according to the metals that are essential to the eco- South America and around the western margin of the Pacific nomics of the deposit (metals that are byproducts or poten- Basin, particularly within the South East Asian Archipelago. -

Tungsten Minerals and Deposits

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Bulletin 652 4"^ TUNGSTEN MINERALS AND DEPOSITS BY FRANK L. HESS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 25 CENTS PER COPY CONTENTS. Page. Introduction.............................................................. , 7 Inquiries concerning tungsten......................................... 7 Survey publications on tungsten........................................ 7 Scope of this report.................................................... 9 Technical terms...................................................... 9 Tungsten................................................................. H Characteristics and properties........................................... n Uses................................................................. 15 Forms in which tungsten is found...................................... 18 Tungsten minerals........................................................ 19 Chemical and physical features......................................... 19 The wolframites...................................................... 21 Composition...................................................... 21 Ferberite......................................................... 22 Physical features.............................................. 22 Minerals of similar appearance................................. -

Heinrich&Candela TOG2 For

Research Collection Book Chapter Fluids and Ore Formation in the Earth's Crust Author(s): Heinrich, Christoph A.; Candela, Philip A. Publication Date: 2014 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000095425 Originally published in: 13, http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.01101-3 Rights / License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library This is the Green Open Access version of: Heinrich C.A., and Candela P.A. (2014) Fluids and Ore Formation in the Earth's Crust. In: Holland H.D. & Turekian K.K. (eds.) Treatise on Geochemistry, 2nd Edition, vol. 13 (Geochemistry of Mineral Deposits, S. D. Scott, ed.), p. 1-28. Original publication see http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.01101-3 Fluids and Ore Formation in the Earth’s Crust Christoph A. Heinrich1 and Philip A. Candela2 1 ETH Zurich, Department of Earth Sciences, and University of Zurich, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Clausiusstr. 25, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Laboratory for Mineral Deposits Research, Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD,20742, USA Synopsis Ore deposits are rock volumes containing selected elements in sufficient concentration and quantity that they can Be extracted economically. Except for Fe and Al, all technically important metals and other elements are scarce, in total constituting less that 1% of the Earth’s crust. Depending on the element and its mineralogy, a 10- to 10,000-fold enrichment is required for economic extraction today. -

The Genetic Association Between Quartz Vein- and Greisen-Type

minerals Article The Genetic Association between Quartz Vein- and Greisen-Type Mineralization at the Maoping W–Sn Deposit, Southern Jiangxi, China: Insights from Zircon and Cassiterite U–Pb Ages and Cassiterite Trace Element Composition Li-Li Chen, Pei Ni *, Bao-Zhang Dai *, Wen-Sheng Li, Zhe Chi and Jun-Yi Pan State Key Laboratory for Mineral Deposits Research, Institute of Geo–Fluids, School of Earth Sciences and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.N.); [email protected] (B.-Z.D.); Tel.: +86-25-8968-0883 (P.N.); +86-25-8368-6649 (B.-Z.D.) Received: 28 May 2019; Accepted: 3 July 2019; Published: 4 July 2019 Abstract: The large-scale Maoping W–Sn deposit in the Gannan metallogenic belt of the eastern Nanling Range, South China, spatially associated with the Maoping granite pluton, hosts total ore reserves of 103,000 t WO3 and 50,000 t Sn. Two different types of mineralization developed in this deposit: Upper quartz vein-type mineralization, mostly within the Cambrian metamorphosed sandstone and slate, and underneath greisen-type mineralization within the Maoping granite. Cassiterites from both types of mineralization coexist with wolframite. Here we report for the first time in situ U–Pb data on cassiterite and zircon of the Maoping deposit obtained by LA-ICP-MS. Cassiterite from quartz vein and greisen yielded weighted average 206Pb/238U ages of 156.8 1.5 Ma ± and 156.9 1.4 Ma, respectively, which indicates that the two types of mineralization formed roughly ± at the same time. In addition, the two mineralization ages are consistent with the emplacement age of the Maoping granite (159.0 1.5 Ma) within error, suggesting a close temporal and genetic link ± between W–Sn mineralization and granitic magmatism. -

Kiiash Journalofafrican Earth Sciences

kiiash JournalofAfrican Earth Sciences. Vol. 28. No. 3. DD. 581-598. 1999 Pergamon a 1999 Eisevier Science Ltd Pll:SO899-5382(99)00033-O All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain 0699.5362199 $- see front matter Mineralogical and geochemical investigation of emerald and beryl mineralisation, Pan-African Belt of Egypt: genetic and exploration aspects H. M. ABDALLA’ and F. H. MOHAMED2 ‘Nuclear Materials Authority, Cairo, Egypt *Geology Department, Faculty of Science, Alexandria University, Egypt ABSTRACT-Mineralogical, geochemical and fluid inclusion studies reveal two favourable environments for the localisation of beryl mineralisations in the Precambrian rocks of Egypt: (1)emerald-schist; and (2) beryl-specialised granitoid associations. Emerald occurs within the mica schists and is typically confined to the Nugrus major shear zone. However, beryl associated with granitoids occurs in pegmatite veins, greisen bodies, and cassiterite quartz veins cutting the granites and the exocontacts of the volcanosedimentary country rocks. Compositionally, emerald is of octahedral type and its cell edge is lengthened along the a-axis, while beryl associated with granitoids is normal in composition and structural constants. Emerald is thought to be formed as the result of epitactic nucleation of Be, Al and alkali-rich solutions on the mica of the schist country rocks. Fluid inclusion studies show that the solutions are saline (8-22 wt% NaCl equiv.) and the reactions proceeded in the temperature range 260-382OC. On the other hand, aqueous inclusions in beryl associated with granitoids show the following sequence of formation with decreasing temperatures and salinities: beryl pegmatite (320-480°C and 7-16 wt% NaCl equiv.)+greisen bodies (190-400°C and 4-7 wt% NaCl equiv.)+cassiterite-quartz veins (1 90-380°C and 2-4 wt% NaCl equiv.). -

Chromium, Iron, Gold and Manganese in Amapá and Northern Pará, Brazil Wilson Scarpelli1* , Elio Hiromi Horikava2

DOI: 10.1590/2317-4889201820180026 ARTICLE Chromium, iron, gold and manganese in Amapá and northern Pará, Brazil Wilson Scarpelli1* , Elio Hiromi Horikava2 ABSTRACT: Information is presented on the geology and mineral deposits in greenstone belts and mafic-ultramafic complexes in Amapá and northern Pará, with the emphasis in iron, gold, manganese, and chromium. At Santa Maria, the Vila Nova Group presents deposits of iron and gold, the latter in carbonatic metasediments crossed by a north-south shear. The group is intruded by the Bacuri Mafic-Ultramafic Complex, with mineable deposits of chromite and magnetite. The overlaying 21 Grande Formation presents minor gold mineralization. At Serra das Coambas there is a significant show of iron formation, and, at its flank, the 21 Grande Formation presents extensive areas exploited by gold miners for gold. Serra do Ipitinga, in Pará, contains the greatest units of iron formation of the area, accompanied by frequent shows of alluvial and primary gold mineralization. The distribution of manganesiferous metasediments identified by mining companies indicate that they were deposited in an about 90 km long narrow basin oriented to northwest, with Serra do Navio near its center. The exposures of iron formation indicate that they were deposited on a belt greater than 350 km long and 100 km wide, oriented and still open to northeast, covering areas of different ages of metamorphism and tectonical stabilization. KEYWORDS: greenstone belts; mafic-ultramafic complexes; manganese sedimentary basin; iron sedimentary basin; patterns of gold mineralization. INTRODUCTION in the ages of the younger granitic intrusives, variations in the stratigraphy of the greenstone belts, locally distinct Following our description of the geology of the Amapari metamorphic phase, alkaline intrusives at west, and, quite Greenstone Belt near Serra do Navio, Amapá, and its deposits important, a layered mafic-ultramafic intrusive, with mag- of manganese, iron and gold (Scarpelli & Horikava 2017), matic seams of chromite. -

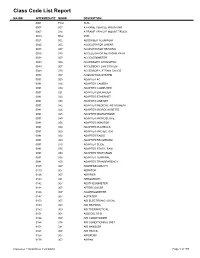

Class Code List Report

Class Code List Report MAJOR INTERMEDIATE MINOR DESCRIPTION 0001 FOU 3676 0007 007 A FRAME VEHICLE MOUNTING 0007 014 A FRAME VEHICLE MOUNT TRUCK 0010 BAC 0555 0021 002 ABSORBER ALUMINUM 0035 005 ACCELERATOR LINEAR 0035 007 ACCELERATOR READING 0035 015 ACCELERATOR NETWORK PATH 0038 007 ACCELEROMETER 0049 004 ACCESSORY CRYOGENIC 0049 007 ACCESSORY LAN SYSTEM 0049 010 ACCESSORY, STRAIN GAUGE 0058 007 ACQUISITION SYSTEM 0091 003 ADAPTER AC 0091 014 ADAPTER CAMERA 0091 018 ADAPTER COMPUTER 0091 021 ADAPTER ENLARGER 0091 023 ADAPTER ETHERNET 0091 038 ADAPTER LINE SET 0091 042 ADAPTER MEDICAL INSTRUMENT 0091 044 ADAPTER MICROCASSETTE 0091 045 ADAPTER MICROPHONE 0091 049 ADAPTER MICROSCOPE 0091 056 ADAPTER MONITOR 0091 058 ADAPTER PLAYBACK 0091 060 ADAPTER PROJECTOR 0091 062 ADAPTER RADIO 0091 063 ADAPTER RECORDING 0091 070 ADAPTER SLIDE 0091 075 ADAPTER STATIC RAM 0091 090 ADAPTER TELEVISION 0091 095 ADAPTER TERMINAL 0091 100 ADAPTER TRANSPARENCY 0105 007 ADDRESSOGRAPH 0119 007 AERATOR 0126 007 AERIFIER 0140 021 AEROGRAPH 0142 007 AESTHESIOMETER 0144 007 AFTERCOOLER 0146 007 AGGREGOMETER 0147 007 AGITATOR 0150 007 AID ELECTRONIC VOCAL 0150 008 AID HEARING 0150 009 AID THERAPUTICAL 0151 004 AIDE DELTOID 0154 007 AIR CONDITIONER 0154 014 AIR CONDITIONING UNIT 0154 021 AIR HANDLER 0161 007 AIR TRACK 0168 007 AIRBRUSH 0179 007 AIRPAK Printed on 11/5/2010 at 1:23:00PM Page 1 of 139 MAJOR INTERMEDIATE MINOR DESCRIPTION 0182 007 AIRPLANE 0189 003 ALARM AUTO 0189 007 ALARM BURGLAR 0189 014 ALARM FIRE 0189 021 ALARM INTRUDER 0189 022 ALARM SYSTEM ERROR -

Summaries of Important Areas for Mineral Investment and Production

Chapter 5B. Analysis of Imaging Spectrometer Data for the Daykundi Area of Interest By Todd M. Hoefen, Daniel H. Knepper, Jr. and Stuart A. Giles Abstract Imaging spectrometer data collected over the Daykundi area of interest (AOI) in central Afghanistan were analyzed with spectroscopic methods to identify the occurrence of selected surficial material classes. Absorption features in the spectra of HyMap data were compared to a reference library of spectra of known materials. The HyMap data for the Daykundi AOI show good correlation to the various lithologic units of the region. The calcite, calcite + clays/micas, muscovite and illite classes cover most of the AOI. However, spatially contiguous patterns of dolomite, chlorite or epidote, montmorillonite, serpentine and kaolinite + muscovite/clay/calcite are mapped throughout the region. In the iron-bearing minerals map, the Fe2+ Fe3+ Type 2, goethite classes, Fe3+ Type 1, and Fe-hydroxide classes dominate the AOI, with smaller groupings of hematite and epidote occurring in several areas. The muscovite, illite, dolomite, serpentine, and Fe2+ Fe3+ Type 2 classes are all associated with different geologic units in the area. Most of the known mineral occurrences in the AOI are small or lack diagnostic spectral features, which makes them difficult to detect with the HyMap data. Therefore, very few of the unnamed, unknown or unclassified prospects can be correlated back to classes mapped with the HyMap sensor. For the larger prospects, the HyMap mapping results can usually be correlated back to the gangue minerals, deposit mineralogy or minerals associated with the host lithology. 5B.1 Introduction Previous U.S. -

Cassiterite Sno2 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal

Cassiterite SnO2 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal. Point Group: 4/m 2/m 2/m. Crystals short to long prismatic k [001], with {110} and {100} well developed, terminated by steep pyramidal forms, to 10 cm; less commonly pyramidal. In radially fibrous botryoidal crusts and concretionary masses; coarse to fine granular, massive. Twinning: Very common on {011}, as contact and penetration twins, geniculated; lamellar. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {100} imperfect, {110} indistinct; partings on {111} or {011}. Fracture: Subconchoidal to uneven. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 6–7 VHN = 1239–1467 (200 g load). D(meas.) = 6.98–7.01 D(calc.) = 6.993 Optical Properties: Transparent when light colored, dark material nearly opaque; commonly zoned. Color: Black, brownish black, reddish brown, red, yellow, gray, white; rarely colorless; in transmitted light, colorless to brown, orange, yellow, green; in reflected light, light gray with white to brownish internal reflections. Streak: White, pale brown, pale gray. Luster: Adamantine to adamantine metallic, splendent; may be greasy on fractures. Optical Class: Uniaxial (+); anomalously biaxial. Pleochroism: Strong to very weak; yellow, red, brown. Absorption: E > O. ω = 1.990–2.010 = 2.093–2.100 2V(meas.) = 0◦–38◦ Anisotropism: Strong. R1–R2: (400) 11.7–13.2, (420) 11.6–13.0, (440) 11.5–12.8, (460) 11.4–12.6, (480) 11.3–12.5, (500) 11.2–12.4, (520) 11.0–12.2, (540) 11.0–12.1, (560) 10.9–12.0, (580) 10.9–12.0, (600) 10.8–12.0, (620) 10.8–12.0, (640) 10.7–12.0, (660) 10.7–12.0, (680) 10.6–12.0, (700) 10.6–12.0 Cell Data: Space Group: P 42/mnm (synthetic).