∫ K∫ K∫ Chaplygin Equations and an Infinite Set of Uniformly Divergent Gas-Dynamics Equations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanic History of the Imbrium Basin: a Close-Up View from the Lunar Rover Yutu

Volcanic history of the Imbrium basin: A close-up view from the lunar rover Yutu Jinhai Zhanga, Wei Yanga, Sen Hua, Yangting Lina,1, Guangyou Fangb, Chunlai Lic, Wenxi Pengd, Sanyuan Zhue, Zhiping Hef, Bin Zhoub, Hongyu Ling, Jianfeng Yangh, Enhai Liui, Yuchen Xua, Jianyu Wangf, Zhenxing Yaoa, Yongliao Zouc, Jun Yanc, and Ziyuan Ouyangj aKey Laboratory of Earth and Planetary Physics, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China; bInstitute of Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; cNational Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100012, China; dInstitute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; eKey Laboratory of Mineralogy and Metallogeny, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China; fKey Laboratory of Space Active Opto-Electronics Technology, Shanghai Institute of Technical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200083, China; gThe Fifth Laboratory, Beijing Institute of Space Mechanics & Electricity, Beijing 100076, China; hXi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710119, China; iInstitute of Optics and Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610209, China; and jInstitute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Science, Guiyang 550002, China Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved March 24, 2015 (received for review February 13, 2015) We report the surface exploration by the lunar rover Yutu that flows in Mare Imbrium was obtained only by remote sensing from landed on the young lava flow in the northeastern part of the orbit. On December 14, 2013, Chang’e-3 successfully landed on the Mare Imbrium, which is the largest basin on the nearside of the young and high-Ti lava flow in the northeastern Mare Imbrium, Moon and is filled with several basalt units estimated to date from about 10 km south from the old low-Ti basalt unit (Fig. -

Actual Problems Актуальные Проблемы

АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК АВИАЦИИ И ВОЗДУХОПЛАВАНИЯ РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ КОСМОНАВТИКИ ИМ. К.Э.ЦИОЛКОВСКОГО ACADEMY OF AVIATION AND AERONAUTICS SCIENCES RUSSIAN ASTRONAUTICS ACADEMY OF K.E.TSIOLKOVSKY'S NAME СССР 7 195 ISSN 1727-6853 12.04.1961 АКТУАЛЬНЫЕ ПРОБЛЕМЫ АВИАЦИОННЫХ И АЭРОКОСМИЧЕСКИХ СИСТЕМ процессы, модели, эксперимент 2(39) 2014 RUSSIAN-AMERICAN SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF AVIATION AND AEROSPACE SYSTEMS processes, models, experiment УРНАЛ УЧНЫЙ Ж О-АМЕРИКАНСКИЙ НА ОССИЙСК Р Казань Daytona Beach А К Т УА Л Ь Н Ы Е П Р О Б Л Е М Ы А В И А Ц И О Н Н Ы Х И А Э Р О К О С М И Ч Е С К И Х С И С Т Е М Казань, Дайтона Бич Вып. 2 (39), том 19, 1-206, 2014 СОДЕРЖАНИЕ CONTENTS Г.В.Новожилов 1 G.V.Novozhilov К 120-летию авиаконструктора To the 120-th Anniversary of Сергея Владимировича Ильюшина Sergey Vladimirovich Ilyushin А.Болонкин 14 A.Bolonkin Использование энергии ветра Utilization of wind energy at high больших высот altitude Эмилио Спедикато 46 Emilio Spedicato О моделировании взаимодействия About modelling interaction of Earth Земли с крупным космическим with large space object: the script with объектом: сценарий взрыва Фаэтона explosion of Phaeton and the sub- и последующей эволюции sequent evolution of Mankind (part II) Человечества (часть II) М.В.Левский 76 M.V.Levskii Оптимальное по времени The time-optimal control of motion of a управление движением spacecraft with inertial executive космического аппарата с devices инерционными исполнительными органами В.А.Афанасьев, А.С.Мещанов, 99 V.A.Afanasyev, A.S.Meshchanov, Е.Ю.Самышева -

Application of Tetraether Membrane Lipids As Proxies for Continental Climate

Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Application of tetraether membrane lipids as proxies for continental climate reconstruction in Iberian and Siberian lakes Marina Escala Pascual Tesi doctoral Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Application of tetraether membrane lipids as proxies for continental climate reconstruction in Iberian and Siberian lakes Memòria presentada per Marina Escala Pascual per optar al títol de Doctor per la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, sota la direcció del doctor Antoni Rosell Melé. Marina Escala Pascual Abril 2009 Cover photograph: Lake Baikal (Jens Klump, Continent Project) Als meus pares i al meu germà. INDEX Acknowledgements .................................................................................i Abstract .................................................................................................iii Resum ....................................................................................................iv Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1. Paleoclimate and biomarker proxies ....................................................3 1.2. Distribution of Archaea in freshwater environments ........................5 1.3. Origin and significance of GDGTs .......................................................9 1.4. Calibration of GDGT-based proxies ..................................................14 1.5. Objective and outline of this thesis ....................................................19 Chapter 2 Methodology 2.1. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Deep Carbon Emissions from Volcanoes Michael R

Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry Vol. 75 pp. 323-354, 2013 11 Copyright © Mineralogical Society of America Deep Carbon Emissions from Volcanoes Michael R. Burton Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia Via della Faggiola, 32 56123 Pisa, Italy [email protected] Georgina M. Sawyer Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, Université Blaise Pascal 5 rue Kessler, 63038 Clermont Ferrand, France and Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia Via della Faggiola, 32 56123 Pisa, Italy Domenico Granieri Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia Via della Faggiola, 32 56123 Pisa, Italy INTRODUCTION: VOLCANIC CO2 EMISSIONS IN THE GEOLOGICAL CARBON CYCLE Over long periods of time (~Ma), we may consider the oceans, atmosphere and biosphere as a single exospheric reservoir for CO2. The geological carbon cycle describes the inputs to this exosphere from mantle degassing, metamorphism of subducted carbonates and outputs from weathering of aluminosilicate rocks (Walker et al. 1981). A feedback mechanism relates the weathering rate with the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere via the greenhouse effect (e.g., Wang et al. 1976). An increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations induces higher temperatures, leading to higher rates of weathering, which draw down atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Ber- ner 1991). Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are therefore stabilized over long timescales by this feedback mechanism (Zeebe and Caldeira 2008). This process may have played a role (Feulner et al. 2012) in stabilizing temperatures on Earth while solar radiation steadily increased due to stellar evolution (Bahcall et al. 2001). In this context the role of CO2 degassing from the Earth is clearly fundamental to the stability of the climate, and therefore to life on Earth. -

Nd AAS Meeting Abstracts

nd AAS Meeting Abstracts 101 – Kavli Foundation Lectureship: The Outreach Kepler Mission: Exoplanets and Astrophysics Search for Habitable Worlds 200 – SPD Harvey Prize Lecture: Modeling 301 – Bridging Laboratory and Astrophysics: 102 – Bridging Laboratory and Astrophysics: Solar Eruptions: Where Do We Stand? Planetary Atoms 201 – Astronomy Education & Public 302 – Extrasolar Planets & Tools 103 – Cosmology and Associated Topics Outreach 303 – Outer Limits of the Milky Way III: 104 – University of Arizona Astronomy Club 202 – Bridging Laboratory and Astrophysics: Mapping Galactic Structure in Stars and Dust 105 – WIYN Observatory - Building on the Dust and Ices 304 – Stars, Cool Dwarfs, and Brown Dwarfs Past, Looking to the Future: Groundbreaking 203 – Outer Limits of the Milky Way I: 305 – Recent Advances in Our Understanding Science and Education Overview and Theories of Galactic Structure of Star Formation 106 – SPD Hale Prize Lecture: Twisting and 204 – WIYN Observatory - Building on the 308 – Bridging Laboratory and Astrophysics: Writhing with George Ellery Hale Past, Looking to the Future: Partnerships Nuclear 108 – Astronomy Education: Where Are We 205 – The Atacama Large 309 – Galaxies and AGN II Now and Where Are We Going? Millimeter/submillimeter Array: A New 310 – Young Stellar Objects, Star Formation 109 – Bridging Laboratory and Astrophysics: Window on the Universe and Star Clusters Molecules 208 – Galaxies and AGN I 311 – Curiosity on Mars: The Latest Results 110 – Interstellar Medium, Dust, Etc. 209 – Supernovae and Neutron -

Evidence for Crater Ejecta on Venus Tessera Terrain from Earth-Based Radar Images ⇑ Bruce A

Icarus 250 (2015) 123–130 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Evidence for crater ejecta on Venus tessera terrain from Earth-based radar images ⇑ Bruce A. Campbell a, , Donald B. Campbell b, Gareth A. Morgan a, Lynn M. Carter c, Michael C. Nolan d, John F. Chandler e a Smithsonian Institution, MRC 315, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, United States b Cornell University, Department of Astronomy, Ithaca, NY 14853-6801, United States c NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Mail Code 698, Greenbelt, MD 20771, United States d Arecibo Observatory, HC3 Box 53995, Arecibo 00612, Puerto Rico e Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, MS-63, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, United States article info abstract Article history: We combine Earth-based radar maps of Venus from the 1988 and 2012 inferior conjunctions, which had Received 12 June 2014 similar viewing geometries. Processing of both datasets with better image focusing and co-registration Revised 14 November 2014 techniques, and summing over multiple looks, yields maps with 1–2 km spatial resolution and improved Accepted 24 November 2014 signal to noise ratio, especially in the weaker same-sense circular (SC) polarization. The SC maps are Available online 5 December 2014 unique to Earth-based observations, and offer a different view of surface properties from orbital mapping using same-sense linear (HH or VV) polarization. Highland or tessera terrains on Venus, which may retain Keywords: a record of crustal differentiation and processes occurring prior to the loss of water, are of great interest Venus, surface for future spacecraft landings. -

Theoretical Study on Thermal Release of Helium-3 in Lunar Ilmenite

minerals Article Theoretical Study on Thermal Release of Helium-3 in Lunar Ilmenite Hongqing Song 1,*, Jie Zhang 1, Yueqiang Sun 2, Yongping Li 2, Xianguo Zhang 2, Dongyu Ma 1 and Jue Kou 1 1 School of Civil and Resource Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (J.K.) 2 National Space Science Center, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing 100190, China; [email protected] (Y.S.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (X.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-010-82376239 Abstract: The in-situ utilization of lunar helium-3 resource is crucial to manned lunar landings and lunar base construction. Ilmenite was selected as the representative mineral which preserves most of the helium-3 in lunar soil. The implantation of helium-3 ions into ilmenite was simulated to figure out the concentration profile of helium-3 trapped in lunar ilmenite. Based on the obtained concentration profile, the thermal release model for molecular dynamics was established to investigate the diffusion and release of helium-3 in ilmenite. The optimal heating temperature, the diffusion coefficient, and the release rate of helium-3 were analyzed. The heating time of helium-3 in lunar ilmenite under actual lunar conditions was also studied using similitude analysis. The results show that after the implantation of helium-3 into lunar ilmenite, it is mainly trapped in vacancies and interstitials of ilmenite crystal and the corresponding concentration profile follows a Gaussian distribution. -

Apollo 17 Index: 70 Mm, 35 Mm, and 16 Mm Photographs

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) Preparation, Scanning, Editing, and Conversion to Adobe Portable Document Format (PDF) by: Ronald A. Wells University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 May 2000 A P O L L O 1 7 I N D E X 7 0 m m, 3 5 m m, A N D 1 6 m m P H O T O G R A P H S M a p p i n g S c i e n c e s B r a n c h N a t i o n a l A e r o n a u t i c s a n d S p a c e A d m i n i s t r a t i o n J o h n s o n S p a c e C e n t e r H o u s t o n, T e x a s APPROVED: Michael C . -

Floris Heyne Joel Meter Simon Phillipson Delano Steenmeijer

Floris Heyne Joel Meter Simon Phillipson Delano Steenmeijer Edited by Neil Pearson With a special foreword by Apollo 7 astronaut Walt Cunningham “When you get back… you will be a national hero. But your photographs… they will live forever. Your only key to immortality is the quality of your photography.” Richard W. Underwood NASA Chief of Photography for Mercury, Gemini and Apollo 4 Small steps. Giant leaps. The English word ‘photograph’ is made up of the The early exploration of space is one such historical ancient Greek words ‘photos’ and ‘graphos’ which event, unrivaled among humanity’s achievements. literally mean ‘light writing’. At the time of the Apollo Fortunately space travelers were able to bring back program, that meant exposing a chemically-treated beautiful, moving and instantly recognizable images film to patterns of light and it was this process which to depict it. Those images add a new understanding made it possible to seize moments in time and share to what it means to be human, what it means to them with the world. live on a delicate little orb circling the Sun since time immemorial. A single photograph can tell a story to billions of people. It transcends language barriers, physical Not only did Apollo bring us this photographic barriers and requires no prior knowledge of testimony but many major advancements in the subject. This is the beauty of photography: photographic technology date back to the extensive it reaches out to all people and everybody can research and engineering that was part of the hugely intuitively understand its form and content. -

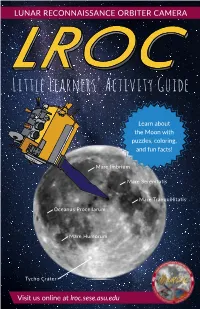

Little Learners' Activity Guide

LUNAR RECONNAISSANCE ORBITER CAMERA Little Learners’ Activity Guide Learn about the Moon with puzzles, coloring, and fun facts! Mare Imbrium Mare Serenitatis Mare Tranquillitatis Oceanus Procellarum Mare Humorum Tycho Crater Visit us online at lroc.sese.asu.edu Online resources Additional information and content, including supplemental learning activities, can be accessed at the following online locations: 1. Little Learners’ Activity Guide: lroc.sese.asu.edu/littlelearners 2. LROC website: lroc.sese.asu.edu 3. Resources for teachers: lroc.sese.asu.edu/teach 4. Learn about the Moon’s history: lroc.sese.asu.edu/learn 5. LROC Lunar Quickmap 3D: quickmap.lroc.asu.edu Copyright 2018, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera i Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Fun Facts for Beginners • The Moon is 363,301 kilometers (225,745 miles) from the Earth. • The surface area of the Moon is almost as large as the continent of Africa. • It takes 27 days for the Moon to orbit around the Earth. • The farside is the side of the Moon we cannot see from Earth. • South Pole Aitken is the largest impact basin on the lunar farside. • Impact basins are formed as the result of impacts from asteroids or comets and are larger than craters. • Regolith is a layer of loose dust, dirt, soil, and broken rock deposits that cover solid rock. • The two main types of rock that make up the Moon’s crust are anorthosite and basalt. • A person weighing 120 lbs on Earth weighs 20 lbs on the Moon because gravity on the Moon is 1/6 as strong as on Earth. -

July 2019 Medicine’S Lunar Legacies • René T

OslerianaA Medical Humanities Journal-Magazine Volume 1 • July 2019 Medicine’s Lunar Legacies • René T. H. Laennec Walter R. Bett • Leonardo da Vinci OslerianaA Medical Humanities Journal-Magazine Editor-in-Chief Nadeem Toodayan MBBS Associate Editor Zaheer Toodayan MBBS Corrigendum: As indicated in the introductory piece to this journal and in footnotes to their respective articles, both editors are Basic Physician Trainees and therefore registered members of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP). In the initial printing of this volume (on this inner cover and on page 5) the postnominal of ‘MRACP’ was used to refer to the editors’ membership status. This postnominal was first applied to the Edi- tor-in-Chief in formal correspondence from The Osler Club of London. Subsequent discussions with the RACP have confirmed that the postnominal is not formally endorsed by the College for trainee members and so it has been removed in this digital edition. Osleriana – Volume 1 Published July 2019 © The William Osler Society of Australia & New Zealand (WOSANZ) e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, print, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of WOSANZ or the individual author(s). Permission to reproduce any copyrighted images used in this publication must be obtained from the appropriate rightsholder(s). Please contact WOSANZ for further information as required. Privately printed in Brisbane, Queensland, by Clark & Mackay Printers. Journal concept and WOSANZ logo by Nadeem Toodayan. Journal design and layout by Zaheer Toodayan.