Floris Heyne Joel Meter Simon Phillipson Delano Steenmeijer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Human and Machine in Spaceflight

Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight David A. Mindell The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email [email protected] This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mindell, David A. Digital Apollo : human and machine in spaceflight / David A. Mindell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-13497-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Human-machine systems. 2. Project Apollo (U.S.)—History. 3. Astronautics—United States—History. 4. Manned spaceflight—History. I. Title. TA167.M59 2008 629.47 04—dc22 2007032255 10987654321 Index Accelerometers, 1 control and, 19–22 Apollo program and, 97, 109–110, 119, 132, F-80 Shooting Star, 45 174, 194, 201 F-104 Starfighter, 45 AC Spark Plug, 110, 127, 134, 137 SR-71, 45 Adams, Mike, 59–61 stability and, 19–22 Adaptive control systems, 57–61, 77 U-2, 45 AGC (Apollo guidance computer), 259 X-1, 44, 46 Apollo 4 and, 174–175 X-15, 6 (see also X-15) Apollo 5 and, 175 Air-pressure gauges, 24 Apollo 7 and, 177 Aldrin, Edwin ‘‘Buzz,’’ 1–4, 8, 86 astronaut input and, 159 Eagle and, 217–232 -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

ORION Flight Test Dec

December 2014 Vol. 1 No. 9 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Kennedy Space Center’s ORION Flight Test Dec. 4, 7:05 a.m. #imonboard Colin Baker http://go.nasa.gov/11r6OeO Lou Ferrigno Nichelle Nichols http://go.nasa.gov/1xlmT2f http://go.nasa.gov/11r7fWA Erin Gray John Barrowman http://go.nasa.gov/1AIE28z Austin St. John http://go.nasa.gov/1xlmT2f http://go.nasa.gov/1AIERyd 2 SPACEPORT Magazine SPACEPORT Magazine 3 International Space MARS Education Technology Solar System History Station (ISS) KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S NASA’S SPACEPORT MAGAZINE LAUNCH SCHEDULE CONTENTS Date: Dec. 4 - 7:05 a.m. EST ...................Orion ready for first test flight Mission: NASA’s Orion 7 spacecraft will launch atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket from Cape 9 ...................Flight Test to carry mementos, inspirational items Canaveral Air Force Stationís Space Launch Complex 37. The Orion Flight Test will evaluate 14 ................IT Advance Concepts Lab changing way IT is done launch and high speed re-entry systems such as avionics, attitude control, parachutes and 22 ................Research ready for SpaceX CRS-5 mission the heat shield. Date: Dec. 16, 2014 - 27 ................Tanzanian teen hopes to become astronaut 2:31 p.m. EST Mission: Launching from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, 30 ................New animation follows long, strange trip of Bennu SpaceX CRS-5 will deliver cargo and crew supplies to the International Space Station. It 33 ................175-ton crane undergoes upgrades also will carry CATS, a laser instrument to measure clouds and the location and distribution 36 ................Ceremony honors fallen astronaut of pollution, dust, smoke and other particulates in the I am the range master at the NASA Protective Services Training atmosphere. -

Deep Carbon Emissions from Volcanoes Michael R

Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry Vol. 75 pp. 323-354, 2013 11 Copyright © Mineralogical Society of America Deep Carbon Emissions from Volcanoes Michael R. Burton Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia Via della Faggiola, 32 56123 Pisa, Italy [email protected] Georgina M. Sawyer Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, Université Blaise Pascal 5 rue Kessler, 63038 Clermont Ferrand, France and Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia Via della Faggiola, 32 56123 Pisa, Italy Domenico Granieri Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia Via della Faggiola, 32 56123 Pisa, Italy INTRODUCTION: VOLCANIC CO2 EMISSIONS IN THE GEOLOGICAL CARBON CYCLE Over long periods of time (~Ma), we may consider the oceans, atmosphere and biosphere as a single exospheric reservoir for CO2. The geological carbon cycle describes the inputs to this exosphere from mantle degassing, metamorphism of subducted carbonates and outputs from weathering of aluminosilicate rocks (Walker et al. 1981). A feedback mechanism relates the weathering rate with the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere via the greenhouse effect (e.g., Wang et al. 1976). An increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations induces higher temperatures, leading to higher rates of weathering, which draw down atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Ber- ner 1991). Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are therefore stabilized over long timescales by this feedback mechanism (Zeebe and Caldeira 2008). This process may have played a role (Feulner et al. 2012) in stabilizing temperatures on Earth while solar radiation steadily increased due to stellar evolution (Bahcall et al. 2001). In this context the role of CO2 degassing from the Earth is clearly fundamental to the stability of the climate, and therefore to life on Earth. -

The Apollo 11 Drive Tubes, 24 Mar 1978

THE APOLLO 11 DRIVE TUBES Dissection and description by Judith H. Allton 24 r~arch 1978 i' PROCEDURES AND METHODS OF STUDY 11.1.1 l. Lunar Surface Procedures and Sampling Rationale 1 .. ...... 2. Cari ng Hardware . ... .•. .. ..•.. ..... .... ...... ..... 3 3. Initial Processing in the BioPreparation Laboratory.. 3 4. Initial Weights and Sample Numbering •••••••••••••••• 3 5. Subsequent History of Handling •••••••••••••••••••••• 4 6. Allocations Prior to Final Dissection ••••••••••••••• 4 7. Dissection Procedure ..... ......................•.... 5 8. Compos i ti ona1 Descri ptions Used for >1 mm Fragments .. 6 9. Analysis of Data ......•..•.••.•...•••.••.•..••••••.. 6 10. 10004 Dissection Procedure Notes .................... 8 11. 10005 Dissection Procedure Notes •••••••••••••••••••• 9 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION •••••••••••••• 10 1. Preservation of Lunar Stratigraphy.................. 10 A. 10004 Initial Core Description ............... 10 B. 10005 Initial Core Description ••••••••••••••• 10 C. 10004 1977 Core Description ................. 11 D. 10005 1977 Core Description ••••••••••••••••• 12 2. Description of Units 10004 •••••••.••••••••••••••••• 14 3. Description of Units 10005 •••.••••••••••••••••••••• 16 4. Comparison of 10004 and 10005 .............. ...... .... 16 WORKS CITED IN TEXT ••••••••••••••••• 18 APPENDIX ..••••.•••.•••..••.•..•••••. 20 /' ' ____ II.l.i \\ \ II.l.ii LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES IN TEXT Figure 1. Map of Landing Site ................................. 11.1.2 2. Core 10004 Designation of Intervals ••••••••••••••••• 7 3. Distribution of Some Rock Types in Core 10004 •••••.• 14 By Weight Content 4. Distribution of Some Rock Types in Core 10005 ...... 15 By Weight Content Table 1. Weight Percent Composition of >1 mm Fraction. 17 A Comparison of 10004 and 10005 APPENDIX Figure 5. Size Analysis of Apollo 11 Fines .................... 21 Table 2. Raw Data for Core 10004 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 22 3. Raw Data for Core 10005 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 23 4. Drive Tube 10004 Sample Location Information ••••••• 24 5. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Abstracts from the Fifth European Workshop on Astrobiology EANA

International Journal of Astrobiology 5 (1): 67–88 (2006) Printed in the United Kingdom 67 doi:10.1017/S1473550406002849 f 2006 Cambridge University Press Abstracts from the Fifth European Workshop on Astrobiology EANA – European Astrobiology Network Association 10–12 October 2005 Budapest, Hungary Early Stars and Stellar Environments Oral Presentations The UV radiation environment in the Solar System Setting a scene: before another Earth will be found A. Hanslmeier(1), M. Vazquez(2), H. Lammer(3), M. Khodachenko(3) E. Szuszkiewicz(1,2), J. C. B. Papaloizou(3,4) (1) Institut fu¨r Physik, Geophysik Astrophysik Meteorologie, Univ.- (1) Institute of Physics, University of Szczecin, Poland; (2) Centre for Platz 5, A-8010 Graz, Austria; (2) Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, Advanced Studies in Astrobiology and Related Topics, Szczecin, C/Vı´aLa´ctea s/n, E-38200, La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain; (3) Austrian Poland; (3) Astronomy Unit, Queen Mary, University of London, Academy of Science Space Research Institute Schmiedlstraße 6, A-8042 England; (4) Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Graz, Austria Physics, Centre for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge, England The UV radiation environment in the Solar System is dominated of The increasing number of extrasolar multi-planet systems, their diver- course by the Sun. Since the early Sun radiated more intensely in the sity, and dynamical complexities provide a strong motivation to study short wavelength range, the influence of this radiation to the early the evolution and stability of such systems. One of the most important planets and to the formation of early planetary atmospheres as well as features connected with planetary system evolution is the occurrence of to the evolution of life on Earth and possibly other planets has to be mean motion resonances, which may relate to conditions at the time of considered in detail. -

Apollo 17 Index: 70 Mm, 35 Mm, and 16 Mm Photographs

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) Preparation, Scanning, Editing, and Conversion to Adobe Portable Document Format (PDF) by: Ronald A. Wells University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 May 2000 A P O L L O 1 7 I N D E X 7 0 m m, 3 5 m m, A N D 1 6 m m P H O T O G R A P H S M a p p i n g S c i e n c e s B r a n c h N a t i o n a l A e r o n a u t i c s a n d S p a c e A d m i n i s t r a t i o n J o h n s o n S p a c e C e n t e r H o u s t o n, T e x a s APPROVED: Michael C . -

On the Moon with Apollo 16. a Guidebook to the Descartes Region. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 062 148 SE 013 594 AUTHOR Simmons, Gene TITLE On the Moon with Apollo 16. A Guidebook to the Descartes Region. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO NASA-EP-95 PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 92p. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. 20402 (Stock Number 3300-0421, $1.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Technology; Astronomy; *Lunar Research; Resource Materials; Scientific Research; *Space Sciences IDENTIFIERS NASA ABSTRACT The Apollo 16 guidebook describes and illustrates (with artist concepts) the physical appearance of the lunar region visited. Maps show the planned traverses (trips on the lunar surface via Lunar Rover); the plans for scientific experiments are described in depth; and timelines for all activities are included. A section on uThe Crewn is illustrated with photos showing training and preparatory activities. (Aathor/PR) ON THE MOON WITH APOLLO 16 A Guidebook to the Descartes Region U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- grIl INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION on POLICY. JAI -0110 44 . UP. 16/11.4LI NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION April 1972 EP-95 kr) ON THE MOON WITH APOLLO 16 A Guidebook to the Descartes Region by Gene Simmons A * 40. 7 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION April 1972 2 Gene Simmons was Chief Scientist of the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston for two years and isnow Professor of Geophysics at the Mas- sachusetts Institute of Technology. -

Apollo 17 Index

Preparation, Scanning, Editing, and Conversion to Adobe Portable Document Format (PDF) by: Ronald A. Wells University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 May 2000 A P O L L O 1 7 I N D E X 7 0 m m, 3 5 m m, A N D 1 6 m m P H O T O G R A P H S M a p p i n g S c i e n c e s B r a n c h N a t i o n a l A e r o n a u t i c s a n d S p a c e A d m i n i s t r a t i o n J o h n s o n S p a c e C e n t e r H o u s t o n, T e x a s APPROVED: Michael C . McEwen Lunar Screening and Indexing Group May 1974 PREFACE Indexing of Apollo 17 photographs was performed at the Defense Mapping Agency Aerospace Center under the direction of Charles Miller, NASA Program Manager, Aerospace Charting Branch. Editing was performed by Lockheed Electronics Company, Houston Aerospace Division, Image Analysis and Cartography Section, under the direction of F. W. Solomon, Chief. iii APOLLO 17 INDEX 70 mm, 35 mm, AND 16 mm PHOTOGRAPHS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 SOURCES OF INFORMATION .......................................................................................... 13 INDEX OF 16 mm FILM STRIPS ........................................................................................ 15 INDEX OF 70 mm AND 35 mm PHOTOGRAPHS Listed by NASA Photograph Number Magazine J, AS17–133–20193 to 20375......................................... -

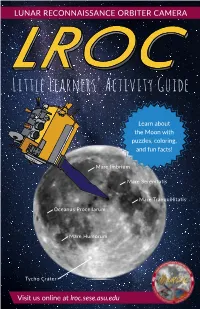

Little Learners' Activity Guide

LUNAR RECONNAISSANCE ORBITER CAMERA Little Learners’ Activity Guide Learn about the Moon with puzzles, coloring, and fun facts! Mare Imbrium Mare Serenitatis Mare Tranquillitatis Oceanus Procellarum Mare Humorum Tycho Crater Visit us online at lroc.sese.asu.edu Online resources Additional information and content, including supplemental learning activities, can be accessed at the following online locations: 1. Little Learners’ Activity Guide: lroc.sese.asu.edu/littlelearners 2. LROC website: lroc.sese.asu.edu 3. Resources for teachers: lroc.sese.asu.edu/teach 4. Learn about the Moon’s history: lroc.sese.asu.edu/learn 5. LROC Lunar Quickmap 3D: quickmap.lroc.asu.edu Copyright 2018, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera i Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Fun Facts for Beginners • The Moon is 363,301 kilometers (225,745 miles) from the Earth. • The surface area of the Moon is almost as large as the continent of Africa. • It takes 27 days for the Moon to orbit around the Earth. • The farside is the side of the Moon we cannot see from Earth. • South Pole Aitken is the largest impact basin on the lunar farside. • Impact basins are formed as the result of impacts from asteroids or comets and are larger than craters. • Regolith is a layer of loose dust, dirt, soil, and broken rock deposits that cover solid rock. • The two main types of rock that make up the Moon’s crust are anorthosite and basalt. • A person weighing 120 lbs on Earth weighs 20 lbs on the Moon because gravity on the Moon is 1/6 as strong as on Earth.