What Is a Hunter-Gatherer? Variation in the Archaeological Record of Eastern and Southern Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explanatory Index of Proper Names Other Than Authors Cited

Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy / Revue Africaine de Philosophie , 24 (2010), 1-2D 1-398 E:planatory inde: of proper names other than authors cited 0xhaustive listing of all proper names other than those of authors cited. 6or names mar2ed with UU also see Inde7 of Authors Cited . Some entries have underlying con- cepts explained under V.v. ( Vuod videre , Esee there=)8 for many other entries this index sei:es the opportunity of explaining details that could not be accommodated in the main text. 1hen a boo2 title is listed, it appears in italic , followed by the author=s name (if any) between parentheses. Inly capitalised text has been processed 9 thus e.g. ECatalyst= is listed but not the many occurrences of Ecatalyst=, Ecatalytic=, etc. Due to last-minute text additions a few page references may be off by 1. identity, 53 227n, 291n8 ,ssyrian ,baris, ,ncient Gree2 Achsenzeit , see ,xial ,ge traces in 9 , 1298 ,rab shaman, 112, 114, 114n ,cragas, 1098 cf. ,grigen- influence on sub- ,b2ha:oids, linguistico- tum Saharan 9, 758 9 and ethnic cluster in the ,dam, Biblical figure, 135 ,ncient Near 0ast, 73, ,ncient 3editerranean, ,donai, .ord, 1608 cf. 1298 9 and North ,mer- 233 ,idoneus ica, 9, 118, 265, 2748 9 ,boriginal ,ustralian, 91, ,egean, Sea and region, and 0urope, 808 and 0ast 1928 cf. Dur2heimUU 115, 141, 151, 175, 294, ,sia, 9 and ,sia, 35, 90, ,braham, Biblical figure, 273n8 9 -,natolian, 226 275, 280, 186n8 1est 162 ,ether, 103-104, 117-118, ,frica, 74, 268, 2818 ,bri du 6acteur, 5pper 130, 137-139, 152, 180- Central ,frica, espe- Palaeolithic site, 189 181, 154n, 165n, 184n8 cially South 9 , 5, 8, 17- ,byss, ,bysmal, 122, ,ether and Day, chil- 18, 31, 43, 62, 64, 70, 164, 236, 101n8 cf. -

Tsodilo Hill, Botswana

Alec Campbell and Lawrence Robbins Tsodilo Hill, Botswana The Tsodilo Hills in northwestern Botswana were listed as World Heritage in 2001 on account of their prolific rock art, some 4 000 images, 100 000-year occupation by humans, prehistoric specularite mining, early occupation by pastoral Khwe and Black farmers, spiritual importance to their modern residents and unique attributes in a land of endless sand dunes. Tsodilo Hills are situated in a remote region of nium AD farmer villages. Local residents of the the Kalahari Desert in northwest Botswana. Hills, Ju/’hoansi (Bushmen) and Hambukushu The Hills form a 15km-long chain of four (Bantu-speaking farmers) still recognise the quartzite-schist outcrops rising, the highest Hills as sacred. to 400m, above Aeolian sand dunes. The Hills contain evidence of some 100 000 years of Background intermittent human occupations, over 4 000 Tsodilo’s rock paintings, first noted by the rock paintings, groups of cupules, at least 20 outside world in 1898, received legal protec- prehistoric mines, and remains of First Millen- tion only in the late 1930s. The law protecting Fig. 1. Western cliffs that glow a copper colour in evening light giving the Hills their N/ae name, ‘Copper Bracelet of the Evening’. 34 the paintings also prohibited illegal excava- Archaeology tions and damage to, or theft of ‘Bushman Excavations have told us something about (archaeological) relics’, but failed to protect past human occupations of the Hills. White the Hills and their plants or wildlife. Paintings Shelter, excavated to a depth of Research, mainly undertaken by Botswana’s seven metres, has disclosed human-made ar- National Museum, commenced in 1978 with tefacts dating back almost to 100 000 years. -

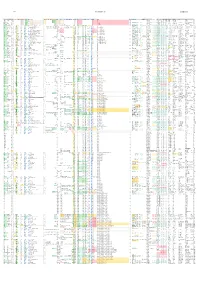

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

A Heritage and Cultural Tourism Destination

MAKING GABORONE A STOP AND NOT A STOP-OVER: A HERITAGE AND CULTURAL TOURISM DESTINATION by Jane Thato Dewah (Student No: 12339556) A Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HERITAGE AND CULTURAL STUDIES) (TOURISM) In the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria SUPERVISOR: Prof. K.L Harris December 2014 DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not been submitted previously at any other university for a degree. ............................................... Signature Jane Thato Dewah ................................................ Date ii Abstract The main objective of the study was to identify cultural heritage sites in and around Gaborone which could serve as tourist attractions. Gaborone, the capital city of Botswana, has been neglected in terms of tourism, although it has all the facilities needed to cater for this market. Very little information with regards to tourist attractions around Gaborone is available and therefore this study set out to identify relevant sites and discussed their history, relevance and potential for tourism. It also considers ways in which these sites can be developed in order to attract tourists. Due to its exclusive concentration on wildlife and the wilderness, tourism in Botswana tends to benefit only a few. Moreover, it is mainly concentrated in the north western region of the country, leaving out other parts of the country in terms of the tourism industry. To achieve the main objective of the study, which is to identify sites around the capital city Gaborone and to evaluate if indeed the sites have got the potential to become tourist attractions, three models have been used. -

1 Creating a Better Tourist Experience Through The

ISSUE SIX (2017) Creating a better tourist experience through the presentation and interpretation of World Heritage Values in Botswana Tshepang Rose Tlatlane Introduction Communities across the world have gradually transformed tourism from time at the beach, sun and sand (Adams 2006), to spending time at World Heritage sites learning about their preservation. There is strong evidence from research that local guides and traditional leaders play a fundamental role in educating tourists about local cultures. Mass tourism regrettably causes a lot of environmental challenges; Ghulam Rabbany et al (2013) confirm the direct impacts of tourism on the environment which include things such as alteration of natural habits, noise and air pollution, loss of biological diversity, and littering. In Botswana, littering is considered one of the eye sore at the famous Okavango Delta. Littering has significantly impacted tourism development in the Okavango Delta and the entire industry in Botswana (Mbaiwa 2004). As tourism is heavily dependent on the quality of the environment, it is crucial for all stakeholders to protect the environment for it to continue being a sustainable economic resource. One of the major issues is the role of mass tourism in environmental protection and sustainable tourism. Is destruction in mass tourism avoidable? A possible answer is Smith’s (1956) market segmentation strategy of grouping tourists in a way that is of most manageable value. Market segmentation results in niche tourism as tourists are divided into smaller groups, according to their needs, behaviours and expectations (Adams 2006). Heritage tourism has observed a significant growth in recognition as a niche in Botswana. -

Excavations at Mlambalasi Rockshelter: a Terminal Pleistocene to Recent Iron Age Record in Southern Tanzania

Afr Archaeol Rev DOI 10.1007/s10437-017-9253-3 RESEARCH REPORT Excavations at Mlambalasi Rockshelter: a Terminal Pleistocene to Recent Iron Age Record in Southern Tanzania K. M. Biittner & E. A. Sawchuk & J. M. Miller & J. J. Werner & P. M. Bushozi & P. R. Willoughby # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The Mlambalasi rockshelter in the Iringa Re- millennia as diverse human groups were repeatedly gion of southern Tanzania has rich artifactual deposits attracted to this fixed feature on the landscape. spanning the Later Stone Age (LSA), Iron Age, and historic periods. Middle Stone Age (MSA) artifacts are Résumé L'abri sous roche Mlambalasi dans la région also present on the slope in front of the rockshelter. d'Iringa au sud de la Tanzanie est riche en artéfacts du Extensive, systematic excavations in 2006 and 2010 Paléolithique supérieur jusqu'à l'âge du fer et la by members of the Iringa Region Archaeological Project période historique. Des artéfacts du Paléolithique (IRAP) illustrate a complex picture of repeated occupa- moyen sont présents sur le versant en face de l'abri. tions and reuse of the rockshelter during an important Des fouilles extensives et systématiques réalisées par time in human history. Direct dates on Achatina shell l’équipe d’Iringa Region Archaeological Project and ostrich eggshell (OES) beads suggest that the earli- (IRAP) révèlent une image complexe de l’utilisation est occupation levels excavated at Mlambalasi, which et de la réutilisation de l'abri sous roche pendant un are associated with human burials, are terminal Pleisto- moment important dans l'histoire de l'humanité. -

The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe

Open Archaeology 2018; 4: 185–205 Original Study Sibylle Wolf*, Rimtautas Dapschauskas, Elizabeth Velliky, Harald Floss, Andrew W. Kandel, Nicholas J. Conard The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2018-0012 Received June 8, 2017; accepted December 13, 2017 Abstract: While the earliest evidence for ochre use is very sparse, the habitual use of ochre by hominins appeared about 140,000 years ago and accompanied them ever since. Here, we present an overview of archaeological sites in southwestern Germany, which yielded remains of ochre. We focus on the artifacts belonging exclusively to anatomically modern humans who were the inhabitants of the cave sites in the Swabian Jura during the Upper Paleolithic. The painted limestones from the Magdalenian layers of Hohle Fels Cave are a particular focus. We present these artifacts in detail and argue that they represent the beginning of a tradition of painting in Central Europe. Keywords: ochre use, Middle Stone Age, Swabian Jura, Upper Paleolithic, Magdalenian painting 1 The Earliest Use of Ochre in the Homo Lineage Modern humans have three types of cone cells in the retina of the eye. These cells are a requirement for trichromatic vision and hence, a requirement for the perception of the color red. The capacity for trichromatic vision dates back about 35 million years, within our shared evolutionary lineage in the Catarrhini subdivision of the higher primates (Jacobs, 2013, 2015). Trichromatic vision may have evolved as a result of the benefits for recognizing ripe yellow, orange, and red fruits in front of a background of green foliage (Regan et al., Article note: This article is a part of Topical Issue on From Line to Colour: Social Context and Visual Communication of Prehistoric Art edited by Liliana Janik and Simon Kaner. -

Cultural Transmission and Lithic Technology in Middle Stone Age Eastern Africa

Cultural Transmission and Lithic Technology in Middle Stone Age Eastern Africa by Kathryn L. Ranhorn B.A. in Anthropology, May 2010, University of Florida A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2017 Dissertation directed by Alison S. Brooks Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs David R. Braun Associate Professor of Anthropology The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Kathryn L. Ranhorn has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of May 9th, 2017. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Cultural Transmission and Lithic Technology in Middle Stone Age Eastern Africa Kathryn L. Ranhorn Dissertation Research Committee: Alison S. Brooks, Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs, Dissertation Co-Director David R. Braun, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Dissertation Co-Director Francys Subiaul, Associate Professor of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, Committee Member Christian A. Tryon, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Harvard University Committee Member ii © Copyright 2017 by Kathryn L. Ranhorn All rights reserved. iii Dedication To my mother, who taught me that evolution requires sometimes copying old ideas, and often creating new ones. Na pia kwa marafiki wangu wa Tanzania na Kenya, hii ndo story zenu. Bado tunapanda. -- “It sometimes appears that all of us treat stone artifacts as infinitely complex repositories of paleocultural information and assume that it is only the imperfections of our present analytical systems that prevent us from decoding them. -

Concerning a Cupule Sequence on the Edge of the Kalahari Desert in South Africa

Rock Art Research 2015 - Volume 32, Number 2, pp. 163-177. P. B. BEAUMONT and R. G. BEDNARIK 163 KEYWORDS: Cupule – Age estimate – Palaeoenvironment – Tswalu Kalahari Reserve – South Africa CONCERNING A CUPULE SEQUENCE ON THE EDGE OF THE KALAHARI DESERT IN SOUTH AFRICA Peter B. Beaumont and Robert G. Bednarik Abstract. The Tswalu Reserve in the southern Kalahari is an arid place, the present occupation of which is only made possible by means of boreholes that tap patches of fossil water, while semi-permanent surface sources of ~65 m2 extent are confined to three localities within an investigated area of over 1000 km2. Lithic evidence indicates that this vicinity was abandoned by humans during even drier Ice Age intervals, when rainfall fell at times to ~40% of present values, thereby providing a way to refer petroglyphs there to interglacials of known age and intensity in terms of regional and global paleaoclimatic data. By such means, together with microerosion measurements, it then becomes possible to identify three regional cupule production intervals: the earliest with cupules only at ~410–400 ka bp, the next with cupules and outline circles at ~130–115 ka ago, and the most recent, with cupules, geometric motifs and iconic images, at ~8–2 ka bp. Introduction then, but the later dating of various regional sites (Miller Cupules are manmade, roughly semi-hemispherical 1971; Sampson 1974) placed the artefact level between depressions, not normally more than ~8 cm in diame- ~25 and 13 cal ka ago (Weninger and Jöris 2008), and it ter, that were produced on hard rock surfaces by is consequently considered probable that the Chifubwa hammerstone percussion (Kumar and Krishna 2014), petroglyphs were made at some time within that reportedly supplemented or replaced on softer stones interval (Clark 1958). -

Bantu Expansion Shows That Habitat Alters the Route and Pace of Human Dispersals

Bantu expansion shows that habitat alters the route and pace of human dispersals Rebecca Grollemunda,1, Simon Branforda, Koen Bostoenb, Andrew Meadea, Chris Vendittia, and Mark Pagela,c,1 aEvolutionary Biology Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Reading RG6 6BX, England; bKongoKing Research Group, Department of Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; and cThe Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM 87501 Edited by Peter S. Bellwood, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 10, 2015 (receivedfor review February 25, 2015) Unlike most other biological species, humans can use cultural inno- at ∼2,500 B.P. affected amongst others the western part of the vations to occupy a range of environments, raising the intriguing Congo Basin, creating patches of more or less open forests and question of whether human migrations move relatively indepen- wooded or grassland savannahs (14, 15). These areas eventually dently of habitat or show preferences for familiar ones. The Bantu merged into a corridor known as the “Sangha River Interval” that expansion that swept out of West Central Africa beginning ∼5,000 y repeatedly facilitated the north–southspreadofcertaintypical ago is one of the most influential cultural events of its kind, even- savannah plant and animal species (17, 20–22). tually spreading over a vast geographical area a new way of life in The Sangha River Interval may also have been a crucial pas- which farming played an increasingly important role. We use a new sageway for the initial north–south migration of Bantu speech dated phylogeny of ∼400 Bantu languages to show that migrating communities across the Equator. -

The Role of Experimental Knapping in Empirically Testing Key Themes in the Evolution of Lithic Technology: Reduction Intensity, Efficiency and Behavioural Complexity

The role of experimental knapping in empirically testing key themes in the evolution of lithic technology: reduction intensity, efficiency and behavioural complexity Antoine Muller BA (archaeology) BA Honours (archaeology) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2017 School of Social Science Abstract Experimental knapping has complimented and stimulated lithic analyses for over a century. Throughout this period, the discipline has witnessed an increase in the scientific rigour and theoretical grounding with which these studies are conducted. This thesis charts these key trends and in doing so establishes a best-practice model of experimental knapping, the veracity of which is in turn tested using four new lithic experiments. These case-studies employ experimental knapping to advance our understanding of flake platform measurement, reduction intensity, technological efficiency, and behavioural complexity. The first case-study, Chapter 3, offers a more accurate and precise calliper-based method of flake platform measurement that relies on simple geometric approximations of platform shape rather than the inflexible and unreliable existing method of multiplying platform width by thickness. In Chapter 4, a new reduction intensity metric for backed blades, a hitherto overlooked tool-type, is developed and tested on the backed blades from an early Neolithic site in Turkey. This new metric allows a reconstruction of the raw material consumption patterns at the site, finding that the backed blades likely contributed to conserving the inhabitants’ scarce lithic raw material. Meanwhile, Chapter 5 outlines the results of a comparison of the raw material efficiency of eight different lithic technologies, finding that lithic technological efficiency was a generally ascending trend over the last 3.3 million years and that the main transition in efficiency occurred between the Lower to Middle Palaeolithic. -

Figures Kristen Et Al Proof

Originally published as: Kristen, I., Fuhrmann, A., Thorpe, J., Röhl, U., Wilkes, H., Oberhänsli, H. (2007): Hydrological changes in southern Africa over the last 200 Ka as recorded in lake sediments from the Tswaing impact crater. - South African Journal of Geology, 110, 2-3, 311-326, DOI: 10.2113/gssajg.110.2-3.311. Hydrological changes in southern Africa over the last 200 kyr as recorded in lake sediments from the Tswaing impact crater I. Kristen GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, D-14473 Potsdam, Germany, [email protected] A. Fuhrmann GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, D-14473 Potsdam, Germany Present address: Saudi Aramco, Dhahran 31311, Saudi Arabia, [email protected] J. Thorpe formerly at Department of Geography, University College London, 26 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AP, Great Britain, [email protected] U. Röhl Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (MARUM), Universität Bremen, Leobener Strasse, 28359 Bremen, Germany, [email protected] H. Wilkes GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, D-14473 Potsdam, Germany, [email protected] and H. Oberhänsli GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, D-14473 Potsdam, Germany, [email protected] Short working title: Hydrological changes recorded in sediments from Lake Tswaing (South Africa) Abstract Sediments from Lake Tswaing (25°24’30’’ S, 28°04’59’’ E) document hydrological changes in southern Africa over the last 200 kyr. Using high-resolution XRF- scanning, basic geochemistry (TIC, TOC, TN), organic petrology and Rock-Eval pyrolysis, we identify intervals of decreased carbonate precipitation, increased detrital input, decreased salinity and decreased autochthonous (algal and bacterial) organic matter content that represent periods of less stable water column stratification and increased rainfall.