Joint Theatre Entry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Fighters Problem, Recent Trends and Case Studies: Selected Essays

Program on National Security at the FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Al-Qaeda al-Shabaab AQIM AQAP Central The Foreign Fighters Problem, Recent Trends and Case Studies: Selected Essays Edited by Michael P. Noonan Managing Director, Program on National Security April 2011 Copyright Foreign Policy Research Institute (www.fpri.org). If you would like to be added to our mailing list, send an email to [email protected], including your name, address, and any affiliation. For further information or to inquire about membership in FPRI, please contact Alan Luxenberg, [email protected] or (215) 732-3774 x105. FPRI 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 About FPRI Founded in 1955, the Foreign Policy Research Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. We add perspective to events by fitting them into the larger historical and cultural context of international politics. About FPRI’s Program on National Security The end of the Cold War ushered in neither a period of peace nor prolonged rest for the United States military and other elements of the national security community. The 1990s saw the U.S. engaged in Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and numerous other locations. The first decade of the 21st century likewise has witnessed the reemergence of a state of war with the attacks on 9/11 and military responses (in both combat and non-combat roles) globally. While the United States remains engaged against foes such as al-Qa`ida and its affiliated movements, other threats, challengers, and opportunities remain on the horizon. -

Rights Watch

British Irish RIGHTS WATCH SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE CONCERNING THE UNITED KINGDOM’S COMPLIANCE WITH THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS SEPTEMBER 2007 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 British Irish RIGHTS WATCH is an independent non-governmental organisation that monitors the human rights dimension of the conflict and the peace process in Northern Ireland. Our services are available free of charge to anyone whose human rights have been affected by the conflict, regardless of religious, political or community affiliations, and we take no position on the eventual constitutional outcome of the peace process. 1.2 This submission to the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations concerns the United Kingdom’s observance of the provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). All our comments stem directly from our work and experience. In the interests of brevity, we have kept details to a minimum, but if any member of the Committee would like further information about anything in this submission, we would be happy to supply it. Throughout the submission we respectfully suggest questions that the Committee may wish to pose to the United Kingdom (UK) during its examination of the UK’s sixth periodic report. 2. THE UNITED KINGDOM AND HUMAN RIGHTS 2.1 In its 2001 examination of the United Kingdom’s observance of the provisions of the ICCPR, the Human Rights Committee recommended that the United Kingdom incorporate all the provisions of the ICCPR into domestic law1. However, the UK has yet to comply with this recommendation. Suggested question: · What plans does the UK have for incorporating all provisions of the ICCPR into domestic law and what is the timetable? 2.2 The Human Rights Committee’s last examination of the UK’s observance of the provisions of the ICCPR further recommended that the UK should consider, as a priority, accession to the first Optional Protocol2. -

30 Books on Terrorism & Counter- Terrorism

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 5 Counterterrorism Bookshelf: 30 Books on Terrorism & Counter- Terrorism-Related Subjects Reviewed by Joshua Sinai The books reviewed in this column are arranged according to the following topics: “Terrorism – General,” “Suicide Terrorism,” “Boko Haram,” “Islamic State,” “Northern Ireland,” and “Pakistan and Taliban.” Terrorism – General Christopher Deliso, Migration, Terrorism, and the Future of a Divided Europe: A Continent Transformed (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Security International, an Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2017), 284 pp., US $ 75.00 [Hardcover], ISBN: 978-1-4408-5524-5. This is a well-informed account of the impact of Europe’s refugee crisis that was generated by the post-Arab Spring conflicts’ population displacements affecting the continent’s changing political climate, economic situation, and levels of crime and terrorism. In terms of terrorism, the author points out that several significant terrorist attacks involved operatives who had entered European countries illegally, such as some members of the cells that had carried out the attacks in Paris (November 2015) and Brussels (March 2016). With regard to future terrorism trends, the author cites Phillip Ingram, a former British intelligence officer, who observed that “Conservative estimates suggest thousands of extremists have managed to slip in through the refugee crisis. And a significant number of them have experience in fighting and in planning not only simple operations, but the kind of complex ones seen in Paris and Brussels” (p. 87). The migration crisis is also affecting Europe’s politics, the author concludes, with “the fault lines of increasingly polarized left- and right-wing partisan ideologies… resulting in earthquakes of various sizes, in Europe and around the world” (p. -

The Evolution of British Intelligence Assessment, 1940-41

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 The evolution of British intelligence assessment, 1940-41 Tang, Godfrey K. Tang, G. K. (1999). The evolution of British intelligence assessment, 1940-41 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/18755 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25336 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Evolution of British Intelligence Assessment, 1940-41 by Godfiey K. Tang A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FLTLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 1999 O Godfiey K Tang 1999 National Library Biblioth4que nationale #*lof Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant Pla National Library of Canada to Blbliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distciiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/f&n, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format Bectronique. -

2020 Fellowship Profile

2020 Fellowship Profile BY THE NUMBERS Europe DENMARK SLOVAK REPUBLIC New Returning 3 Countries 8 Countries Lieutenant Colonel Lene Lillelund Colonel Ivana Gutzelnig, MD North America Battalion Commander Director Oceania Logistics Regiment Military Centre of Aviation Medicine Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic CANADA Danish Army AUSTRALIA Higher Colonel Geneviève Lehoux SWITZERLAND Languages FRANCE Colonel Rebecca Talbot Education Director 9 Spoken 29 Chief of Staff Degrees Military Careers Administration Canadian Armed Forces Colonel Valérie Morcel Major General Germaine Seewer Supply Chain Branch Head Commandant, Armed Forces College Australian Defence Force 54th Signals Regiment Deputy Chief, Training and Education UNITED STATES French Army Command Swiss Armed Forces NEW ZEALAND Years of Colonel Katharine Barber GERMANY Deployments Combined Wing Commander for the Air Force UNITED KINGDOM 31 285 Group Captain Carol Abraham Service Technical Applications Center Colonel Dr. Stephanie Krause Patrick Air Force Base Florida Chief Commander Colonel Melissa Emmett Defence Strategy Management United States Air Force Medical Regiment No 1 Corps Colonel New Zealand Defence Force German Armed Forces Intelligence Corps INTERESTS Captain Rebecca Ore British Army Commander Sector Los Angeles-Long Beach o Leadership in Conflict Zones United States Coast Guard THE NETHERLANDS o Impacts of Climate and Food Insecurity on Stability Colonel Rejanne Eimers-van Nes Commander o Space Policy Personnel Logistics o Effective and Ethical Uses of AI Royal -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch

WAR CRIMES PROSECUTION EDITOR IN CHIEF Jessica Feil FREDERICK K. COX WATCH INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER MANAGING EDITORS Sana Ahmed Michael P. Scharf and Volume 7 - Issue 12 Sarah Nasta Brianne M. Draffin, Advisors September 10, 2012 SENIOR TECHNICAL EDITOR Steven Paille War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT Central African Republic & Uganda BembaTrial.org: Judges Reject Prosecution Bid to Exclude a Defense Expert Witness BembaTrial.org: Expert Says Bemba Troops Were a "Legitimate" Force in the CAR Conflict BembaTrial.org: Geopolitical Expert Says Bemba Troops Represented Congo in CAR Conflict BembaTrial.org: Prosecutors Challenge Report of Geopolitical Expert BembaTrial.org: Bemba's Top Commander 'Took Orders from CAR Army Chief' Democratic Republic of the Congo LubangaTrial.org: Q&A with Paolina Massidda, Principal Counsel of the Office of the Public Counsel for Victims at ICC Kenya The Star: ICC Prosecutor Updates Charges Against Kenyan PEV Suspects The Star: -

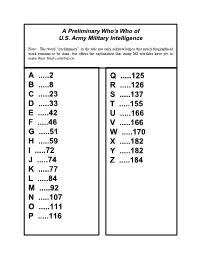

A Preliminary Who's Who of US Army Military Intelligence

A Preliminary Who’s Who of U.S. Army Military Intelligence Note: The word preliminary in the title not only acknowledges that much biographical work remains to be done, but offers the explanation that many MI worthies have yet to make their final contribution. A .....2 Q .....125 B .....8 R .....126 C .....23 S .....137 D .....33 T .....155 E .....42 U .....166 F .....46 V .....166 G .....51 W .....170 H .....59 X .....182 I .....72 Y .....182 J .....74 Z .....184 K .....77 L .....84 M .....92 N .....107 O .....111 P .....116 A Aaron, Harold R. Lt. Gen. [Member of MI Hall of Fame. Aaron Plaza dedicated at Fort Huachuca on 2 July 1992.] U.S. Military Academy Class of June 1943. Distinguished service in special operations and intelligence assignments. Commander, 5th Special Forces Group, Republic of Vietnam; Deputy Chief of Staff, Intelligence, U.S. Army, Europe. Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence, Department of the Army; Deputy Director, Defense Intelligence Agency. Extract from Register of Graduates, U.S. Military Academy, 1980: Born in Indiana, 21 June 1921; Infantry; Company Commander, 259 Infantry, Theater Army Europe, 1944 to 1945 (two Bronze Star Medals-Combat Infantry Badge-Commendation Ribbon-Purple Heart); Command and General Staff College, 1953; MA Gtwn U, 1960; Office of Assistant Secretary of Defense, 1961 to 1963; National War College, 1964; PhD Georgetown Univ, 1964; Aide-de-Camp to CG, 8th Army, 1964 to 1965; Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1965 to 1967; (Legion of Merit); Commander, 1st Special Forces Group, 1967 -

Unmasking Gchq: the Abc Trial 341

UNMASKING GCHQ: THE ABC TRIAL 341 18 too large for any human to read. Moreover, the vast complexes of domes and satellite dishes that now accompanied the suppos- Unmasking GCHQ: The ABC Trial edly super-secret intelligence activities of NSAand GCHQmeant that they were more and more visible. Sooner rather than later, an enterprising investigative journalist was bound to point to these surreal installations and shout the dreaded words 'Signals We've been to MI5, MI6, Scotland Yard, Parliament and many intelligence.' It is amazing that in the mid-1970s GCHQ was more. Now we're going where much of the dirty work goes on - still managing to pass itself off as a glorified communications CHELTENHAM! relay station, hiding its real activities from public view. ABC trial campaign newsletter, 27 May 19781 Anonymity would not last much longer. What we now recognise as the first glimmerings of a global telecommunications revolution seemed 10 be in the interests of the world's major sigint agencies. A fascinating example of this During the late 1960s and early 1970s, signals intelligence was was an operation carried out jointly by the British and Americans changing fast. The big players were discovering a whole new in 1969. NSA was gathering a great deal of intelligence from world of super-secret interception which provided a different telephone callsbetween Fidel Castro's Cuba and the many Cuban sort of signals intelligence. This new source was telephone calls. exiles living in Florida. Using sigint ships, it was also possible As we have already seen, tapping telephones was hardly new, 10 intercept some calls from Havana to other parts of Cuba. -

Logistics for Joint Operations

Joint Doctrine Publication 4-00 Logistics for Joint Operations Joint Doctrine Publication 4-00 (JDP 4-00) (4th Edition), dated July 2015, is promulgated as directed by the Chiefs of Staff Director Concepts and Doctrine Conditions of release 1. This information is Crown copyright. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) exclusively owns the intellectual property rights for this publication. You are not to forward, reprint, copy, distribute, reproduce, store in a retrieval system, or transmit its information outside the MOD without VCDS’ permission. 2. This information may be subject to privately owned rights. JDP 4-00 (4th Edition) i Authorisation The Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC) is responsible for publishing strategic trends, joint concepts and doctrine. If you wish to quote our publications as reference material in other work, you should confirm with our editors whether the particular publication and amendment state remains authoritative. We welcome your comments on factual accuracy or amendment proposals. Please send them to: The Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre Ministry of Defence Shrivenham SWINDON, Wiltshire, SN6 8RF Telephone: 01793 314216/7 Facsimile number: 01793 314232 Military network: 96161 4216/4217 Military Network: 96161 4232 E-mail: [email protected] All images, or otherwise stated are: © Crown copyright/MOD 2015. Distribution Distributing Joint Doctrine Publication (JDP) 4-00, Logistics for Joint Operations (4th Edition) is managed by the Forms and Publications Section, LCSLS Headquarters and Operations Centre, C16 Site, Ploughley Road, Arncott, Bicester, OX25 1LP. All of our other publications, including a regularly updated DCDC Publications Disk, can also be demanded from the LCSLS Operations Centre. -

JFQ 47 Chinese Sailors Man the Rails As Download As Computer Wallpaper at Ndupress.Ndu.Edu Qingdoa Enters Pearl Harbor

4 pi J O I N T F O R C E Q uarterly Issue 47, 4th Quarter 2007 New Books from NDU Press Published for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff by National Defense University JFQ Congress At War: coming next in... The Politics of Conflict Since 1789 by Charles A. Stevenson Homeland Defense Reviews the historical record of the U.S. Congress in authorizing, funding, overseeing, and terminating major military operations. Refuting arguments that Congress cannot and should not set limits or conditions on the use of the U.S. Armed Forces, this book catalogs the many times when previous Congresses have enacted restrictions—often with the acceptance and compliance of wartime Presidents. While Congress has formally declared war only 5 U.S. Northern Command times in U.S. history, it has authorized the use of force 15 other times. In recent decades, however, lawmakers have weakened their Constitutional claims by failing on several occasions to enact measures either supporting or opposing military operations ordered by the President. plus Dr. Charles A. Stevenson teaches at the Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins Uni- versity. A former professor at the National War College, he also draws upon his two decades as a Senate staffer Download as computer wallpaper at ndupress.ndu.edu on national security matters to illustrate the political motivations that influence decisions on war and peace Defense Support of Concise, dramatically written, and illustrated with summary tables, this book is a must-read for anyone inter- Civil Authorities ested in America’s wars—past or present. -

Bin Laden and Al Qaeda Thematic Bibliography No

Public Diplomacy Division Room Nb123 B-1110 Brussels Belgium Tel.: +32(0)2 707 4414 / 5033 (A/V) Fax: +32(0)2 707 4249 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.nato.int/library Bin Laden and Al Qaeda Thematic Bibliography no. 5/11 Ben Laden et Al-Qaida Bibliographie thématique no. 5/11 Division de la Diplomatie Publique Bureau Nb123 B-1110 Bruxelles Belgique Tél.: +32(0)2 707 4414 / 5033 (A/V) Fax: +32(0)2 707 4249 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.nato.int/library How to borrow items from the list below : As a member of the NATO HQ staff you can borrow books (Type: M) for one month, journals (Type: ART) and reference works (Type: REF) for one week. Individuals not belonging to NATO staff can borrow books through their local library via the interlibrary loan system. How to obtain the Multimedia Library publications : All Library publications are available both on the NATO Intranet and Internet websites. Comment emprunter les documents cités ci-dessous : En tant que membre du personnel de l'OTAN vous pouvez emprunter les livres (Type: M) pour un mois, les revues (Type: ART) et les ouvrages de référence (Type: REF) pour une semaine. Les personnes n'appartenant pas au personnel de l'OTAN peuvent s'adresser à leur bibliothèque locale et emprunter les livres via le système de prêt interbibliothèques. Comment obtenir les publications de la Bibliothèque multimédia : Toutes les publications de la Bibliothèque sont disponibles sur les sites Intranet et Internet de l’OTAN. -

CI Reader Volume II

TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1Counterintelligence In World War II ................................................................................... 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) .................................................................................................. 3 Storm on the Horizon ....................................................................................................................... 3 Contributing to Victory.................................................................................................................... 4 A New Kind of Conflict ................................................................................................................... 4 A Continuing Need .......................................................................................................................... 5 Colepaugh and Gimpel ............................................................................................................................ 5 The Custodial Detention Program ........................................................................................................ 17 President Roosevelts Directive of December 1941 ............................................................................. 21 German Espionage Ring Captured .......................................................................................................