Northamptonshire Past & Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda, Council, 2021-01-21

COLD HIGHAM PARISH COUNCIL Postal Address: 8 Compton Way, Earls Barton, NN6 0PL Email: [email protected] Website: www.coldhigham-pc.gov.uk All Councillors are summoned to attend the Meeting of Cold Higham Parish Council to be held virtually (joining instructions below) on Thursday 21 January 2021 at 11.00 am. AGENDA 1. Apologies to be accepted. 2. Declarations of Interest. 3. Reports from District and County Councillors. 4. Public Session. 5. Approval and Signature of the minutes of the Ordinary meeting of the 19 November 2020 and Extraordinary Meeting of the 10 December 2020. 6. Matters Arising: a. Precept demand update. 7. Correspondence to note or agree action where needed. 8. Open Spaces: a. Rights of Way – paths and styles. b. Street furniture, telephone boxes and signage update. c. Litter pick. 9. Churchyard: a. Council responsibilities for maintaining the churchyard. b. Review of policies and rules - update. c. Maintenance update and approve action or budget requirements. Cllrs Forster & Hurford to report. d. Cemetery Hedge – request from resident for additional maintenance. 10. Planning Matters. a. Planning consultation/Information. 11. Renew Internet Security Software (McAfee Subscription expires 28 March 2021) – approve renewal and budget. 12. NCC Urban Highway Grass Mowing Grant 2021. Council to decide to apply for grant. 13. Finance & Admin. a. Approve bank reconciliation as of 30 December 2020 – separate paper. b. To receive receipts: i. NatWest Bank Interest: 29 November 2020 £0.17p ii. NCC: Urban Highway Grass Mowing Grant 23 December 2020 £149.72 c. To approve payments: Chq Payee Purpose VAT Amount Powers 1030 G Greaves Clerks Salary January 21 £239.98 Local Government (Financial Provisions) Act 1963 s5 1031 HMRC Clerks PAYE January £59.80 Local Government 2021 (Financial Provisions) Act 1963 s5 1032 E-ON Streetlight works £191.98 £1,151.88 Highways 1980 Act. -

Gayton News March 2016

GAYTON NEWS MARCH 2016 Issue No 131 Wishing Queen Elizabeth II a very Happy 90th Birthday on 21 April 2016 Thursday 12 - Sunday 15 May: The Queen and Members of the Royal Family will attend a pageant celebrating The Queen’s life to be held at Home Park in Windsor Castle. Friday 10th June: The Queen and The Duke of Edinburgh will attend a National Service of Thanksgiving at St. Paul's Cathedral. Saturday 11th June: Her Majesty accompanied by Members of the Royal Family will attend at The Queen’s Birthday Parade on Horse Guards Parade. Sunday 12th June: The Queen will attend the Patron's Lunch, a celebration of Her Majesty's patronage of over 600 organisations in the UK and around the Commonwealth since 1952. *************************************************************************** As we all very well know, the rain and storms have been beyond belief this winter, especially for those in the north. Just one of the schools badly affected is Burnley Road Academy in Calderdale, which suffered severe flood damage. In excess of 16,000 homes across Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cumbria and parts of Scotland were affected and the cost of the damage is over £1billion. A teacher from Upton Meadows Primary School had the idea of sending unwanted children’s books to the schools affected. She got in touch with the Northamptonshire Emergency Response Corps (NERC), a Community Organisation and Charity who brings together various agencies involved in emergency response in the County, who launched an appeal which was then supported by Northampton County Council to help schools replace the hundreds of books they lost in the floods. -

Collingtree News

A NEWSLETTER PRODUCED FOR COLLINGTREE PAROCHIAL CHURCH COUNCIL ON BEHALF OF COMMUNITY GROUPS IN COLLINGTREE PARISH Collingtree news August 2014 Visit the only website dedicated to Collingtree village & parish www.justcollingtree.co.uk The Master Plan for the proposed Distribu- tion Centre showing the part dual carriage- way widening of the A508 to Roade Major Development Proposal at Junction 15 - The hard questions . Property developer Roxhill has joined with Courteenhall are having to import more and more of our food ? Estates to promote a 2m sq ft National Distribution Centre How does this site fit with the Strategic Plan for the for kitchen manufacturer Howden’s, on farmland adjoin- area which currently identifies more sustainable ing Junction 15. sites with access to Junction 16 ? The development will be double the size of Howden’s ex- isting Distribution Centre at Brackmills. In 2013 its fleet of With the M1 corridor already exceeding Air Quality 90 HGV’s delivered 90,000 loads to its 559 depots every limits, how will emissions from the additional vehi- week. cles using the site be controlled ? The consultation leaflet delivered to households in the The proposal offers to provide ‘significant improve- area failed to mention Collingtree on its location map. An ments to the existing problems at Junction 15. Can exhibition of site plans was held at the Hilton Hotel on this really be achieved by simply installing more traf- 16th July and details from this are on website fic lights and widening slip roads ? www.northampton-gateway.co.uk/howdens. As with all planning proposals there will be many pros and Although the proposed site mainly affects Northampton, cons but most of the hard questions have yet to be an- the planning application, expected later in the year, will be swered: decided by South Northamptonshire District Council in Is it wise to build on yet more farmland when we Towcester. -

Northampton Diverse Communities Equalities Forum Agenda

Northampton Diverse Communities Equalities Forum on Wednesday, 6 June 2012 at 6:30 pm until not later than Time Not Specified in The Holding Room, The Guildhall, St. Giles Square, Northampton, NN1 1DE. Agenda 1. Welcomes and Introductions 2. Apologies 3. Minutes and matters arising 4. Northampton Carnival Archive Project 5. Community Information Exchange 6. Indian Hindu Welfare Organisation and Temple project update 7. Any Other Buisness 8. Items for Discussion at the Next Meeting 9. Date Of Next Meeting The date of the next meeting 18 th July 2012 at 6.30pm. Map and directions at: www.northampton.gov.uk/guildhall For more information about this meeting please contact: Lindsey Ambrose, Community Engagement and Equalities Officer: [email protected] Tel/Text: 0779 53 33 687 (including evenings and weekends) Tel: 01604 837566 More information about the Forum generally is at: www.northampton.gov.uk/forums Facebook page: www.facebook.com/NorthamptonPensionersForum Please note that this Forum is supported and funded by Northampton Borough Council. The Forum may work in partnership and collaboration with other community groups, councils and local services from time to time. The views expressed and decisions taken by the Forum are not necessarily those of Northampton Borough Council. Agenda Item 3 Northampton Borough Council Northampton Diverse Communities Equalities Forum Tuesday, 17 April 2012 Officers at the meeting 1. WELCOMES AND INTRODU CTIONS John Rawlings in the Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting. He explained the forum is open to anyone with an interest in diversity and communities and this normally informs the direction of discussion. -

Memories of Pitsford a 100 Years Ago

49 MEMORIES OF PITSFORD A HUNDRED YEARS AGO T. G. TUCKER Introduction by the late Joan Wake* All my life I had heard of the clever Pitsford boy, Tom Tucker-whose name was a legend in the Wake family. I knew he had emigrated to Australia a.s a young man and I had therefore never expected to see him in the flesh-when all of a sudden in the middle of my third war-he turned up! This was in 1941. He got into touch with my aunt, Miss Lucy Wake, who had known him as a boy, and through her I invited him to come and stay with me for a few days in my little house at Cosgrove. He was then a good-looking, white haired old gentleman, of marked refinement, and of course highly cultivated, and over eighty years of age. He was very communicative, and I much enjoyed his visit. Tom's father was coachman, first to my great-great-aunt Louisa, Lady Sitwell, at Hunter- combe near Maidenhead in Berkshire, and then to her sister, my great-grandmother, Charlotte, Lady Wake, at Pitsford. Tom described to me the two days' journey in the furniture van from one place to the other-stopping the night at Newport Pagnell, and the struggle of the horses up Boughton hill, slippery with ice, as they neared the end of their journey. That must have been in 1868 or 1869. He was then about eight years of age. My great-grandmother took a great interest in him after discovering that he was the cleverest boy in the village, and he told me that he owed everything to her. -

The Messenger February – March 2020

The Messenger February – March 2020 Rector, the Reverend Canon Káren Jongman 01327 830 569 | 07980 881 252 [email protected] Honorary Assistant Priest (Retired), The Reverend Hugh Kent Reader: Sue Titheridge Certified Lay Worship Leader: Jean Pugh 07711 329 664 Churchwardens Cold Higham Pauline Pearson 01327 830 287 Gayton David Coppock 01604 859 645 Andy Hartley 01604 858 360 Pattishall Chris Bulleid 07934 589 685 Julie Bunker 07773 131 107 Tiffield Mike Dean 01327 350 077 Philip Titheridge 01327 351 219 A Note from Peterborough Diocese ‘Saying Yes to Life’ – Lent and Lambeth 2020 This summer, almost 1,000 bishops from all over the world will be gathering in Canterbury for the Lambeth Conference. Some of the bishops, including from our link dioceses in Korea, will be spending a few days beforehand at Launde Abbey with Bishop Donald and myself. A key theme of the conference will be the global climate emergency that is already impacting the dioceses from which some of the bishops serve. For example, low-lying areas flooded by rising sea-levels and conflict triggered by expanding deserts, forcing people to move and compete for scarce land. Archbishop Justin has recorded a short interview highlighting this aspect of Lambeth 2020. You can view it here. As we approach the season of Lent I’d like to commend two ways in which we can engage with these important matters from the perspective of our Christian faith: The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Lent Book, Saying Yes to Life by Ruth Valerio, is a brilliant exploration of what it means to look after God’s world, reflecting on creation themes including light, water, land and seasons alongside environmental concerns. -

October 2008

Bugbrooke L I N K www.bugbrookelink.co.uk October 2008 RON COPSON Painter & Decorator FREE ESTIMATES ‘Zimmerman’ 33, Close Road, Nether Heyford Northants NN7 3LW Telephone 01327 349162 City & Guilds Qualified * All Weather Pitch Sport & Leisure * Pottery Workshops at & Art Rooms * Sports Hall * 200 seat Hall For more information or to with Stage make a booking call Gavin * Tennis Courts Rowe or Gillian Stone on * Music Rooms 01604 833900 * Gymnasium * Drama Studio * Classroom, Training & Conference Facilities The Bugbrooke “LINK” Committee Published bi-monthly. Circulated free to every household within the Parish boundary of Bugbrooke. The “LINK” Management Committee is elected in ac- cordance with the Constitution and Rules at the A.G.M. in May annually. Editor/Chairman Paul Cockcroft, 31 Pilgrims Lane Deputy Editor Tony Pace, 4 Laddermakers Yard Production & Website Geoff Cooke, 1 Browns Yard Secretary/News Gathering Barbara Bell, 68 Chipsey Avenue Treasurer/Vice Chairman Jim Inch, 16a High Street Advertising Sheila Willmore, 31 Oaklands Production & Development Donna Bowater, 57 Leys Rd., Pattishall E‐mail to [email protected] Web site address www.bugbrookelink.co.uk Deadline for December issue 3rd November 2008 Whilst we check the information for grammar and spelling on articles supplied by our contributors, the LINK magazine can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions in the factual content of the information. The views expressed in these articles are those of the contributors and are not necessarily shared by the -

No. 184 March- April 2013

Around Pattishall March-April 2013 No. 184 March- April 2013 Photo by Paul Howard 07977 558067 www.paulhoward.co.uk Final copy date for the May - June 2013 newsletter is 10th April. Copy should be sent to Andy Stewart, The Old Farmhouse, 13 High Street, Astcote (email [email protected], tel: 830042), or given to Janet Taylor, Dalscote. (Please use email if possible.) Pattishall Parish Council undertakes the production of the newsletter, it does not take responsibility for the accuracy of articles. Any views or opinions expressed are those of the author in each case. Would you like to see your photograph or artwork on the cover of the next Around Pattishall? If so, please send it to me. It should be something1 with a local & seasonal flavour. Around Pattishall March-April 2013 Village Spring Clean This years event will take place on Saturday 16th March 2013. Meet at the village Hall at 9am. For those who have not helped before we cleanup the litter and rubbish from the roadside verges before the vegetation grows. If you could spare an hour or so you would be most welcome. High Viz vests are provided as well as litter pickers and bags. Please let me know if you can help. John Woollett [email protected] or 830470 Pattishall Women’s Institute Our December meeting took place in a very cold Village Hall, yet we managed to enjoy it, in spite of having to spend the evening wearing our coats, hats and scarves. Shirley Allen had us laughing at mistakes in English, the refreshments were good and Secret Santa did not disappoint. -

Extended Phase 1 Report

Extended Phase 1 Report JLL Sports Field adjacent to Wootton Hall Park, Northampton – including additional area and access Ref: 15-3271 3983 01 Version: 4 Date: June 2016 Author: James Hildreth Reviewer: Samantha Hodgson Address: 7-8 Melbourne House Corbygate Business Park Weldon Corby Northamptonshire NN17 5JG Tel: 01536 408840 Executive Summary Executive Summary Lockhart Garratt Ltd was commissioned by JLL to carry out an Extended Phase 1 Habitat Survey including desk study for land at Wootton Hall Park. The survey also included a ground based evaluation of the trees within the site boundary for their potential to support roosting bats. An additional area and access was added to the proposals in early June 2016 and a second site visits and updated report was prepared. There were 5 statutory designated sites revealed within the desk study and 12 non-statutory sites within 2km of the Site, with Wootton Railway embankment, a local wildlife site, approximately 1km away. A range of protected mammal, amphibian and reptile species were identified within 2km of the Site by the desk study. The Extended Phase 1 Survey was undertaken on 8th March 2016 with an update to the assessment completed on 1st June 2016. The habitat within the Site consisted of an extensive area of regularly managed amenity grassland used as a sports pitch, with associated hardstanding. The hardstanding and amenity grassland were considered to be of low ecological value. The mature scattered trees along the western and southern boundary of the Site had a higher ecological value. The additional area consisted of access road and parking (hardstanding) with amenity grassland and standard trees the same as found in the original survey of the adjoining area. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Stratford-Upon-Avoh Festival

A H A N D BOO K TO THE STRATFO RD - U PON - AVON FESTIVAL A Handb o o k to the St rat fo rd- u p o n- A V O H Fe st iv al WITH ART I C LE S BY N R . B N O F . E S ARTHUR HUTCHINSO N N R EG I A L D R . B UC K L EY CECI L SH RP J. A A ND [ LL USTRA TI ONS P UBLI SHED UNDER TH E A USPICES A ND WITH THE SPECIAL SANCTION OF TH E SHAKESPEARE M EMORIAL COUNCI L LONDON NY L GEO RGE ALLEN COM PA , T D. 44 45 RATH B ONE P LA CE I 9 1 3 [All rig hts reserved] P rinted b y A L L A NT Y NE A NSON ér' B , H Co . A t the Ballant ne P ress y , Edinb urg h P R E F A IC E “ T H E Shakespeare Revival , published two years ago , has familiarised many with the ideas inseparable from any national dramatic Festival . But in that book one necessarily Opened up vistas of future development beyond the requirements of those who desire a Hand a book rather than Herald of the Future . For them an abridgment and revision are effected here . Also there are considerable additions , and Mr . Cecil J . Sharp contributes a chapter explaining the Vacation School of Folk Song o f and Dance , which he became Director since the previous volume was issued . The present volume is intended at once to supplement and no t condense , to supersede , the library edition . -

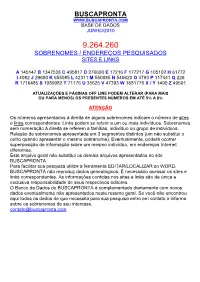

Buscapronta Base De Dados Junho/2010

BUSCAPRONTA WWW.BUSCAPRONTA.COM BASE DE DADOS JUNHO/2010 9.264.260 SOBRENOMES / ENDEREÇOS PESQUISADOS SITES E LINKS A 145147 B 1347538 C 495817 D 276690 E 17216 F 177217 G 105102 H 61772 I 4082 J 29600 K 655085 L 42311 M 550085 N 540620 O 4793 P 117441 Q 226 R 1716485 S 1089982 T 71176 U 35625 V 47393 W 1681776 X / Y 1490 Z 49591 ATUALIZAÇÕES E PÁGINAS OFF LINE PODEM ALTERAR (PARA MAIS OU PARA MENOS) OS PRESENTES NÚMEROS EM ATÉ 5% A 8% ATENÇÃO Os números apresentados à direita de alguns sobrenomes indicam o número de sites e links correspondentes. Links podem se referir a um ou mais indivíduos. Sobrenomes sem numeração à direita se referem a famílias, indivíduo ou grupo de indivíduos. Relação de sobrenomes apresentada em 3 segmentos distintos (um não substitui o outro quando apresentar o mesmo sobrenome). Eventualmente, poderá ocorrer superposição de informação sobre um mesmo indivíduo, em endereços Internet diferentes. Este arquivo geral não substitui os demais arquivos apresentados no site BUSCAPRONTA. Para facilitar sua pesquisa utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR so WORD. BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos. È necessário acessar os sites e links correspondentes. As informações contidas nos sites e links são de única e exclusiva responsabilidade de seus respectivos editores. O Banco de Dados do BUSCAPRONTA é complementado diariamente com novos dados eventualmente não apresentados neste resumo geral. Se você não encontrou aqui todos os dados de que necessita para sua pesquisa entre em contato e informe sobre os sobrenomes