English Justices and Roman Jurists: the Civilian Learning Behind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CCBE Contribution for the Rule of Law Report 2021 (26/03/2021)

CCBE Contribution for the Rule of Law Report 2021 26/03/2021 Introduction The Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) represents the bars and law societies of 45 countries and, through them, more than 1 million European lawyers. The CCBE also acts as a consultative and intermediary body between its Members and between the Members and the institutions of the European Union on cross-border matters of mutual interest. The regulation of the profession, the defence of the rule of law, human rights and democratic values are the most important missions of the CCBE. Several areas of special concern to the CCBE include access to justice, the development of the rule of law, the respect for the right to a defence and the effectiveness of the Justice system, which are core values of the profession. The CCBE always places a great emphasis on the respect for the rule of law, democratic principles and fundamental rights. The values of the CCBE and its Member organisations are consistent with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, and in particular its preamble, where it is stated, inter alia that “Conscious of its spiritual and moral heritage, the Union is founded on the indivisible, universal values of human dignity, freedom, equality and solidarity; it is based on the principles of democracy and the rule of law. It places the individual at the heart of its activities, by establishing the citizenship of the Union and by creating an area of freedom, security and justice”, CCBE values are also consistent with Article 47 (Rights to an effective remedy and to a fair trial), Article 48 (Presumption of innocence and right to a defence), and Article 49 (Principles of legality and proportionality of criminal offences and penalties). -

Final Report

Jamaican Justice System Reform Task Force Final Report June 2007 Jamaican Justice System Reform Task Force (JJSRTF) Prof. Barrington Chevannes, Chair The Hon. Mr. Justice Lensley Wolfe, O.J. (Chief Justice of Jamaica) Mrs. Carol Palmer, J.P. (Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Justice) Mr. Arnaldo Brown (Ministry of National Security) DCP Linval Bailey (Jamaica Constabulary Force) Mr. Dennis Daly, Q.C. (Human Rights Advocate) Rev. Devon Dick, J.P. (Civil Society) Mr. Eric Douglas (Public Sector Reform Unit, Cabinet Office) Mr. Patrick Foster (Attorney-General’s Department) Mrs. Arlene Harrison-Henry (Jamaican Bar Association) Mrs. Janet Davy (Department of Correctional Services) Mrs. Valerie Neita Robertson (Advocates Association) Miss Lisa Palmer (Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions) The Hon. Mr. Justice Seymour Panton, C.D. (Court of Appeal) Ms. Donna Parchment, C.D., J.P. (Dispute Resolution Foundation) Miss Lorna Peddie (Civil Society) Miss Hilary Phillips, Q.C. (Jamaican Bar Association) Miss Kathryn M. Phipps (Jamaica Labour Party) Mrs. Elaine Romans (Court Administrators) Mr. Milton Samuda/Mrs. Stacey Ann Soltau-Robinson (Jamaica Chamber of Commerce) Mrs. Jacqueline Samuels-Brown (Advocates Association) Mrs. Audrey Sewell (Justice Training Institute) Miss Melissa Simms (Youth Representative) Mr. Justice Ronald Hugh Small, Q.C. (Private Sector Organisation of Jamaica) Her Hon. Ms. Lorraine Smith (Resident Magistrates) Mr. Carlton Stephen, J.P. (Lay Magistrates Association) Ms. Audrey Thomas (Public Sector Reform Unit, Cabinet Office) Rt. Rev. Dr. Robert Thompson (Church) Mr. Ronald Thwaites (Civil Society) Jamaican Justice System Reform Project Team Ms. Robin Sully, Project Director (Canadian Bar Association) Mr. Peter Parchment, Project Manager (Ministry of Justice) Dr. -

Pratt's Government Contracting

0001 [ST: 1] [ED: m] [REL: 20-12GT] (Beg Group) Composed: Mon Nov 16 10:32:03 EST 2020 XPP 9.3.1.0 FM000150 nllp 4938 [PW=468pt PD=693pt TW=336pt TD=528pt] VER: [FM000150-Master:03 Oct 14 02:10][MX-SECNDARY: 11 Aug 20 13:11][TT-: 02 Jul 20 09:46 loc=usa unit=04938-fmvol006] 0 PRATT’S GOVERNMENT CONTRACTING LAW REPORT VOLUME 6 NUMBER 12 December 2020 Editor’s Note: Guidance Victoria Prussen Spears 407 Department of Defense Overhauls Contractor Information Security Requirements Through Its Interim Rule Implementing the CMMC and DoD NIST SP 800-171 Assessment Methodology Thomas Pettit, Ronald D. Lee, Charles A. Blanchard, and Tom McSorley 410 Defense Department Guidance for Government Contractors on Additional COVID-19-Related Costs Joseph R. Berger, Thomas O. Mason, and Francis E. Purcell, Jr. 419 Federal Contractors May Face Immigration-Related Hiring Requirements and Barriers Paul R. Hurst, Elizabeth Laskey LaRocca, Dana J. Delott, and Caitlin Conroy 422 What the “Essential Medicines” Executive Order Means for Federal Contractors and the FDA James W. Kim, Brian J. Malkin, Peter M. Routh, and Gugan Kaur 427 Federal Circuit Revives Key Case Addressing Contractor’s Ability to Include Offsets in Measurement of CAS Change Impacts Kevin J. Slattum, Aaron S. Ralph, and Dinesh Dharmadasa 433 Eleventh Circuit Rules on FCA Materiality and Litigation Funding Agreements Matthew J. Oster 438 0002 [ST: 1] [ED: m] [REL: 20-12GT] Composed: Mon Nov 16 10:32:03 EST 2020 XPP 9.3.1.0 FM000150 nllp 4938 [PW=468pt PD=693pt TW=336pt TD=528pt] VER: [FM000150-Master:03 Oct 14 02:10][MX-SECNDARY: 11 Aug 20 13:11][TT-: 02 Jul 20 09:46 loc=usa unit=04938-fmvol006] 47 QUESTIONS ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION? For questions about the Editorial Content appearing in these volumes or reprint permission, please call: Heidi A. -

2021 Rule of Law Report - Targeted Stakeholder Consultation

2021 Rule of Law Report - targeted stakeholder consultation Submission by ILGA-Europe and member organisations Arcigay & Certi Diritti (Italy); Bilitis, GLAS Foundation & Deystvie (Bulgaria); Çavaria (Belgium - Flanders); Háttér Társaság (Hungary); Legebrita (Slovenia); PROUD (Czech Republic); RFSL (Sweden) and Zagreb Pride (Croatia). ILGA-Europe are an independent, international LGBTI rights non-governmental umbrella organisation bringing together over 600 organisations from 54 countries in Europe and Central Asia. We are part of the wider international ILGA organisation, but ILGA-Europe were established as a separate region of ILGA and an independent legal entity in 1996. ILGA itself was created in 1978. https://www.ilga-europe.org/who- we-are/what-ilga-europe Contents Horizontal developments ........................................................................................................................ 2 Belgium ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bulgaria ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Croatia .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Czech Republic ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Hungary -

Pratt's Government Contracting

0001 [ST: 1] [ED: m] [REL: 20-12GT] (Beg Group) Composed: Mon Nov 16 10:32:03 EST 2020 XPP 9.3.1.0 FM000150 nllp 4938 [PW=468pt PD=693pt TW=336pt TD=528pt] VER: [FM000150-Master:03 Oct 14 02:10][MX-SECNDARY: 11 Aug 20 13:11][TT-: 02 Jul 20 09:46 loc=usa unit=04938-fmvol006] 0 PRATT’S GOVERNMENT CONTRACTING LAW REPORT VOLUME 6 NUMBER 12 December 2020 Editor’s Note: Guidance Victoria Prussen Spears 407 Department of Defense Overhauls Contractor Information Security Requirements Through Its Interim Rule Implementing the CMMC and DoD NIST SP 800-171 Assessment Methodology Thomas Pettit, Ronald D. Lee, Charles A. Blanchard, and Tom McSorley 410 Defense Department Guidance for Government Contractors on Additional COVID-19-Related Costs Joseph R. Berger, Thomas O. Mason, and Francis E. Purcell, Jr. 419 Federal Contractors May Face Immigration-Related Hiring Requirements and Barriers Paul R. Hurst, Elizabeth Laskey LaRocca, Dana J. Delott, and Caitlin Conroy 422 What the “Essential Medicines” Executive Order Means for Federal Contractors and the FDA James W. Kim, Brian J. Malkin, Peter M. Routh, and Gugan Kaur 427 Federal Circuit Revives Key Case Addressing Contractor’s Ability to Include Offsets in Measurement of CAS Change Impacts Kevin J. Slattum, Aaron S. Ralph, and Dinesh Dharmadasa 433 Eleventh Circuit Rules on FCA Materiality and Litigation Funding Agreements Matthew J. Oster 438 0002 [ST: 1] [ED: m] [REL: 20-12GT] Composed: Mon Nov 16 10:32:03 EST 2020 XPP 9.3.1.0 FM000150 nllp 4938 [PW=468pt PD=693pt TW=336pt TD=528pt] VER: [FM000150-Master:03 Oct 14 02:10][MX-SECNDARY: 11 Aug 20 13:11][TT-: 02 Jul 20 09:46 loc=usa unit=04938-fmvol006] 47 QUESTIONS ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION? For questions about the Editorial Content appearing in these volumes or reprint permission, please call: Heidi A. -

How Did Henry Bracton's Writing Reflect the Status of Kingship And

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 2, Issue 10: 104-107, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2020.021020 How Did Henry Bracton’s Writing Reflect the Status of Kingship and barons’ Power in Medieval England? Xue Aiyi Shanghai Shixi Highschool, Shanghai 200040, China ABSTRACT. Status and change of kingship and barons’ power in medieval England have a significant effect in the development of western society, politics, and justice. Thus, opinions and records form jurists in medieval England partially reflected the change in nature of justice and society, which led absolute monarchy to become constitutional monarchy. On the basis of previous studies, this paper specifically focus on writings of Henry de Bracton, an English jurist, aiming to provide further distinctive opinions by analyzing his writings. The content of this paper is divided into three parts altogether: The first part is chapter one, introducing Henry de Bracton, his works, and their value for understanding nature of justice and society status in medieval England. The second part is from chapter two to chapter five, analyzing status of kingship and barons’ power reflected in De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae, Magna Carta, and Bracton’s notebook, detailly interpreting the legal articles and practical law cases in medieval England. The third part is chapter six, concluding the whole paper and summing up main arguments. KEYWORDS: Medieval england, Henry de bracton, Kingship, Barons’power 1. Introduction Henry de Bracton (c.1210-1268) was an English jurist. As the Magna Carta was signed in 1215, it can be deduced that he lived in the period that barons began to have conflicts with the kingship in England, and it was also the time period that the Angevin Empire appeared to be declining. -

What to Do When You Are Served with a Search Warrant by Manny A

AN A.S. PRATT PUBLICATION APRIL 2016 PRATT’S PRATT’S VOL. 2 • NO. 3 PRIVACY & CYBERSECURITY LAW CYBERSECURITY & PRIVACY PRATT’S PRIVACY & CYBERSECURITY REPORT LAW REPORT EDITOR’S NOTE: SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE! THE FTC, UNFAIR PRACTICES, AND Steven A. Meyerowitz CYBERSECURITY: TWO STEPS FORWARD, AND TWO STEPS BACK WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU ARE SERVED WITH A David Bender SEARCH WARRANT APRIL Manny A. Abascal and Robert E. Sims DRONES AT HOME: DHS PUBLISHES BEST PRACTICES FOR PROTECTING PRIVACY, CIVIL PRESIDENT OBAMA SIGNS CYBERSECURITY RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN DOMESTIC 2016 ACT OF 2015 TO ENCOURAGE CYBERSECURITY UAS PROGRAMS INFORMATION SHARING Charles A. Blanchard, David J. Weiner, Kenneth L. Wainstein, Keith M. Gerver, Tom McSorley, and Elizabeth T.M. Fitzpatrick and Peter T. Carey VOL. VOL. A SKIMPY RISK ANALYSIS IS RISKY BUSINESS 2 FOR HIPAA COVERED ENTITIES AND • BUSINESS ASSOCIATES NO. Kimberly C. Metzger 3 What to Do When You Are Served With a Search Warrant By Manny A. Abascal and Robert E. Sims* Most business executives and officers lack the training and preparation to deal effec- tively with a search warrant. In order to protect privacy and other rights, this article sets forth the basic principles that should govern preparation for, and response to, a search warrant. State and federal law enforcement agencies continue to increase their investigation and prosecution of white collar crime, particularly relating to the securities and health- care industries. The search warrant has become a regular method authorities use to obtain evidence. Law enforcement officers executing a warrant typically arrive at corporate offices with no prior notice, armed with a search warrant entitling them to seize original business records, including computer records. -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Eric J. Hobsbawm, Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959). 2. Eric J. Hobsbawm, Bandits, rev. ed. (1961; New York: Pantheon, 1981), p. 23. 3. Ibid., p. 17. 4. Ibid., pp. 22–28. 5. Anton Blok, “The Peasant and the Brigand: Social Banditry Reconsidered,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 1:4 (1972), 494–503. See also Richard W. Slatta, ed., Bandidos: The Varieties of Latin American Banditry (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1987). 6. See the summary by Richard W. Slatta, “Eric J. Hobsbawm’s Social Bandit: A Critique and Revision,” A Contracorriente 1:2 (2004), 22–30. 7. Paul Kooistra, Criminals as Heroes: Structure, Power, and Identity (Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1989), p. 29. 8. See Steven Knight’s Robin Hood: A Complete Study of the English Outlaw (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994); and Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003). 9. Mary Grace Duncan, Romantic Outlaws, Beloved Prisons: the Unconscious Meanings of Crime and Punishment (New York: New York University Press, 1996), p. 61. 10. Charles Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (London, 1841). 11. See, for instance, Kenneth Munden, “A Contribution to the Psychological Understanding of the Cowboy and His Myth,” American Imago Summer (1958), 103–48. 12. William Settle, for instance, makes the argument in the introduction to his Jesse James Was His Name (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1966). 13. Hobsbawm, Bandits, pp. 40–56. 14. Joseph Ritson, ed., Robin Hood: A Collection of all the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, now Extant Relative to that Celebrated English Outlaw, 2 vols (London: Egerton and Johnson, 1795; rpt. -

Women and Crime in Sixteenth-Century Wales

Women and Crime in Sixteenth-Century Wales Elizabeth Anne Howard A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University 2020 i Summary This thesis is the first full-length study of women and crime in sixteenth-century Wales. After the Acts of Union of 1536 and 1543, Wales fell under English legal jurisdiction. As such, Wales provides a key setting through which to question how a new system of criminal law could be developed and implemented. The sixteenth- century, however, has been somewhat neglected by historians of crime, as has the location of Wales. This study addresses this gap in research by utilising the detailed depositional evidence from the Welsh Great Sessions c.1542 to 1590. Further, this thesis draws especially on evidence from Montgomeryshire and Flintshire due to the richness of the surviving source material in these counties’ gaol files, and the fact that these two counties were part of the same Great Sessions circuit. Compared to the history of Welsh crime, the study of gender and crime has been much more vibrant. This thesis builds on previous research in this field by placing women’s experience as perpetrators and victims of crime at the forefront of the investigation. Throughout, I examine the three main categories of offence that women experienced – theft, homicide, and witchcraft – and question how a woman’s gender affected her treatment before the law. Indeed, the central arguments of these chapters expose the differences between criminal accusations made against women in their original formats and how these allegations could be modified and changed throughout the legal process. -

Henry De Bracton

Henry de Bracton Carved on the grand portico of the Harvard University Law School Library, in letters as tall as a man, is “NON SUB HOMINE SED SUB DEO ET LEGE”. It is a simple but profound statement: “not under Man but under God and the Law” and Henry de Bracton, the greatest of our Prebendaries wrote it. Harvard University Law School Library Before going there, though, let us look at the state of Wells when Henry de Bracton arrived in Wells the 1240s. From 1090, Wells had suffered a century of decline. It lost its Bishop to Bath. Later, a greedy Bishop Savaric FitzGelderwin forcibly annexed Glastonbury Abbey to the Diocese, now called Bath and Glastonbury. Dastardly deeds filled the years - fixed elections, nepotism and murder. Things were at rock bottom when Savaric, away as usual, this time in Rome, died in 1205. The Canons of Wells seized the day, agreed rules of election with the monks of Bath and, together, they elected Jocelin of Wells. Jocelin ended the Glastonbury tie. Regaining independence cost the Abbey dear – the price was four manors - and the Abbey monks felt sore. Then in 1219, through a Papal Bull, Hororarius III created the Diocese of Bath and Wells we know today. Jocelin started rebuilding the Cathedral and bequeathed his body for burial there. Wells was again at the heart of the Diocese when Jocelin died there in 1242. In the monasteries of Bath and Glastonbury, though, Wells had enemies. The monks of Bath had buried the Bishops there for 150 years and felt humiliated. -

Northamptonshire Past & Present

~nqirnt and MODERN .... large or small. Fine building is synonymous with Robert Marriott Ltd., a member of the Robert Marriott Group, famous for quality building since 1890. In the past 80 years Marriotts have established a reputation for meticulous craftsmanship on the largest and small est scales. Whether it is a £7,000,000 housing contract near Bletchley, a new head quarters for Buckinghamshire County Council at Aylesbury (right) or restor ation and alterations to Easton Maudit Church (left) Marriotts have the experi ence, the expertise and the men to carry out work of the most exacting standards and to a strict schedule. In the last century Marriotts made a name for itself by the skill of its crafts men employed on restoring buildings of great historical importance. A re markable tribute to the firm's founder, the late Mr. Robert Marriott was paid in 1948 by Sir Albert Richardson, later President of the Royal Academy, when he said: "He was a master builder of the calibre of the Grimbolds and other famous country men. He spared no pains and placed ultimate good before financial gain. No mean craftsman him self, he demanded similar excellence from his helpers." Three-quarters of a century later Marriotts' highly specialised Special Projects Division displays the same inherent skills in the same delicate work on buildings throughout the Midlands. To date Hatfield House, Long Melford Hall in Suffolk, the Branch Library at Earls Barton, the restoration of Castle Cottage at Higham Ferrers, Fisons Ltd., Cambridge, Greens Norton School, Woburn Abbey restorations and the Falcon Inn, Castle Ashby, all bear witness to the craftsmanship of Marriotts. -

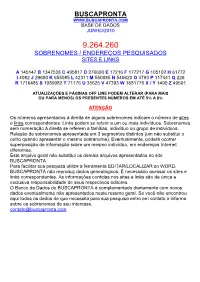

Buscapronta Base De Dados Junho/2010

BUSCAPRONTA WWW.BUSCAPRONTA.COM BASE DE DADOS JUNHO/2010 9.264.260 SOBRENOMES / ENDEREÇOS PESQUISADOS SITES E LINKS A 145147 B 1347538 C 495817 D 276690 E 17216 F 177217 G 105102 H 61772 I 4082 J 29600 K 655085 L 42311 M 550085 N 540620 O 4793 P 117441 Q 226 R 1716485 S 1089982 T 71176 U 35625 V 47393 W 1681776 X / Y 1490 Z 49591 ATUALIZAÇÕES E PÁGINAS OFF LINE PODEM ALTERAR (PARA MAIS OU PARA MENOS) OS PRESENTES NÚMEROS EM ATÉ 5% A 8% ATENÇÃO Os números apresentados à direita de alguns sobrenomes indicam o número de sites e links correspondentes. Links podem se referir a um ou mais indivíduos. Sobrenomes sem numeração à direita se referem a famílias, indivíduo ou grupo de indivíduos. Relação de sobrenomes apresentada em 3 segmentos distintos (um não substitui o outro quando apresentar o mesmo sobrenome). Eventualmente, poderá ocorrer superposição de informação sobre um mesmo indivíduo, em endereços Internet diferentes. Este arquivo geral não substitui os demais arquivos apresentados no site BUSCAPRONTA. Para facilitar sua pesquisa utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR so WORD. BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos. È necessário acessar os sites e links correspondentes. As informações contidas nos sites e links são de única e exclusiva responsabilidade de seus respectivos editores. O Banco de Dados do BUSCAPRONTA é complementado diariamente com novos dados eventualmente não apresentados neste resumo geral. Se você não encontrou aqui todos os dados de que necessita para sua pesquisa entre em contato e informe sobre os sobrenomes