Appendix: Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 “Though His Working Life Has Been Passed Chiefly on the Far Shores of the C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

Blackmail in the Deep State

Blackmail in the Deep State: From the Bay of Pigs and JFK Assassination to Watergate Jonathan Marshall Note: this article is excerpted from an unpublished book titled Watergate, the American Deep State, and the Legacy of Secret Government by Jonathan Marshall. The Watergate affair of 1972-74, though widely regarded as one of the the gravest political and constitutional crises in U.S. history, began not with a bang but a whimper – or as President Nixon’s press secretary dismissed it, a ‘third-rate burglary attempt’.1 Despite myriad government probes, lawsuits, news stories, and scholarly analyses, no one knows for sure what motivated the historic break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters during the 1972 presidential campaign.2 Another unresolved puzzle is why President Nixon, who was apparently ignorant of plans for the burglary, did not simply fire those involved and cut his losses. What cost him the presidency was not the original crime, but his illegal attempt to cover it up. I argue in the book from which this article is excerpted that the initial burglary was set in motion by White House insiders to uncover information they could use against the Democratic Party’s chairman, Larry O’Brien. A major goal was to prevent him from releasing politically damaging secrets 1 Quoted in Karlyn Barker and Walter Pincus, ‘Watergate Revisited; 20 Years After the Break-in, the Story Continues to Unfold’, Washington Post, 14 June 1992. 2 There were at least two break-ins; police arrested the burglars on 17 June 1972. Several dozen theories are noted in Edward Epstein and John Berendt, ‘Did There Come a Point in Time When There Were 43 Different Theories of How Watergate Happened?’ Esquire, November 1973. -

Jacksonville Civil Rights History Timelinetimeline 1St Revision 050118

Jacksonville Civil Rights History TimelineTimeline 1st Revision 050118 Formatted: No underline REVISION CODES Formatted: Underline Formatted: Centered Strike through – delete information Yellow highlight - paragraph needs to be modified Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Centered Green highlight - additional research needed Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Highlight Grey highlight - combine paragraphs Formatted: Highlight Light blue highlight – add reference/footnote Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Highlight Grey highlight/Green underline - additional research and combine Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Highlight Red – keep as a reference or footnote only Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Thick underline, Underline color: Green, Highlight Formatted: Thick underline, Underline color: Green, Highlight Formatted: Highlight Formatted: No underline, Underline color: Auto Page 1 of 54 Jacksonville Civil Rights History TimelineTimeline 1st Revision 050118 Formatted: Font: Not Bold 1564 Fort Caroline was built by French Huguenots along St. Johns Bluff under the Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough command of Rene Goulaine de Laudonniere. The greater majority of the settlers Formatted: Strikethrough were also Huguenots, but were accompanied by a small number of Catholics, Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough agnostic and “infidels”. One historian identified the “infidels” as freemen from Formatted: Strikethrough Africa. Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough Formatted: Strikethrough 1813 A naturalized American citizen of British ancestry, Zephaniah Kingsley moved to Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough Fort George Island at the mouth of the St. Johns River. Pledging allegiance to Formatted: Strikethrough Spanish authority, Kingsley became wealthy as an importer of merchant goods, Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough seafarer, and slave trader. He first acquired lands at what is now the City of Orange Formatted: Strikethrough Park. There he established a plantation called Laurel Grove. -

"I Can't Breathe": Toward a Pneumatology of Singing and Missional Musicking for Racial Justice in Jacksonville, Florida

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Doctor of Pastoral Music Projects and Theses Perkins Thesis and Dissertations 5-28-2021 "I Can't Breathe": Toward a Pneumatology of Singing and Missional Musicking for Racial Justice in Jacksonville, Florida Thomas Shapard [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_music_etds Part of the Christianity Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Community-Based Learning Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Music Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Social Justice Commons Recommended Citation Shapard, Thomas, ""I Can't Breathe": Toward a Pneumatology of Singing and Missional Musicking for Racial Justice in Jacksonville, Florida" (2021). Doctor of Pastoral Music Projects and Theses. 4. https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_music_etds/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Perkins Thesis and Dissertations at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Pastoral Music Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. "1 CAN'T BREATHE": TOWARD A PNEUMATOLOGY OF SINGING AND MISSiONAL MUsICKING FOR RACIAL JUSTICE IN JACKSONVILLE. FLORIDA Thesis Approved with Honors by C.mara Run C. Michael Hawn University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Church Music Director. Doctor of Pastoral Music Program Marcell Steuernagel Assistant Professor of Church Music Director of Master of Sacred Music Program UlyssesV Owens Jr. Community Advisor Artistic Director Don't Miss A Beat. Inc. “I CAN’T BREATHE”: TOWARD A PNEUMATOLOGY OF SINGING AND MISSIONAL MUSICKING FOR RACIAL JUSTICE IN JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Perkins School of Theology Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Pastoral Music by Thomas M. -

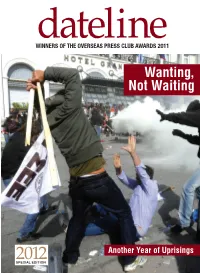

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

A List of the Records That Petitioners Seek Is Attached to the Petition, Filed Concurrently Herewith

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA IN RE PETITION OF STANLEY KUTLER, ) AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION, ) AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR LEGAL HISTORY, ) Miscellaneous Action No. ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS, ) and SOCIETY OF AMERICAN ARCHIVISTS. ) ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR ORDER DIRECTING RELEASE OF TRANSCRIPT OF RICHARD M. NIXON’S GRAND JURY TESTIMONY OF JUNE 23-24, 1975, AND ASSOCIATED MATERIALS OF THE WATERGATE SPECIAL PROSECUTION FORCE Professor Stanley Kutler, the American Historical Association, the American Society for Legal History, the Organization of American Historians, and the Society of American Archivists petition this Court for an order directing the release of President Richard M. Nixon’s thirty-five-year- old grand jury testimony and associated materials of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force.1 On June 23-24, 1975, President Nixon testified before two members of a federal grand jury who had traveled from Washington, DC, to San Clemente, California. The testimony was then presented in Washington, DC, to the full grand jury that had been convened to investigate political espionage, illegal campaign contributions, and other wrongdoing falling under the umbrella term Watergate. Watergate was the defining event of Richard Nixon’s presidency. In the early 1970s, as the Vietnam War raged and the civil rights movement in the United States continued its momentum, the Watergate scandal ignited a crisis of confidence in government leadership and a constitutional crisis that tested the limits of executive power and the mettle of the democratic process. “Watergate” was 1A list of the records that petitioners seek is attached to the Petition, filed concurrently herewith. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Drugs, Crime, and the Justice System

u.s. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics •. B_uoflusti~Statistics .........' .' .•., .';'. '. ': , .' ",' .; • • , ~. • :'., • ' • • \ i"' .' ~ _. ~ " Technical Appendix Drugs, Crime, and the Justice System • U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justic~ Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Do you know ... Do you ever ... • what percentage of persons arrested /I need statistics on drug defendants for felony drug offenses are released and their sentences? on bail? • seek information on innovative Ell what proportion of felons convicted methods to expedite drug cases in State courts were convicted of through the court process? drug offenses? • have any questions about drug ., what proportion of felony drug testing programs? trafficking convictions result from a guilty plea? Are you ... • ever at a loss for a statistic? The Drugs & Crime Data Center & Clearinghouse has the answers to .. pressed for time? these questions and many more. e in a rush for information? The Data Center & Clearinghouse Call today ... @} operates a toll-free 800 number staffed by drugs and crime Drugs & Crime information specialists Data Center & ® answers requests for specific drug related data Clearinghouse .. maintains a data base of more than 2,000 drugs and crime citations 1-800-666-3332 .. performs bibliographic searches on The resource for drugs-and-crime data. specific topics • disseminates Bureau of Justice Statistics and other Department of The Drugs & Crime Data Center & Justice publications relating to qrugs Clearinghouse is a free service managed and crime by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and partially funded by the Bureau of • maintains a library and reading room Justice Assistance (BJA). ~ publishes reports on current topics of interest. -

Confidentiality Complications

Confidentiality Complications: How new rules, technologies and corporate practices affect the reporter’s privilege and further demonstrate the need for a federal shield law The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press June 2007 Lucy A. Dalglish, Esq. Gregg P. Leslie, Esq. Elizabeth J. Soja, Esq. 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, Virginia 22209 (703) 807-2100 Executive Summary The corporate structure of the news media has created new obstacles, both financial and practical, for journalists who must keep promises of confidentiality. Information that once existed only in a reporter’s notebook can now be accessed by companies that have obligations not only to their reporters, but to their shareholders, their other employees, and the public. Additionally, in the wake of an unprecedented settlement in the Wen Ho Lee Privacy Act case, parties can target news media corporations not just for their access to a reporter’s information, but also for their deep pockets. The potential for conflicts of interest is staggering, but the primary concerns of The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press are that: • because of the 21st-century newsroom’s reliance on technology, corporations now have access to notes, correspondence and work-product information that before only existed in a reporter’s notebook; • the new federal “e-discovery” court rules allow litigants to discover vastly more information than a printed page – or even a saved e-mail – would provide during litigation; • while reporters generally only have responsibilities to themselves, -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001

Technical Report 02-5 July 2002 Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001 Katherine L. Herbig Martin F. Wiskoff TRW Systems Released by James A. Riedel Director Defense Personnel Security Research Center 99 Pacific Street, Building 455-E Monterey, CA 93940-2497 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704- 0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DDMMYYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From – To) July 2002 Technical 1947 - 2001 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Katherine L. Herbig, Ph.D. Martin F. Wiskoff, Ph.D. 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

Thesis US Cuba.Pdf

BEING SUCCESSFULLY NASTY: THE UNITED STATES, CUBA AND STATE SPONSORED TERRORISM, 1959-1976 by ROBERT G. DOUGLAS B.A., University of Victoria, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History © Robert Grant Douglas, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. BEING SUCCESSFULLY NASTY: THE UNITED STATES, CUBA AND STATE SPONSORED TERRORISM, 1959-1976 by ROBERT G. DOUGLAS B.A., University of Victoria, 2005 Supervisory Committee Dr. Jason Colby (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Perry Biddiscombe (Department of History) Departmental Member Dr. Jordan Stanger-Ross (Department of History) Departmental Member Dr. Michelle Bonner (Department of Political Science) Outside Member ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Jason Colby (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Perry Biddiscombe (Department of History) Departmental Member Dr. Jordan Stanger-Ross (Department of History) Departmental Member Dr. Michelle Bonner (Department of Political Science) Outside Member Abstract Despite being the global leader in the “war on terror,” the United States has been accused of sponsoring terrorism against Cuba. The following study assesses these charges. After establishing a definition of terrorism, it examines U.S.-Cuban relations from 1808 to 1958, arguing that the United States has historically employed violence in its efforts to control Cuba. U.S. leaders maintained this approach even after the Cuban Revolution: months after Fidel Castro‟s guerrilla army took power, Washington began organizing Cuban exiles to carry out terrorist attacks against the island, and continued to support and tolerate such activities until the 1970s, culminating in what was the hemisphere‟s most lethal act of airline terrorism before 9/11.