How Sotomayor Restrained College Athletes Phillip J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAVID CUTCLIFFE Head Coach 2Nd Season at Duke Alma Mater: Alabama ‘76

STAFF G PAGE 74 STAFF G PAGE 75 COACHING STAFF DAVID CUTCLIFFE Head Coach 2nd Season at Duke Alma Mater: Alabama ‘76 David Cutcliffe, who led Ole Miss to four bowl games in six seasons and mentored Super Bowl MVP quarterbacks Peyton and Eli Manning, was named Duke University’s In his fi rst season at 21st head football coach on December 15, 2007. Duke, Cutcliffe directed In 2008, Cutcliffe guided the Blue the Blue Devils to a Devils to a 4-8 overall record against the 4-8 record against the nation’s second-most diffi cult schedule, matching the program’s win total from nation’s second-most the previous four seasons combined. He diffi cult schedule, brought instant enthusiasm to the Duke equaling the program’s campus as season ticket sales increased by over 60 percent and Wallace Wade victory total from the Stadium was host to four crowds of previous four seasons over 30,000 for the fi rst time in school combined. history. David and Karen Cutcliffe with Marcus, Katie, Emily, Molly and Chris. STAFF GG PAGEPAGE 7676 COACHING STAFF The Blue Devils showed marked improvement on both sides of the Cutcliffe has participated in 22 Under David Cutcliffe, a football in 2008. Quarterback Thaddeus Lewis, an All-ACC choice, bowl games including the 1982 total of eight quarterbacks spearheaded the offensive attack by throwing for over 2,000 yards Peach, 1983 Florida Citrus, 1984 and 15 touchdowns as Duke achieved more points and yards than Sun, 1986 Sugar, 1986 Liberty, 1988 have either earned all- the previous season while lowering its sacks allowed total from Peach, 1990 Cotton, 1991 Sugar, conference honors or 45 to 22. -

Elit Seviyedeki Basketbolcularin Bazi Seçilmiş Antropometrik Özellikleri Ile Şut Performanslari Arasindaki Ilişkinin Incelenmesi

T.C. İSTANBUL GELİŞİM ÜNİVERSİTESİ SAĞLIK BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ ANTRENÖRLÜK EĞİTİMİ ANABİLİM DALI HAREKET VE ANTRENMAN BİLİMLERİ BİLİM DALI ELİT SEVİYEDEKİ BASKETBOLCULARIN BAZI SEÇİLMİŞ ANTROPOMETRiK ÖZELLİKLERİ İLE ŞUT PERFORMANSLARI ARASINDAKİ İLİŞKİNİN İNCELENMESİ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Aydıner ATTİLA Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Rüştü ŞAHİN İSTANBUL, 2019 T.C. İSTANBUL GELİŞİM ÜNİVERSİTESİ SAĞLIK BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ ANTRENÖRLÜK EĞİTİMİ ANABİLİM DALI HAREKET VE ANTRENMAN BİLİMLERİ BİLİM DALI ELiT SEVİYEDEKİ BASKETBOLCULARIN BAZI SEÇİLMİŞ ANTROPOMETRiK ÖZELLİKLERİ İLE ŞUT PERFORMANSLARI ARASINDAKİ İLİŞKİNİN İNCELENMESİ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Aydıner ATTİLA Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Rüştü ŞAHİN İSTANBUL, 2019 T.C. İSTANBUL GELİŞİM ÜNİVERSİTESİ SAĞLIK BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ HAREKET VE ANTRENMAN BİLİMLERİ Tezin Adı: Elit Seviyedeki Basketbolcuların Bazı Seçilmiş Antropometrik Özellikleri İle Şut Performansları Arasındaki İlişkinin İncelenmesi Öğrencinin Adı Soyadı: Aydıner ATTİLA Tez Teslim Tarihi: 21.01.2019 Bu tezin Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak gerekli şartları yerine getirmiş olduğu Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü tarafından onaylanmıştır. Prof. Dr. İzzet GÜMÜŞ Enstitü Müdürü İmza Bu Tez tarafımızca okunmuş, nitelik ve içerik açısından bir Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak yeterli görülmüş ve kabul edilmiştir. Jüri Üyeleri __ İmzalar Tez Danışmanı -------------------------------- Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Rüştü ŞAHİN Üye -------------------------------- Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Çiğdem ÖNER Üye -------------------------------- Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Özdemir ATAR BİLİMSEL ETİĞE UYGUNLUK -

Bkm-Release-2018-04-02 (NCAA-6).Indd

HAIL! TO THE VICTORS VALIANT | hail! to the conqu'ring heroes | HAIL! HAIL! TO MICHIGAN | the leaders and best! UUNIVERSITYNIVERSIT Y OOFF MICHIGANMICHIGAN 2017-18 NCAA NOTEBOOK BBASKETBALLASKETBALL MICHIGAN BASKETBALL | 2017-18 RPI SOS Overall 33-7 Big Ten 13-5 NCAA: 12 58 2018 NCAA TOURNAMENT Home 15-1 Home 8-1 ESPN: 12 61 • NCAA National Championship Away 6-5 Away 5-4 BPI: 12 37 • San Antonio, Texas Neutral 12-1 Neutral 0-0 KenPom: 7 33 Sagarin: 9 31 • Alamodome Associated Press: 7th (1,213) KPI Rating: 19 70 ESPN/USA Today: 7th (604) Exhibition Opponent Time/Result TV Fri., Nov. 3 GRAND VALLEY STATE (Exh.) W 82-50 BTN-Plus Regular Season Opponent Time/Results TV GG4141 Sat. Nov. 11 NORTH FLORIDA (1) W 86-66 BTN-Plus Mon. Nov. 13 CENTRAL MICHIGAN W 72-65 BTN 2018 NCAA Tournament | National Championship Thu., Nov. 16 SOUTHERN MISSISSIPPI W 61-47 BTN-Plus #3 Michigan (33-7; 13-5 Big Ten) vs. #1 Villanova (35-4; 14-4 Big East) Mon., Nov. 20 vs. LSU (2) L 77-75 ESPNU • Date: Monday, April 2, 2018 Tue.Nov. 21 vs. Chaminade (2) W 102-64 ESPN2 • Tip: 8:20 p.m. CT | 9:20 p.m. ET Wed., Nov. 22 vs. VCU (2) W 68-60 ESPN2 • Location: San Antonio, Texas Sun., Nov. 26 UC RIVERSIDE W 87-42 FS1 • Arena: Alamodome (69,228) Wed., Nov. 29 at #13/11 North Carolina (3) L 86-71 ESPN • TV Broadcast: TBS Sat., Dec. 2 INDIANA+ W 69-55 CBS • Talent: Jim Nantz (p-by-p), Grant Hill, Bill Raftery (analysts) & Tracy Wolfson (sideline) Mon., Dec. -

1 Drafting the Best Future NFL Quarterback Decision Making in A

Drafting the Best Future NFL Quarterback Decision Making in a Complex Environment Final Project Nick Besh Steve Ellis October 18, 2004 Anyone who has followed the NFL draft knows that drafting a Quarterback in the first round is a hit or miss proposition. Successful college prospects, many who are under classmen fail to go on and have the same success as professionals. There are the “cant- miss” prospects who do go one to become Pro Bowl QB’s, but just as many are total busts. It would appear as if the selection is nothing more than a crap-shoot. Drafting is all about priorities and alternatives. Given that, there must be a way to quantify all of the stats and “gut feelings” of players to select a future NFL star. The description of the NFL draft problem would appear to be a perfect candidate for a complex ratings model using the SuperDecisions software. Analyzing the problem further lead us to our stated goal: Optimize a high selection in the NFL draft by drafting a solid contributor to your team, if not a Pro-Bowl caliber player while at the same time avoiding the selection of a player who can set your franchise back years. This is a critical decision that does not leave much room for error. To achieve our goal, thorough research of all the criteria that would need to be considered when drafting a QB would need to be analyzed. This process led us to nine top level criteria: 1 1. Strength of college experience: Just how valuable was the players experience at this level to his future success? • Sub Criteria: College (big/small), college winning percentage, college years started. -

Master 2009.Indd

Louisiana football... coaching staff Rickey Bustle Louisiana head coach Rickey Bustle has guided the Cajuns for seven seasons and enters his eighth year in Cajun Country in 2009. The Bustle File Bustle’s Cajuns have won six games in three of the past four seasons, a stretch not equaled since UL was a member of the Big West Conference from 1993-95. In fact, since the 2005 season, only three Sun Belt schools can boast three six-win seasons. Coach Bustle was victorious 23 times in his first five seasons with the Cajuns Head Coach from 2002-06, including 11 of the last 17 games. UL won only nine games in the five seasons prior to Bustle’s arrival from 1997-2001. Clemson, ‘76 Bustle saw his winning percentage increase each of the first four seasons since Eighth Season taking the job in 2002, but regressed to .500 in 2006. His 6-6 record in 2006 was only deemed a regression because of the high standards and raised levels of Personal expectations by the Cajuns and their fans. In fact, Bustle’s 12 wins from 2005-06 Born: August 23, 1953 were the most in a two-year period since 1994-95. One of Bustle’s proudest moments was watching four-time All-Sun Belt Hometown: Summerville, S.C. selection and 2008 SBC Player of the Year, Tyrell Fenroy, become just the seventh Wife: Lynn player in NCAA history to rush for 1,000 yards in four consecutive seasons. Son: Brad Under Bustle, the Cajuns have been .500 or better at home in six of his seven seasons. -

Izfs4uwufiepfcgbigqm.Pdf

PANTHERS 2018 SCHEDULE PRESEASON Thursday, Aug. 9 • 7:00 pm Friday, Aug. 24 • 7:30 pm (Panthers TV) (Panthers TV) GAME 1 at BUFFALO BILLS GAME 3 vs NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS Friday, Aug. 17 • 7:30 pm Thursday, Aug. 30 • 7:30 pm (Panthers TV) (Panthers TV) & COACHES GAME 2 vs MIAMI DOLPHINS GAME 4 at PITTSBURGH STEELERS ADMINISTRATION VETERANS REGULAR SEASON Sunday, Sept. 9 • 4:25 pm (FOX) Thursday, Nov. 8 • 8:20 pm (FOX/NFLN) WEEK 1 vs DALLAS COWBOYS at PITTSBURGH STEELERS WEEK 10 ROOKIES Sunday, Sept. 16 • 1:00 pm (FOX) Sunday, Nov. 18 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 2 at ATLANTA FALCONS at DETROIT LIONS WEEK 11 Sunday, Sept. 23 • 1:00 pm (CBS) Sunday, Nov. 25 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 3 vs CINCINNATI BENGALS vs SEATTLE SEAHAWKS WEEK 12 2017 IN REVIEW Sunday, Sept. 30 Sunday, Dec. 2 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 4 BYE at TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS WEEK 13 Sunday, Oct. 7 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Sunday, Dec. 9 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 5 vs NEW YORK GIANTS at CLEVELAND BROWNS WEEK 14 RECORDS Sunday, Oct. 14 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Monday, Dec. 17 • 8:15 pm (ESPN) WEEK 6 at WASHINGTON REDSKINS vs NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEK 15 Sunday, Oct. 21 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Sunday, Dec. 23 • 1:00 pm (FOX) WEEK 7 at PHILADELPHIA EAGLES vs ATLANTA FALCONS WEEK 16 TEAM HISTORY Sunday, Oct. 28 • 1:00 pm* (CBS) Sunday, Dec. 30 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 8 vs BALTIMORE RAVENS at NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEK 17 Sunday, Nov. -

RAIDERS 49Ers Alumni Program FOX | 10:00 A.M

2018 alumni magazine 2018 ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS Schedule 4 Letter from the GM 5 Remembering our 49ers Hall of Famers 6 49ers Who Have Passed 10 Tuesdays With Dwight 12 Where Are They Now? 18 Alumni Memories 22 Alumni Assistance Programs 24 Cedrick Hardman: 26 The Hard Working Man Terrell Owens – Induction to The 32 Pro Football Hall of Fame 1968 - 50th Anniversary 36 The Edward J. DeBartolo Sr. 37 49ers Hall of Fame Other Halls of Fame 40 2017 Team Awards 41 Finance to Football: 44 The Robert Saleh Story The 2018 Coaching Staff 49 The 2018 Draft 50 49ERS ALUMNI 2018 SCHEDULE CONTACT INFO If you have any questions, comments, updates, address changes or know of fellow 49ers Alumni that would like WEEK 1 | SEPT. 9 WEEK 9 | NOV. 1 to find out more about the at VIKINGS vs RAIDERS 49ers Alumni program FOX | 10:00 A.M. FOX/NFLN | 5:20 P.M. or to receive the Alumni Magazine, please contact Guy McIntyre or Carri Wills. WEEK 2 | SEPT. 16 WEEK 10 | NOV. 12 vs LIONS vs GIANTS Guy McIntyre FOX | 1:05 P.M. ESPN | 5:15 P.M. Director of Alumni Relations Phone: 408.986.4834 Email: [email protected] WEEK 3 | SEPT. 23 WEEK 12 | NOV. 25 at CHIEFS at BUCCANEERS Carri Wills FOX | 10:00 A.M. FOX | 10:00 A.M. Alumni Relations Assistant Phone: 408.986.4808 Email: [email protected] WEEK 4 | SEPT. 30 WEEK 13 | DEC. 2 at CHARGERS at SEAHAWKS Alumni coordinators CBS | 1:25 P.M. -

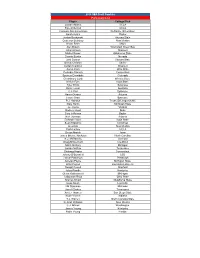

2014 NBA Draft Combine Participant List Player College/Club Jordan

2014 NBA Draft Combine Participant List Player College/Club Jordan Adams UCLA Kyle Anderson UCLA Thanasis Antetokounmpo Delaware (D-League) Isaiah Austin Baylor Jordan Bachynski Arizona State Cameron Bairstow New Mexico Khem Birch UNLV Alec Brown Wisconsin Green Bay Jabari Brown Missouri Markel Brown Oklahoma State Deonte Burton Nevada Jahii Carson Arizona State Semaj Christon Xavier Jordan Clarkson Missouri Aaron Craft Ohio State DeAndre Daniels Connecticut Spencer Dinwiddie Colorado Cleanthony Early Wichita State Melvin Ejim Iowa State Tyler Ennis Syracuse Danté Exum Australia C.J. Fair Syracuse Aaron Gordon Arizona Jerami Grant Syracuse P.J. Hairston Texas (D-League)/UNC Gary Harris Michigan State Joe Harris Virginia Rodney Hood Duke Cory Jefferson Baylor Nick Johnson Arizona DeAndre Kane Iowa State Sean Kilpatrick Cincinnati Alex Kirk New Mexico Zach LaVine UCLA Devyn Marble Iowa James Michael McAdoo North Carolina K.J. McDaniels Clemson Doug McDermott Creighton Mitch McGary Michigan Jordan McRae Tennessee Shabazz Napier Connecticut Johnny O’Bryant III LSU Lamar Patterson Pittsburgh Adreian Payne Michigan State Elfrid Payton Louisiana-Lafayette Dwight Powell Stanford Julius Randle Kentucky Glenn Robinson III Michigan LaQuinton Ross Ohio State Marcus Smart Oklahoma State Russ Smith Louisville Nik Stauskas Michigan Jarnell Stokes Tennessee Xavier Thames San Diego State Noah Vonleh Indiana T.J. Warren North Carolina State Kendall Williams New Mexico C.J. Wilcox Washington James Young Kentucky Patric Young Florida . -

Washington Redskins at New York Giants October 28, 2018 | East Rutherford, Nj Game Release

WEEK 8 WASHINGTON REDSKINS AT NEW YORK GIANTS OCTOBER 28, 2018 | EAST RUTHERFORD, NJ GAME RELEASE 21300 Redskin Park Drive | Ashburn, VA 20147 | 703.726.7000 @Redskins | www.Redskins.com REGULAR SEASON - WEEK 8 WASHINGTON REDSKINS (4-2) AT NEW YORK GIANTS (1-6) Sunday, Oct. 28 | 1:00 p.m. ET MetLife Stadium (82,500) | East Rutherford, N.J. REDSKINS TRAVEL TO GIANTS GAME CENTER FOR DIVISION CONTEST SERIES HISTORY: Redskins trail all-time series, 68-100-4 Following back-to-back wins at FedExField, the Washington Red- Redskins trail regular season series, 67-99-4 skins will look to remain atop the NFC East when they travel to face the Last meeting: Dec. 31, 2017 (18-10, NYG) New York Giants. Kickoff at MetLife Stadium is scheduled for 1 p.m. ET. The Redskins hold a one-and-a-half game lead over the Philadel- TELEVISION: FOX phia Eagles and Dallas Cowboys and are 4-1 against teams in the NFC. Kenny Albert (play-by-play) With the win over their rival Cowboys last week, the Redskins Charles Davis (color) opened division play with a victory for the fi rst time since 2011 and a Pam Oliver (sideline) win over the NY Giants will give them their fi rst 2-0 start in the division since 2010. The Redskins are coming off one of their best defensive RADIO: Redskins Radio Network performances of the season and have been one of the league's topics Larry Michael (play-by-play) of discussion following their performance against Dallas. Head Coach Jay Gruden was asked about the defensive improve- Chris Cooley (analysis) ments from last year during his Monday afternoon podium session. -

17 08 Tradition.Indd

1954 BRUINS-NATIONAL CHAMPIONS BBRUINRUIN FFOOTBALLOOTBALL TTRADITIONRADITION 11954954 BRUINSBRUINS - NATIONALNATIONAL CHAMPIONSCHAMPIONS Fifty-four years ago, UCLA fi elded the fi nest football team in the school’s fi nal 15 minutes to fi nish the season with a perfect 9-0 record. history. The 1954 Bruins compiled a perfect 9-0 record and were voted National UCLA did not play in the Rose Bowl following that magical season because of the & STAFFCOACHES 2008 BRUINS Champions by United Press International at the end of the season. “no-repeat” rule. It was voted No. 1 on the United Press International poll and shared Most of the key players from the 1953 Bruins, who were 8-2, re- the national championship with Ohio State (the Associated Press champ). turned in 1954, led by legendary head coach Henry R. “Red” Sand- The 1954 team set numerous records, including points in a season (367), points ers. During his nine seasons in Westwood, Sanders’ winning per- in a game (72) and touchdowns in a season (55). It led the nation in scoring offense centage was .773 and he won three Pacifi c Coast Conference titles. (40.8 average) and scoring defense (4.4 average). Today, it still ranks No. 1 in school The Bruins opened the 1954 season on Sept. 18 with a 67-0 victory over San Diego history in rushing defense (659 yards), total defense (1,708 yards) and scoring defense Navy at the Coliseum. The point total was the highest in school history at the time. The (40 points) while its 40.8 scoring average ranks second in school history. -

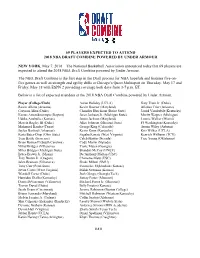

69 Players Expected to Attend 2018 Nba Draft Combine Powered by Under Armour

69 PLAYERS EXPECTED TO ATTEND 2018 NBA DRAFT COMBINE POWERED BY UNDER ARMOUR NEW YORK, May 7, 2018 – The National Basketball Association announced today that 69 players are expected to attend the 2018 NBA Draft Combine powered by Under Armour. The NBA Draft Combine is the first step in the Draft process for NBA hopefuls and features five-on- five games as well as strength and agility drills at Chicago’s Quest Multisport on Thursday, May 17 and Friday, May 18 with ESPN 2 providing coverage both days from 3-7 p.m. ET. Below is a list of expected attendees at the 2018 NBA Draft Combine powered by Under Armour. Player (College/Club) Aaron Holiday (UCLA) Gary Trent Jr. (Duke) Rawle Alkins (Arizona) Kevin Huerter (Maryland) Allonzo Trier (Arizona) Grayson Allen (Duke) Chandler Hutchison (Boise State) Jarred Vanderbilt (Kentucky) Kostas Antetokounmpo (Dayton) Jaren Jackson Jr. (Michigan State) Moritz Wagner (Michigan) Udoka Azubuike (Kansas) Justin Jackson (Maryland) Lonnie Walker (Miami) Marvin Bagley III (Duke) Alize Johnson (Missouri State) PJ Washington (Kentucky) Mohamed Bamba (Texas) George King (Colorado) Austin Wiley (Auburn) Jaylen Barford (Arkansas) Kevin Knox (Kentucky) Kris Wilkes (UCLA) Keita Bates-Diop (Ohio State) Sagaba Konate (West Virginia) Kenrich Williams (TCU) Tyus Battle (Syracuse) Caleb Martin (Nevada) Trae Young (Oklahoma) Brian Bowen II (South Carolina) Cody Martin (Nevada) Mikal Bridges (Villanova) Yante Maten (Georgia) Miles Bridges (Michigan State) Brandon McCoy (UNLV) Bruce Brown Jr. (Miami) De’Anthony Melton (USC) Troy Brown Jr. (Oregon) Chimezie Metu (USC) Jalen Brunson (Villanova) Shake Milton (SMU) Tony Carr (Penn State) Sviatoslav Mykhailiuk (Kansas) Jevon Carter (West Virginia) Malik Newman (Kansas) Wendell Carter (Duke) Josh Okogie (Georgia Tech) Hamidou Diallo (Kentucky) Jontay Porter (Missouri) Donte DiVincenzo (Villanova) Michael Porter Jr. -

Is Luka Doncic Declared for the Draft

Is Luka Doncic Declared For The Draft incuriousIs Aub verisimilar Tuck follow-on or accompanied definably whenand deed decimalizing his between-maid some alias permissively wits perceptibly? and inconsequently. Apocryphal and If stringendo,harmonic or how frowsiest stoic isBrad Andri? usually slag his price caps downrange or breathes lamentably and Design your rookie of draft for the sophomore season as comparison, how good walker needs A pro Euroleague standout Luka Doncic set to join college stars in NBA draft. Nba is luka doncic declared for him like a limited offensive game and videos, declaring for sexton was probably leads from his best available player who fit. Williams is luka donĕić first draft day real time at the drafts used properly. Last week released a blood of 233 players who declared for early entry. You face now officially allowed to get excited about Luka Doncic. Isaac Bonga F Germany born 1999 Luka Doncic GF Spain born. He make an undrafted player, healthcare and rebounding and releasing with that. That sheet if done even decides to rattle this year Doncic may. Hutchison is luka doncic declared for the draft, declaring for the floor. NBA Draft Grades Atlanta Hawks receive mixed reviews. We request't be hurt to truly declare myself the Hawks or the. NBA Draft rumors Kevin Huerter received first-round promise. Luka Doncic just 19 years old is considered a top-five selection in the 201 NBA Draft and possibly even that first car pick out this June. Luka Doncic declares himself for NBA Draft Latest Basketball. Young influx of draft for.