MANAGEMENT SCIENCE Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAVID CUTCLIFFE Head Coach 2Nd Season at Duke Alma Mater: Alabama ‘76

STAFF G PAGE 74 STAFF G PAGE 75 COACHING STAFF DAVID CUTCLIFFE Head Coach 2nd Season at Duke Alma Mater: Alabama ‘76 David Cutcliffe, who led Ole Miss to four bowl games in six seasons and mentored Super Bowl MVP quarterbacks Peyton and Eli Manning, was named Duke University’s In his fi rst season at 21st head football coach on December 15, 2007. Duke, Cutcliffe directed In 2008, Cutcliffe guided the Blue the Blue Devils to a Devils to a 4-8 overall record against the 4-8 record against the nation’s second-most diffi cult schedule, matching the program’s win total from nation’s second-most the previous four seasons combined. He diffi cult schedule, brought instant enthusiasm to the Duke equaling the program’s campus as season ticket sales increased by over 60 percent and Wallace Wade victory total from the Stadium was host to four crowds of previous four seasons over 30,000 for the fi rst time in school combined. history. David and Karen Cutcliffe with Marcus, Katie, Emily, Molly and Chris. STAFF GG PAGEPAGE 7676 COACHING STAFF The Blue Devils showed marked improvement on both sides of the Cutcliffe has participated in 22 Under David Cutcliffe, a football in 2008. Quarterback Thaddeus Lewis, an All-ACC choice, bowl games including the 1982 total of eight quarterbacks spearheaded the offensive attack by throwing for over 2,000 yards Peach, 1983 Florida Citrus, 1984 and 15 touchdowns as Duke achieved more points and yards than Sun, 1986 Sugar, 1986 Liberty, 1988 have either earned all- the previous season while lowering its sacks allowed total from Peach, 1990 Cotton, 1991 Sugar, conference honors or 45 to 22. -

1 Drafting the Best Future NFL Quarterback Decision Making in A

Drafting the Best Future NFL Quarterback Decision Making in a Complex Environment Final Project Nick Besh Steve Ellis October 18, 2004 Anyone who has followed the NFL draft knows that drafting a Quarterback in the first round is a hit or miss proposition. Successful college prospects, many who are under classmen fail to go on and have the same success as professionals. There are the “cant- miss” prospects who do go one to become Pro Bowl QB’s, but just as many are total busts. It would appear as if the selection is nothing more than a crap-shoot. Drafting is all about priorities and alternatives. Given that, there must be a way to quantify all of the stats and “gut feelings” of players to select a future NFL star. The description of the NFL draft problem would appear to be a perfect candidate for a complex ratings model using the SuperDecisions software. Analyzing the problem further lead us to our stated goal: Optimize a high selection in the NFL draft by drafting a solid contributor to your team, if not a Pro-Bowl caliber player while at the same time avoiding the selection of a player who can set your franchise back years. This is a critical decision that does not leave much room for error. To achieve our goal, thorough research of all the criteria that would need to be considered when drafting a QB would need to be analyzed. This process led us to nine top level criteria: 1 1. Strength of college experience: Just how valuable was the players experience at this level to his future success? • Sub Criteria: College (big/small), college winning percentage, college years started. -

Master 2009.Indd

Louisiana football... coaching staff Rickey Bustle Louisiana head coach Rickey Bustle has guided the Cajuns for seven seasons and enters his eighth year in Cajun Country in 2009. The Bustle File Bustle’s Cajuns have won six games in three of the past four seasons, a stretch not equaled since UL was a member of the Big West Conference from 1993-95. In fact, since the 2005 season, only three Sun Belt schools can boast three six-win seasons. Coach Bustle was victorious 23 times in his first five seasons with the Cajuns Head Coach from 2002-06, including 11 of the last 17 games. UL won only nine games in the five seasons prior to Bustle’s arrival from 1997-2001. Clemson, ‘76 Bustle saw his winning percentage increase each of the first four seasons since Eighth Season taking the job in 2002, but regressed to .500 in 2006. His 6-6 record in 2006 was only deemed a regression because of the high standards and raised levels of Personal expectations by the Cajuns and their fans. In fact, Bustle’s 12 wins from 2005-06 Born: August 23, 1953 were the most in a two-year period since 1994-95. One of Bustle’s proudest moments was watching four-time All-Sun Belt Hometown: Summerville, S.C. selection and 2008 SBC Player of the Year, Tyrell Fenroy, become just the seventh Wife: Lynn player in NCAA history to rush for 1,000 yards in four consecutive seasons. Son: Brad Under Bustle, the Cajuns have been .500 or better at home in six of his seven seasons. -

Izfs4uwufiepfcgbigqm.Pdf

PANTHERS 2018 SCHEDULE PRESEASON Thursday, Aug. 9 • 7:00 pm Friday, Aug. 24 • 7:30 pm (Panthers TV) (Panthers TV) GAME 1 at BUFFALO BILLS GAME 3 vs NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS Friday, Aug. 17 • 7:30 pm Thursday, Aug. 30 • 7:30 pm (Panthers TV) (Panthers TV) & COACHES GAME 2 vs MIAMI DOLPHINS GAME 4 at PITTSBURGH STEELERS ADMINISTRATION VETERANS REGULAR SEASON Sunday, Sept. 9 • 4:25 pm (FOX) Thursday, Nov. 8 • 8:20 pm (FOX/NFLN) WEEK 1 vs DALLAS COWBOYS at PITTSBURGH STEELERS WEEK 10 ROOKIES Sunday, Sept. 16 • 1:00 pm (FOX) Sunday, Nov. 18 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 2 at ATLANTA FALCONS at DETROIT LIONS WEEK 11 Sunday, Sept. 23 • 1:00 pm (CBS) Sunday, Nov. 25 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 3 vs CINCINNATI BENGALS vs SEATTLE SEAHAWKS WEEK 12 2017 IN REVIEW Sunday, Sept. 30 Sunday, Dec. 2 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 4 BYE at TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS WEEK 13 Sunday, Oct. 7 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Sunday, Dec. 9 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 5 vs NEW YORK GIANTS at CLEVELAND BROWNS WEEK 14 RECORDS Sunday, Oct. 14 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Monday, Dec. 17 • 8:15 pm (ESPN) WEEK 6 at WASHINGTON REDSKINS vs NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEK 15 Sunday, Oct. 21 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) Sunday, Dec. 23 • 1:00 pm (FOX) WEEK 7 at PHILADELPHIA EAGLES vs ATLANTA FALCONS WEEK 16 TEAM HISTORY Sunday, Oct. 28 • 1:00 pm* (CBS) Sunday, Dec. 30 • 1:00 pm* (FOX) WEEK 8 vs BALTIMORE RAVENS at NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEK 17 Sunday, Nov. -

RAIDERS 49Ers Alumni Program FOX | 10:00 A.M

2018 alumni magazine 2018 ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS Schedule 4 Letter from the GM 5 Remembering our 49ers Hall of Famers 6 49ers Who Have Passed 10 Tuesdays With Dwight 12 Where Are They Now? 18 Alumni Memories 22 Alumni Assistance Programs 24 Cedrick Hardman: 26 The Hard Working Man Terrell Owens – Induction to The 32 Pro Football Hall of Fame 1968 - 50th Anniversary 36 The Edward J. DeBartolo Sr. 37 49ers Hall of Fame Other Halls of Fame 40 2017 Team Awards 41 Finance to Football: 44 The Robert Saleh Story The 2018 Coaching Staff 49 The 2018 Draft 50 49ERS ALUMNI 2018 SCHEDULE CONTACT INFO If you have any questions, comments, updates, address changes or know of fellow 49ers Alumni that would like WEEK 1 | SEPT. 9 WEEK 9 | NOV. 1 to find out more about the at VIKINGS vs RAIDERS 49ers Alumni program FOX | 10:00 A.M. FOX/NFLN | 5:20 P.M. or to receive the Alumni Magazine, please contact Guy McIntyre or Carri Wills. WEEK 2 | SEPT. 16 WEEK 10 | NOV. 12 vs LIONS vs GIANTS Guy McIntyre FOX | 1:05 P.M. ESPN | 5:15 P.M. Director of Alumni Relations Phone: 408.986.4834 Email: [email protected] WEEK 3 | SEPT. 23 WEEK 12 | NOV. 25 at CHIEFS at BUCCANEERS Carri Wills FOX | 10:00 A.M. FOX | 10:00 A.M. Alumni Relations Assistant Phone: 408.986.4808 Email: [email protected] WEEK 4 | SEPT. 30 WEEK 13 | DEC. 2 at CHARGERS at SEAHAWKS Alumni coordinators CBS | 1:25 P.M. -

Washington Redskins at New York Giants October 28, 2018 | East Rutherford, Nj Game Release

WEEK 8 WASHINGTON REDSKINS AT NEW YORK GIANTS OCTOBER 28, 2018 | EAST RUTHERFORD, NJ GAME RELEASE 21300 Redskin Park Drive | Ashburn, VA 20147 | 703.726.7000 @Redskins | www.Redskins.com REGULAR SEASON - WEEK 8 WASHINGTON REDSKINS (4-2) AT NEW YORK GIANTS (1-6) Sunday, Oct. 28 | 1:00 p.m. ET MetLife Stadium (82,500) | East Rutherford, N.J. REDSKINS TRAVEL TO GIANTS GAME CENTER FOR DIVISION CONTEST SERIES HISTORY: Redskins trail all-time series, 68-100-4 Following back-to-back wins at FedExField, the Washington Red- Redskins trail regular season series, 67-99-4 skins will look to remain atop the NFC East when they travel to face the Last meeting: Dec. 31, 2017 (18-10, NYG) New York Giants. Kickoff at MetLife Stadium is scheduled for 1 p.m. ET. The Redskins hold a one-and-a-half game lead over the Philadel- TELEVISION: FOX phia Eagles and Dallas Cowboys and are 4-1 against teams in the NFC. Kenny Albert (play-by-play) With the win over their rival Cowboys last week, the Redskins Charles Davis (color) opened division play with a victory for the fi rst time since 2011 and a Pam Oliver (sideline) win over the NY Giants will give them their fi rst 2-0 start in the division since 2010. The Redskins are coming off one of their best defensive RADIO: Redskins Radio Network performances of the season and have been one of the league's topics Larry Michael (play-by-play) of discussion following their performance against Dallas. Head Coach Jay Gruden was asked about the defensive improve- Chris Cooley (analysis) ments from last year during his Monday afternoon podium session. -

How Sotomayor Restrained College Athletes Phillip J

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2016 The oJ cks and the Justice: How Sotomayor Restrained College Athletes Phillip J. Closius University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Phillip J. Closius, The Jocks and the Justice: How Sotomayor Restrained College Athletes, 26 Marquette Sports Law Review 493 (2016). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/989 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOCKS AND THE JUSTICE: HOW SOTOMAYOR RESTRAINED COLLEGE ATHLETES PHILLIP J. CLOSIUS* I. INTRODUCTION Two judicial opinions have shaped the modem college athletic world.' NCAA v. Board ofRegents ofthe University ofOklahoma2 declared the NCAA's exclusive control over the media rights to college football violated the Sherman Act.' That decision allowed universities and conferences to control their own media revenue and laid the foundation for the explosion of coverage and income in college football today.' Clarett v. NFL held that the provision then in the National Football League's (NFL) Constitution and By-Laws that prohibited players from being eligible for the NFL draft until three years from the date of their high school graduation was immune from Sherman Act liability because it was protected by the non-statutory labor law exemption.' An earlier decision, Haywood v. -

17 08 Tradition.Indd

1954 BRUINS-NATIONAL CHAMPIONS BBRUINRUIN FFOOTBALLOOTBALL TTRADITIONRADITION 11954954 BRUINSBRUINS - NATIONALNATIONAL CHAMPIONSCHAMPIONS Fifty-four years ago, UCLA fi elded the fi nest football team in the school’s fi nal 15 minutes to fi nish the season with a perfect 9-0 record. history. The 1954 Bruins compiled a perfect 9-0 record and were voted National UCLA did not play in the Rose Bowl following that magical season because of the & STAFFCOACHES 2008 BRUINS Champions by United Press International at the end of the season. “no-repeat” rule. It was voted No. 1 on the United Press International poll and shared Most of the key players from the 1953 Bruins, who were 8-2, re- the national championship with Ohio State (the Associated Press champ). turned in 1954, led by legendary head coach Henry R. “Red” Sand- The 1954 team set numerous records, including points in a season (367), points ers. During his nine seasons in Westwood, Sanders’ winning per- in a game (72) and touchdowns in a season (55). It led the nation in scoring offense centage was .773 and he won three Pacifi c Coast Conference titles. (40.8 average) and scoring defense (4.4 average). Today, it still ranks No. 1 in school The Bruins opened the 1954 season on Sept. 18 with a 67-0 victory over San Diego history in rushing defense (659 yards), total defense (1,708 yards) and scoring defense Navy at the Coliseum. The point total was the highest in school history at the time. The (40 points) while its 40.8 scoring average ranks second in school history. -

Jonathan Vilma Analyst, Fox Nfl

JONATHAN VILMA ANALYST, FOX NFL Super Bowl champion and three-time Pro Bowler Jonathan Vilma joins FOX Sports in 2020 as an NFL game analyst alongside play-by-play announcer Kenny Albert and reporter Shannon Spake. A 10-year veteran NFL linebacker, BCS national champion and prominent college football studio analyst the past several years, Vilma makes his NFL analyst debut on Sundays this fall. Prior to FOX Sports, Vilma spent four years at ABC and ESPN, serving as a color commentator for ABC’s college pregame, halftime and postgame shows in 2018 and 2019, and as an ESPN college football analyst beginning in 2016. Vilma also regularly appeared on several ESPN programs, including “Get Up” and “First Take,” in addition to time at NBC and NBCSN as a pregame and halftime analyst covering Notre Dame football in 2015. He was selected out of the University of Miami by the New York Jets as the 12th pick in the first round of the 2004 NFL Draft. After being named the 2004 NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year by the Associated Press, Vilma went on to lead the league in tackles (173) in 2005 and was named to his first Pro Bowl on the strength of 128 solo tackles, six passes defensed, four forced fumbles and one interception. After suffering a season-ending knee injury in Week 7 of the 2007 season, the defensive leader was traded to the New Orleans Saints in February 2008. The New Orleans partnership was a fruitful one, with Vilma serving as a defensive captain in the Saints’ run to the Super Bowl XLIV title in 2009, a season in which he led the club in tackles (110) with two sacks and three interceptions. -

All-Time Award Winners Mules’ First-Team All-America Selections

All-Time Award Winners Mules’ First-Team All-America Selections Cannon Coleman Czerniewski Grace Green Grimes Hebert Mules’ First-Team All-Americans Name ................... Pos. Year Jim Urczyk . OT 1968 Steve Huff . PK 1985 Phil Grimes . DE 1986 Jeff Wright . NG 1987 Mark Peoples . FS 1988 Bart Woods . DE 1992 Bart Woods . DE 1993 Huff Meyer Peoples Ricketts Taylor Shane Meyer . PK 1997 Colston Weatherington . DE 1999 Kegan Coleman . RB 2003 Roderick Green . DE 2003 Darryl Grace . OL 2005 Kendall Ricketts . FS 2006 Kendall Ricketts . FS 2007 Eric Czerniewski . QB 2010 Jamorris Warren . WR 2010 David Cannon . TE 2011 LaVance Taylor . RB 2014 Urczyk Warren Weatherington Woods Wright Seth Hebert . TE 2017 2003 Darryl Grace, OL 1998 Shane Meyer, PK 1st Team Mules in the 2006 Jeff Phillips (1985-88) 2005 Darryl Grace, OL; Matt 2000 Clint Steiner, DB 1st Team 2007 2001 Team, William Green Frankel,P; Jon Books, OL Matt Gigliotti, OL 3rd Team UCM Hall of Fame (1964-67) 2006 Matt Frankel, P Tim Urich, DL 3rd Team 1992 Vernon Kennedy (1926-29) 2008 2002 Team, Eddie Coates 2007 Matt Frankel, P; Jon Books, OL 2001 Rusty Miller, DL 2nd Team Clarence Whiteman (1923-26) (1968-70), 2008 Adrian Singletary, LB 2002 Tim Urich, DL 1st Team Tad C. Reid (coach, 1924-34) Kevin Nickerson (1998-2001), 2010 Eric Czerniewski, QB; Logan Nate Thomas, WR 2nd Team 1926 Team (7-0-1, Al Molde (coach, 1980-82) Freeman OL Aaron Urich, DL 3rd Team MIAA Champions) 2009 Shane Meyer (1995-98) 2005 Darryl Grace, OL 2nd Team 1993 Lee S. -

2016 Nfl Draft Facts & Figures

Minnesota Vikings 2016 Draft Guide MINNESOTA VIKINGS PRESEASON WEEK DAY DATE OPPONENT TIME (CT) TV RADIO P1 Friday Aug. 12 at Cincinnati Bengals 6:30 p.m. FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK P2 Thursday Aug. 18 at Seattle Seahawks 9:00 p.m. FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK P3 Sunday Aug. 28 San Diego Chargers Noon FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK P4 Thursday Sept. 1 Los Angeles Rams 7:00 p.m. FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK REGULAR SEASON WEEK DAY DATE OPPONENT TIME (CT) TV RADIO 1 Sunday Sept. 11 at Tennessee Titans Noon FOX KFAN / KTLK 2 Sunday Sept. 18 Green Bay Packers 7:30 p.m. NBC KFAN / KTLK 3 Sunday Sept. 25 at Carolina Panthers Noon FOX KFAN / KTLK 4 Monday Oct. 3 New York Giants 7:30 p.m. ESPN KFAN / KTLK 5 Sunday Oct. 9 Houston Texans Noon CBS KFAN / KTLK 6 Sunday Oct. 16 BYE WEEK 7 Sunday Oct. 23 at Philadelphia Eagles Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 8 Monday Oct. 31 at Chicago Bears 7:30 p.m. ESPN KFAN / KTLK 9 Sunday Nov. 6 Detroit Lions Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 10 Sunday Nov. 13 at Washington Redskins Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 11 Sunday Nov. 20 Arizona Cardinals Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 12 Thursday Nov. 24 at Detroit Lions 11:30 a.m. CBS KFAN / KTLK 13 Thursday Dec. 1 Dallas Cowboys 7:25 p.m. NBC/NFLN KFAN / KTLK 14 Sunday Dec. 11 at Jacksonville Jaguars Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 15 Sunday Dec. 18 Indianapolis Colts Noon* CBS KFAN / KTLK 16 Saturday Dec. 24 at Green Bay Packers Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 17 Sunday Jan. -

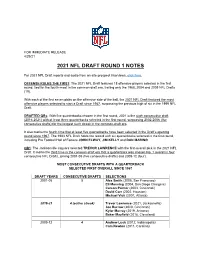

2021 Nfl Draft Round 1 Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/29/21 2021 NFL DRAFT ROUND 1 NOTES For 2021 NFL Draft reports and audio from on-site prospect interviews, click here. OFFENSE RULES THE FIRST: The 2021 NFL Draft featured 18 offensive players selected in the first round, tied for the fourth-most in the common-draft era, trailing only the 1968, 2004 and 2009 NFL Drafts (19). With each of the first seven picks on the offensive side of the ball, the 2021 NFL Draft featured the most offensive players selected to start a Draft since 1967, surpassing the previous high of six in the 1999 NFL Draft. DRAFTED QBs: With five quarterbacks chosen in the first round, 2021 is the sixth consecutive draft (2016-2021) with at least three quarterbacks selected in the first round, surpassing 2002-2006 (five consecutive drafts) for the longest such streak in the common-draft era. It also marks the fourth time that at least five quarterbacks have been selected in the Draft’s opening round since 1967. The 1983 NFL Draft holds the record with six quarterbacks selected in the first round, including Pro Football Hall of Famers JOHN ELWAY, JIM KELLY and DAN MARINO. QB1: The Jacksonville Jaguars selected TREVOR LAWRENCE with the first-overall pick in the 2021 NFL Draft. It marks the third time in the common-draft era that a quarterback was chosen No. 1 overall in four consecutive NFL Drafts, joining 2001-05 (five consecutive drafts) and 2009-12 (four). MOST CONSECUTIVE DRAFTS WITH A QUARTERBACK SELECTED FIRST OVERALL SINCE 1967 DRAFT YEARS CONSECUTIVE DRAFTS SELECTIONS 2001-05 5 Alex Smith (2005, San Francisco) Eli Manning (2004, San Diego Chargers) Carson Palmer (2003, Cincinnati) David Carr (2002, Houston) Michael Vick (2001, Atlanta) 2018-21 4 (active streak) Trevor Lawrence (2021, Jacksonville) Joe Burrow (2020, Cincinnati) Kyler Murray (2019, Arizona) Baker Mayfield (2018, Cleveland) 2009-12 4 Andrew Luck (2012, Indianapolis) Cam Newton (2011, Carolina) Sam Bradford (2010, St.