Haydn: the Libretto of "The Creation", New Sources and a Possible Librettist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Stanley a Miracle of Art and Nature

John Stanley, “A Miracle of Art and Nature”: The Role of Disability in the Life and Career of a Blind Eighteenth-Century Musician by John Richard Prescott Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor James Davies Professor Susan Schweik Fall 2011 Abstract John Stanley, “A Miracle of Art and Nature”: The Role of Disability in the Life and Career of a Blind Eighteenth-Century Musician by John Richard Prescott Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair This dissertation explores the life and career of John Stanley, an eighteenth-century blind organist, composer, conductor and impresario. Most historians of blindness discuss Stanley but merely repeat biographical material without adding any particular insights relating to his blindness. As for twentieth-century musicologists, they have largely ignored Stanley’s blindness. The conclusion is that Stanley’s blindness, despite being present in most of his reception, is not treated as a defining factor. This study pursues new questions about Stanley’s blindness. His disability is given pride of place, and perspectives from the fields of disability studies and minority studies are central to the work. A biographical sketch precedes a discussion of the role of Stanley’s blindness in his reception. The central role of Stanley’s amanuensis and sister-in-law, Anne Arlond, leads to a discussion of issues of gender, and the general invisibility of caregivers. Chapter 2 explores those aspects of Stanley’s life that required an engagement with literate music. -

293 BIBLIOGRAPHY Abrams, M. H. the Mirror and the Lamp. New

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abrams, M. H. The Mirror and the Lamp. New York: W. W. Norton, 1953. Adams, Joseph. Memoirs of the Life and Doctrines of the Late John Hunter, Esq. 2 ed. London: Callow and Hunter, 1818. Alexander, David. “Kauffman and the Print Market in Eighteenth-Century England.” In Angelica Kauffman: A Continental Artist in Georgian England, edited by Wendy Wassyng Roworth. London: Reaktion Books, 1992. Ariès, Philippe. The Hour of Our Death. Translated by Helen Weaver. 1st American ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981. Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics, and Politics. London and New York: Routledge, 1993. Armstrong, Nancy. Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. Badura-Skoda, Eva. “Aspects of Performance Practice.” In Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music, edited by Robert Marshall. New York: Schirmer, 1994. Balderston, Katharine, ed. Thraliana: The Diary of Mrs. Hester Lynch Thrale, Later Mrs. Piozzi. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1942. Barker, Hannah, and Elaine Chalus, eds. Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities. London: Longman, 1997. Beci, Veronika. Musikalische Salons: Blütezeit einer Frauenkultur. Düsseldorf: Artemis and Winkler, 2000. Bender, John, and David Wellbery, eds. Chronotypes: The Construction of Time. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991. Bermingham, Ann. Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000. 293 294 Bettany, G. T. “Hunter, John.” In The Dictionary of National Biography, 287-93. London: Oxford University Press, 1917. Bindman, David. Hogarth and His Times: Serious Comedy. London: British Museum Press, 1997. Blake, William. -

The Fall of Egypt by John Stanley (1712-1786)

THE FALL OF EGYPT BY JOHN STANLEY (1712-1786) IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I THOMAS DEWEY MA BY RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF YORK MUSIC APRIL 2016 2 3 ABSTRACT This is an edition of John Stanley's oratorio The Fall of Egypt with critical commentary as well as detailed writing on its history, libretto, context and word setting. John Stanley (1712-1786) composed it for performance in 1774 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. It received two performances that year and then one in 1775. It appears to have lain unedited and unperformed since, surviving in a sole manuscript in the library of the Royal College of Music. As Stanley was blind, this manuscript was copied by amanuenses; it bears the recognizable handwriting of some of his known copyists. It is scored for a full Baroque orchestra with trumpets, horns and timpani. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................... 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... 4 TABLES ................................................................................................................................ 5 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION ........................................................................................... 6 THE SOURCES .................................................................................................................... 7 ORATORIO AND THE ORATORIO SEASON ............................................................. -

From Handel's Death to the Handel Commemoration: the Lenten

From Handel’s Death to the Handel Commemoration: The Lenten Oratorio Series at the London Theatres from 1760 to 1784 EVA ZÖLLNER The history of English oratorio during the late eighteenth centu- ry is often summed up as a mere post-Handelian period, the only event worth noting during this time being the famous Handel Commemora- tion, held in Westminster Abbey in 1784. Yet the Commemoration, notable for its performances of Handel’s oratorios with massive vocal and orchestral forces, was not an isolated event. In fact there was a strong performance tradition of oratorios in London even before the Commemoration, reaching back to Handel’s own lifetime. In the last decades of his life, Handel had established an annual series of oratorio performances at London’s Covent Garden Theatre during Lent: starting off with occasional performances at the King’s Theatre, Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Covent Garden in the mid-1730s, by the 1750s these performances had developed into a regular series, with Covent Garden as the main venue. On the Wednesdays and Fridays du- ring Lent, audiences could expect a series of oratorio performances, usually commencing on the irst Friday in Lent and ending on the Fri- day before Holy Week, a full-length oratorio series usually consisting of eleven performances. This pattern had not originally been planned as such, but had gradually evolved over a longer period of time. Handel’s own oratorio performances in the London theatres were not as a rule conined to the Lenten period,1 but eventually, as Winton Dean puts it, “gravitated towards it”.2 Surprisingly enough, this performance tradition was carried on by Handel’s successors without even a break: His own series at Cov- ent Garden was carried on after his death by John Christopher Smith (1712–1795) and John Stanley (1712–1786). -

35 Chapter II. Public and Private

Chapter II. Public and Private “Moral Sentiment” and “Physical Truth”: the Upstairs and Downstairs of Anne and John Hunter What, besides a couple of inches of newsprint, might have connected the worlds of Anne and John Hunter? Anne Hunter’s poems, set by Haydn as canzonets, and John Hunter’s work and reputation do not immediately suggest themselves to be kindred. Admittedly, Hunterian biographies, which are considerably unified in their treatment of the couple, strongly tend to suggest that neither spouse was influential in the pursuits of the other. The British Critic set the tone in 1802: “Such a union of science and genius has seldom been contemplated by the world, as in the persons of John Hunter and his lady,” wrote an anonymous reviewer. “The former, investigating physical truth with a zeal and acuteness not often equaled; the latter, adorning moral sentiment with the finest graces of language.”1 Throughout the Hunterian biographical literature of the next two centuries, husband and wife are made to represent an ideal juxtaposition, playing opposite, though complementary, roles.2 John Hunter, who held the title Surgeon Extraordinary to George III, earned distinction for his significant contributions to medical knowledge, especially in the areas of gunshot wounds, venereal disease, and aneurysm. In order to investigate “physical truth” he assembled an extensive collection of 1 Robert Nares, “Art. 12. Poems. By Mrs. John Hunter,” The British Critic 20 (1802). 2 The earliest book-length biography, written by Jessé Foot just one year after Hunter’s death, provides the main exception. Foot’s dislike for the surgeon appears to have strongly influenced his retelling of his subject’s life; however, the document is nevertheless valuable as an antidote to the Hunterian mythologizing that gathered enormous momentum in subsequent decades. -

John Christopher Smiths Paradise Lost Nach Milton Epische Dramatik, Dramatische Poesie Und Das Problem Ihrer Vertonung

Marie-Agnes Dittrich John Christopher Smiths Paradise Lost nach Milton Epische Dramatik, dramatische Poesie und das Problem ihrer Vertonung In einer Musikgeschichtsschreibung, die, wie einmal gesagt wurde, Komponisten in Großmeister, Kleinmeister und Zwerge einteilt, fiele John Christopher Smith d.J. mit Sicherheit nicht in die erste Kategorie. Heute kennt man ihn nur noch als Bewahrer der Händel-Tradition. Trotzdem möchte ich mich mit Smith als Komponisten be- fassen, noch dazu mit seinem Oratorium Paradise Lost (vollendet 1758), das auf Miltons Epos basiert, obwohl schon Smitbs Stiefsohn William Coxe, sein Biograph, es für sein uninteressantestes und mißlungenstes Werk hielt.' Aber trotzdem wirft dieses Stück interessante Fragen auf, besonders hinsichtlich seiner Dramatik, die zwar, ständig wird es wiederholt, zum Wesen der Gattung des Oratoriums gehöre, wenn auch nicht zu verkennen ist, daß ausgerechnet einige der berühmtesten Oratorien als die Ausnahmen von dieser Regel gelten. 2 Außerdem wird häufig nicht definiert, was genau man eigentlich meint, wenn man im Zusammenhang mit dem Oratorium von «Dramatik» spricht. Oft drängt sich der Eindruck auf, gerade in neuerer Literatur sei einfach «spannend» gemeint.3 Das Problem des Dramatischen möchte ich unter zwei Aspekten betrachten. Erstens soll es um das Problem der Dramatisierbarkeit eines großen epischen Stoffes gehen; zweitens um die spezifische Dramatik in Miltons Poesie und das Problem ihrer Vertonung. Ich komme zum ersten Punkt, dem großen Stoff. Smiths Librettist war Benjamin Stillingfleet, ein Gelehrter und intimer Kenner der klassischen großen Epen und Milton- Herausgeber (und nebenbei derjenige, der zu seinen literarischen Gesprächen mit gebildeten Damen die berühmt gewordenen blauen Strümpfe trug). Stillingfleet war sich natürlich bewußt, daß die Besonderheiten, die Miltons Epos auszeichnen, ebendie sind, die es für eine Vertonung so ungeeignet wie möglich machen. -

The First Fleet Piano: Volume

THE FIRST FLEET PIANO A Musician’s View Volume One THE FIRST FLEET PIANO A Musician’s View Volume One GEOFFREY LANCASTER Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Lancaster, Geoffrey, 1954-, author. Title: The first fleet piano : a musician’s view. Volume 1 / Geoffrey Richard Lancaster. ISBN: 9781922144645 (paperback) 9781922144652 (ebook) Subjects: Piano--Australia--History. Music, Influence of--Australia--History. Music--Social aspects--Australia. Music, Influence of. Dewey Number: 786.20994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover based on an original design by Gosia Wlodarczak. Cover design by Nic Welbourn. Layout by ANU Press. Printed by Griffin Press. This edition © 2015 ANU Press. Contents List of Plates . xv Foreword . xxvii Acknowledgments . xxix Descriptive Conventions . xxxv The Term ‘Piano’ . xxxv Note Names . xxxviii Textual Conventions . xxxviii Online References . xxxviii Introduction . 1 Discovery . 1 Investigation . 11 Chapter 1 . 17 The First Piano to be Brought to Australia . 22 The Piano in London . 23 The First Pianos in London . 23 Samuel Crisp’s Piano, Made by Father Wood . 27 Fulke Greville Purchases Samuel Crisp’s Piano . 29 Rutgerus Plenius Copies Fulke Greville’s Piano . 31 William Mason’s Piano, Made by Friedrich Neubauer(?) . 33 Georg Friedrich Händel Plays a Piano . -

John Stanley a Miracle of Art and Nature

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title John Stanley, "A Miracle of Art and Nature": The Role of Disability in the Life and Career of a Blind Eighteenth-Century Musician Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6cn0h2r2 Author Prescott, John Richard Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Stanley, “A Miracle of Art and Nature”: The Role of Disability in the Life and Career of a Blind Eighteenth-Century Musician by John Richard Prescott Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor James Davies Professor Susan Schweik Fall 2011 Abstract John Stanley, “A Miracle of Art and Nature”: The Role of Disability in the Life and Career of a Blind Eighteenth-Century Musician by John Richard Prescott Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair This dissertation explores the life and career of John Stanley, an eighteenth-century blind organist, composer, conductor and impresario. Most historians of blindness discuss Stanley but merely repeat biographical material without adding any particular insights relating to his blindness. As for twentieth-century musicologists, they have largely ignored Stanley’s blindness. The conclusion is that Stanley’s blindness, despite being present in most of his reception, is not treated as a defining factor. This study pursues new questions about Stanley’s blindness. His disability is given pride of place, and perspectives from the fields of disability studies and minority studies are central to the work. -

How Henry Carey Reinvented English Music and Song Jennifer Cable University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Faculty Publications Music 2008 Leadership through Laughter: How Henry Carey Reinvented English Music and Song Jennifer Cable University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/music-faculty-publications Part of the Leadership Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Cable, Jennifer. "Leadership through Music and Laughter: How Henry Carey Reinvented English Music and Song." In Leadership at the Crossroads, edited by Joanne B. Ciulla, Crystal L. Hoyt, George R. Goethals, Donelson R. Forsyth, Michael A. Genovese, and Lori Cox. Han, 172-185. Westport, CT: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2008. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 Leadership through Music and Laughter: How Henry Carey Reinvented English Music and Song JENNIFER CABLE Of all the Toasts, that Brittain boasts; tire Gim, the Gent, the folly, the Brown, the Fair, the Debonnair, there's none cry'd up like Polly; She's c/zarm'd t/1e Town, has quite rnt down the Opera of Rolli: Go where you will, tile subject still, is pretty, pretty Polly. Polly refers to Miss Polly Peachum, a character in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera of 1728 Qanuary). Henry Carey (1687-1743) set this verse (1728) to his famous tune Sally in our Alley, which Gay had used in the opera. -

Handel, His Contemporaries and Early English Oratorio Händel, Njegovi Sodobniki in Zgodnji Angleški Oratorij

M. GARDNER • HANDEL, HIS CONTEMPORARIES ... UDK 784.5Handel Matthew Gardner Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Univerza v Heidelbergu Handel, His Contemporaries and Early English Oratorio Händel, njegovi sodobniki in zgodnji angleški oratorij Prejeto: 4. februar 2012 Received: 4th February 2012 Sprejeto: 15. marec 2012 Accepted: 15th March 2012 Ključne besede: Händel, Greene, Boyce, Apollo Keywords: Handel, Greene, Boyce, Apollo Acad- Academy, angleški oratorij emy, English Oratorio Iz v l e č e k Ab s t r a c t Pregled razvoja angleškega oratorija od prvih Surveys the development of English oratorio from javnih uprizoritev Händlovega oratorija Esther the first public performances of Handel’s Esther (1732) do 1740. Obravnava vpliv Händla na nje- (1732) until c. 1740. Handel’s influence over his gove angleške sodobnike glede na slog, obliko, English contemporaries is discussed referring to izbiro teme in alegorično vsebino, ter prikaže bolj style, formal design, subject choice and allegorical celovito podobo angleškega oratorija v 30. letih 18. content, providing a more complete than hitherto stoletja kot kdaj koli doslej. picture of the genre in the 1730s. When Handel gave the first public performance of an English oratorio with Esther in 1732, he was introducing London audiences to a new form of theatrical entertain- ment that would eventually become the staple of his London theatre seasons.1 The first ‘public’ performances of Esther took place at the Crown and Anchor Tavern at the end of February and beginning of March 1732 and were well received; several weeks later, on 2 May, it was performed in the theatre with additions taken from various earlier works including the Coronation Anthems (1727) and with a new opening scene.2 The 1 This article was originally presented as a conference paper under the title ‘Esther and Handel’s English Contemporaries’ at the American Handel Society conference in Seattle, March 2011; it appears here in a revised version. -

4996737-Ac2c4b-635212045725.Pdf

7501 CO_Whereer you walk_BOOKLET_FINAL.indd 1 19/02/2016 10:28 ‘WHERE’ER YOU WALK’ HANDEL’S FAVOURITE TENOR Recorded at All Saints Church Tooting, London, UK from 15 to 18 September 2015 A programme of music composed for or sung by Produced and engineered by Andrew Mellor Assistant engineer: Claire Hay John Beard (c.1715-1791) Photography: Benjamin Ealovega, Simon Wall (inside cover) Harpsichord technicians: Keith McGowan, Malcolm Greenhalgh, Nicholas Parle and Oliver Sandig ALLAN CLAYTON tenor Orchestra playing on period instruments at A = 415 Hz MARY BEVAN soprano (track 10) We are extremely grateful to George and Efthalia Koukis for making this recording possible. THE CHOIR OF CLASSICAL OPERA (tracks 8 &14) We are also grateful to the following people for their generous support: Sir Vernon and Lady Ellis, Mark and Liza THE ORCHESTRA OF CLASSICAL OPERA Loveday, Kate Bingham and Jesse Norman, Pierce and Beaujolais Rood, Ann Bulford and David Smith, Mark and Matthew Truscott (leader) Jill Pellew, The Sainer Charity, P C A Butterworth, Jack and Alma Gill, James Dooley, Tom Joyce and Annette Atkins, James Eastaway (oboe solo, tracks 1 & 10) Dyrk and Margaret Riddell, Marilyn Stock, and all the other individuals who supported this proJect. Philip Turbett (bassoon solo, tracks 10 & 13 -14) Special thanks to: TallWall Media, Rachel Chaplin, Adrian Horsewood, Neil Jenkins and David Vickers IAN PAGE conductor 2 WHERE’ER YOU WALK / ALLAN CLAYTON WHERE’ER YOU WALK / ALLAN CLAYTON 3 7501 CO_Whereer you walk_BOOKLET_FINAL.indd 2-3 19/02/2016 10:28 -

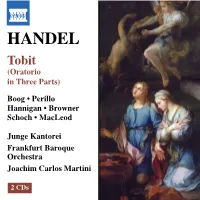

HANDEL Tobit (Oratorio in Three Parts)

570113-14bk Handel US 12/12/06 3:49 pm Page 16 HANDEL Tobit (Oratorio in Three Parts) Boog • Perillo Hannigan • Browner Schoch • MacLeod Junge Kantorei Frankfurt Baroque Orchestra Joachim Carlos Martini 2 CDs 8.570113-14 16 570113-14bk Handel US 12/12/06 3:49 pm Page 2 George Frideric CD 2 Part 2 (cont.) HANDEL 1 Air: Thou, God most high, and Thou alone (Azarias) ( Air: My Son, how happy in this thy Sweet Return (1685-1759) Belshazzar: Thou, God most high, and Thou alone (Anna) Rodalinda: Mio caro bene 2 Duet: Cease thy Anguish, Smile once more ) Chorus: Let none Despair (Israelites) (Azarias & Tobias) Hercules: Let none despair Tobit Athalia: Cease thy anguish, smile once more ¡ Accompagnato: Blest be the God of Heav’n 3 Chorus: The Clouded Scene begins to clear (Tobit & Raguel) J.C. Smith An Oratorio in Three Parts compiled by (Israelites) ™ Air: May true Joy and every blessing (Raguel) John Christopher Smith (1712-1795) Athalia: The clouded scene begins to clear Giulio Cesare in Egitto: Dal fulgor di questa spada 4 Sinfonia: Alceste: Larghetto (JCM) £ Terzetto: More chearfull appearing Libretto by Thomas Morell Symphony: Jephtha: Symphony (JCM) (Anna, Tobias & Sarah) 5 Recitative: How happy, Daughter (Raguel & Sarah) Orlando: Consolati, o bella J.C. Smith ¢ Air: Watchful angels, let me share (Sarah) 6 Air: To nobler Joys aspiring (Sarah) Esther: Watchful angels Anna . Maya Boog, Soprano Alessandro: L’amor, che per te sento ∞ Recitative: O King of Kings (Sarah) Sarah . Linda Perillo, Soprano 7 Recitative: O Azarias, I must freely own Esther: O King of Kings (JCM) (Tobias & Azarias) J.C.