Challenges and Opportunities for Hydrography in the New Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Water Levels and Flow

253 CHAPTER 5 WATER LEVELS AND FLOW 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this chapter is to provide the hydrographer and technical reader the fundamental information required to understand and apply water levels, derived water level products and datums, and water currents to carry out field operations in support of hydrographic surveying and mapping activities. The hydrographer is concerned not only with the elevation of the sea surface, which is affected significantly by tides, but also with the elevation of lake and river surfaces, where tidal phenomena may have little effect. The term ‘tide’ is traditionally accepted and widely used by hydrographers in connection with the instrumentation used to measure the elevation of the water surface, though the term ‘water level’ would be more technically correct. The term ‘current’ similarly is accepted in many areas in connection with tidal currents; however water currents are greatly affected by much more than the tide producing forces. The term ‘flow’ is often used instead of currents. Tidal forces play such a significant role in completing most hydrographic surveys that tide producing forces and fundamental tidal variations are only described in general with appropriate technical references in this chapter. It is important for the hydrographer to understand why tide, water level and water current characteristics vary both over time and spatially so that they are taken fully into account for survey planning and operations which will lead to successful production of accurate surveys and charts. Because procedures and approaches to measuring and applying water levels, tides and currents vary depending upon the country, this chapter covers general principles using documented examples as appropriate for illustration. -

National Hydrography Data Content Standard for Coastal and Inland Waterways Public Review Draft, January 2000

FGDC Data Committee FGDC Document Number National Hydrography Data Content Standard for Coastal and Inland Waterways Public Review Draft, January 2000 NSDI National Spatial Data Infrastructure National Hydrography Data Content Standard for Coastal and Inland Waterways – Public Review Draft Bathymetric Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee January 2000 Federal Geographic Data Committee i FGDC Data Committee FGDC Document Number National Hydrography Data Content Standard for Coastal and Inland Waterways Public Review Draft, January 2000 Established by Office of Management and Budget Circular A-16, the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) promotes the coordinated development, use, sharing, and dissemination of geographic data. The FGDC is composed of representatives from the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Energy, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior, State, and Transportation; the Environmental Protection Agency; the Federal Emergency Management Agency; the Library of Congress; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; the National Archives and Records Administration; and the Tennessee Valley Authority. Additional Federal agencies participate on FGDC subcommittees and working groups. The Department of the Interior chairs the committee. FGDC subcommittees work on issues related to data categories coordinated under the circular. Subcommittees establish and implement standards for data content, quality, and transfer; encourage the exchange of information and the transfer of data; and organize the -

Modeling Groundwater Rise Caused by Sea-Level Rise in Coastal New Hampshire Jayne F

Journal of Coastal Research 35 1 143–157 Coconut Creek, Florida January 2019 Modeling Groundwater Rise Caused by Sea-Level Rise in Coastal New Hampshire Jayne F. Knott†*, Jennifer M. Jacobs†, Jo S. Daniel†, and Paul Kirshen‡ †Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering ‡School for the Environment University of New Hampshire University of Massachusetts Boston Durham, NH 03824, U.S.A. Boston, MA 02125, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Knott, J.F.; Jacobs, J.M.; Daniel, J.S., and Kirshen, P., 2019. Modeling groundwater rise caused by sea-level rise in coastal New Hampshire. Journal of Coastal Research, 35(1), 143–157. Coconut Creek (Florida), ISSN 0749-0208. Coastal communities with low topography are vulnerable from sea-level rise (SLR) caused by climate change and glacial isostasy. Coastal groundwater will rise with sea level, affecting water quality, the structural integrity of infrastructure, and natural ecosystem health. SLR-induced groundwater rise has been studied in coastal areas of high aquifer transmissivity. In this regional study, SLR-induced groundwater rise is investigated in a coastal area characterized by shallow unconsolidated deposits overlying fractured bedrock, typical of the glaciated NE. A numerical groundwater-flow model is used with groundwater observations and withdrawals, LIDAR topography, and surface-water hydrology to investigate SLR-induced changes in groundwater levels in New Hampshire’s coastal region. The SLR groundwater signal is detected more than three times farther inland than projected tidal flooding from SLR. The projected mean groundwater rise relative to SLR is 66% between 0 and 1 km, 34% between 1 and 2 km, 18% between 2 and 3 km, 7% between 3 and 4 km, and 3% between 4 and 5 km of the coastline, with large variability around the mean. -

Hydrographic Surveys Specifications and Deliverables

HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEYS SPECIFICATIONS AND DELIVERABLES March 2019 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Change Management ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Changes from April 2018 ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3.1 Hydrographer ................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3.2 Navigable Area Survey .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.4 Pre-Survey Assessment ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Environmental Compliance .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.6 Dangers to Navigation .......................................................................................................................................... -

Hydrographic Surveying Resources at ODOT

Hydrographic Surveying Resources @ ODOT David Moehl, PLS, CH Project Surveyor, ODOT Geometronics What is hydrography? • Hydrography is the measurement of physical features of a water body. • Bathymetry is the foundation of the science of hydrography. • Hydrography includes not only bathymetry, but also the shape and features of the shoreline; the characteristics of tides, currents, and waves; and the physical and chemical properties of the water itself. What is bathymetry? • The name is derived from Greek: • Bathus = Deep • and Meton = Measure • Dictionary: “The measurement of the depths of oceans, seas, or other large bodies of water, also: the data derived from such measurement.” • Wikipedia: “is the underwater equivalent to topography.” • NOAA: “The study of the ‘beds’ or ‘floors’ of water bodies, including the ocean, rivers, streams, and lakes and currently means ‘submarine topography’.” Source: https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov The lost city of Atlantis? Source: Google Earth How do we measure water depths? • Manual How do we measure water depths? • Manual How do we measure water depths? • Manual How do we measure water depths? • Manual • Sound • Echosounders • Determines the depth by measuring the two way travel time of sound through the water • Different types of echosounders Singlebeam echosounders • This is the tool that ODOT utilizes • Benefits of this system: • Most affordable and widely used • Less ongoing training, software and maintenance costs • Useful for: • Cross section data acquisition for hydraulic modeling • Uniform topography -

Geography, Hydrography and Climate 5

chapter 2 Geography, hydrography and climate 5 GEOGRAPHY 2.1 Introduction This chapter defines the principal geographical characteristics of the Greater North Sea. Its aim is to set the scene for the more detailed descriptions of the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the area and the impact man’s activities have had, and are having, upon them. For various reasons, certain areas (here called ‘focus areas’) have been given special attention. 6 Region II Greater North Sea 2.2 Definition of the region 2.3 Bottom topography The Greater North Sea, as defined in chapter one, is The bottom topography is important in relation to its effect situated on the continental shelf of north-west Europe. It on water circulation and vertical mixing. Flows tend to be opens into the Atlantic Ocean to the north and, via the concentrated in areas where slopes are steepest, with the Channel to the south-west, and into the Baltic Sea to the current flowing along the contours. The depth of the North east, and is divided into a number of loosely defined Sea (Figure 2.1) increases towards the Atlantic Ocean to areas. The open North Sea is often divided into the about 200 m at the edge of the continental shelf. The relatively shallow southern North Sea (including e.g. the Norwegian Trench, which has a sill depth (saddle point) of Southern Bight and the German Bight), the central North 270 m off the west coast of Norway and a maximum depth Sea, the northern North Sea, the Norwegian Trench and of 700 m in the Skagerrak, plays a major role in steering the Skagerrak. -

Tides and Water Level Requirements for N.O.S Hydrographic Surveys

International Hydrographic Review, Monaco, LXXVI(2), September 1999 TIDES AND WATER LEVEL REQUIREMENTS FOR N.O.S HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEYS by W. Michael G ib s o n and Stephen K. G i l l 1 Paper already presented at the HYDRO'99 Conference, Mobile, Alabama, USA, 27-29 April 1999. Abstract The Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS) of the National Ocean Service (NOS) contributes to the NOAA Nautical Charting Program by establishing requirements for, and providing the critical water level data necessary to produce accurate depth measurements. CO-OPS efforts involve six main functional areas: 1) tide and water level requirement planning; 2) preliminary tidal zoning development; 3) water level station installation, operation and removal; 4) data quality control, processing, and tabulation; 5) tidal datum computation and tidal datum recovery; and 6) generation of water level reducers and final tidal zoning. For each functional area, CO-OPS maintains appropriate specifications and standard operating procedures under the umbrella of an overall Data Quality Assurance Plan (DQAP). The objective of this effort is to provide the tide and water level correction information necessary to reduce soundings to Chart Datum. The goal is to provide water level correction information that meets current error budgets for correctors to soundings. The total uncertainty in the water level corrections are derived from three main sources: 1) errors in the actual measurement of water level; 2) uncertainties in the computation of tidal datums based on short period observations and in the datum recovery process at historical locations; and 3) uncertainties in the application of tidal zoning within the survey area. -

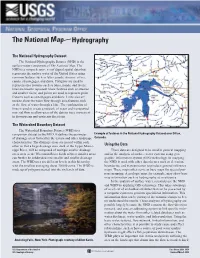

The National Map—Hydrography

The National Map—Hydrography The National Hydrography Dataset The National Hydrography Dataset (NHD) is the surface-water component of The National Map. The NHD is a comprehensive set of digital spatial data that represents the surface water of the United States using common features such as lakes, ponds, streams, rivers, canals, streamgages, and dams. Polygons are used to represent area features such as lakes, ponds, and rivers; lines are used to represent linear features such as streams and smaller rivers; and points are used to represent point features such as streamgages and dams. Lines also are used to show the water flow through area features such as the flow of water through a lake. The combination of lines is used to create a network of water and transported material flow to allow users of the data to trace movement in downstream and upstream directions. The Watershed Boundary Dataset The Watershed Boundary Dataset (WBD) is a companion dataset to the NHD. It defines the perimeter Example of features in the National Hydrography Dataset over Dillon, of drainage areas formed by the terrain and other landscape Colorado. characteristics. The drainage areas are nested within each Using the Data other so that a large drainage area, such as the Upper Missis- sippi River, will be composed of multiple smaller drainage These data are designed to be used in general mapping areas such as the Wisconsin River. Each of these smaller areas and in the analysis of surface-water systems using geo- can further be subdivided into smaller and smaller drainage graphic information system (GIS) technology. -

3 Hydrographic Positioning

HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEYS SPECIFICATIONS AND DELIVERABLES April 2017 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Change Management ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Changes from March 2016 .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3.1 Hydrographer ................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.3.2 Navigable Area Survey .................................................................................................................................. 6 1.4 Pre-Survey Assessment ......................................................................................................................................... 8 1.5 Environmental Compliance .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.6 Dangers to Navigation .......................................................................................................................................... -

Hydrography: Its Present State and Future Development

Hydrography: Its Present State and Future Development By Z. Kopacz, W. Morgas and J. Urbanski, Institute of Navigation and Hydrography, Naval University of Gdynia, Poland In this paper, considerations on the state ‘Seahydrographie’ in Germany; ‘hydro- of hydrography today and its development grafia morska’ in Poland, etc. trends are discussed and presented. The Hydrography, being the subject of our subject of hydrography and the objectives considerations, can be also considered of hydrographic activities are discussed. as a branch of marine science whose Also discussed are the reasons, as well means and methods can also be applied as the results, of changes, both those to the inland waterways, lakes, etc. that have been already accomplished and The subject of hydrography constitutes those that are now being accomplished. the measurement, description and This paper provides the authors’ opinion depiction of the water and coastal fea regarding the present state of hydrogra tures, but only these features, the phy and its future development trends. knowledge of which directly enhances the navigational safety as well as effi ciency of all human activities carried Introduction out in any kind of water environment. The following issues are presented Hydrography is generally considered as below: the definition of the ‘hydrogra the science, which deals with the fea phy’; the definition of hydrographic tures of the water as an element of the information; means, methods and geographical environment, i.e. the sci products of today’s hydrography; the ence as well as the human activity, impact of the computer, information which deals with the measurements, and space sciences and technologies description and depiction of these of hydrography and; the probable water features. -

Manual on Hydrography

INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC ORGANIZATION MANUAL ON HYDROGRAPHY Publication C-13 1st Edition May 2005 (Corrections to February 2011) PUBLISHED BY THE INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC BUREAU M O N A C O INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC ORGANIZATION MANUAL ON HYDROGRAPHY Publication C-13 1st Edition May 2005 (Corrections to February 2011) Published by the International Hydrographic Bureau 4, Quai Antoine 1er B.P. 445 - MC 98011 MONACO Cedex Principauté de Monaco Telefax: (377) 93 10 81 40 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.iho.int © Copyright International Hydrographic Organization [2010] This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted in accordance with the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886), and except in the circumstances described below, no part may be translated, reproduced by any process, adapted, communicated or commercially exploited without prior written permission from the International Hydrographic Bureau (IHB). Copyright in some of the material in this publication may be owned by another party and permission for the translation and/or reproduction of that material must be obtained from the owner. This document or partial material from this document may be translated, reproduced or distributed for general information, on no more than a cost recovery basis. Copies may not be sold or distributed for profit or gain without prior written agreement of the IHB and any other copyright holders. In the event that this document or partial material from this document is reproduced, translated or distributed under the terms described above, the following statements are to be included: “Material from IHO publication *reference to extract: Title, Edition] is reproduced with the permission of the International Hydrographic Bureau (IHB) (Permission No ……./…) acting for the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), which does not accept responsibility for the correctness of the material as reproduced: in case of doubt, the IHO’s authentic text shall prevail. -

The Risk of Sea Level Rise

THE RISK OF SEA LEVEL RISE:∗ A Delphic Monte Carlo Analysis in which Twenty Researchers Specify Subjective Probability Distributions for Model Coefficients within their Respective Areas of Expertise James G. Titus∗∗ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Vijay Narayanan Technical Resources International Abstract. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change requires nations to implement measures for adapting to rising sea level and other effects of changing climate. To decide upon an appropriate response, coastal planners and engineers must weigh the cost of these measures against the likely cost of failing to prepare, which depends on the probability of the sea rising a particular amount. This study estimates such a probability distribution, using models employed by previous assessments, as well as the subjective assessments of twenty climate and glaciology reviewers about the values of particular model coefficients. The reviewer assumptions imply a 50 percent chance that the average global temperature will rise 2°C degrees, as well as a 5 percent chance that temperatures will rise 4.7°C by 2100. The resulting impact of climate change on sea level has a 50 percent chance of exceeding 34 cm and a 1% chance of exceeding one meter by the year 2100, as well as a 3 percent chance of a 2 meter rise and a 1 percent chance of a 4 meter rise by the year 2200. The models and assumptions employed by this study suggest that greenhouse gases have contributed 0.5 mm/yr to sea level over the last century. Tidal gauges suggest that sea level is rising about 1.8 mm/yr worldwide, and 2.5-3.0 mm/yr along most of the U.S.