Creativity and the Experts: New Labour, Think Tanks and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yougov / the Sunday Times Survey Results

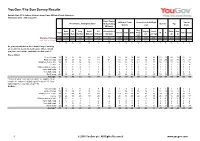

YouGov / The Sunday Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1011 Labour Party Members Fieldwork: 7th - 9th September 2010 1st Preference - September 2010 1st Preference - July 2010 September Choice July Choice Gender Age Diane Andy David Ed Diane Andy David Ed David Ed David Ed Total Ed Balls Ed Balls Male Female 18-34 35-54 55+ Abbott Burnham Miliband Miliband Abbott Burnham Miliband Miliband Miliband Miliband Miliband Miliband Weighted Sample 1008 106 86 91 354 287 99 45 65 244 209 431 474 320 340 577 432 331 303 374 Unweighted Sample 1011 102 89 97 344 296 93 45 69 239 221 429 485 310 353 654 357 307 317 387 % %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% 1st Preference - September 2010 [Excluding Don't know and Wouldn't Vote] David Miliband 38 0001000824 9 79 16 83 0 68 11 36 42 41 39 35 Ed Miliband 31 00001001114 13 11 69 1 62 11 50 31 31 33 28 33 Diane Abbott 11 1000000702 3144164181112131111 Andy Burnham 10 001000029 66 4 6 7 10 10 10 12 7 8 10 11 Ed Balls 9 0100000852 10 5 6 5 12 7 11 10 8 5 13 10 Weighted Sample 846 92 82 84 320 268 84 41 55 214 186 384 427 279 296 493 353 280 258 308 Unweighted Sample 849 90 85 89 308 277 80 41 58 207 199 380 438 268 309 555 294 260 266 323 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% 2nd Preference - September 2010 [Excluding Don't know and Wouldn't Vote] Ed Miliband 30 53 48 34 43 0 42 32 25 33 22 35 27 30 29 29 32 32 33 26 Ed Balls 22 200 2825251936 26 23 21 23 21 24 22 23 21 20 23 23 Andy Burnham 19 14 17 0 21 24 14 18 19 21 18 19 19 19 18 18 20 21 20 16 David Miliband 17 13 20 30 0 35 13 12 24 10 27 13 21 16 20 17 17 15 12 23 Diane Abbott 11 0 15 8 11 16 11 2 7 12 12 9 12 11 11 12 10 12 11 12 Weighted Sample 905 90 74 75 351 285 82 40 56 233 203 431 474 299 319 519 387 303 267 336 Unweighted Sample 914 87 78 84 341 293 79 40 60 228 214 429 485 290 334 592 322 283 280 351 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% Miliband preference - September [Excluding definitely wouldn't vote] David Miliband 48 19 28 41 100 1 25 34 37 86 17 100 0 80 17 47 49 48 46 48 Ed Miliband 52 81 72 59 0 99 75 66 63 14 83 0 100 20 83 53 51 52 54 52 1 © 2010 YouGov plc. -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

UK Border Agency

UK Border Agency Title Instructions on drafting replies to MPs’ Correspondence Process Drafting of letters to enquiries from MPs’ and their offices 26 30 November Implementation Date November Expiry/Review Date 2009 2008 CONTAINS MANDATORY INSTRUCTIONS For Action Author All Ministerial drafting units within the UK Border Agency For Information Owner To all units in the UK Border Agency Jill Beckingham handling correspondence. Contact Point Processes Affected All processes relating to answering correspondence from Members of Parliament Assumptions Drafters have sufficient knowledge of their subject to accurately answer the questions raised by a Member of Parliament. NOTES 26 November Issued 2008 Version 3.1 Chapter 1 – General Advice on Correspondence Basics of Writing a Letter Letter Structure Addressing the Letter Opening Paragraph Middle Paragraphs Sign-off Enclosures Background Notes Parliamentary Conventions More than one MP has written about the same person Interim replies Requests from MPs for meetings Chapter 2 – Advice on Ministerial Correspondence Signing of Ministerial Letters Drafting for Ministers Annex 2.A – Phil Woolas Template Annex 2.B – Meg Hillier Template Annex 2.C – Home Secretary Template Annex 2.D – Chief Executive Template Annex 2.E – Home Secretary Stop List Chapter 3 – Advice on Official Replies Use of Official Reply Template Drafting Official Replies Signing Official Replies Annex 3.A – Official Reply Template Chapter 4 – Third Party Replies What is a third party? MPs acting on behalf of a relative of an applicant -

Tory Modernisation 2.0 Tory Modernisation

Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg Guy and Shorthouse Ryan by Edited TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 MODERNISATION TORY edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 THE FUTURE OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 The future of the Conservative Party Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a re- trieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent, not-for-profit organisation which cam- paigns for the Conservative Party to implement liberal and progressive policies that draw on Conservative traditions of community, entre- preneurialism, responsibility, liberty and fairness. First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Bright Blue Campaign www.brightblue.org.uk ISBN: 978-1-911128-00-7 Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2013 Printed and bound by DG3 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Contents Acknowledgements 1 Foreword 2 Rt Hon Francis Maude MP Introduction 5 Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg 1 Last chance saloon 12 The history and future of Tory modernisation Matthew d’Ancona 2 Beyond bare-earth Conservatism 25 The future of the British economy Rt Hon David Willetts MP 3 What’s wrong with the Tory party? 36 And why hasn’t -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

Better Protecting BBC Financial Independence an Exploratory Report for the BBC Trust

Better protecting BBC financial independence An exploratory report for the BBC Trust Martin Moore King’s College London January 2016 The Policy Institute at King’s About the Policy Institute at King’s The Policy Institute at King’s College London acts as a hub, linking insightful research with rapid, relevant policy analysis to stimulate debate, inform and shape future policy agendas. Building on King’s central London location at the heart of the global policy conversation, our vision is to enable the translation of academic research into policy and practice by facilitating engagement between academic, business and policy communities around current and future policy needs. We combine the academic excellence of King’s with connectedness of a think tank and the professionalism of a consultancy. Moore, M., Better protecting BBC financial independence: an exploratory report for the BBC Trust, Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power, the Policy Institute at King’s College London, January 2016. About the author Martin Moore Dr Martin Moore is a Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power at the Policy Institute at King’s College London. He has twenty years experience working across the UK media, in the commercial sector, the third sector and in academia. 1 Preface This report was commissioned by the BBC Trust in order to explore ways to better protect the BBC’s financial independence beyond Charter Renewal. The ideas presented in the report are derived from ten interviews with expert sources conducted for the study in October and November 2015, supplemented by relevant publicly available information. -

Survey Report

R YouGov/ Sunday Times Survey Results YouGov Sample Size: 1755 Fieldwork: 10th - 11th April 2008 For detailed results, click here % Headline Voting Intention [Excluding Don't Knows and Wouldn't Votes] Con 44 Lab 28 Lib Dem 17 Other 11 Do you think Gordon Brown is doing well or badly as prime minister? Very well 2 Fairly well 26 Fairly badly 37 Very badly 28 Don’t know 7 Do you think David Cameron is doing well or badly as Conservative leader? Very well 7 Fairly well 44 Fairly badly 27 Very badly 11 Don’t know 11 Do you think Nick Clegg is doing well or badly as leader of the Liberal Democrats? Very well 1 Fairly well 25 Fairly badly 24 Very badly 11 Don’t know 38 Do you think house prices in your area will rise or fall over the next 12 months? Rise by more than 10% 2 Rise by less than 10% 10 TOTAL RISE 12 Stay about the same 28 Fall by less than 10% 41 Fall by more than 10% 13 TOTAL FALL 54 Don’t know 6 Over the next 12 months do you think Britain's economy will... Grow at a faster rate than over the past 12 months 1 Grow at about the same rate 5 Grow more slowly 35 Not grow at all 28 Go into recession 26 Don't know 6 1 © 2008 YouGov plc. All Rights Reserved www.yougov.com R % YouGov How much do you trust Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling to lead Britain through the present financial crisis? Trust a lot 4 Trust to some extent 25 Do not trust much 30 Do not trust at all 36 Don’t know 6 Thinking about Prime Minister Gordon Brown which of the following qualities do you think he has? [Please tick all that apply.] Sticks to what he believes -

Survey Report

YouGov /The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 1102 Labour Voting Labour Party Affiliated Trade Unionists Fieldwork: 27th - 29th July 2010 First Choice Affiliated Trade Yourself on Left-Right Social First Choice Voting Intention VI Excluding Gender Age Unions scale Grade Mililands Very/ Diane Ed Andy David Ed Abbott, Balls & Slightly Centre Under Over Total Unison Unite GMB Fairly M F ABC1 C2DE Abbott Balls Burnham Miliband Miliband Burnham Left and Right 40 40 Left Weighted Sample 1094 148 100 116 301 230 364 357 346 166 455 347 171 654 440 279 815 621 473 Unweighted Sample 1102 150 100 116 309 232 366 481 305 122 467 354 171 703 399 276 826 635 467 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % As you probably know, the Labour Party is holding an election to decide its next leader. Where would you place each of the candidates on this scale?* Diane Abbott Very left-wing 17 12 15 26 20 23 17 16 19 18 22 20 12 21 13 21 16 21 13 Fairly left-wing 32 50 28 42 32 34 41 33 35 31 40 42 16 34 29 22 36 36 27 Slightly left-of-centre 14 20 18 14 14 14 17 14 15 15 17 17 11 16 12 12 15 13 15 Centre 5 5 6 3 5 7 5 5 4 8 5 4 9 5 5 7 5 6 4 Slightly right-of-centre 4 1 7 2 4 4 3 3 3 5 4 2 8 3 4 3 4 4 3 Fairly right-wing 1 1 0 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 0 2 1 1 Very right-wing 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 Don't know 26 12 26 11 24 14 15 27 22 22 12 14 39 19 36 34 23 19 34 Average* -56 -57 -49 -62 -56 -57 -56 -57 -57 -53 -59 -61 -32 -57 -54 -60 -54 -59 -55 * Very left-wing=-100; fairly left-wing=-67; slightly left-of- centre=-33; centre=0; slightly right-of-centre=+33; -

Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing

Notes Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing 2 Stanley Kelley, Professional Public Relations and Political Power (1956) p. 210. 2 Hugo Young and Anne Sloman, The Thatcher Phenomenon (1986) p. 94. 3 Ibid., pp. 94-5. 4 See especially New Statesman's election edition, 10 June 1983. 5 For an account of the programme, see The Listmer, 16 June 1983. 6 Wendy Webster, Not A Man To Matcll Her (1990). 7 Philip Kleinman, The Saatchi & Saatchi Story (1987) p. 32. 8 Campaign, 30 November 1990. 9 Martin Harrop, 'Political Marketing', in ParliamentaryAffairs,July 1990, 43(3). 10 Interview with Peter Mandelson at the Labour Party conference, Black- pool, October 1986. 11 'Party Presence', in Marxism Today, October 1989. 12 Harrop, op. cit. 13 The £11 million figure is quoted in Eric Clark, The Want Makers (1988) p. 312. For a full account of the GLC campaign and its success in shifting public opinion, see Robert Waller, Moulding Political Opinion (1988). 14 Obse1ver, 24 December 1989. 15 Richard Rose, Influencing Voters (1967) p. 13. 16 See Michael Cockerell, Live from Number 10, pp. 280-1. 17 Quoted in HJ. Hanham, Ekctions and Party Management: Politics in the Time of Disraeli and Gladstone ( 1978) p. 202. 18 Serge Chakotin, The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Propaganda (1939) pp. 131-3. 19 Ibid., p. 171. 20 Ibid. 21 See Max Atkinson, Our Masters' Voices (1988) pp. 13-14. 22 Quoted in Michael Thomas, The Economist Guide to Marketing (1986). 23 Michael J. Baker, 'One More Time- What is Marketing?', in Michael J. -

The Crisis of the Democratic Left in Europe

The crisis of the democratic left in Europe Denis MacShane Published by Progress 83Victoria Street, London SW1H 0HW Tel: 020 3008 8180 Fax: 020 3008 8181 Email: [email protected] www.progressonline.org.uk Progress is an organisation of Labour party members which aims to promote a radical and progressive politics for the 21st century. We seek to discuss, develop and advance the means to create a more free, equal and democratic Britain, which plays an active role in Europe and the wider the world. Diverse and inclusive, we work to improve the level and quality of debate both within the Labour party, and between the party and the wider progressive communnity. Honorary President : Rt Hon Alan Milburn MP Chair : StephenTwigg Vice chairs : Rt Hon Andy Burnham MP, Chris Leslie, Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP, Baroness Delyth Morgan, Meg Munn MP Patrons : Rt Hon Douglas Alexander MP, Wendy Alexander MSP, Ian Austin MP, Rt Hon Hazel Blears MP, Rt HonYvette Cooper MP, Rt Hon John Denham MP, Parmjit Dhanda MP, Natascha Engel MP, Lorna Fitzsimons, Rt Hon Peter Hain MP, John Healey MP, Rt Hon Margaret Hodge MP, Rt Hon Beverley Hughes MP, Rt Hon John Hutton MP, Baroness Jones, Glenys Kinnock MEP, Sadiq Kahn MP, Oona King, David Lammy MP, Cllr Richard Leese,Rt Hon Peter Mandelson, Pat McFadden MP, Rt Hon David Miliband MP,Trevor Phillips, Baroness Prosser, Rt Hon James Purnell MP, Jane Roberts, LordTriesman. Kitty Ussher MP, Martin Winter Honorary Treasurer : Baroness Margaret Jay Director : Robert Philpot Deputy Director : Jessica Asato Website and Communications Manager :Tom Brooks Pollock Events and Membership Officer : Mark Harrison Publications and Events Assistant : EdThornton Published by Progress 83 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0HW Tel: 020 3008 8180 Fax: 020 3008 8181 Email: [email protected] www.progressives.org.uk 1 .